Companion volume

COMMON EUROPEAN

FRAMEWORK

OF REFERENCE

FOR LANGUAGES:

LEARNING, TEACHING,

ASSESSMENT

The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading

human rights organisation. It comprises 47 member

stat

es, including all members of the European Union.

All Council of Europe member states have signed

up to the European Convention on Human Rights,

a treaty designed to protect human rights, democracy

and the rule of la

w. The European Court of Human Rights

oversees the implementation of the Convention in

the member states.

The CEFR Companion volume broadens the scope of language education. It re-

ects academic and societal developments since the publication of the Common

European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and updates the 2001

version. It owes much to the contributions of members of the language teaching

profession across Europe and beyond.

This volume contains:

► an explanation of the key aspects of the CEFR for teaching and learning;

►

a complete set of updated CEFR descriptors that replaces the 2001 set with:

- modality-inclusive and gender-neutral descriptors;

- added detail on listening and reading;

- a new Pre–A1 level, plus enriched description at A1 and C levels;

- a replacement scale for phonological competence;

- new scales for mediation, online interaction and plurilingual/

pluricultural competence;

- new scales for sign language competence;

► a short report on the four-year development, validation and consultation

processes.

The CEFR Companion volume represents another step in a process of engage-

ment with language education that has been pursued by the Council of Europe

since 1971 and which seeks to:

► promote and support the learning and teaching of modern languages;

►

enhance intercultural dialogue, and thus mutual understanding, social

cohesion and democracy;

► protect linguistic and cultural diversity in Europe; and

► promote the right to quality education for all.

ENG

PREMS 058220

http://book.coe.int

ISBN 978-92-871-8621-8

€29/US$58

EDUCATION FOR DEMOCRACY

COMMON EUROPEAN FRAMEWORK OF REFERENCE FOR LANGUAGES: LEARNING, TEACHING, ASSESSMENT

www.coe.int/lang-cefr

9 789287 186218

French edition:

Cadre européen commun de référence

pour les langues : apprendre, enseigner,

évaluer – Volume complémentaire

All rights reserved. No part of this

publication may be translated, reproduced

or transmitted, in any form or by any

means, electronic (CD-Rom, internet, etc.)

or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording or any information storage or

retrieval system, without prior permission

in writing from the Directorate of

Communication (F-67075 Strasbourg

Cedex or publishing@coe.int).

Cover design and layout: Documents

and Publications Production Department

(SPDP), Council of Europe

ISBN 978-92-871-8621-8

© Council of Europe, April 2020

Printed at the Council of Europe

Citation reference: Council of Europe

(2020), Common European Framework

of Reference for Languages: Learning,

teaching, assessment – Companion volume,

Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg,

available at www.coe.int/lang-cefr.

A preliminary version of this update to the Common European Framework

of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment was published

online in English and French in 2018 as “Common European Framework

of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment: Companion

Volume with New Descriptors” and “Cadre européen commun de référence

pour les langues: apprendre, enseigner, évaluer : Volume complémentaire

avec de nouveaux descripteurs”, respectively.

This volume presents the key messages of the CEFR in a user-friendly

form and contains all CEFR illustrative descriptors. For pedagogical use

of the CEFR for learning, teaching and assessment, teachers and teacher

educators will nd it easier to access the CEFR Companion volume as

the updated framework. The Companion volume provides the links and

references to also consult the chapters of the 2001 edition, where necessary.

Researchers wishing to interrogate the underlying concepts and guidance

in CEFR chapters about specic areas should access the 2001 edition,

which remains valid.

Page 5

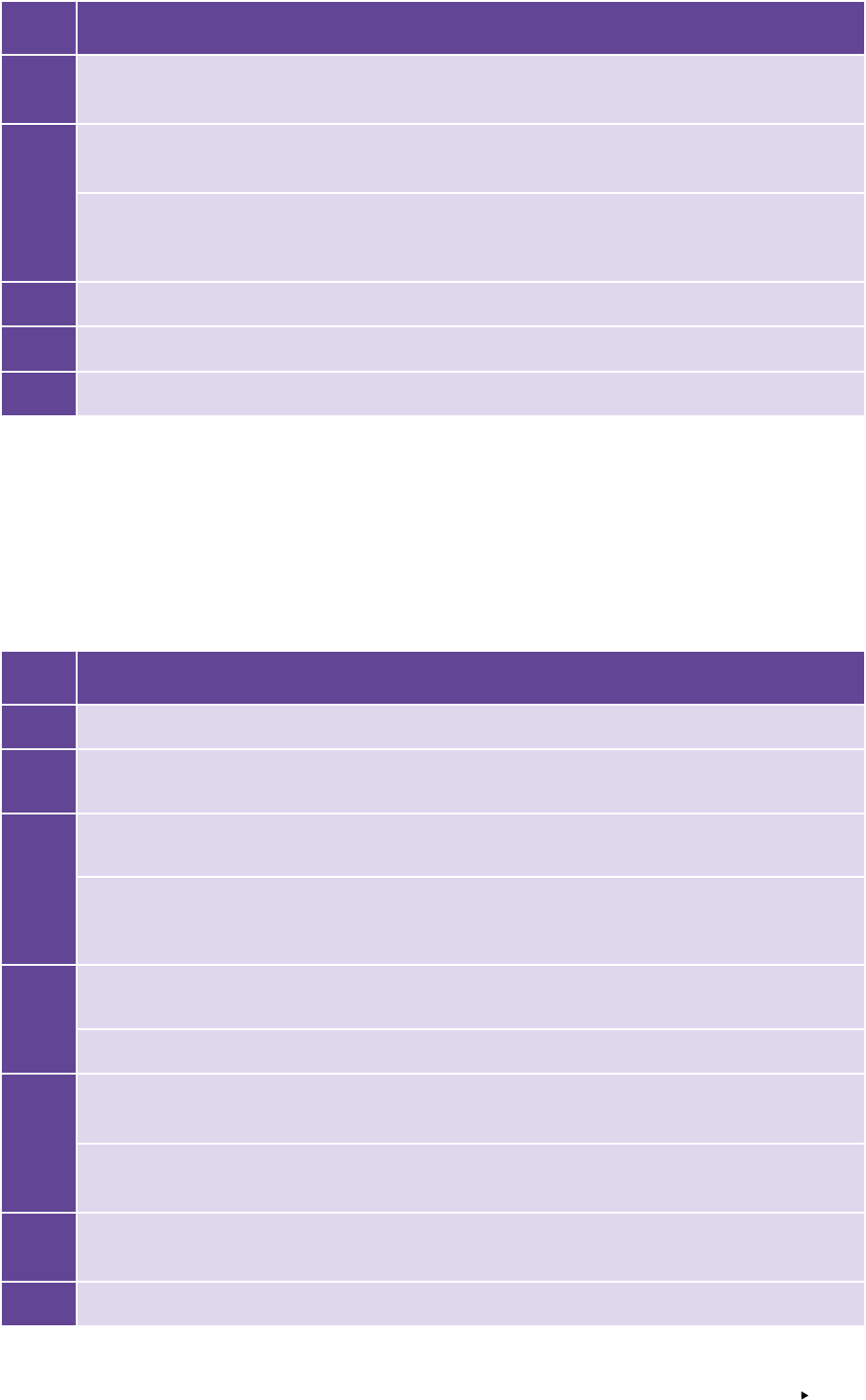

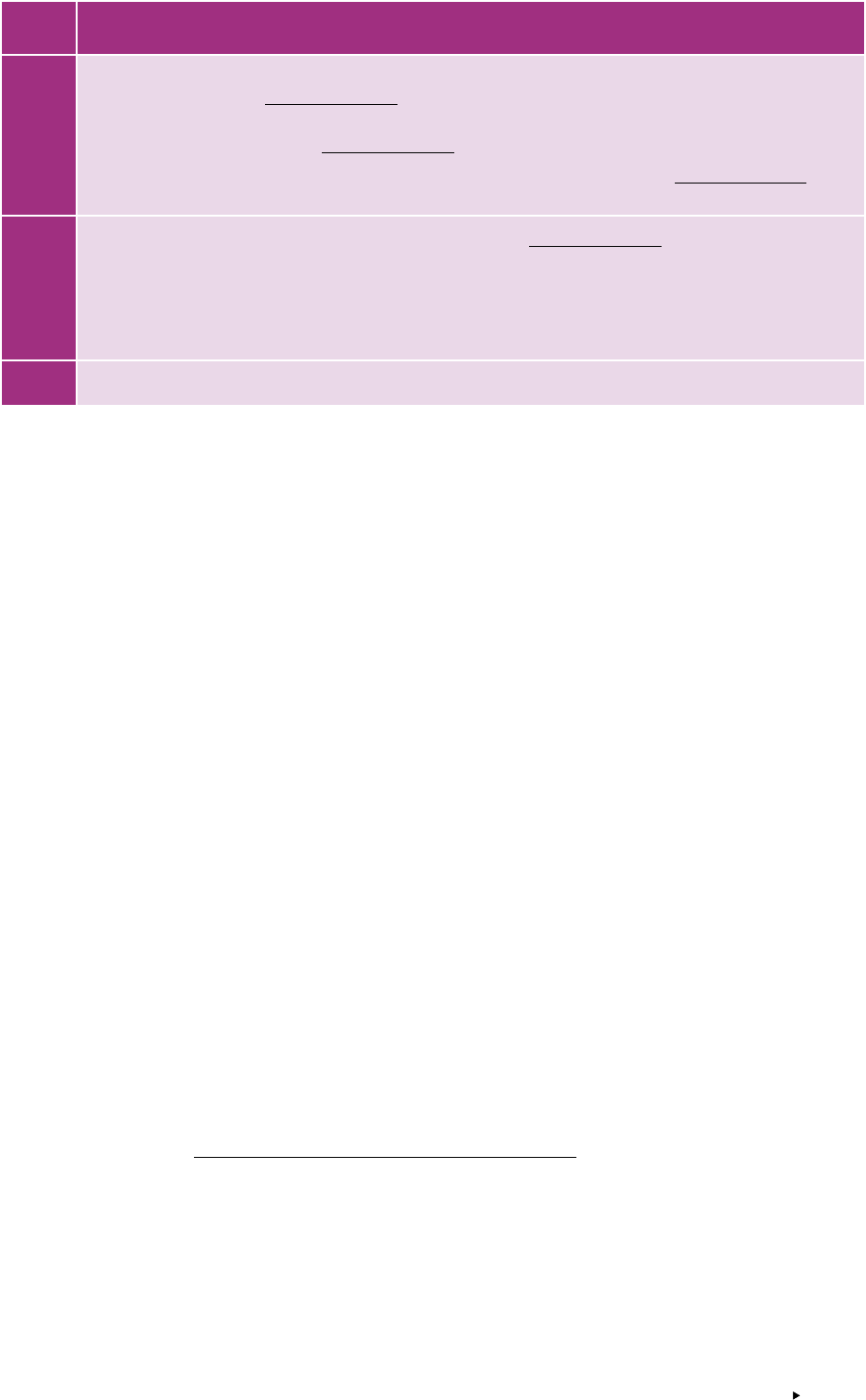

CONTENTS

FOREWORD 11

PREFACE WITH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 13

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 21

1.1. SUMMARY OF CHANGES TO THE ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTORS 24

CHAPTER 2: KEY ASPECTS OF THE CEFR FOR TEACHING AND LEARNING 27

2.1. AIMS OF THE CEFR 28

2.2. IMPLEMENTING THE ACTIONORIENTED APPROACH 29

2.3. PLURILINGUAL AND PLURICULTURAL COMPETENCE 30

2.4. THE CEFR DESCRIPTIVE SCHEME 31

2.5. MEDIATION 35

2.6. THE CEFR COMMON REFERENCE LEVELS 36

2.7. CEFR PROFILES 38

2.8. THE CEFR ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTORS 41

2.9. USING THE CEFR ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTORS 42

2.10. SOME USEFUL RESOURCES FOR CEFR IMPLEMENTATION 44

2.10.1. WEB RESOURCES 44

2.10.2. BOOKS 45

CHAPTER 3: THE CEFR ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTOR SCALES:

COMMUNICATIVE LANGUAGE ACTIVITIES AND STRATEGIES 47

3.1. RECEPTION 47

3.1.1. RECEPTION ACTIVITIES 48

3.1.1.1. ORAL COMPREHENSION 48

OVERALL ORAL COMPREHENSION 48

UNDERSTANDING CONVERSATION BETWEEN OTHER PEOPLE 49

UNDERSTANDING AS A MEMBER OF A LIVE AUDIENCE 50

UNDERSTANDING ANNOUNCEMENTS AND INSTRUCTIONS 51

UNDERSTANDING AUDIO OR SIGNED MEDIA AND RECORDINGS 52

3.1.1.2. AUDIOVISUAL COMPREHENSION 52

WATCHING TV, FILM AND VIDEO 52

3.1.1.3. READING COMPREHENSION 53

OVERALL READING COMPREHENSION 54

READING CORRESPONDENCE 54

Page 6 3 CEFR – Companion volume

READING FOR ORIENTATION 55

READING FOR INFORMATION AND ARGUMENT 56

READING INSTRUCTIONS 58

READING AS A LEISURE ACTIVITY 58

3.1.2. RECEPTION STRATEGIES 59

IDENTIFYING CUES AND INFERRING SPOKEN, SIGNED AND WRITTEN 60

3.2. PRODUCTION 60

3.2.1. PRODUCTION ACTIVITIES 61

3.2.1.1. ORAL PRODUCTION 61

OVERALL ORAL PRODUCTION 62

SUSTAINED MONOLOGUE: DESCRIBING EXPERIENCE 62

SUSTAINED MONOLOGUE: GIVING INFORMATION 63

SUSTAINED MONOLOGUE: PUTTING A CASE E.G. IN A DEBATE 64

PUBLIC ANNOUNCEMENTS 64

ADDRESSING AUDIENCES 65

3.2.1.2. WRITTEN PRODUCTION 66

OVERALL WRITTEN PRODUCTION 66

CREATIVE WRITING 67

REPORTS AND ESSAYS 68

3.2.2. PRODUCTION STRATEGIES 68

PLANNING 69

COMPENSATING 69

MONITORING AND REPAIR 70

3.3. INTERACTION 70

3.3.1. INTERACTION ACTIVITIES 71

3.3.1.1. ORAL INTERACTION 71

OVERALL ORAL INTERACTION 72

UNDERSTANDING AN INTERLOCUTOR 72

CONVERSATION 73

INFORMAL DISCUSSION WITH FRIENDS 74

FORMAL DISCUSSION MEETINGS 75

GOALORIENTED COOPERATION 76

OBTAINING GOODS AND SERVICES 77

INFORMATION EXCHANGE 78

INTERVIEWING AND BEING INTERVIEWED 80

USING TELECOMMUNICATIONS 81

3.3.1.2. WRITTEN INTERACTION 81

OVERALL WRITTEN INTERACTION 82

CORRESPONDENCE 82

NOTES, MESSAGES AND FORMS 83

3.3.1.3. ONLINE INTERACTION 84

ONLINE CONVERSATION AND DISCUSSION 84

Page 7

GOALORIENTED ONLINE TRANSACTIONS AND COLLABORATION 86

3.3.2. INTERACTION STRATEGIES 87

TURNTAKING 88

COOPERATING 88

ASKING FOR CLARIFICATION 89

3.4. MEDIATION 90

3.4.1. MEDIATION ACTIVITIES 91

OVERALL MEDIATION 91

3.4.1.1. MEDIATING A TEXT 92

RELAYING SPECIFIC INFORMATION 93

EXPLAINING DATA 96

PROCESSING TEXT 98

TRANSLATING A WRITTEN TEXT 102

NOTETAKING LECTURES, SEMINARS, MEETINGS, ETC. 105

EXPRESSING A PERSONAL RESPONSE TO CREATIVE TEXTS INCLUDING LITERATURE 106

ANALYSIS AND CRITICISM OF CREATIVE TEXTS INCLUDING LITERATURE 107

3.4.1.2. MEDIATING CONCEPTS 108

FACILITATING COLLABORATIVE INTERACTION WITH PEERS 109

COLLABORATING TO CONSTRUCT MEANING 109

MANAGING INTERACTION 112

ENCOURAGING CONCEPTUAL TALK 112

3.4.1.3. MEDIATING COMMUNICATION 114

FACILITATING PLURICULTURAL SPACE 114

ACTING AS AN INTERMEDIARY IN INFORMAL SITUATIONS WITH FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES 115

FACILITATING COMMUNICATION IN DELICATE SITUATIONS AND DISAGREEMENTS 116

3.4.2. MEDIATION STRATEGIES 117

3.4.2.1. STRATEGIES TO EXPLAIN A NEW CONCEPT 118

LINKING TO PREVIOUS KNOWLEDGE 118

ADAPTING LANGUAGE 118

BREAKING DOWN COMPLICATED INFORMATION 118

3.4.2.2. STRATEGIES TO SIMPLIFY A TEXT 121

AMPLIFYING A DENSE TEXT 121

STREAMLINING A TEXT 121

CHAPTER 4: THE CEFR ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTOR SCALES:

PLURILINGUAL AND PLURICULTURAL COMPETENCE 123

BUILDING ON PLURICULTURAL REPERTOIRE 124

PLURILINGUAL COMPREHENSION 126

BUILDING ON PLURILINGUAL REPERTOIRE 127

CHAPTER 5: THE CEFR ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTOR SCALES:

COMMUNICATIVE LANGUAGE COMPETENCES 129

5.1. LINGUISTIC COMPETENCE 130

GENERAL LINGUISTIC RANGE 130

Page 8 3 CEFR – Companion volume

VOCABULARY RANGE 131

GRAMMATICAL ACCURACY 132

VOCABULARY CONTROL 132

PHONOLOGICAL CONTROL 133

ORTHOGRAPHIC CONTROL 136

5.2. SOCIOLINGUISTIC COMPETENCE 136

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPROPRIATENESS 136

5.3. PRAGMATIC COMPETENCE 137

FLEXIBILITY 138

TURNTAKING 139

THEMATIC DEVELOPMENT 139

COHERENCE AND COHESION 140

PROPOSITIONAL PRECISION 141

FLUENCY 142

CHAPTER 6: THE CEFR ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTOR SCALES: SIGNING COMPETENCES 143

6.1. LINGUISTIC COMPETENCE 144

SIGN LANGUAGE REPERTOIRE 144

DIAGRAMMATICAL ACCURACY 149

6.2. SOCIOLINGUISTIC COMPETENCE 153

SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPROPRIATENESS AND CULTURAL REPERTOIRE 153

6.3. PRAGMATIC COMPETENCE 157

SIGN TEXT STRUCTURE 157

SETTING AND PERSPECTIVES 161

LANGUAGE AWARENESS AND INTERPRETATION 164

PRESENCE AND EFFECT 166

PROCESSING SPEED 167

SIGNING FLUENCY 168

APPENDICES 171

APPENDIX 1: SALIENT FEATURES OF THE CEFR LEVELS 173

APPENDIX 2: SELFASSESSMENT GRID

EXPANDED WITH ONLINE INTERACTION AND MEDIATION 177

APPENDIX 3: QUALITATIVE FEATURES OF SPOKEN LANGUAGE EXPANDED WITH PHONOLOGY 183

APPENDIX 4: WRITTEN ASSESSMENT GRID 187

APPENDIX 5: EXAMPLES OF USE IN DIFFERENT DOMAINS FOR DESCRIPTORS OF ONLINE

INTERACTION AND MEDIATION ACTIVITIES 191

APPENDIX 6: DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE EXTENDED ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTORS 243

APPENDIX 7: SUBSTANTIVE CHANGES TO SPECIFIC DESCRIPTORS PUBLISHED IN 2001 257

APPENDIX 8: SUPPLEMENTARY DESCRIPTORS 259

APPENDIX 9: SOURCES FOR NEW DESCRIPTORS 269

APPENDIX 10: ONLINE RESOURCES 273

Page 9

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

LIST OF FIGURES

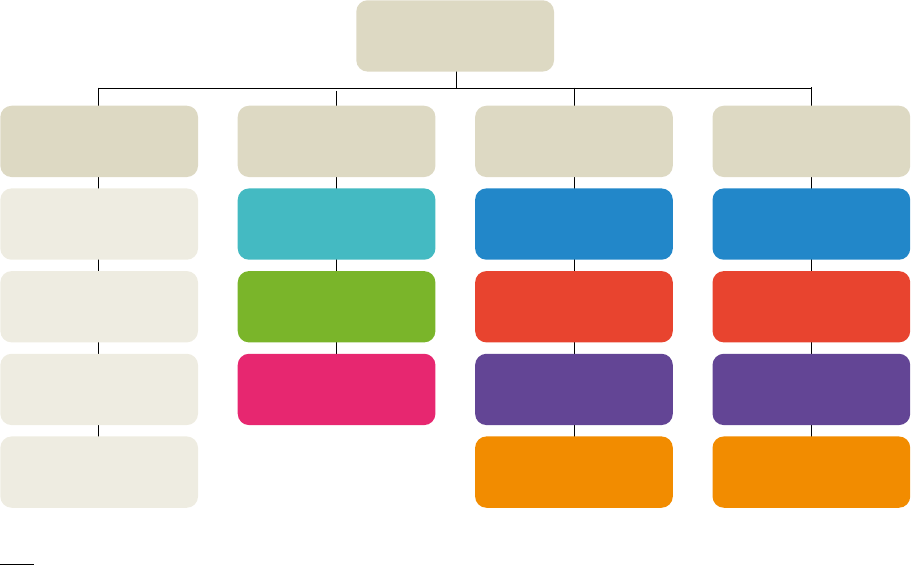

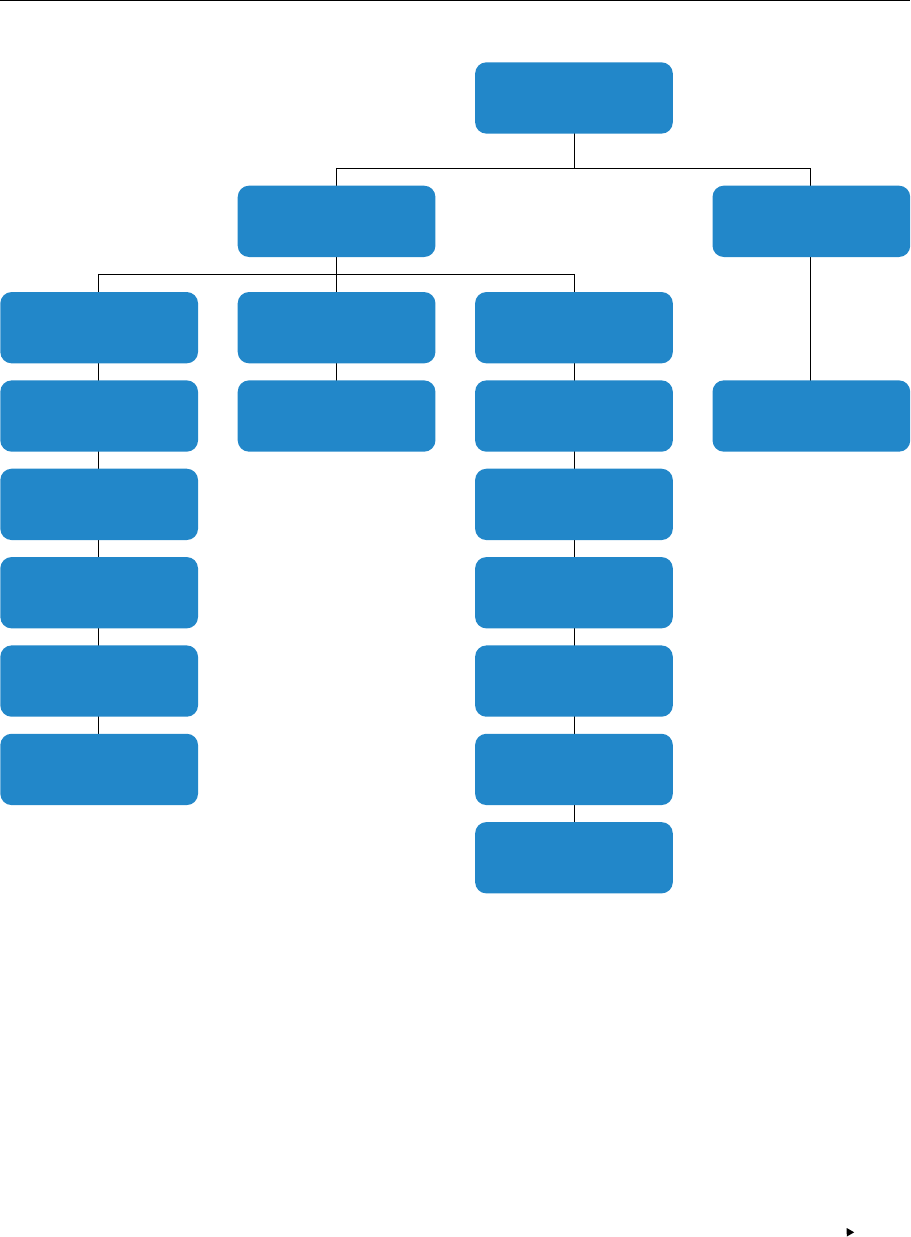

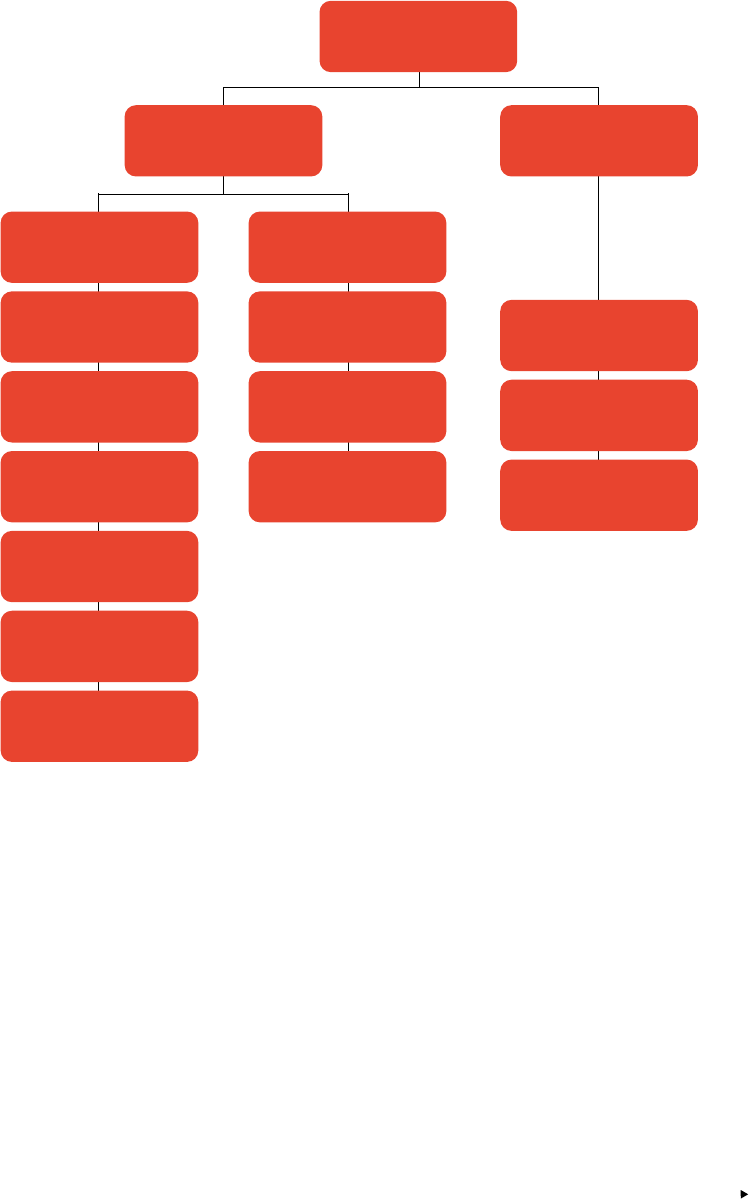

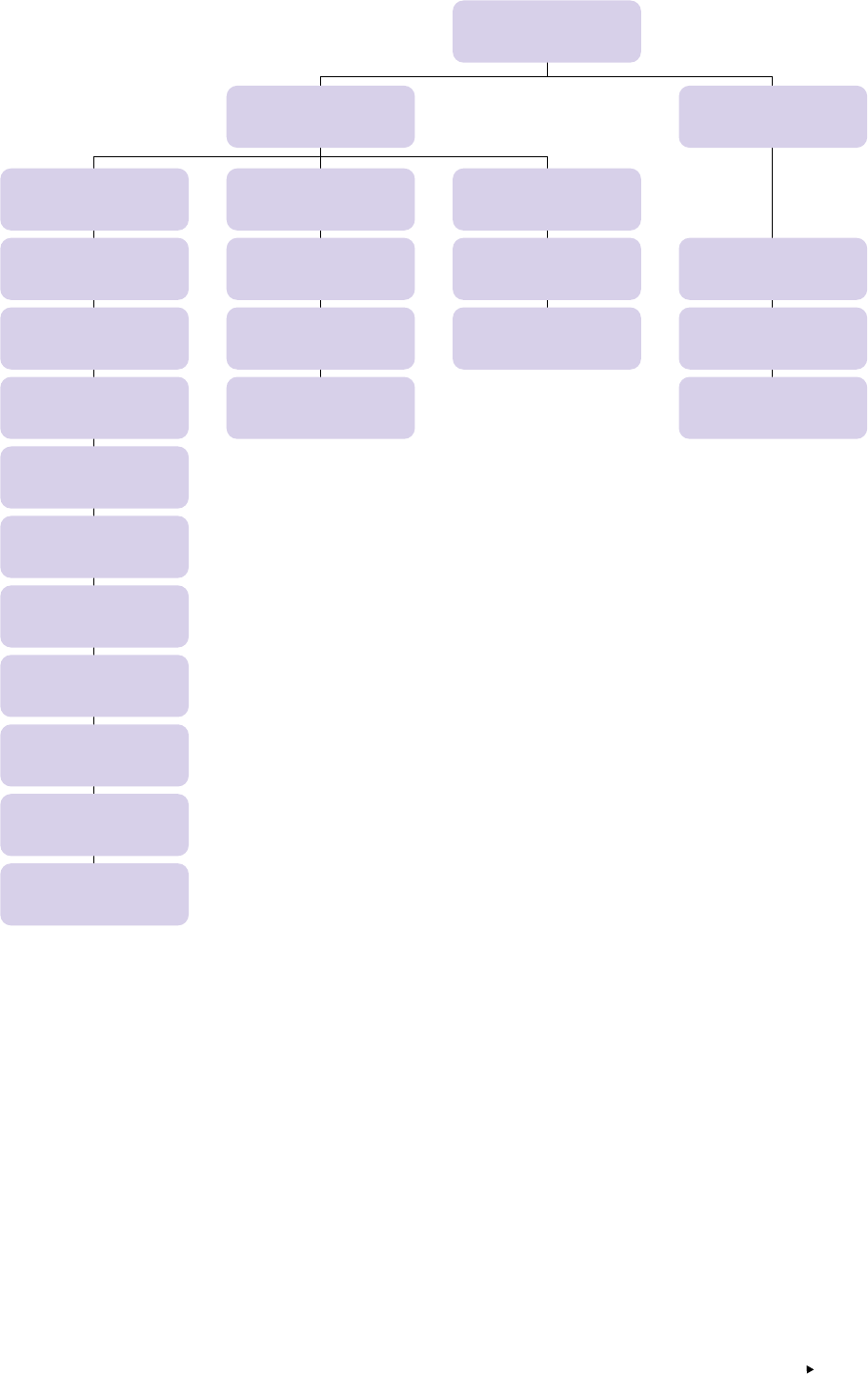

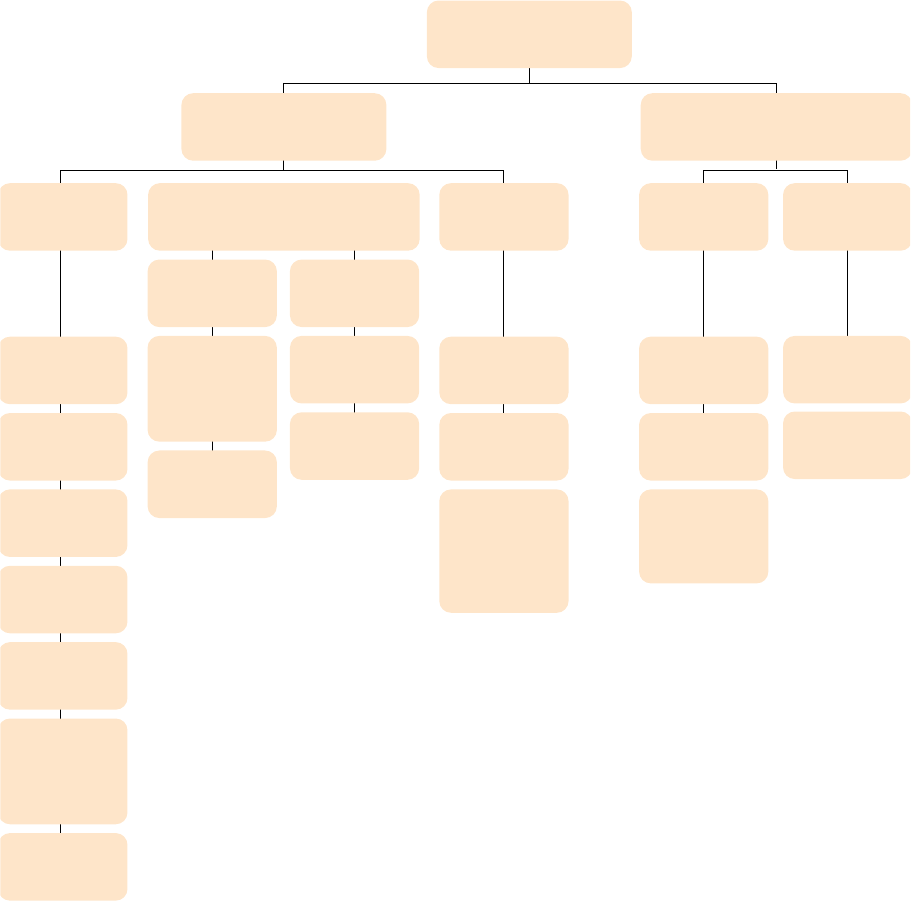

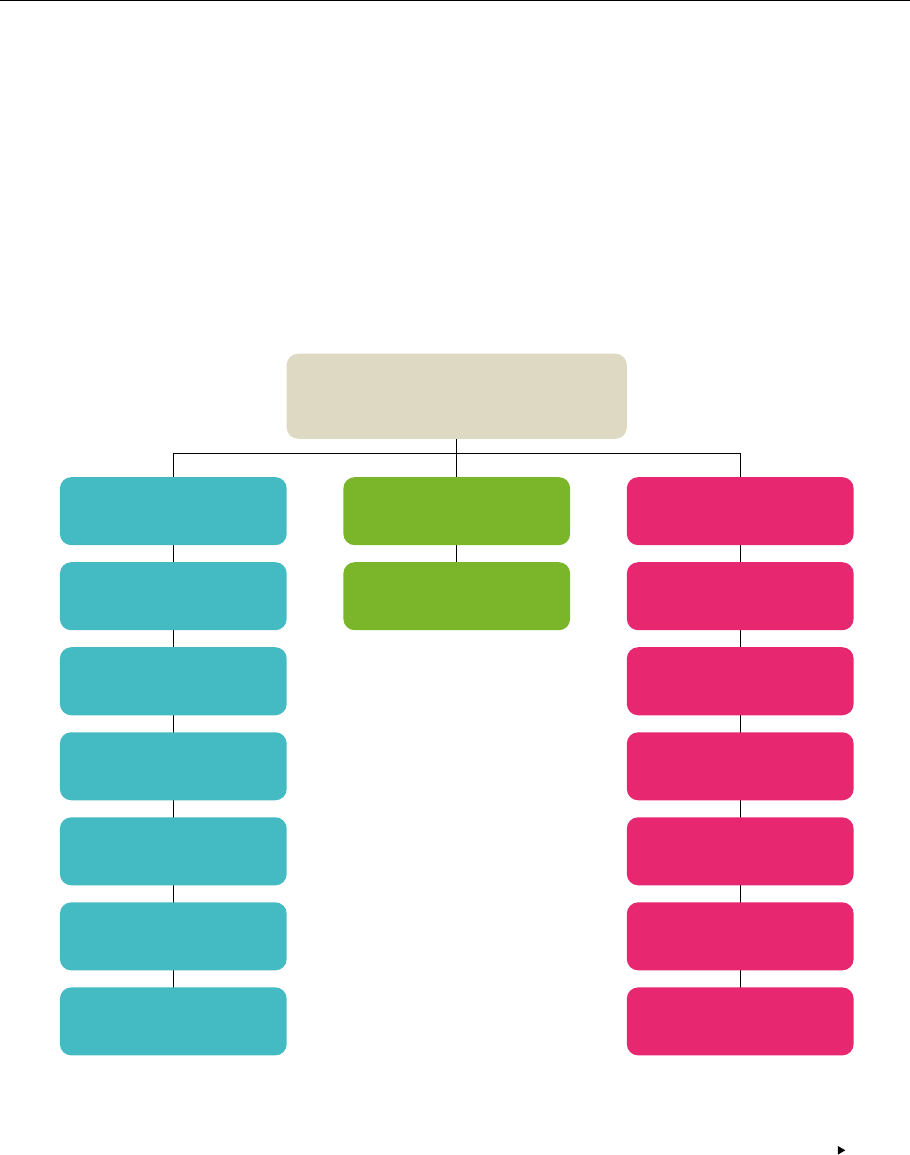

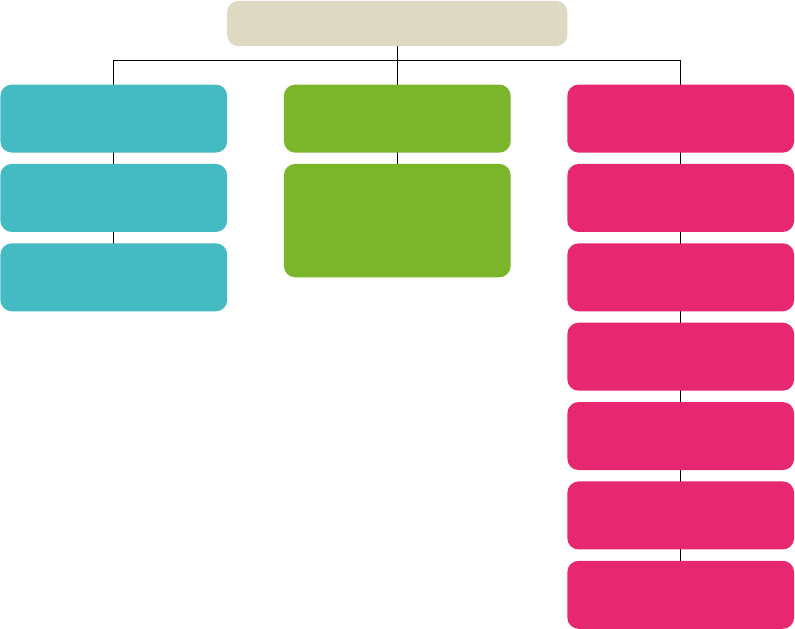

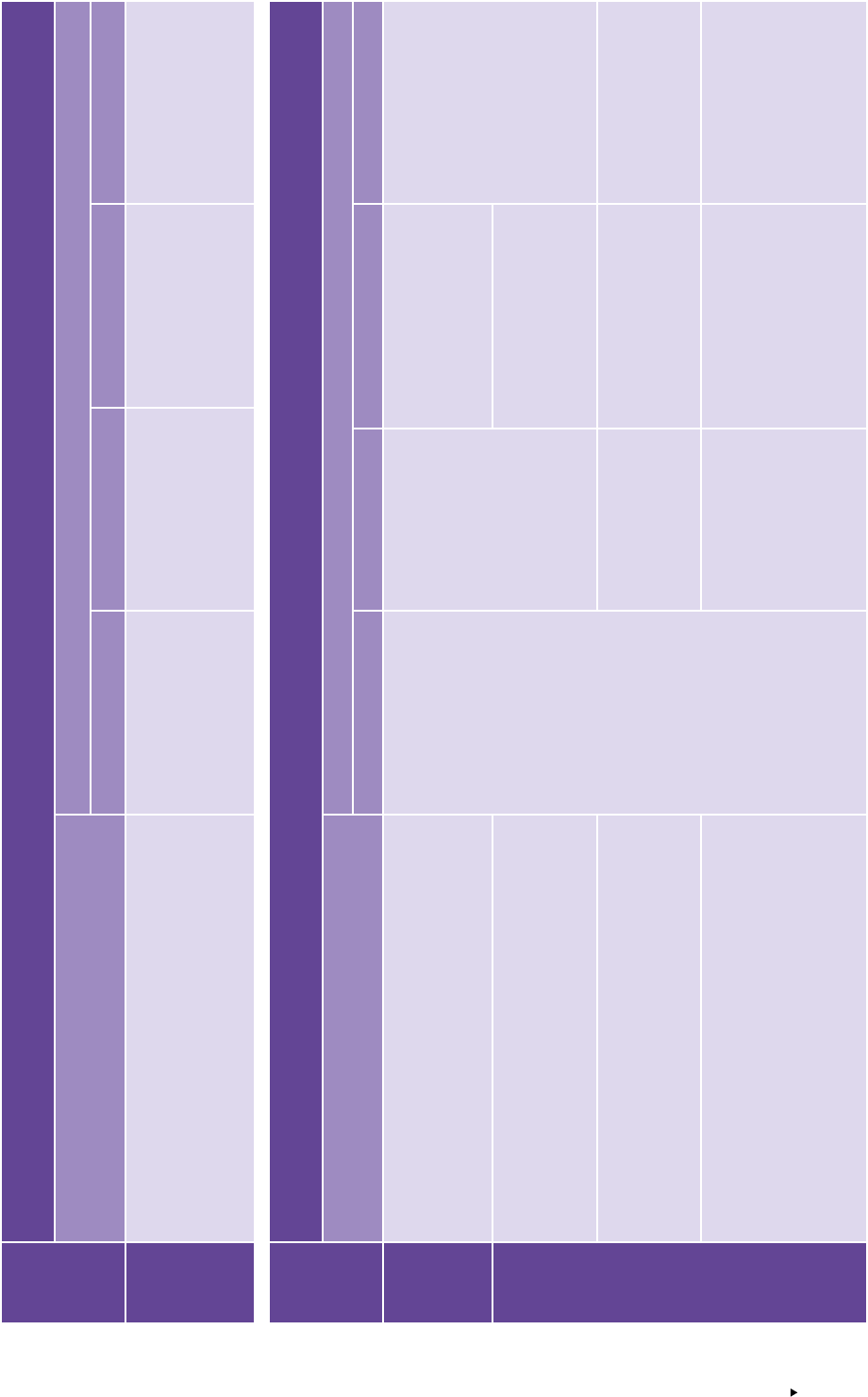

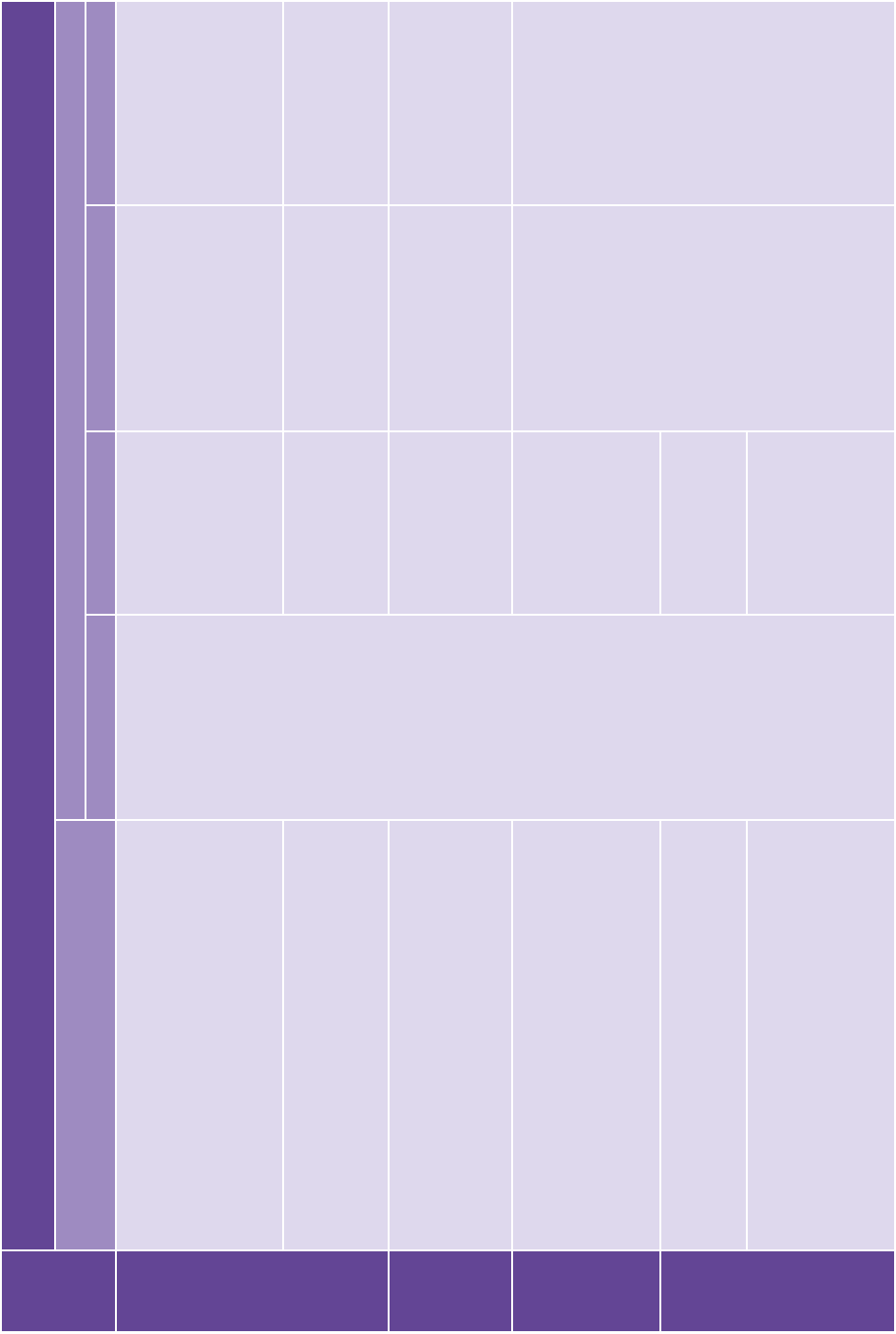

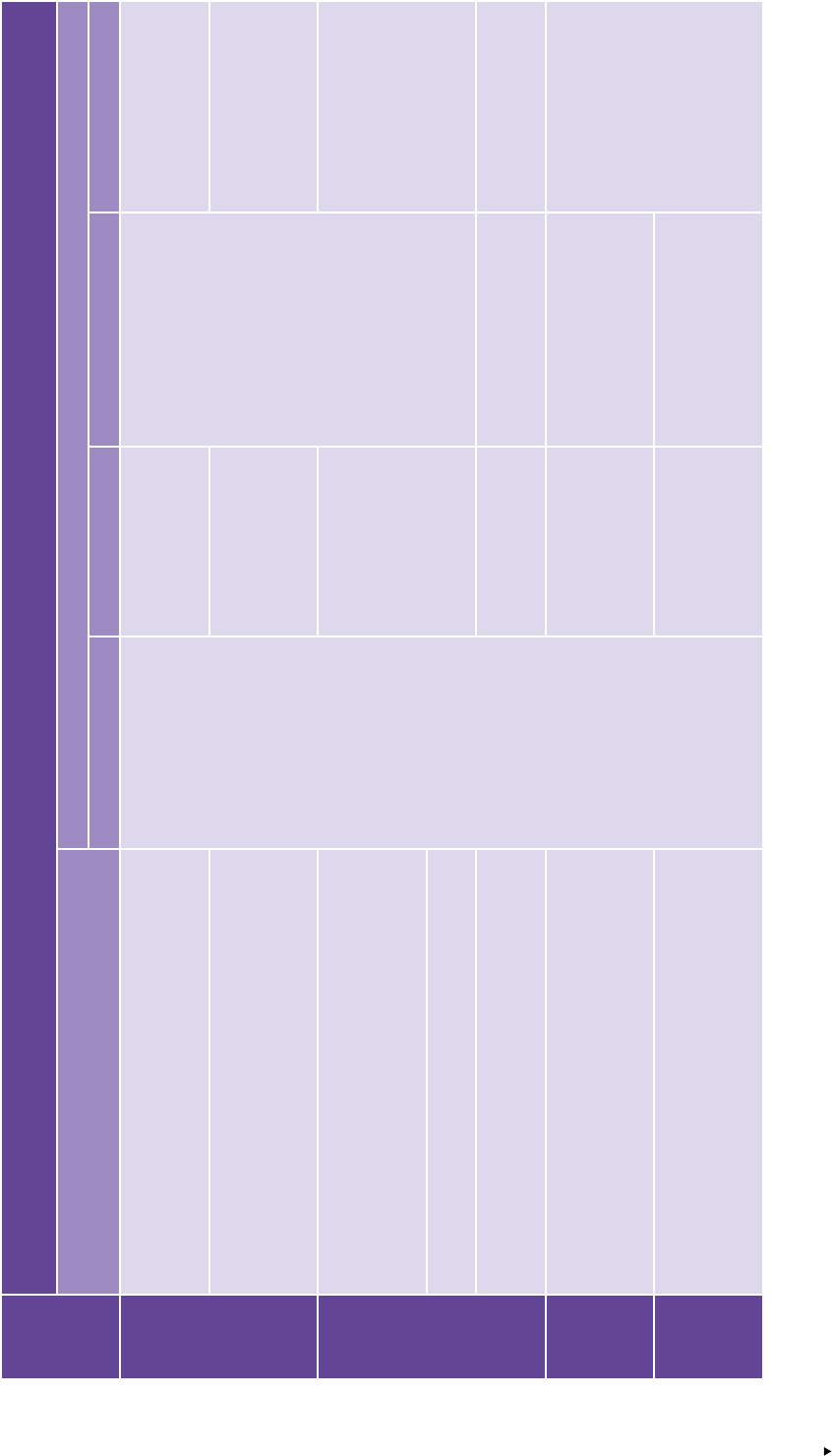

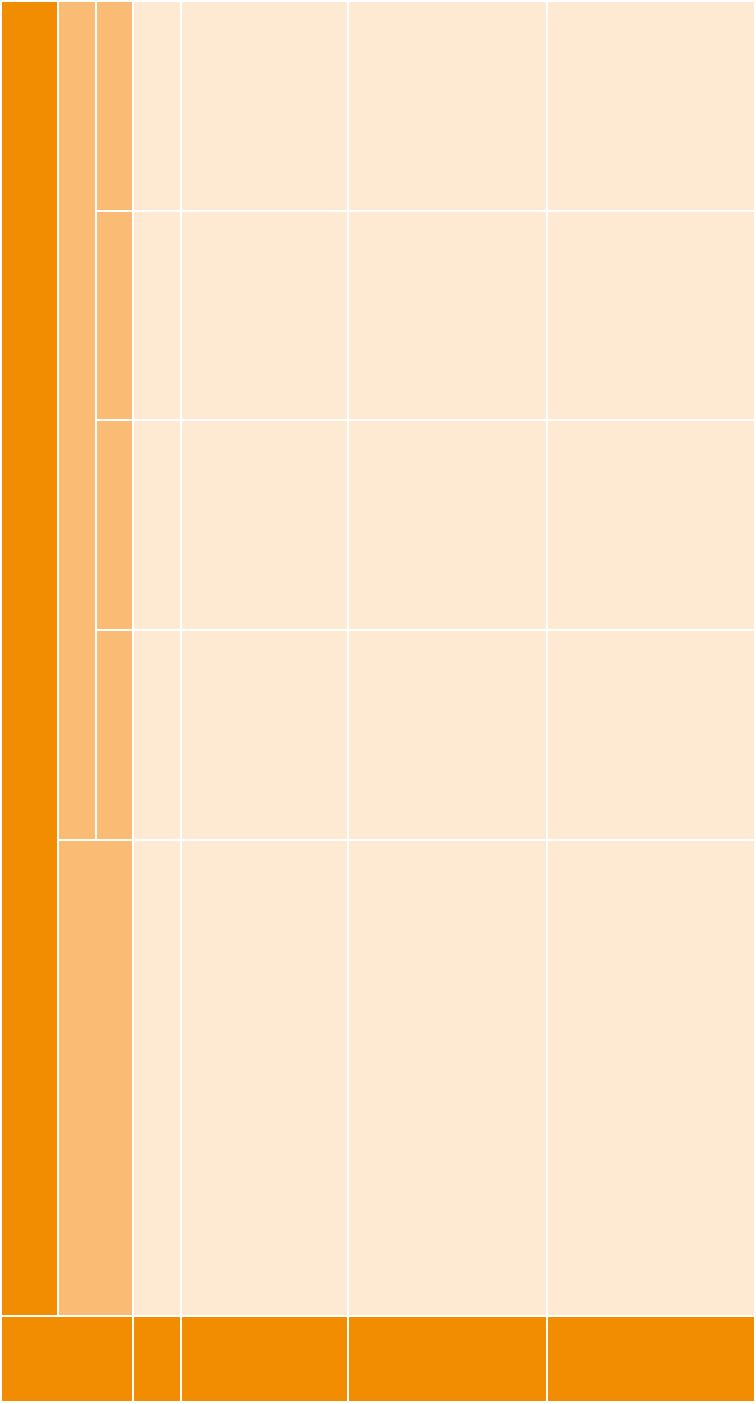

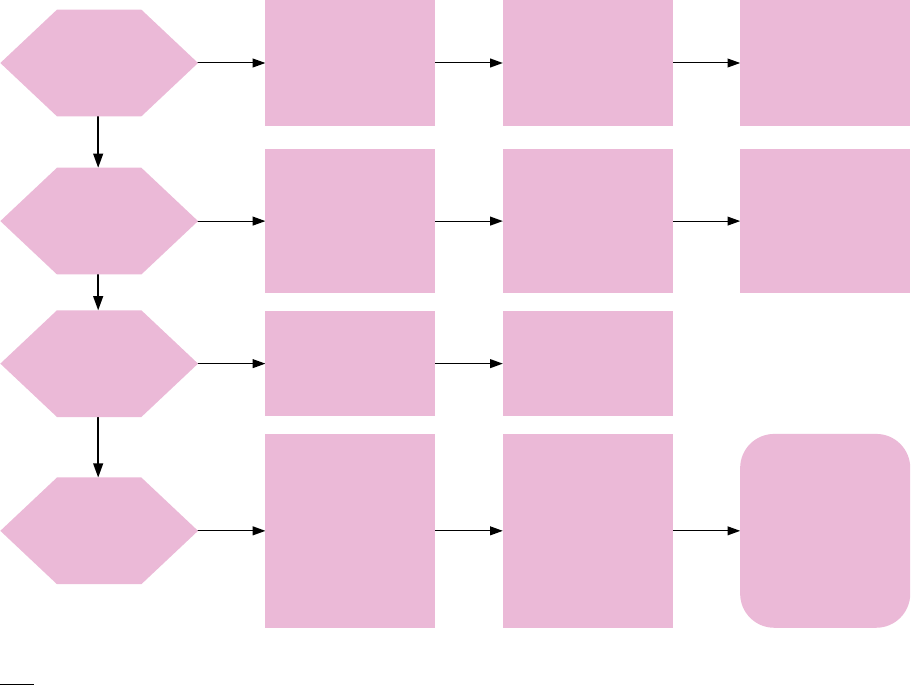

FIGURE 1 THE STRUCTURE OF THE CEFR DESCRIPTIVE SCHEME 32

FIGURE 2 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN RECEPTION, PRODUCTION, INTERACTION AND MEDIATION 34

FIGURE 3 CEFR COMMON REFERENCE LEVELS 36

FIGURE 4 A RAINBOW 36

FIGURE 5 THE CONVENTIONAL SIX COLOURS 36

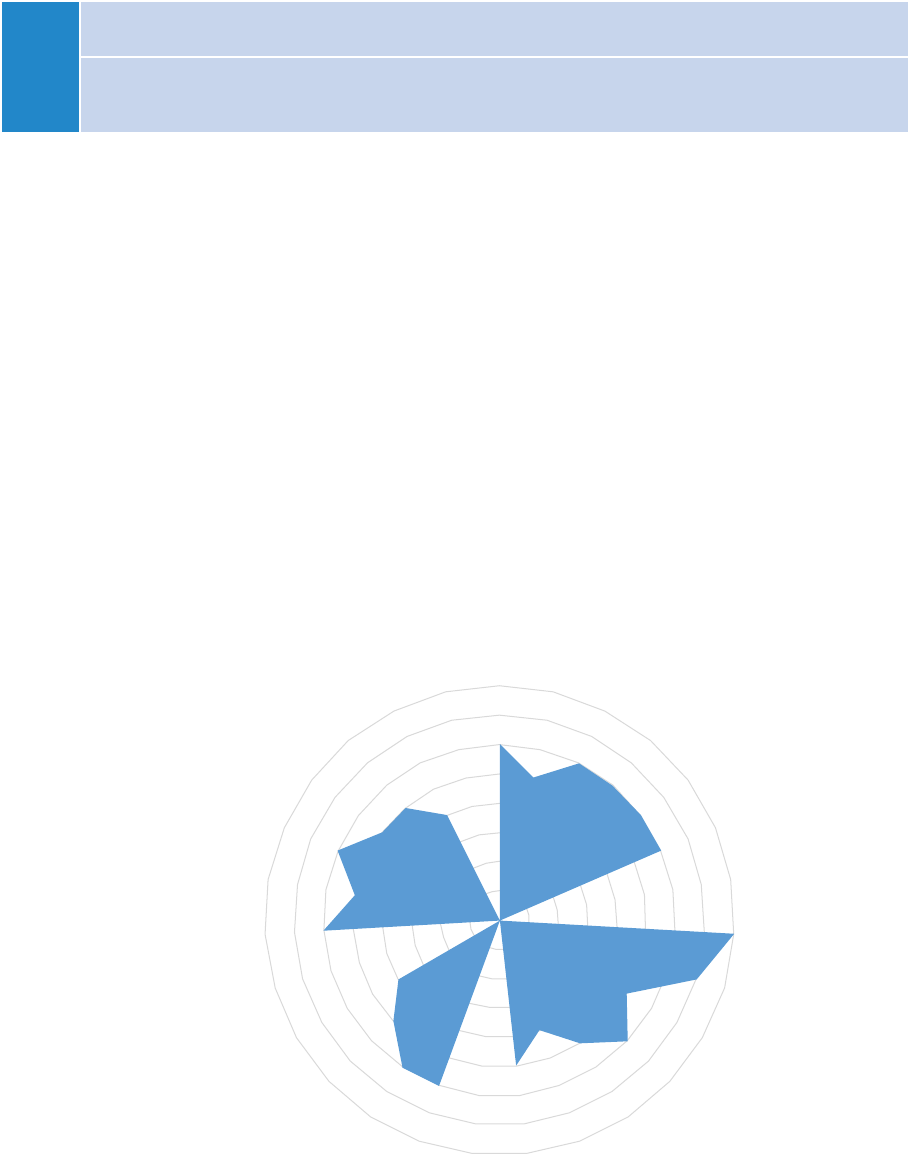

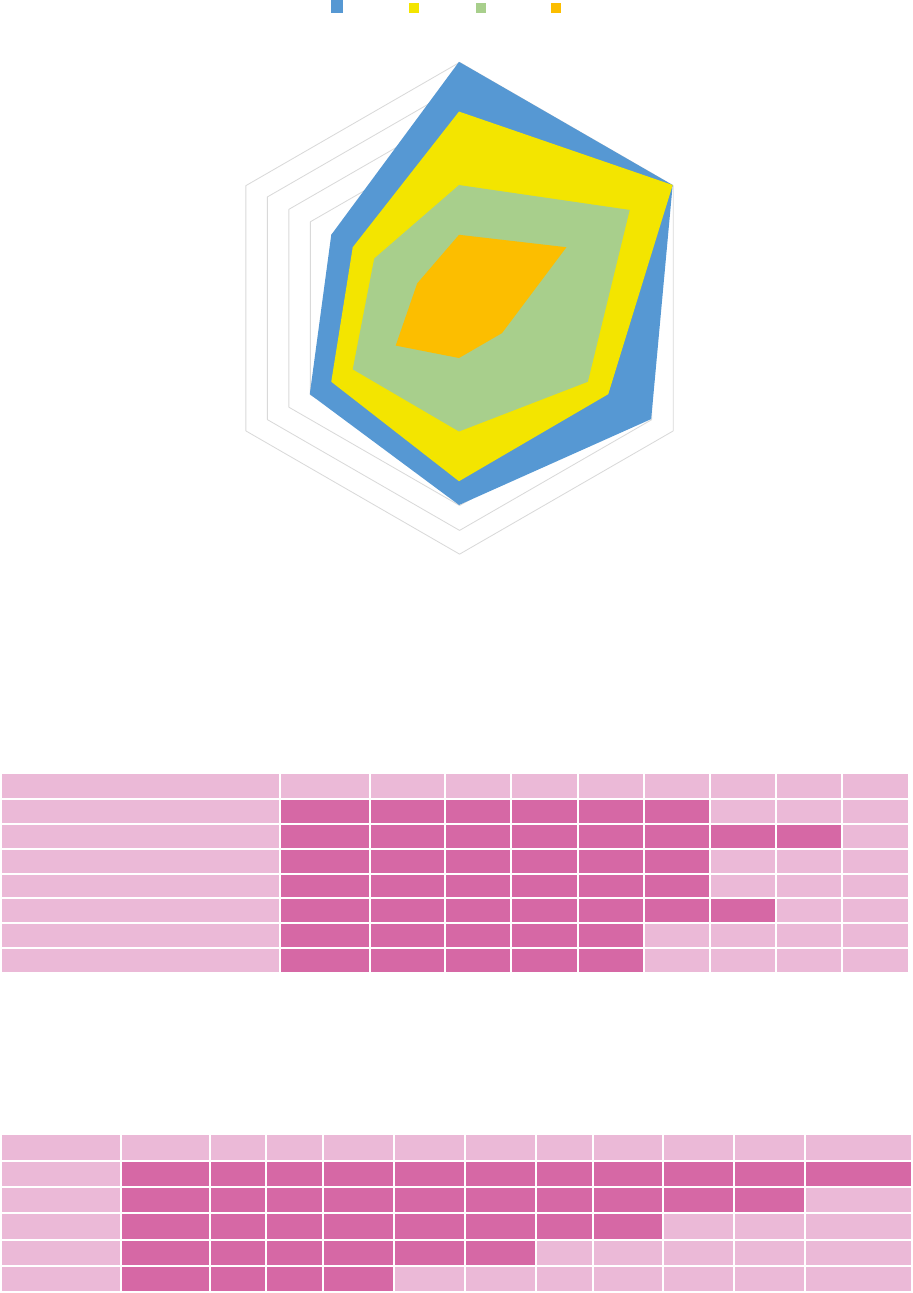

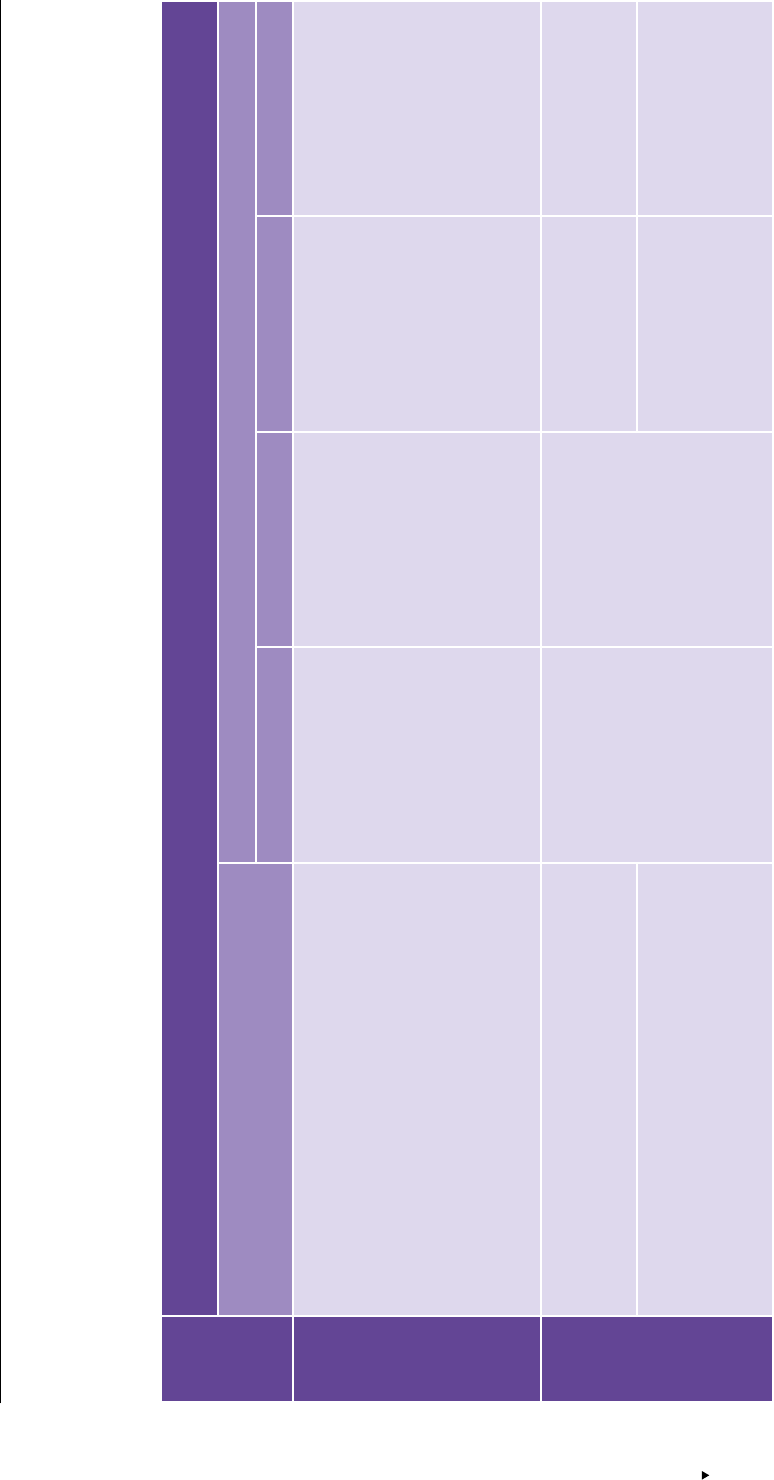

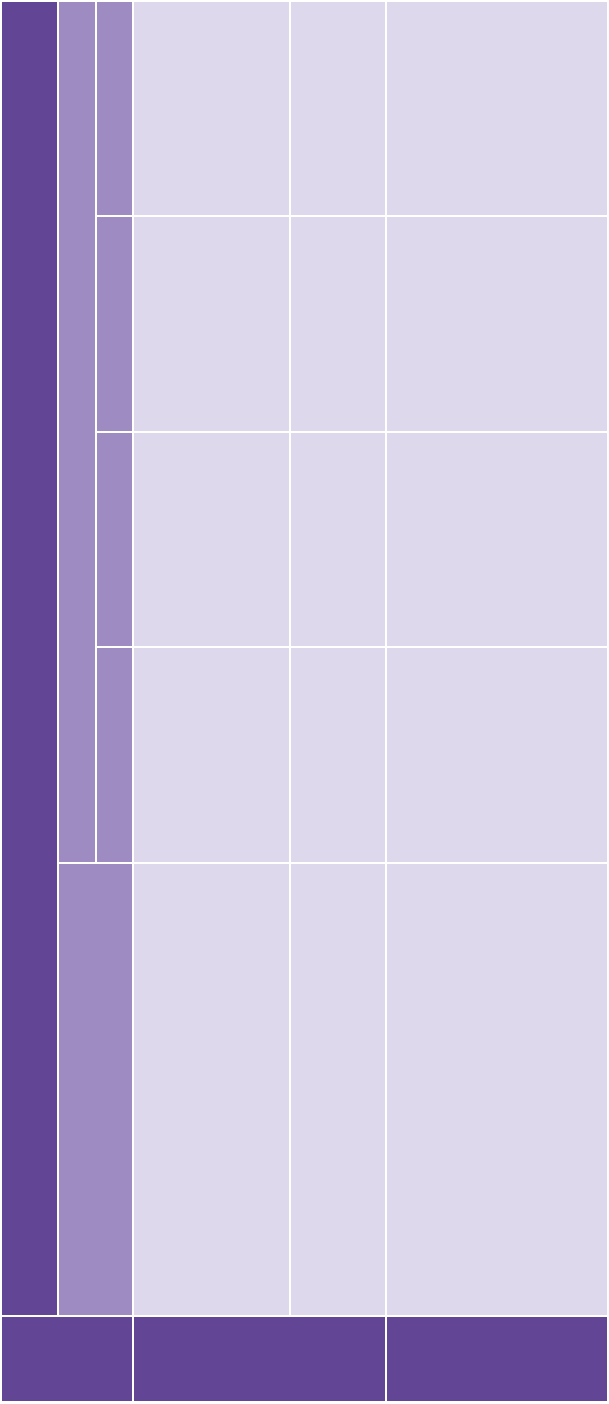

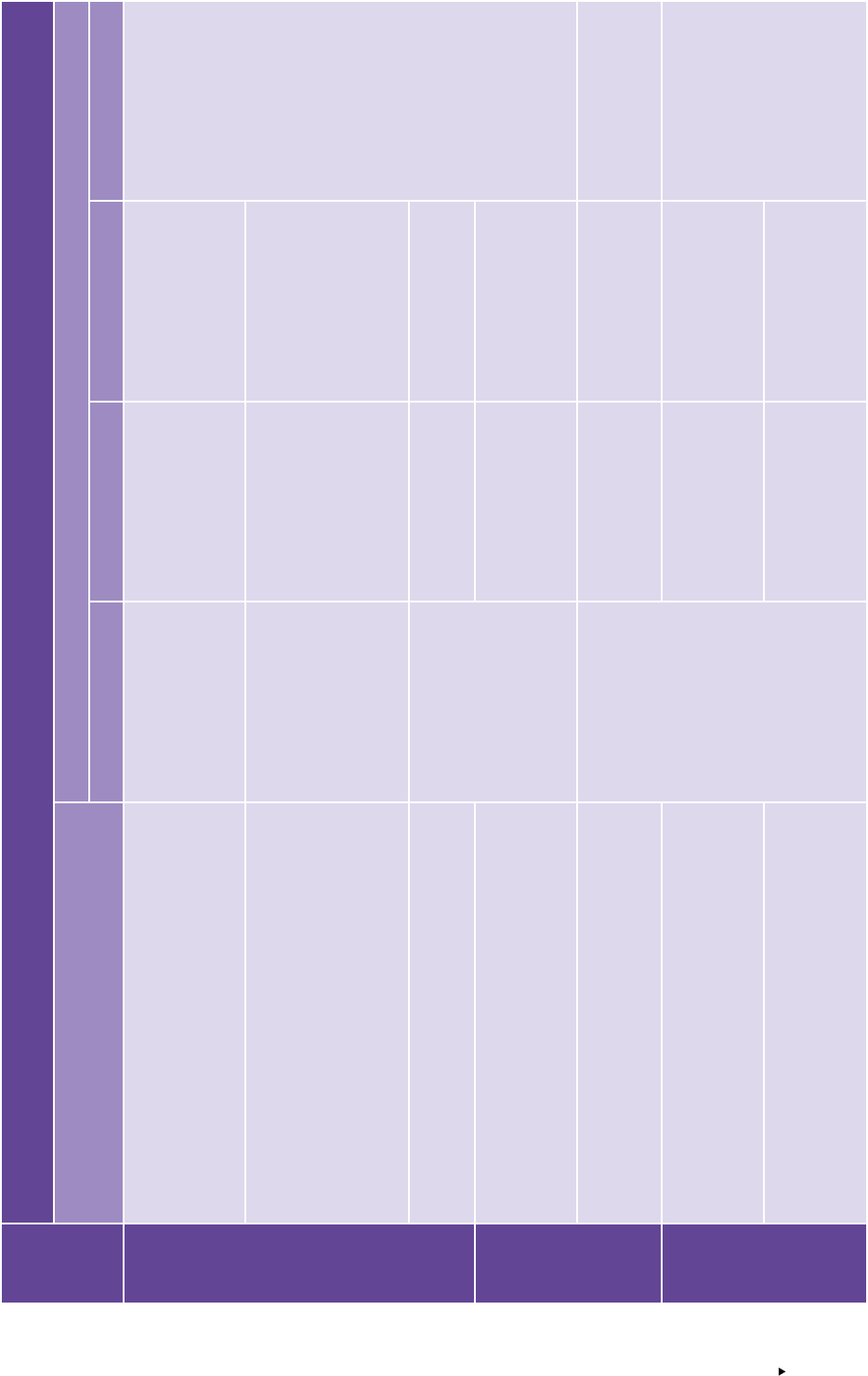

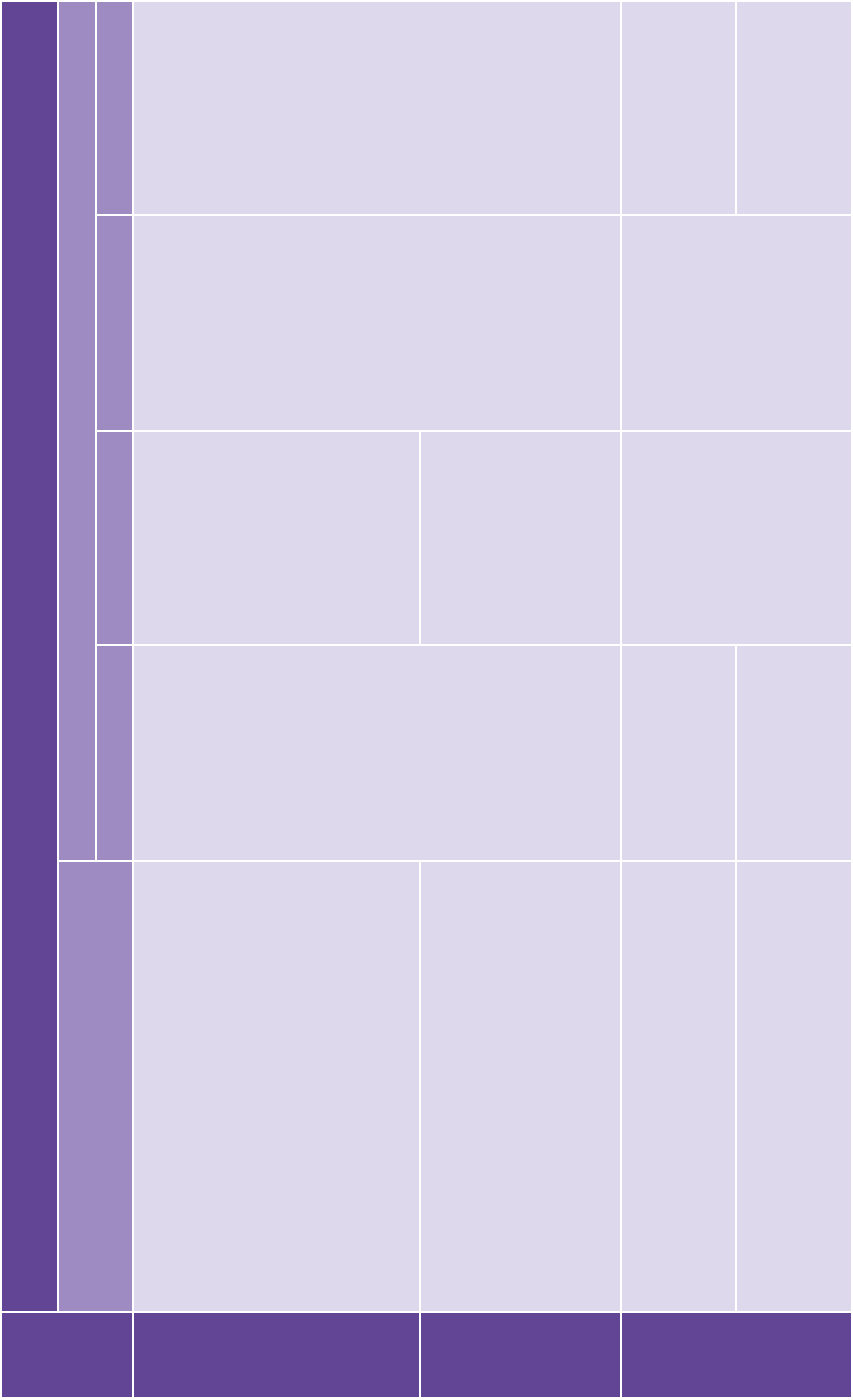

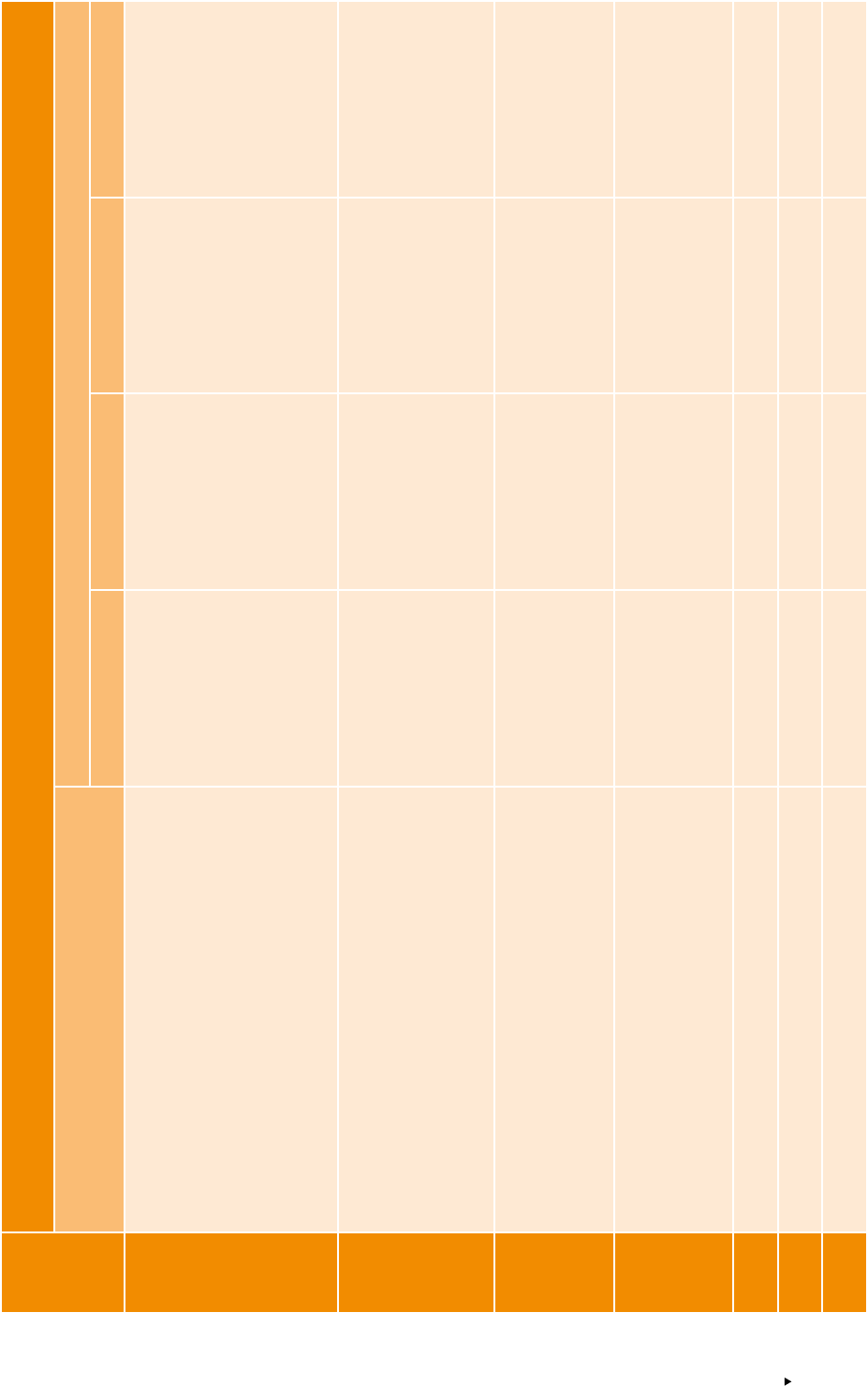

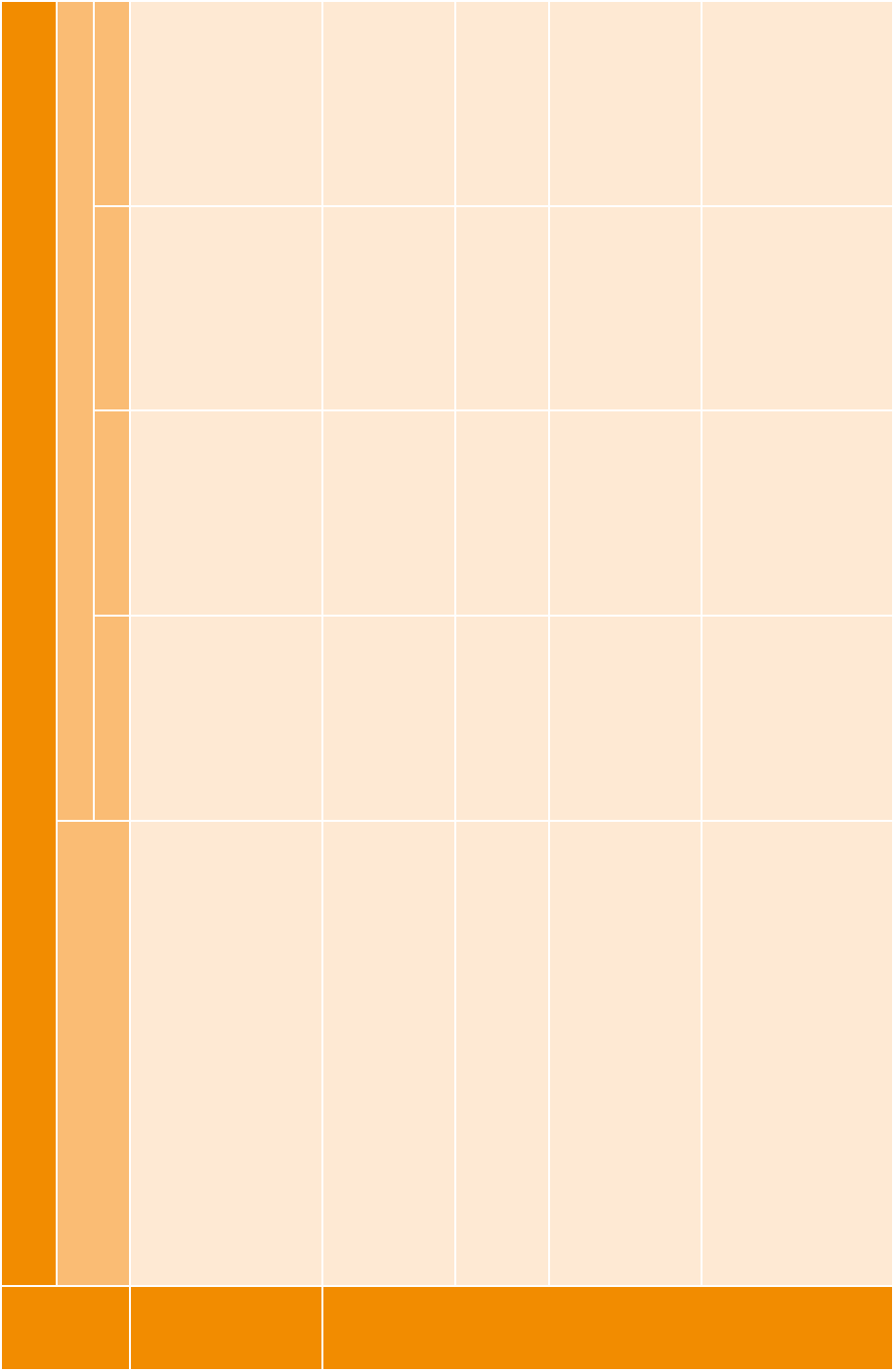

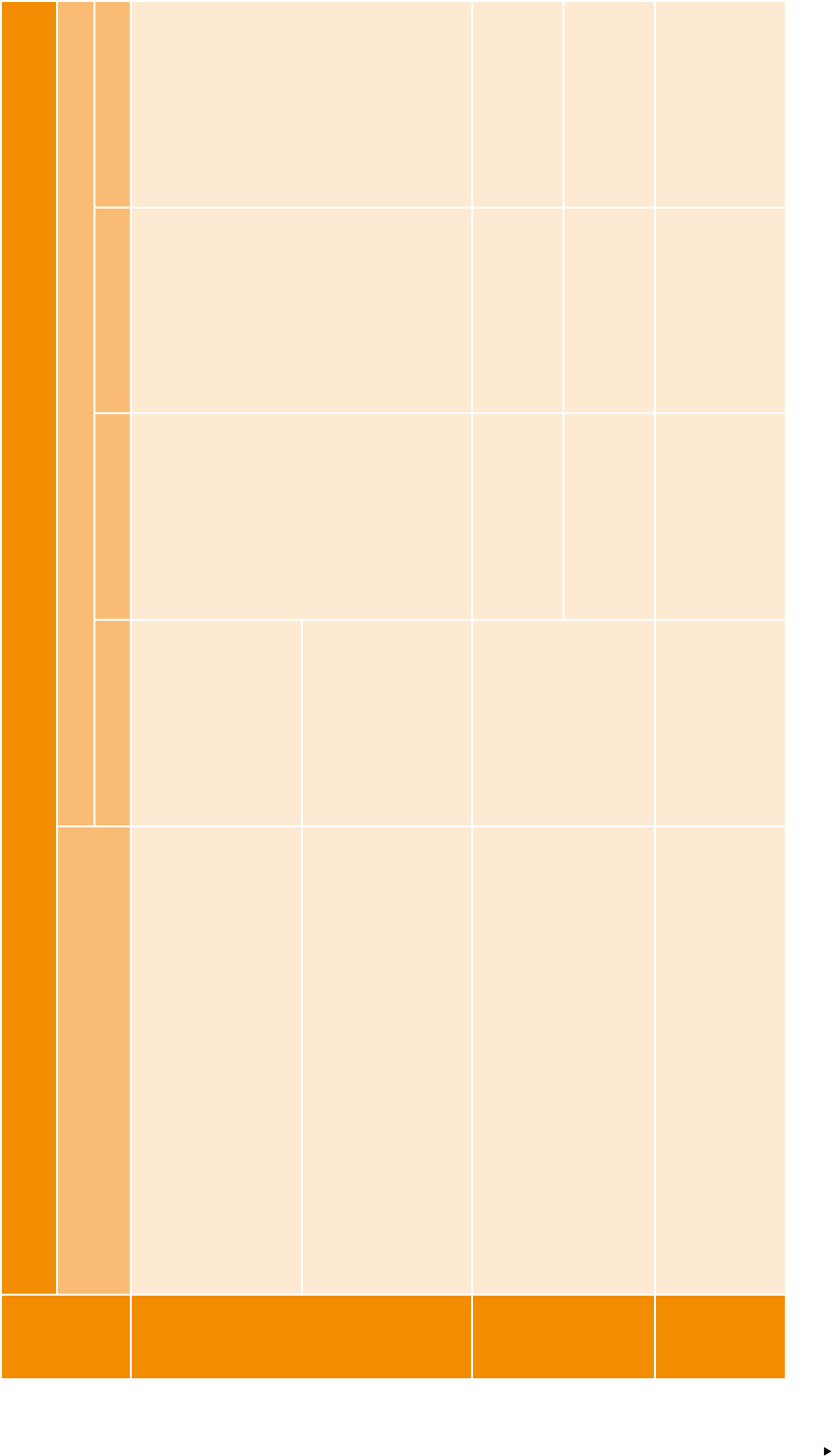

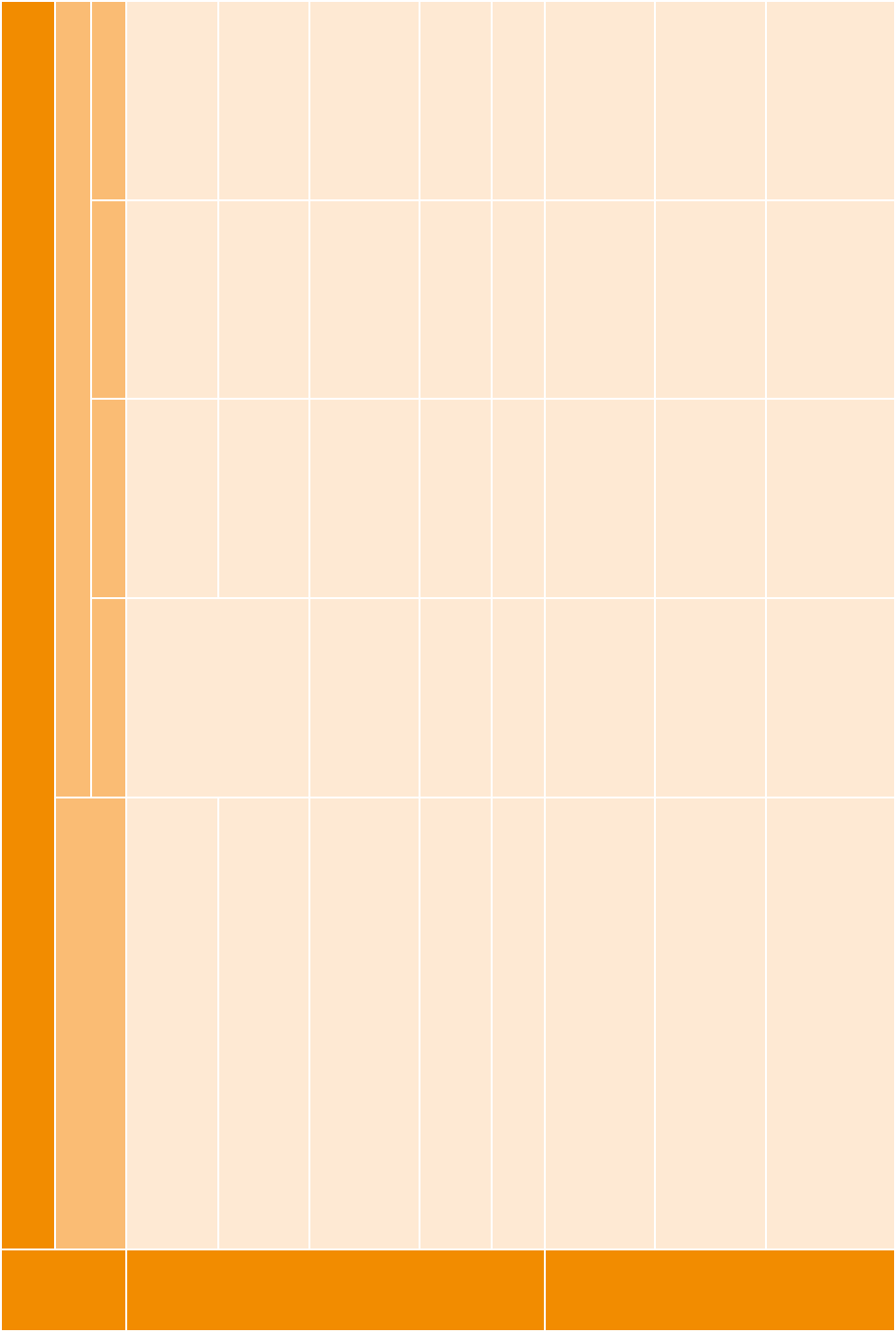

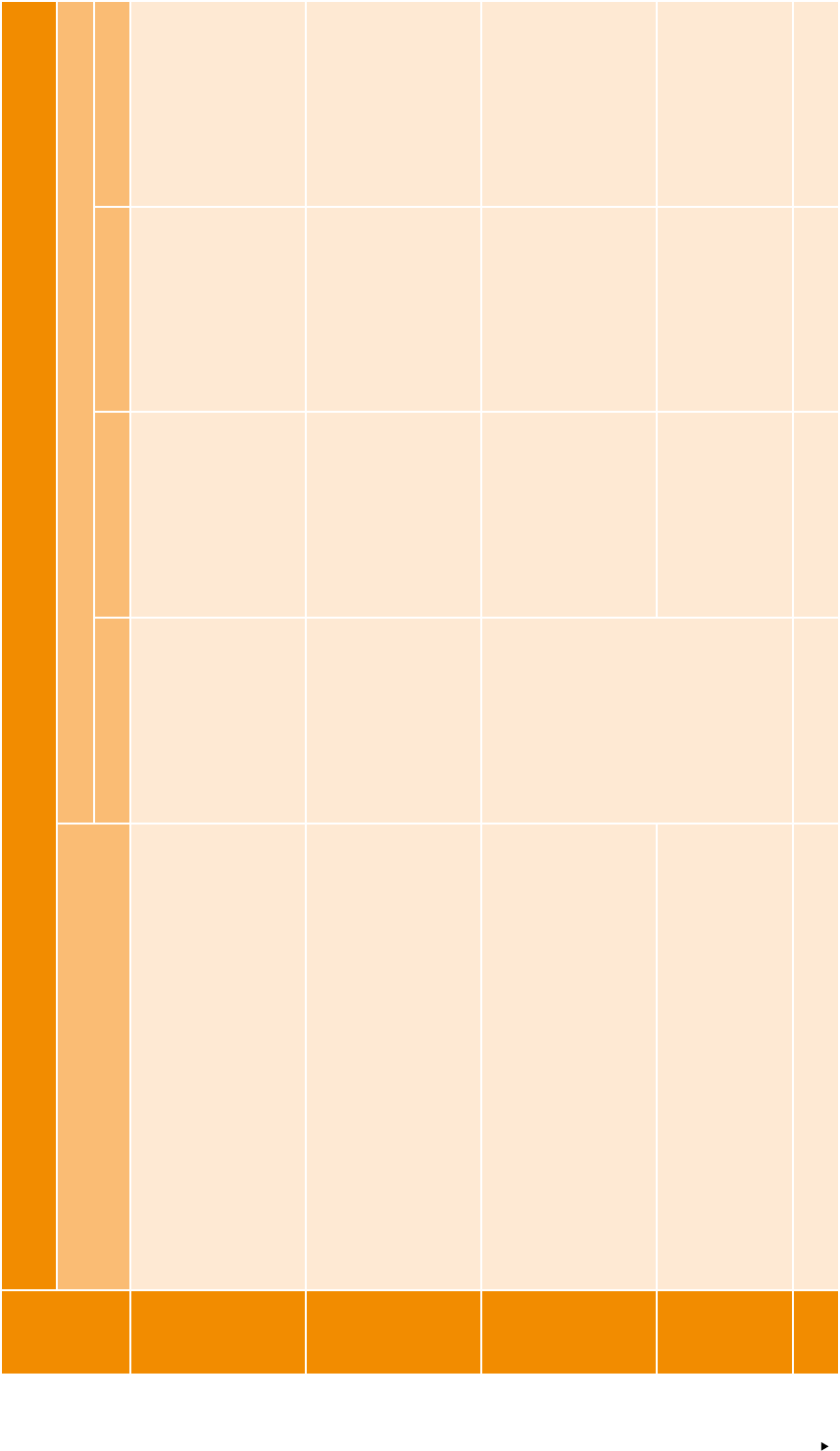

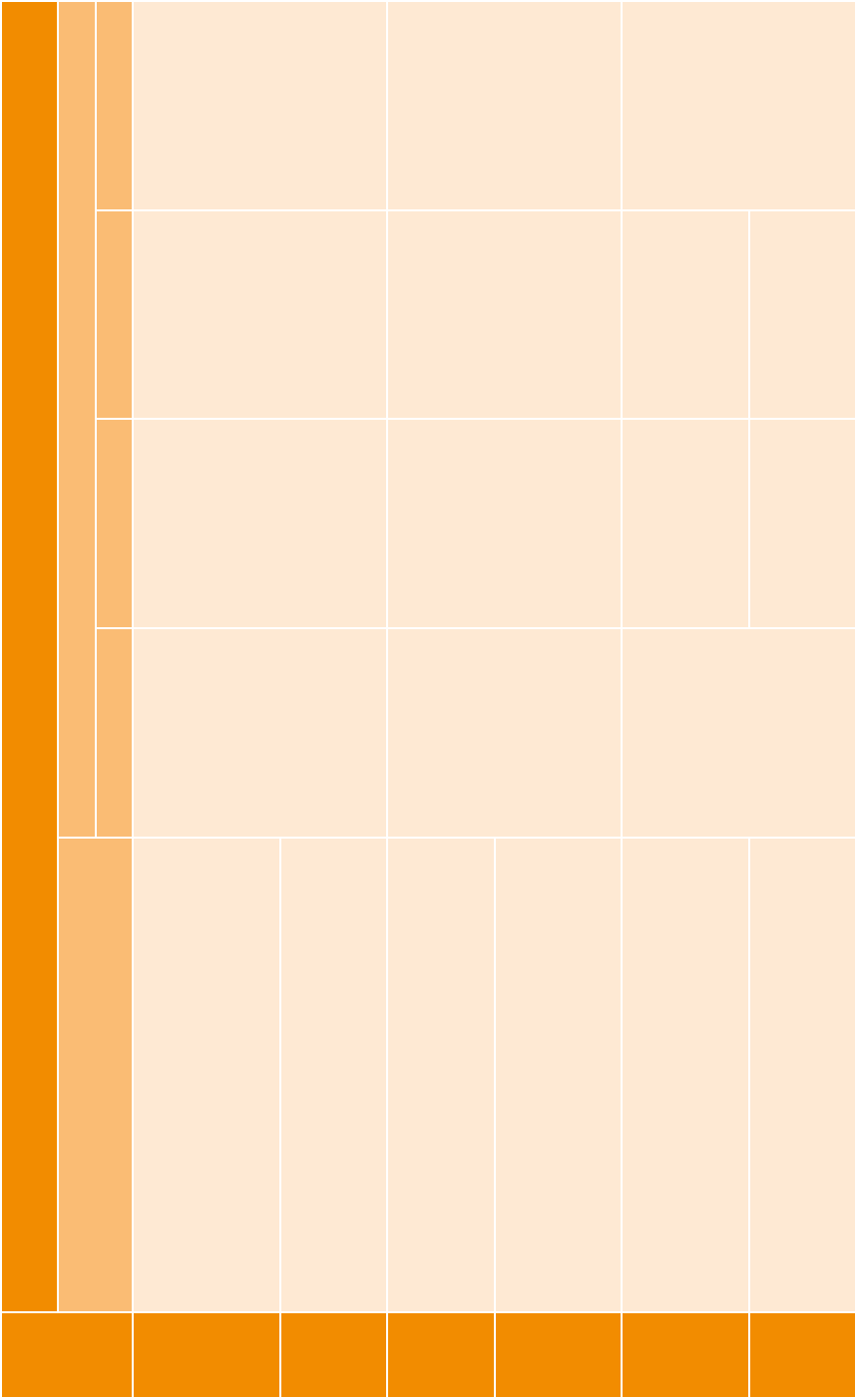

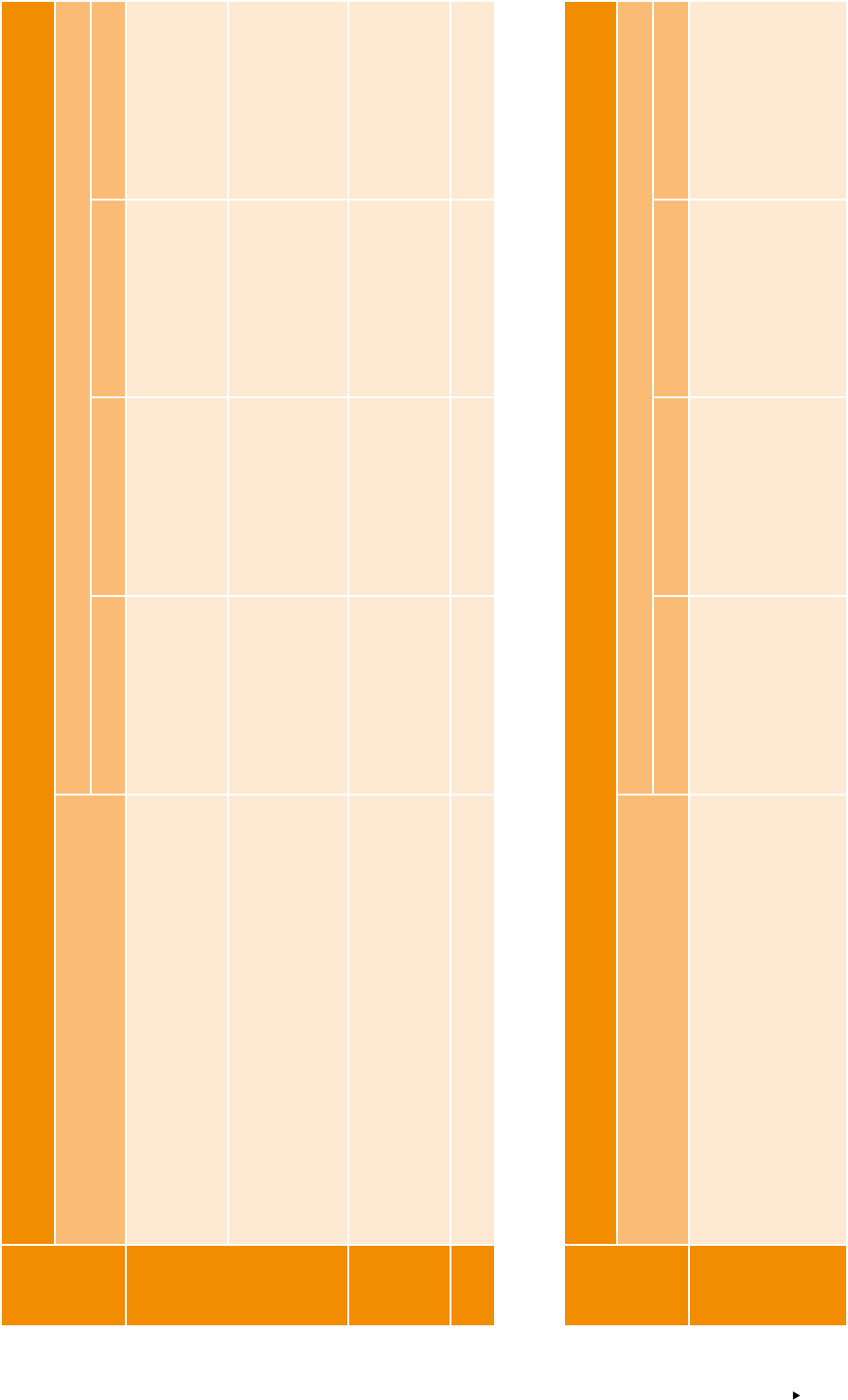

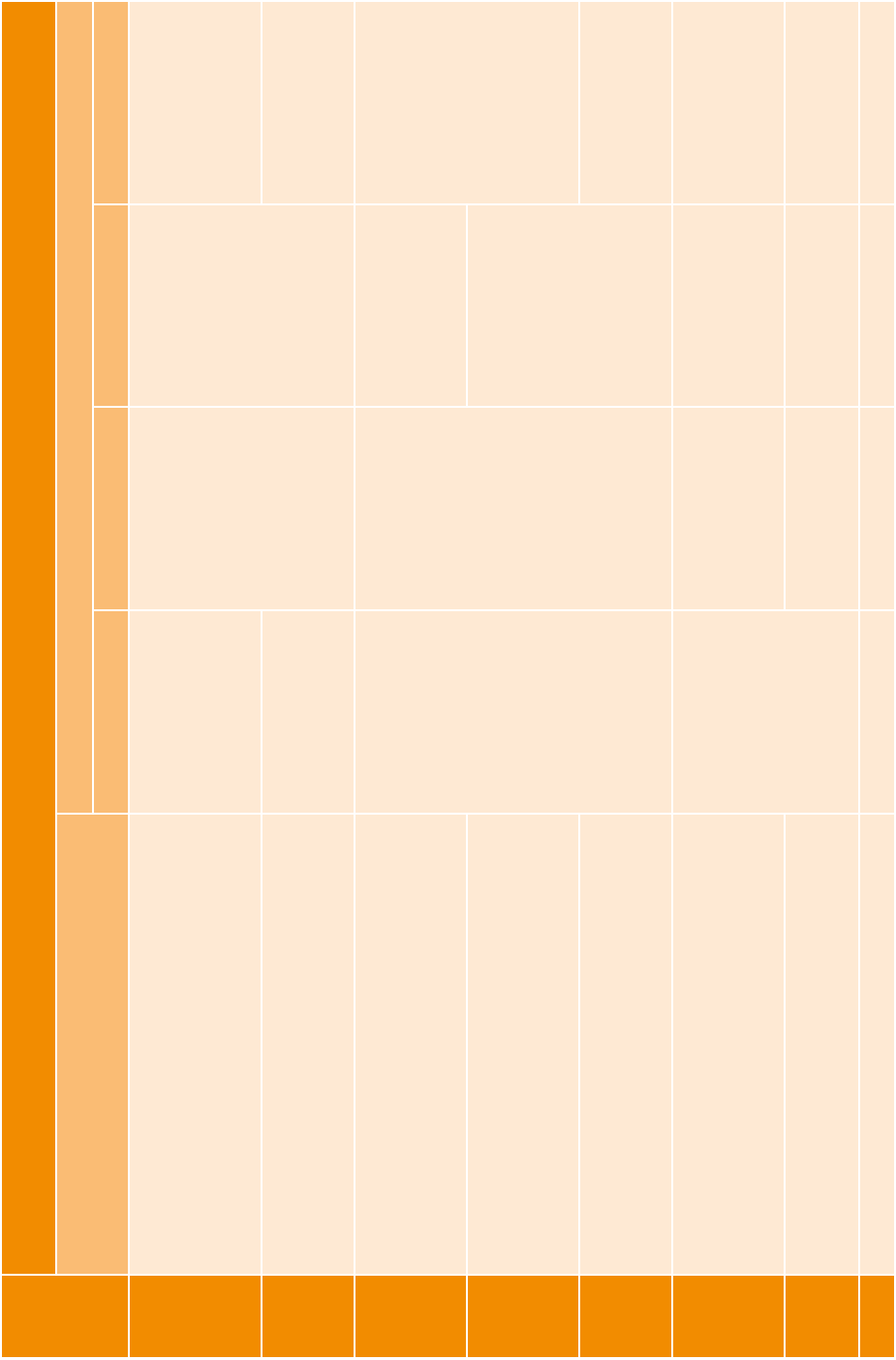

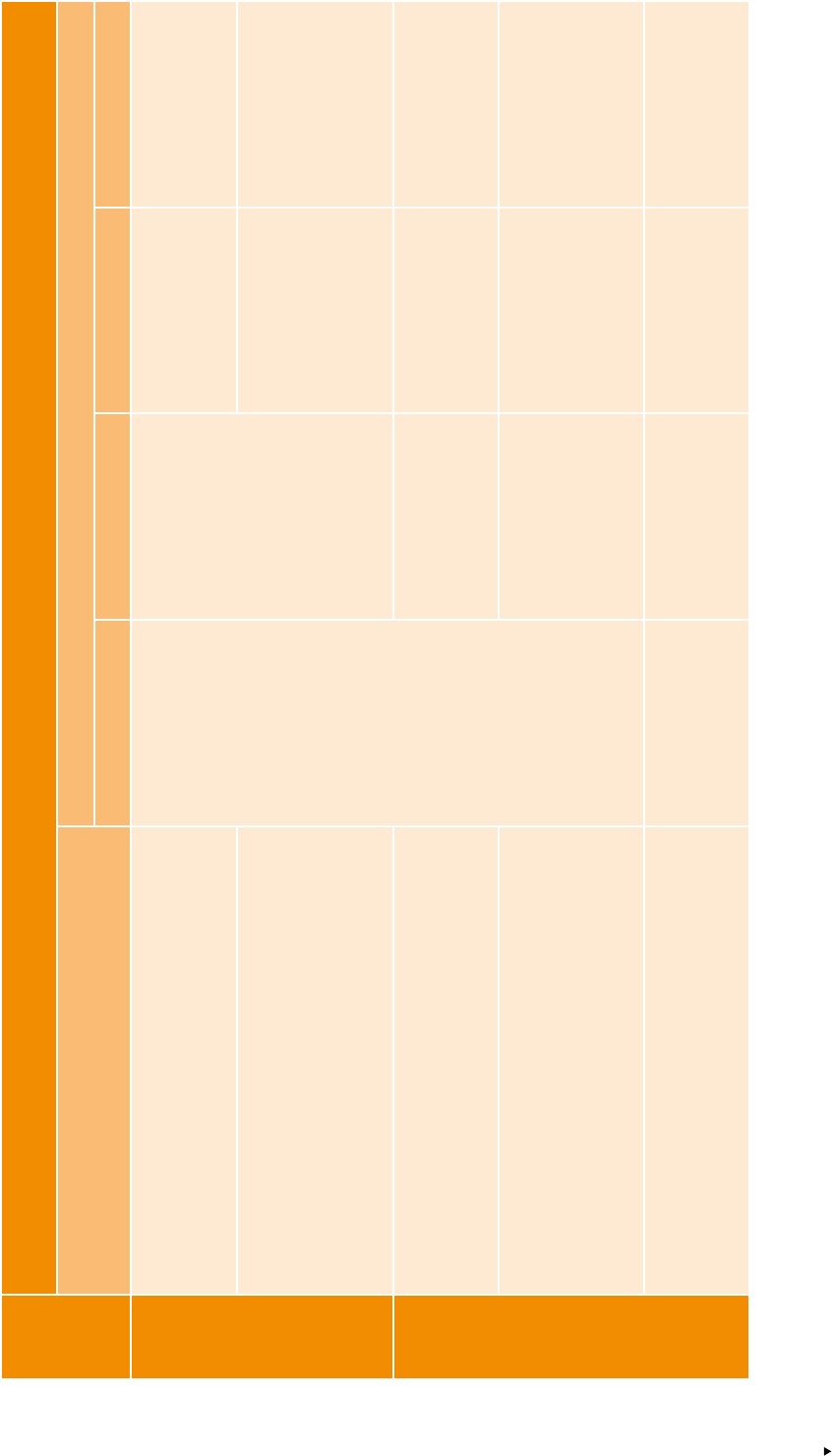

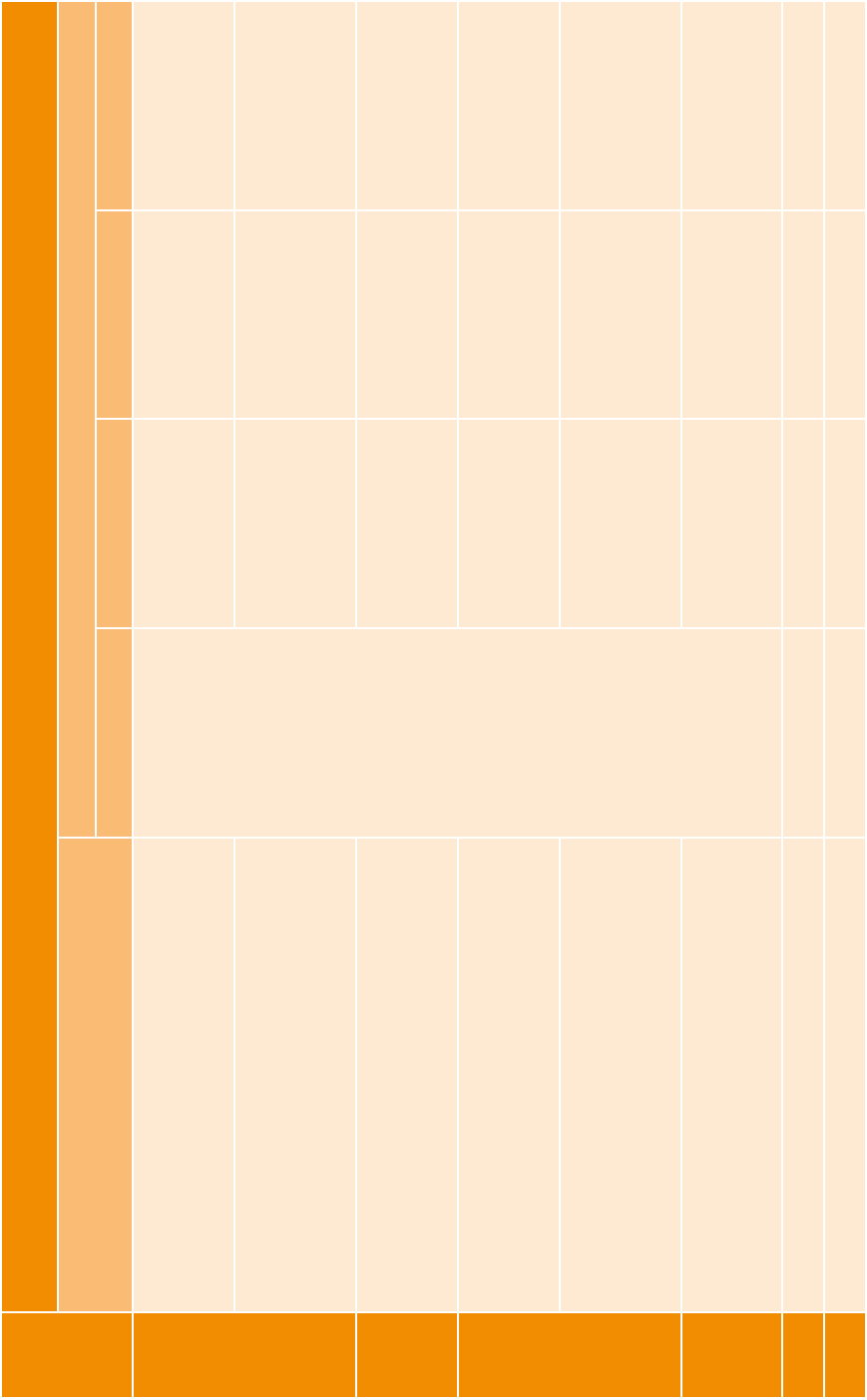

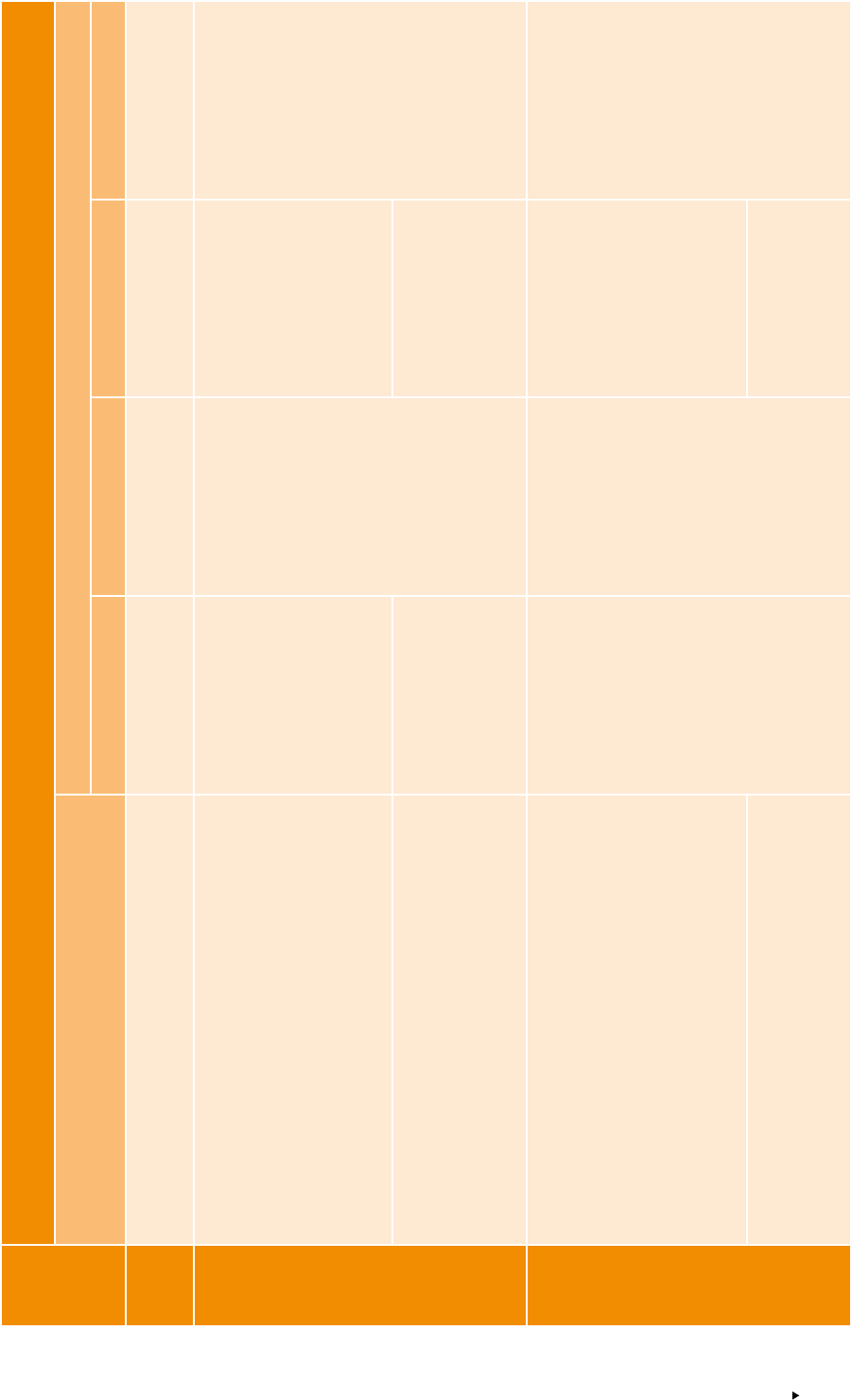

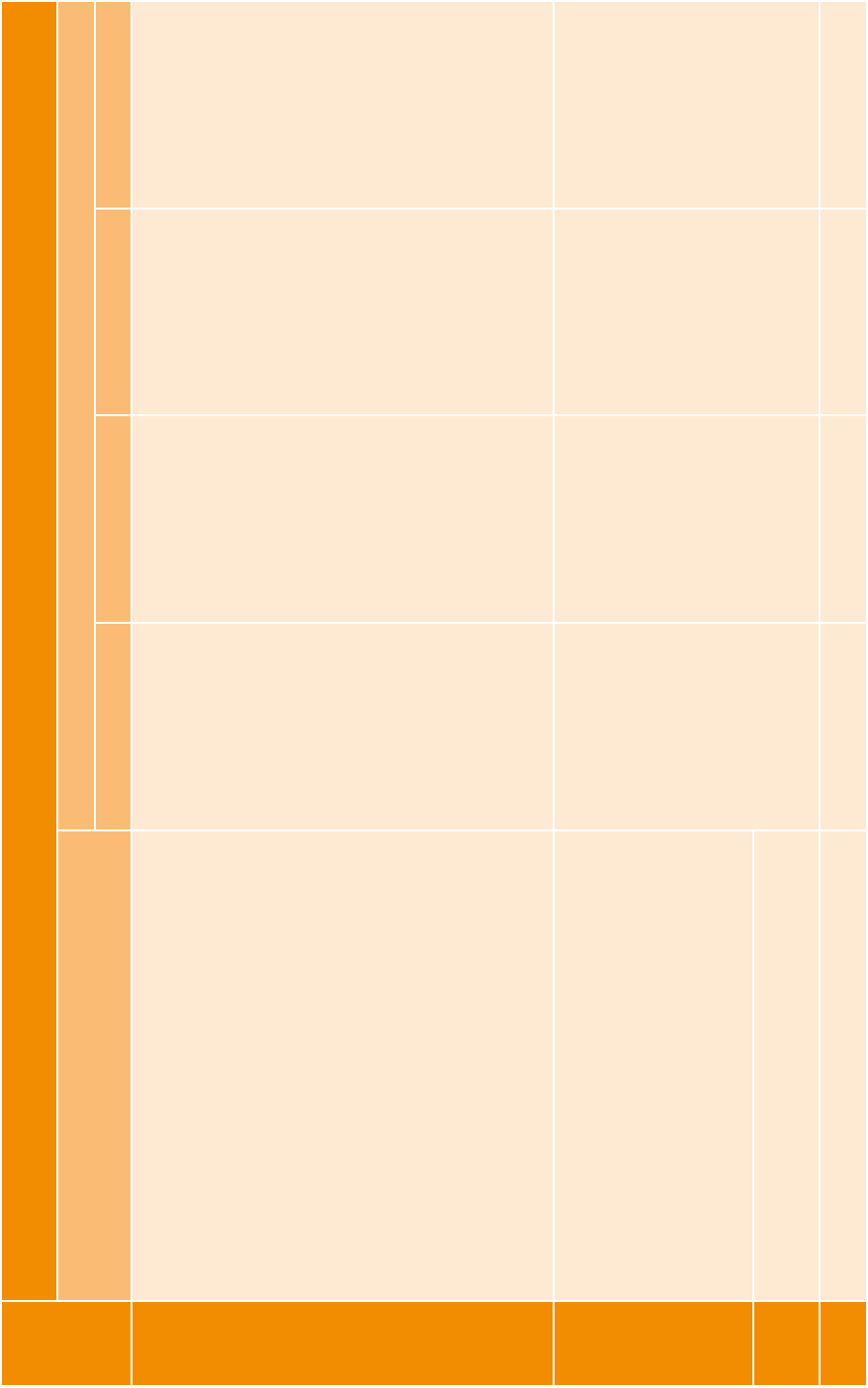

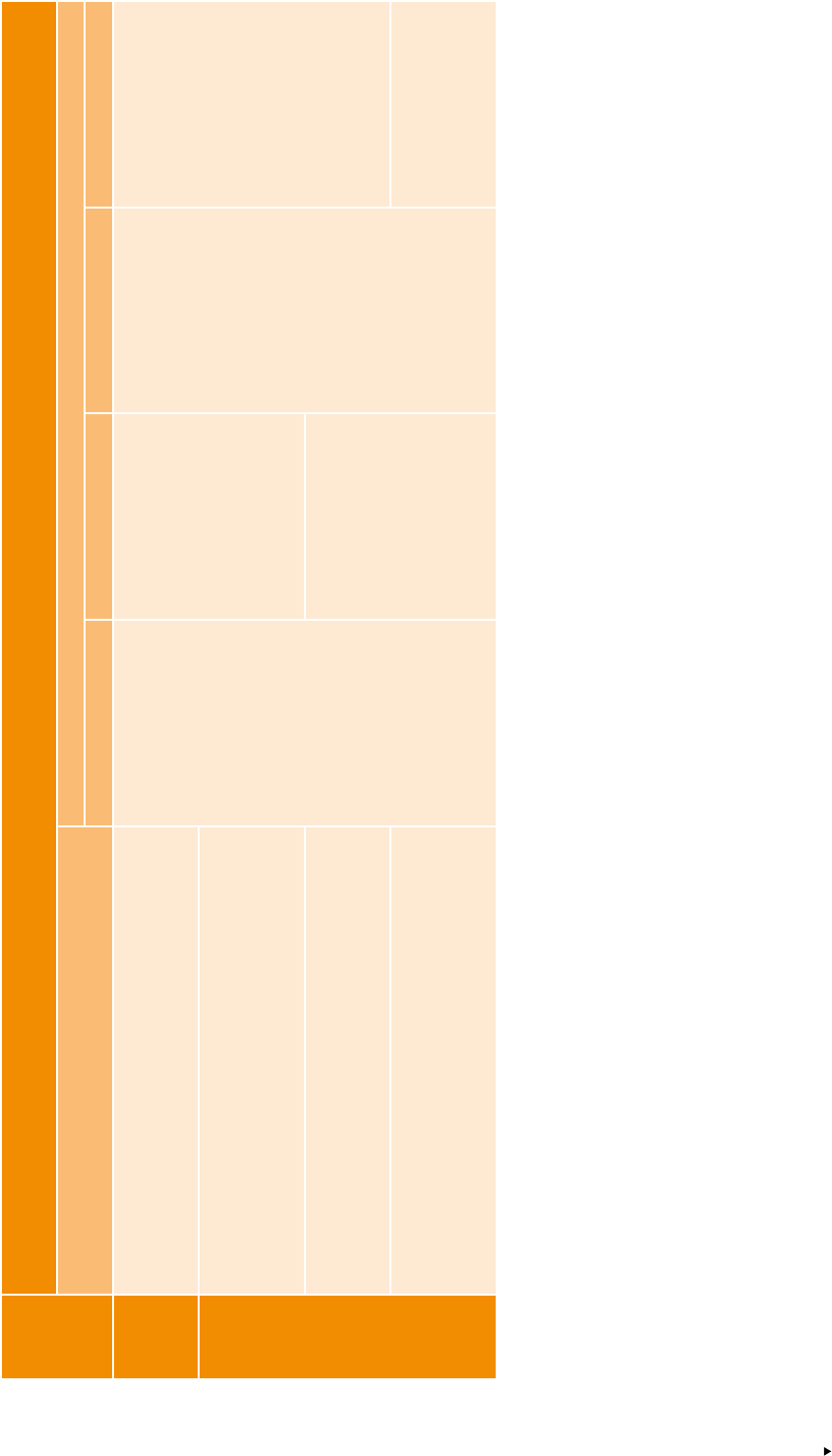

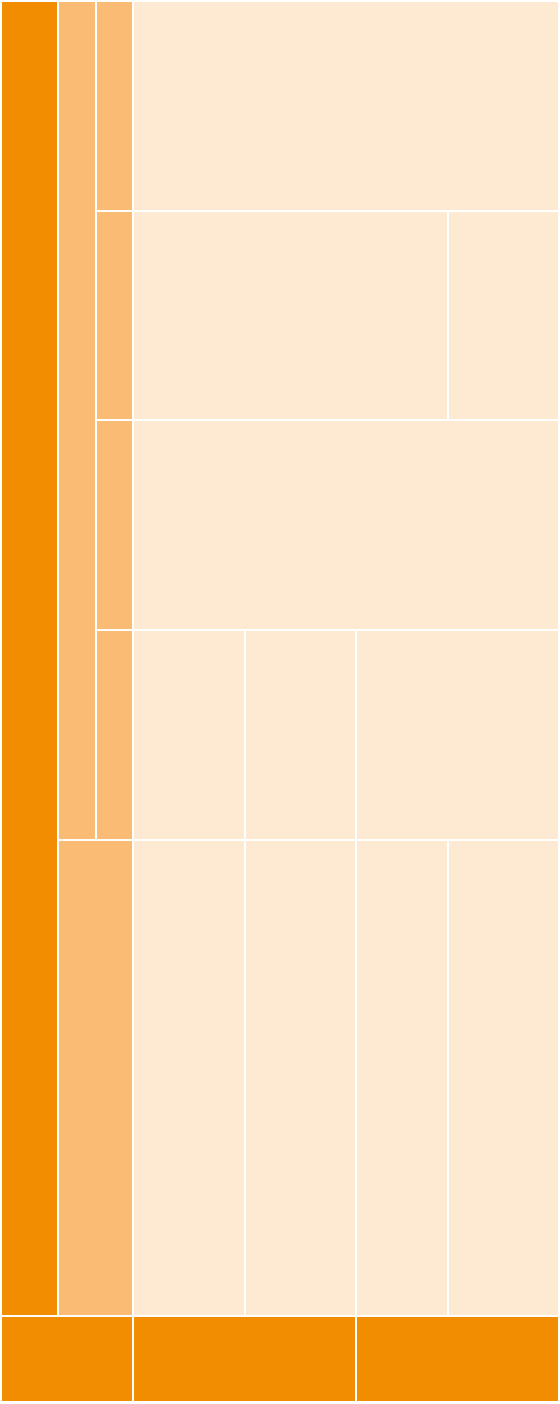

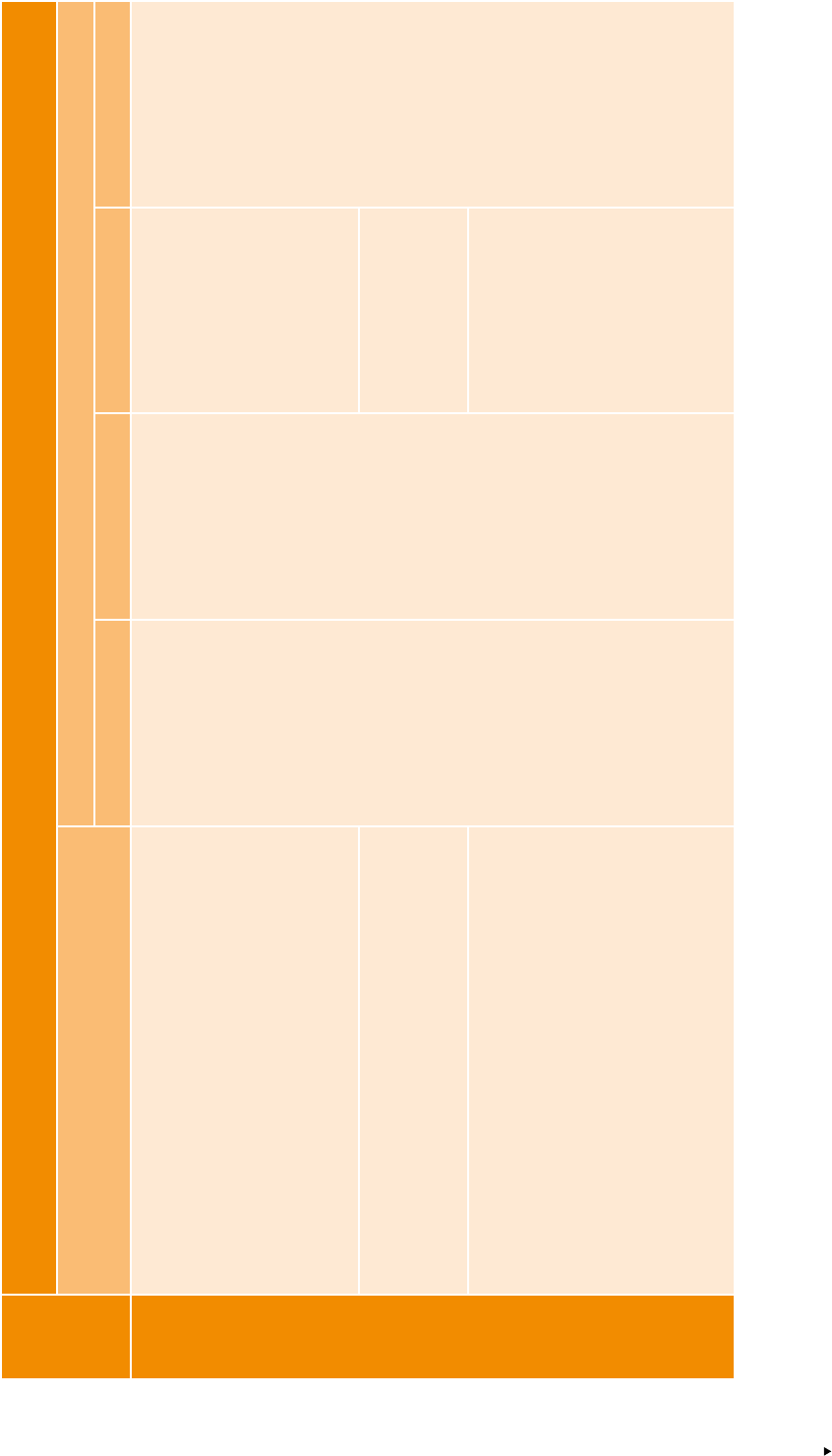

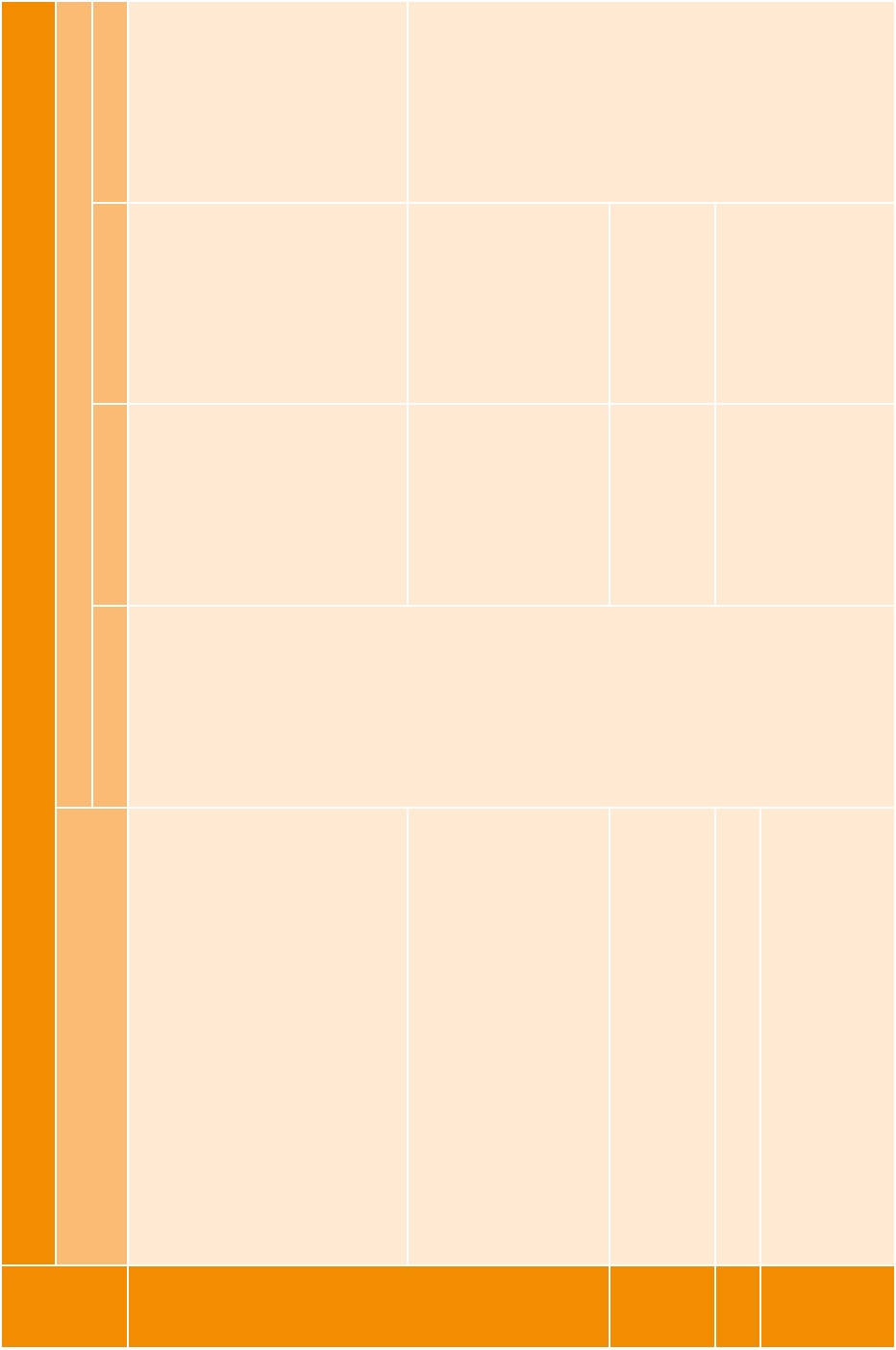

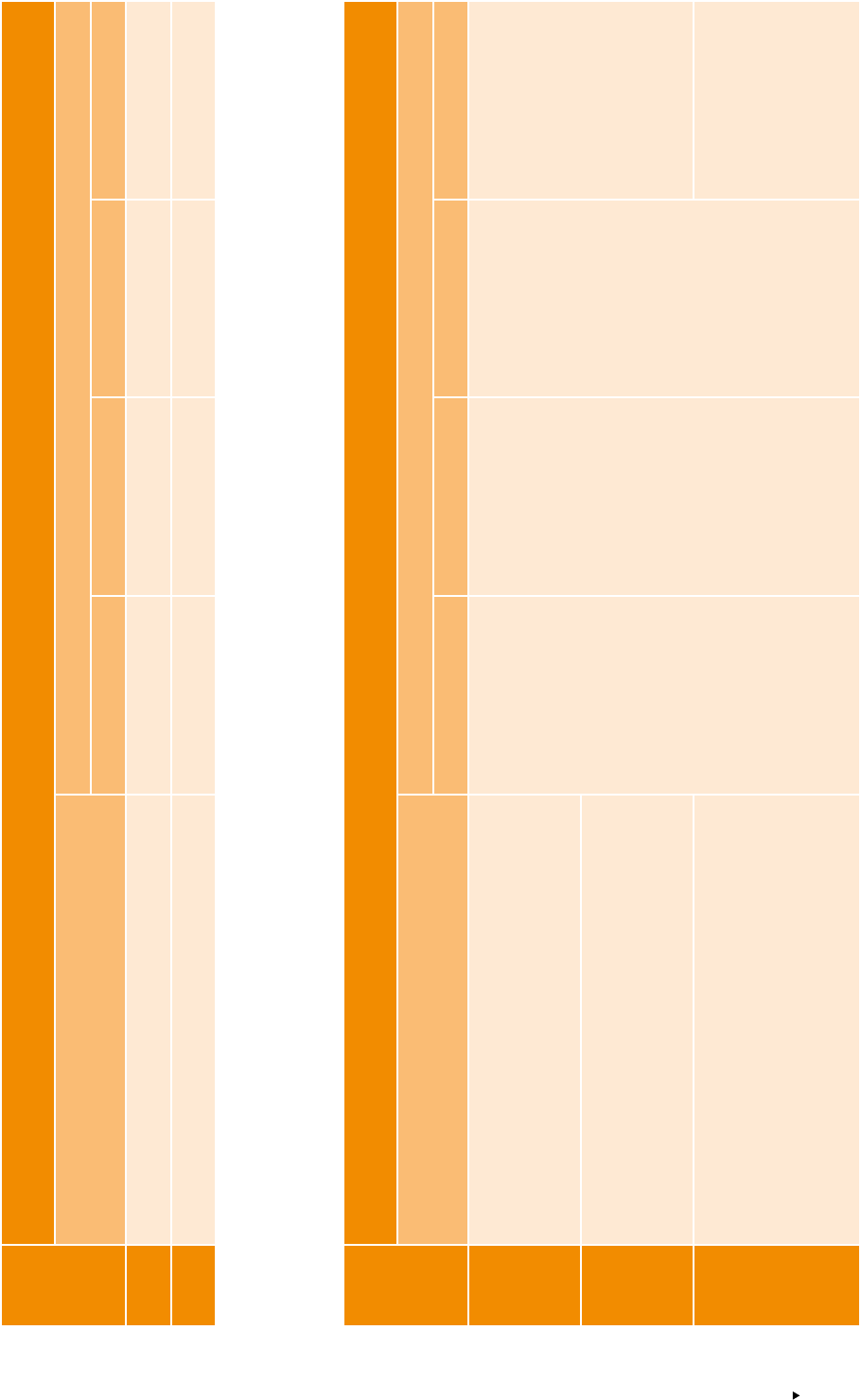

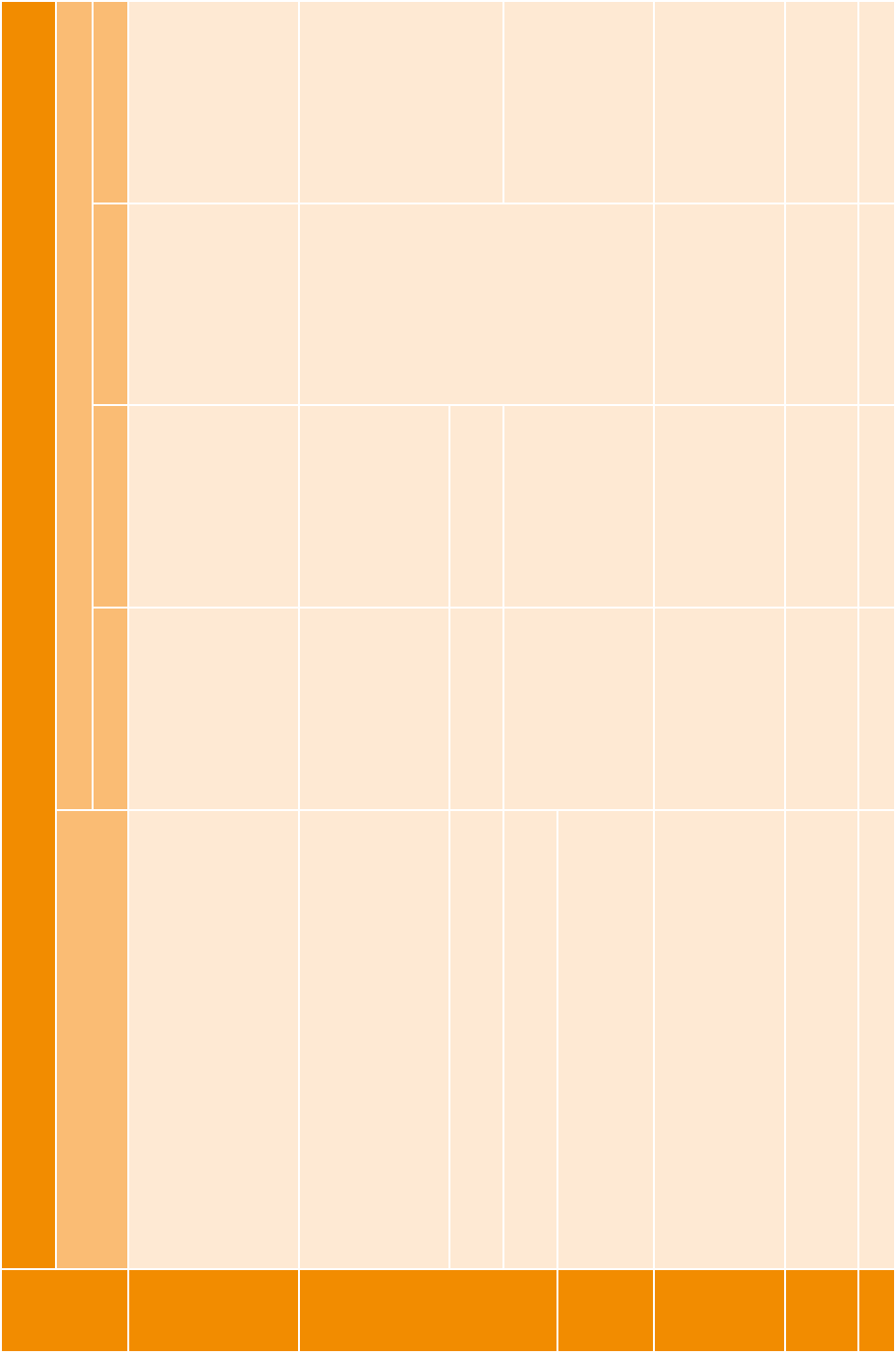

FIGURE 6 A FICTIONAL PROFILE OF NEEDS IN AN ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE LOWER SECONDARY CLIL 38

FIGURE 7 A PROFILE OF NEEDS IN AN ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE

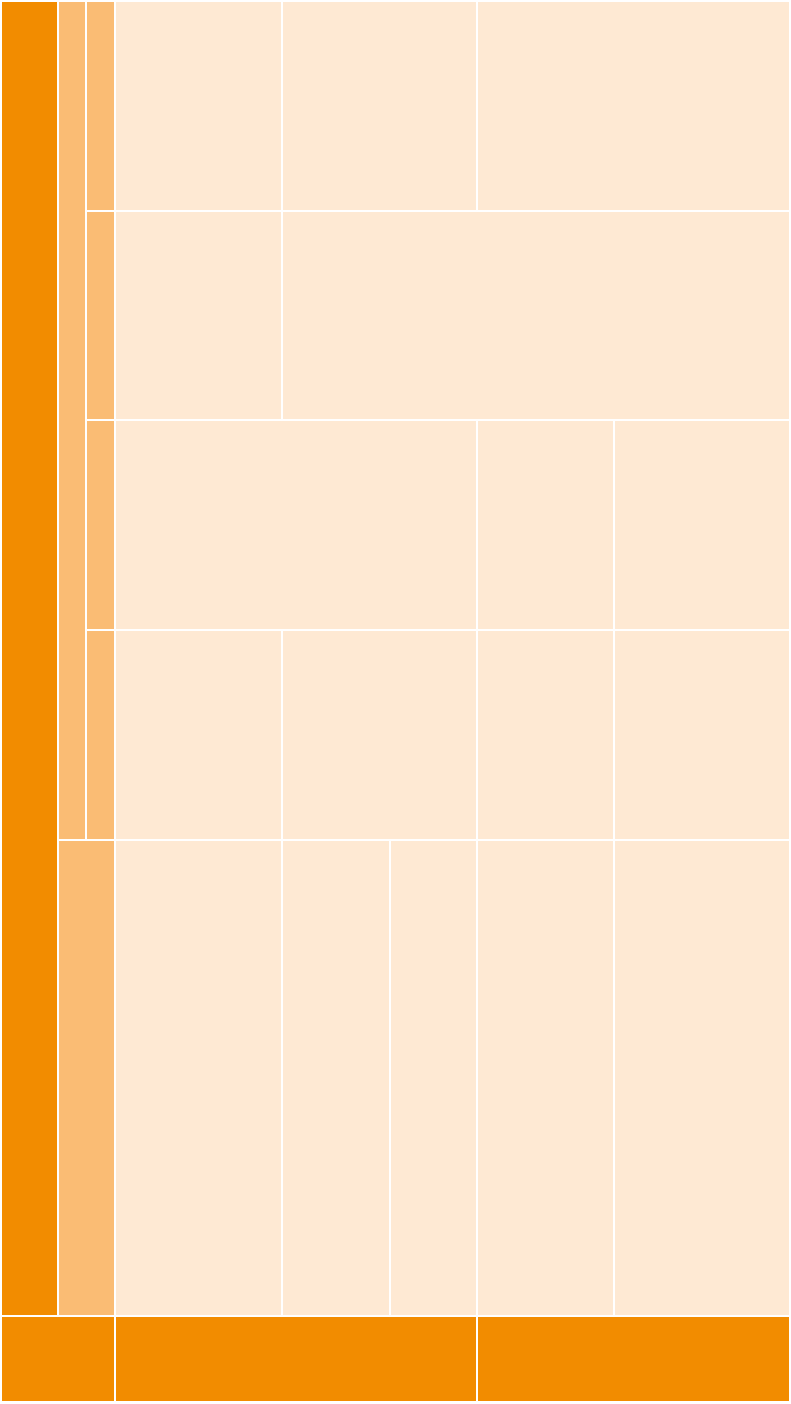

POSTGRADUATE NATURAL SCIENCES FICTIONAL 39

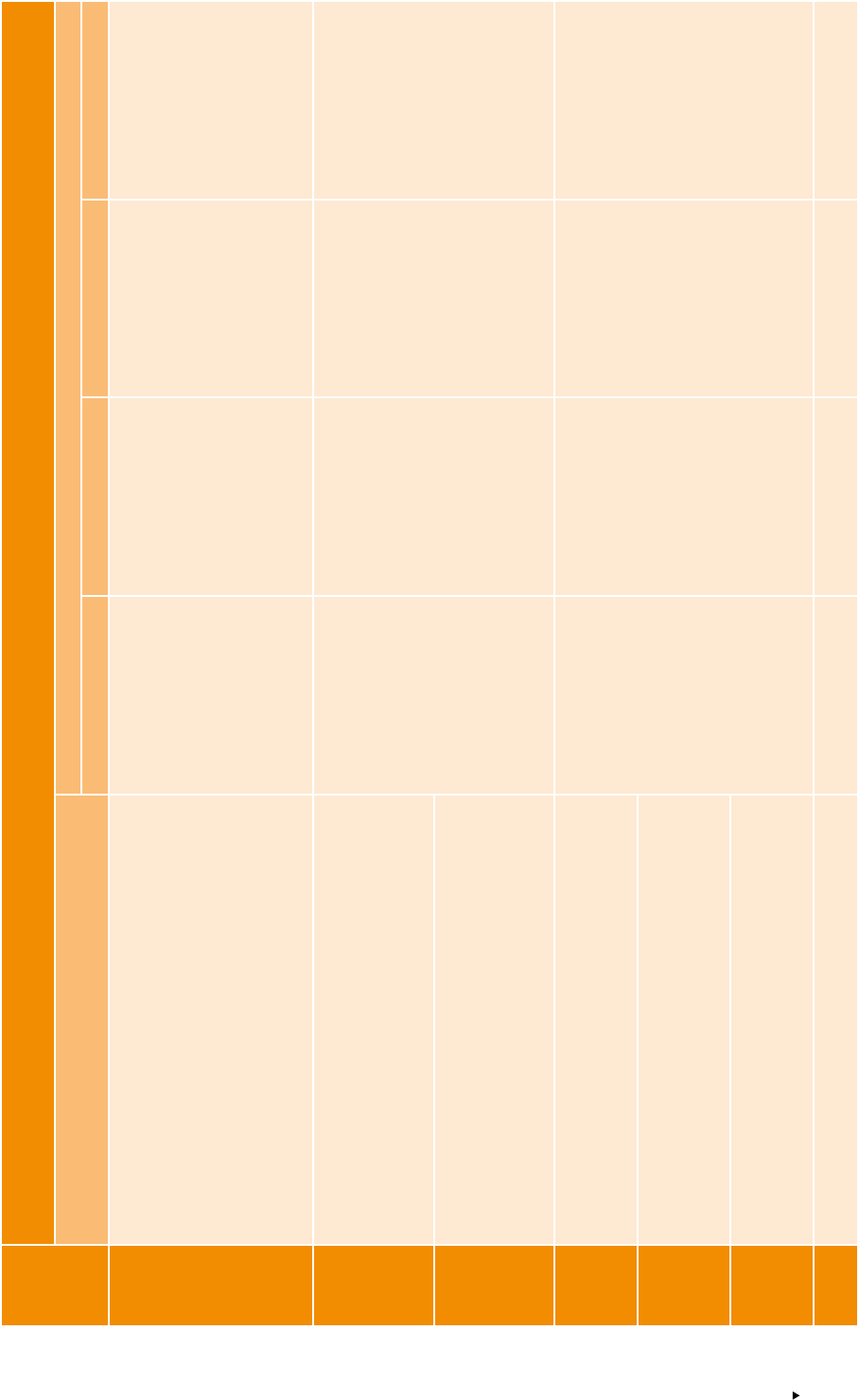

FIGURE 8 A PLURILINGUAL PROFICIENCY PROFILE WITH FEWER CATEGORIES 40

FIGURE 9 A PROFICIENCY PROFILE OVERALL PROFICIENCY IN ONE LANGUAGE 40

FIGURE 10 A PLURILINGUAL PROFICIENCY PROFILE ORAL COMPREHENSION ACROSS LANGUAGES 40

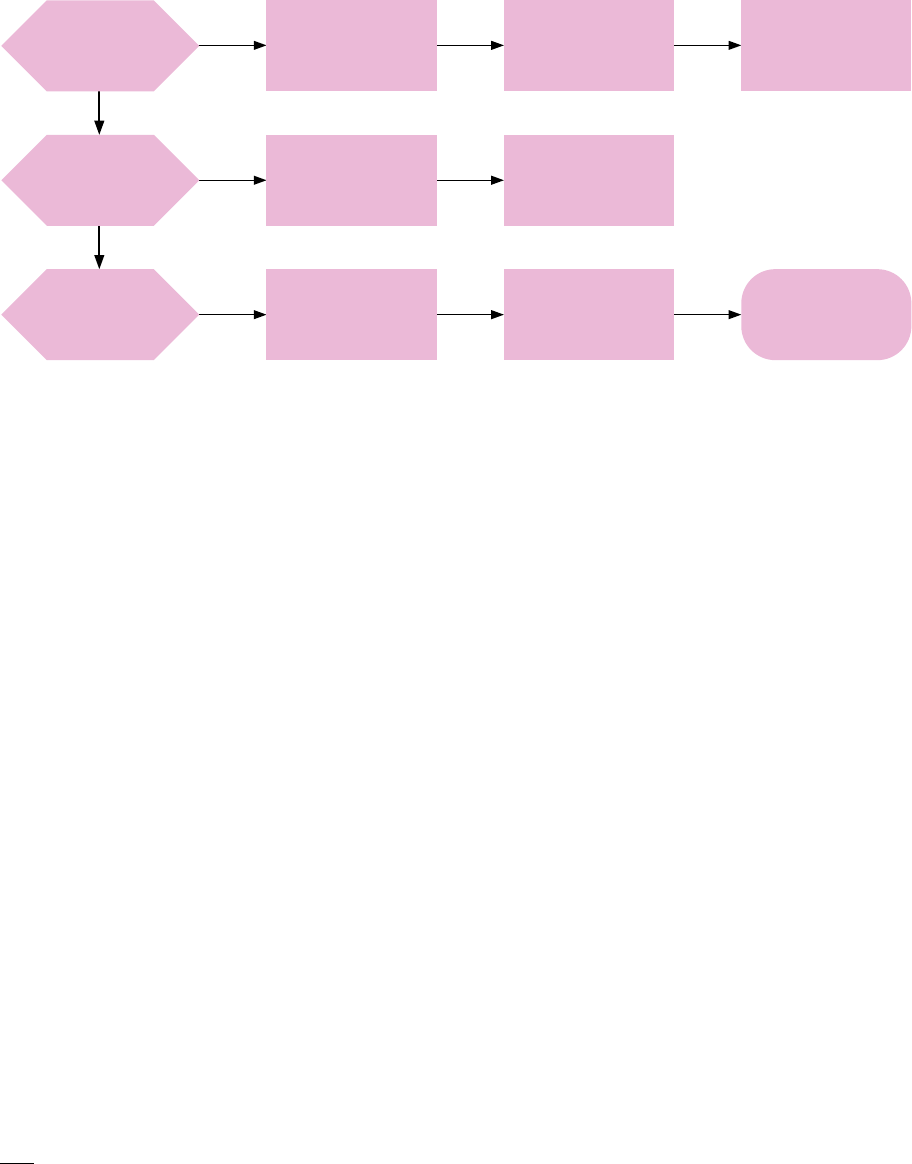

FIGURE 11 RECEPTION ACTIVITIES AND STRATEGIES 47

FIGURE 12 PRODUCTION ACTIVITIES AND STRATEGIES 61

FIGURE 13 INTERACTION ACTIVITIES AND STRATEGIES 71

FIGURE 14 MEDIATION ACTIVITIES AND STRATEGIES 90

FIGURE 15 PLURILINGUAL AND PLURICULTURAL COMPETENCE 123

FIGURE 16 COMMUNICATIVE LANGUAGE COMPETENCES 129

FIGURE 17 SIGNING COMPETENCES 144

FIGURE 18 DEVELOPMENT DESIGN OF YOUNG LEARNER PROJECT 244

FIGURE 19 MULTIMETHOD DEVELOPMENTAL RESEARCH DESIGN 249

FIGURE 20 THE PHASES OF THE SIGN LANGUAGE PROJECT 254

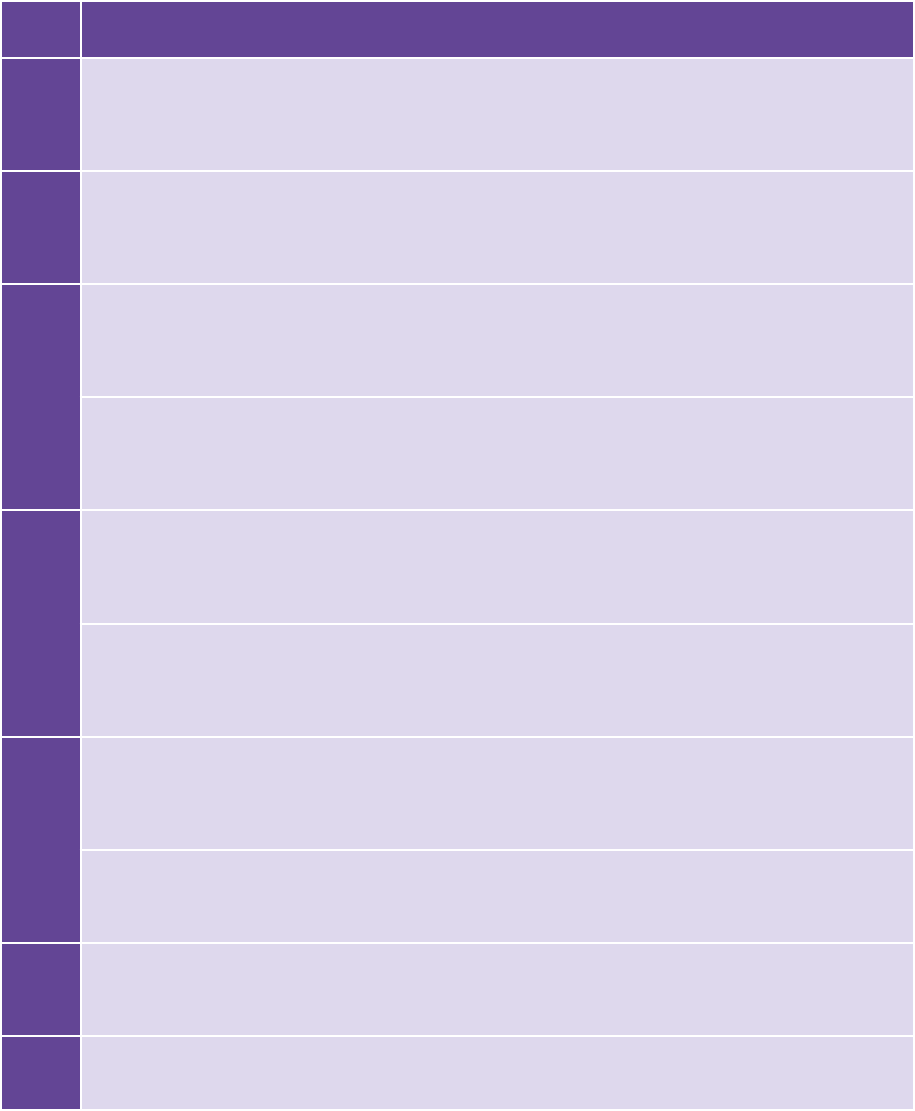

LIST OF TABLES

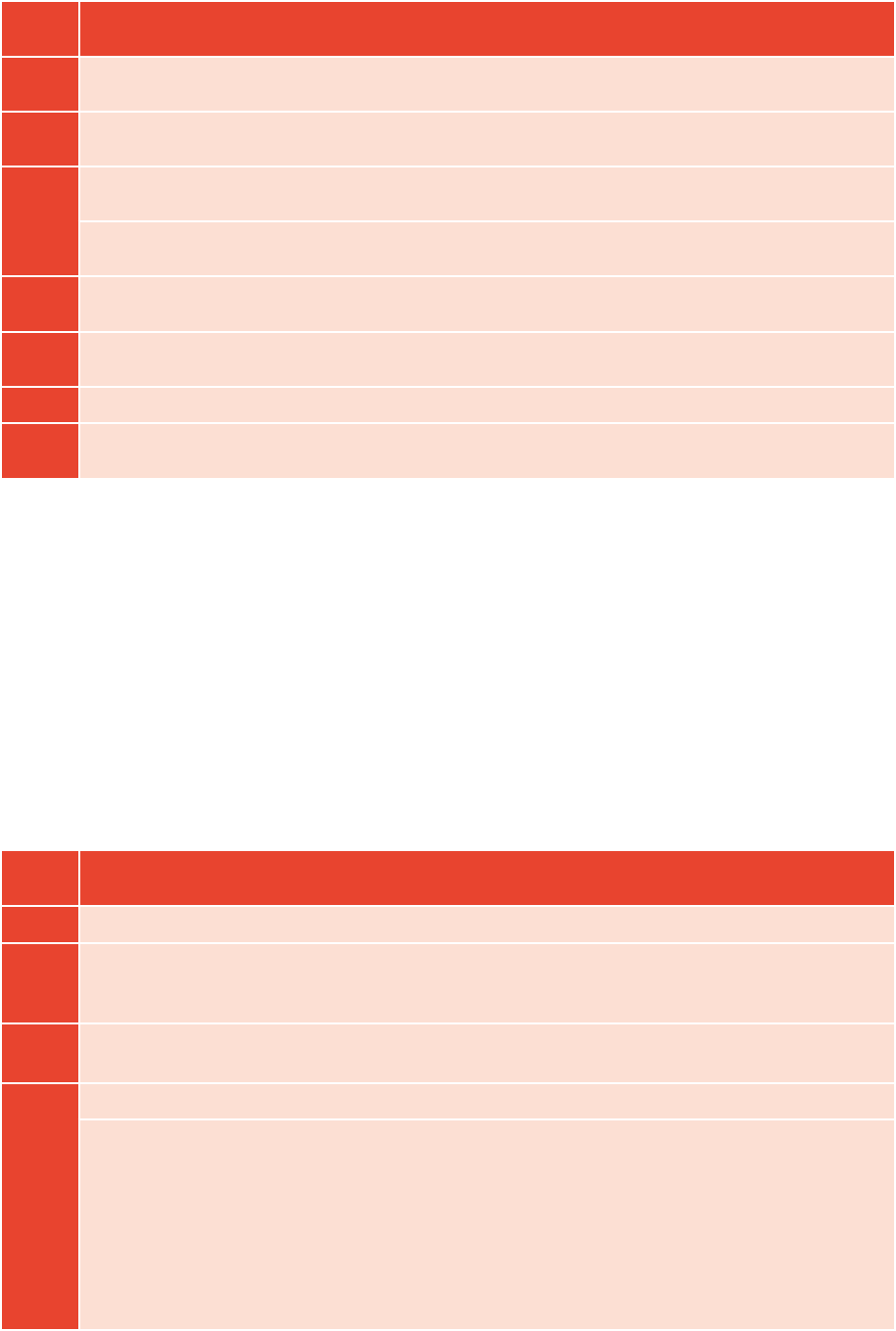

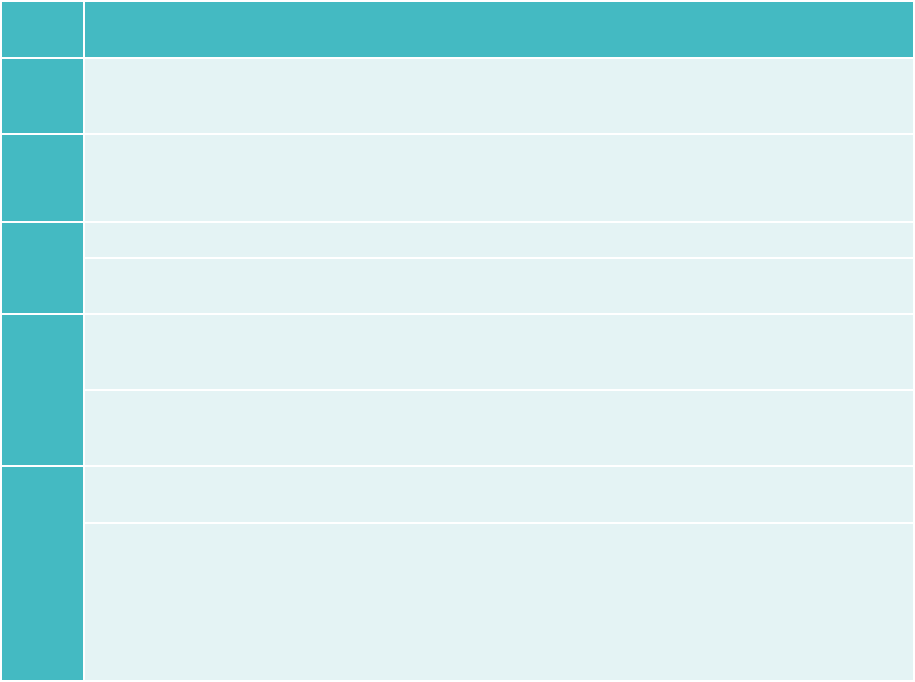

TABLE 1 THE CEFR DESCRIPTIVE SCHEME AND ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTORS: UPDATES AND ADDITIONS 23

TABLE 2 SUMMARY OF CHANGES TO THE ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTORS 24

TABLE 3 MACROFUNCTIONAL BASIS OF CEFR CATEGORIES FOR COMMUNICATIVE LANGUAGE ACTIVITIES 33

TABLE 4 COMMUNICATIVE LANGUAGE STRATEGIES IN THE CEFR 35

TABLE 5 THE DIFFERENT PURPOSES OF DESCRIPTORS 44

Page 11

1. www.coe.int/lang-cefr.

2. www.coe.int/en/web/portfolio.

FOREWORD

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)

1

is one of the

best-known and most used Council of Europe policy instruments. Through the European Cultural Convention

50 European countries commit to encouraging “the study by its own nationals of the languages, history and

civilisation” of other European countries. The CEFR has played and continues to play an important role in making

this vision of Europe a reality.

Since its launch in 2001, the CEFR, together with its related instrument for learners, the European Language

Portfolio (ELP),

2

has been a central feature of the Council of Europe’s intergovernmental programmes in the eld

of education, including their initiatives to promote the right to quality education for all. Language education

contributes to Council of Europe’s core mission “to achieve a greater unity between its members” and is

fundamental to the eective enjoyment of the right to education and other individual human rights and the

rights of minorities as well as, more broadly, to developing and maintaining a culture of democracy.

The CEFR is intended to promote quality plurilingual education, facilitate greater social mobility and stimulate

reection and exchange between language professionals for curriculum development and in teacher education.

Furthermore the CEFR provides a metalanguage for discussing the complexity of language prociency for all

citizens in a multilingual and intercultural Europe, and for education policy makers to reect on learning objectives

and outcomes that should be coherent and transparent. It has never been the intention that the CEFR should

be used to justify a gate-keeping function of assessment instruments.

The Council of Europe hopes that the development in this publication of areas such as mediation, plurilingual/

pluricultural competence and signing competences will contribute to quality inclusive education for all, and to

the promotion of plurilingualism and pluriculturalism.

Snežana Samardžić-Marković

Council of Europe

Director General for Democracy

Page 13

PREFACE WITH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

3. www.coe.int/lang-cefr.

4. www.coe.int/lang-platform.

5. Beacco J.-C. et al. (2016a), Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education, Council

of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, available at https://rm.coe.int/16806ae621.

6. Beacco J.-C. et al. (2016b), A handbook for curriculum development and teacher education: the language dimension in all subjects, Council

of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, available at https://rm.coe.int/16806af387.

7. Beacco J.-C. and Byram M. (2007), “From linguistic diversity to plurilingual education: guide for the development of language education

policies in Europe”, Language Policy Division, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, available at https://rm.coe.int/16802fc1c4.

8. www.coe.int/en/web/lang-migrants/ocials-texts-and-guidelines.

9. www.coe.int/t/dg4/autobiography/default_en.asp.

10. Council of Europe (2018), Reference framework of competences for democratic culture, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, available

at https://go.coe.int/mWYUH, accessed 6 March 2020.

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR) was published

in 2001 (the European Year of Languages) after a comprehensive process of drafting, piloting and consultation.

The CEFR has contributed to the implementation of the Council of Europe’s language education principles,

including the promotion of reective learning and learner autonomy.

A comprehensive set of resources has been developed around the CEFR since its publication in order to support

implementation and, like the CEFR itself, these resources are presented on the Council of Europe’s CEFR website.

3

Building on the success of the CEFR and other projects a number of policy documents and resources that

further develop the underlying educational principles and objectives of the CEFR are also available, not only for

foreign/second languages but also for the languages of schooling and the development of curricula to promote

plurilingual and intercultural education. Many of these are available on the Platform of resources and references

for plurilingual and intercultural education,

4

for example:

f Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education;

5

f A handbook for curriculum development and teacher education: the language dimension in all subjects;

6

f

“From linguistic diversity to plurilingual education: guide for the development of language education

policies in Europe”;

7

Others are available separately:

f policy guidelines and resources for the linguistic integration of adult migrants;

8

f guidelines for intercultural education and an autobiography of intercultural encounters;

9

f Reference framework of competences for democratic culture.

10

However, regardless of all this further material provided, the Council of Europe frequently received requests to

continue to develop aspects of the CEFR, particularly the illustrative descriptors of second/foreign language

prociency. Requests were made asking the Council of Europe to complement the illustrative scales published

in 2001 with descriptors for mediation, reactions to literature and online interaction, to produce versions for

young learners and for signing competences, and to develop more detailed coverage in the descriptors for A1

and C levels.

Much work done by other institutions and professional bodies since the publication of the CEFR has conrmed

the validity of the initial research conducted under a Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) research project

by Brian North and Günther Schneider. To respond to the requests received and in keeping with the open,

dynamic character of the CEFR, the Education Policy Division (Language Policy Programme) therefore resolved

to build on the widespread adoption and use of the CEFR to produce an extended version of the illustrative

descriptors that replaces the ones contained in the body of the CEFR 2001 text. For this purpose, validated and

calibrated descriptors were generously oered to the Council of Europe by a number of institutions in the eld

of language education.

For mediation, an important concept introduced in the CEFR that has assumed even greater importance with

the increasing linguistic and cultural diversity of our societies, however, no validated and calibrated descriptors

existed. The development of descriptors for mediation was, therefore, the longest and most complex part of

the project. Descriptor scales are here provided for mediating a text, for mediating concepts and for mediating

communication, as well as for the related mediation strategies and plurilingual/pluricultural competences.

Page 14 3 CEFR – Companion volume

As part of the process of further developing the descriptors, an eort was made to make them modality-inclusive.

The adaptation of the descriptors in this way is informed by the ECML’s pioneering PRO-Sign project. In addition,

illustrative descriptor scales specically for signing competences are provided, again informed by SNSF research

project No. 100015_156592.

First published online in 2018 as the “CEFR Companion Volume with New Descriptors”, this update to the CEFR

therefore represents another step in a process that has been pursued by the Council of Europe since 1964. In

particular, the descriptors for new areas represent an enrichment of the original descriptive apparatus. Those

responsible for curriculum planning for foreign languages and languages of schooling will nd further guidance

on promoting plurilingual and intercultural education in the guides mentioned above. In addition to the extended

illustrative descriptors, this publication contains a user-friendly explanation of the aims and main principles of

the CEFR, which the Council of Europe hopes will help increase awareness of the CEFR’s messages, particularly

in teacher education. For ease of consultation, this publication contains links and references to the 2001 edition,

which remains a valid reference for its detailed chapters.

The fact that this edition of the CEFR descriptors takes them beyond the area of modern language learning to

encompass aspects relevant to language education across the curriculum was overwhelmingly welcomed in

the extensive consultation process undertaken in 2016-17. This reects the increasing awareness of the need

for an integrated approach to language education across the curriculum. Language teaching practitioners

particularly welcomed descriptors concerned with online interaction, collaborative learning and mediating

text. The consultation also conrmed the importance that policy makers attach to the provision of descriptors

for plurilingualism/pluriculturalism. This is reected in the Council of Europe’s recent initiative to develop

competences for democratic culture,

11

such as valuing cultural diversity and openness to cultural otherness and

to other beliefs, worldviews and practices.

This publication owes much to the contributions of members of the language teaching profession across

Europe and beyond. It was authored by Brian North, Tim Goodier (Eurocentres Foundation) and Enrica Piccardo

(University of Toronto/Université Grenoble-Alpes). The chapter on signing competences was produced by Jörg

Keller (Zurich University of Applied Sciences).

Publication has been assisted by a project follow-up advisory group consisting of: Marisa Cavalli, Mirjam Egli

Cuenat, Neus Figueras Casanovas, Francis Goullier, David Little, Günther Schneider and Joseph Sheils.

In order to ensure complete coherence and continuity with the CEFR scales published in 2001, the Council of

Europe asked the Eurocentres Foundation to once again take on responsibility for co-ordinating the further

development of the CEFR descriptors, with Brian North co-ordinating the work. The Council of Europe wishes to

express its gratitude to Eurocentres for the professionalism and reliability with which the work has been carried out.

The entire process of updating and extending the illustrative descriptors took place in ve stages or sub-projects:

Stage 1: Filling gaps in the illustrative descriptor scales published in 2001with materials then available (2014-15)

Authoring Group: Brian North, Tunde Szabo, Tim Goodier (Eurocentres Foundation)

Sounding Board: Gilles Breton, Hanan Khalifa, Christine Tagliante, Sauli Takala

Consultants: Coreen Docherty, Daniela Fasoglio, Neil Jones, Peter Lenz, David Little, Enrica Piccardo,

Günther Schneider, Barbara Spinelli, Maria Stathopoulou, Bertrand Vittecoq

Stage 2: Developing descriptor scales for areas missing in the 2001 set, in particular for mediation (2014-16)

Authoring Group: Brian North, Tim Goodier, Enrica Piccardo, Maria Stathopoulou

Sounding Board: Gilles Breton, Coreen Docherty, Hanan Khalifa, Ángeles Ortega, Christine Tagliante,

Sauli Takala

Consultants (at meetings in June 2014, June 2015 and/or June 2016): Marisa Cavalli, Daniel Coste, Mirjam

Egli Ceunat, Gudrun Erickson, Daniela Fasoglio, Vincent Folny, Manuela Ferreira Pinto, Glyn Jones, Neil

Jones, Peter Lenz, David Little, Gerda Piribauer, Günther Schneider, Joseph Sheils, Belinda Steinhuber,

Barbara Spinelli, Bertrand Vittecoq

11. https://go.coe.int/mWYUH

Preface with acknowledgements Page 15

Consultants (at a meeting in June 2016 only): Sarah Breslin, Mike Byram, Michel Candelier, Neus Figueras

Casanovas, Francis Goullier, Hanna Komorowska, Terry Lamb, Nick Saville, Maria Stoicheva, Luca Tomasi

Stage 3: Developing a new scale for phonological control (2015-16)

Authoring Group: Enrica Piccardo, Tim Goodier

Sounding Board: Brian North, Coreen Docherty

Consultants: Sophie Deabreu, Dan Frost, David Horner, Thalia Isaacs, Murray Munro

Stage 4: Developing descriptors for signing competences (2015-19)

Authoring Group: Jörg Keller, Petrea Bürgin, Aline Meili, Dawei Ni

Sounding Board: Brian North, Curtis Gautschi, Jean-Louis Brugeille, Kristin Snoddon

Consultants: Patty Shores, Tobias Haug, Lorraine Leeson, Christian Rathmann, Beppie van den Bogaerde

Stage 5: Collating descriptors for young learners (2014-16)

Authoring Group: Tunde Szabo (Eurocentres Foundation)

Sounding Board: Coreen Docherty, Tim Goodier, Brian North

Consultants: Angela Hasselgreen, Eli Moe

The Council of Europe wishes to thank the following institutions and projects for kindly making their validated

descriptors available:

f ALTE (Association of Language Testers in Europe) Can do statements

f AMKKIA project (Finland) Descriptors for grammar and vocabulary

f Cambridge Assessment English BULATS Summary of Typical Candidate Abilities

Common Scales for Speaking and for Writing

Assessment Scales for Speaking and for Writing

f CEFR-J project Descriptors for secondary school learners

f Eaquals Eaquals bank of CEFR-related descriptors

f English Prole Descriptors for the C level

f Lingualevel/IEF (Swiss) project Descriptors for secondary school learners

f Pearson Education Global Scale of English (GSE)

The Council of Europe would also like to thank:

Pearson Education for kindly validating some 50 descriptors that were included from non-calibrated sources,

principally from the Eaquals’ bank and the late John Trim’s translation of descriptors for the C levels in Prole

Deutsch.

The Research Centre for Language Teaching, Testing and Assessment, National and Kapodistrian University of

Athens (RCeL) for making available descriptors from the Greek Integrated Foreign Languages Curriculum.

Cambridge Assessment English, in particular Coreen Docherty, for the logistical support oered over a period of

six months to the project, without which large-scale data collection and analysis would not have been feasible.

The Council of Europe also wishes to gratefully acknowledge the support from the institutions listed at the end

of this section, who took part in the three phases of validation for the new descriptors, especially all those who

also assisted with piloting them.

Cambridge Assessment English and the European Language Portfolio authors for making their descriptors

available for the collation of descriptors for young learners.

The Swiss National Science Foundation and the Max Bircher Stiftung for funding the research and development

of the descriptors for signing competences.

12

12. SNSF research project 100015_156592: Gemeinsamer Europäischer Referenzrahmen für Gebärdensprachen: Empirie-basierte Grundlagen

für grammatische, pragmatische und soziolinguistische Deskriptoren in Deutschschweizer Gebärdensprache, conducted at the Zurich

University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW, Winterthur). The SNSF provided some €385000 for this research into signing competences.

Page 16 3 CEFR – Companion volume

The PRO-Sign project team (European Centre for Modern Languages, ECML) for their assistance in nalising the

descriptors for signing competences and in adapting the other descriptors for modality inclusiveness.

13

The Department of Deaf Studies and Sign Language Interpreting at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin for undertaking

the translation of the whole document, including all the illustrative descriptors, into International Sign.

The following readers, whose comments on an early version of the text on key aspects of the CEFR for learning,

teaching and assessment greatly helped to structure it appropriately for readers with dierent degrees of

familiarity with the CEFR: Sezen Arslan, Danielle Freitas, Angelica Galante, İsmail Hakkı Mirici, Nurdan Kavalki,

Jean-Claude Lasnier, Laura Muresan, Funda Ölmez.

Organisations, in alphabetical order, that facilitated the recruitment of institutes for the validation of the

descriptors for mediation, online interaction, reactions to literature and plurilingual/pluricultural competence:

f Cambridge Assessment English

f CERCLES: European Confederation of Language Centres in Higher Education

f CIEP: Centre international d’études pédagogiques

f EALTA: European Association for Language Testing and Assessment

f Eaquals: Evaluation and Accreditation of Quality in Language Services

f FIPLV: International Federation of Language Teaching Associations

f Instituto Cervantes

f NILE (Norwich Institute for Language Education)

f UNIcert

Institutes (organised in alphabetical order by country) that participated between February and November 2015

in the validation of the descriptors for mediation, online interaction, reactions to literature and plurilingual/

pluricultural competence, and/or assisted in initial piloting. The Council of Europe also wishes to thank the many

individual participants, all of whose institutes could not be included here.

Algeria

Institut Français d’Alger

Argentina

Academia Argüello, Córdoba St Patrick’s School, Córdoba

La Asociación de Ex Alumnos del Profesorado en Lenguas

Vivas Juan R. Fernández

Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata

National University of Córdoba

Austria

BBS (Berufsbildende Schule), Rohrbach Institut Français d’Autriche-Vienne

BG/BRG (Bundesgymnasium/Bundesrealgymnasium),

Hallein

International Language Centre of the University of

Innsbruck

CEBS (Center für berufsbezogene Sprachen des bmbf),

Vienna

LTRGI (Language Testing Research Group Innsbruck),

School of Education, University of Innsbruck

Federal Institute for Education Research (BIFIE), Vienna Language Centre of the University of Salzburg

HBLW Linz-Landwiedstraße Pädagogische Hochschule Niederösterreich

HLW (Höhere Lehranstalt für wirtschaftliche Berufe)

Ferrarischule, Innsbruck

Bolivia

Alliance Française de La Paz

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Anglia V Language School, Bijeljina Institut Français de Bosnie-Herzégovine

Brazil

Alliance Française Instituto Cervantes do Recife

Alliance Française de Curitiba

Bulgaria

AVO Language and Examination Centre, Soa Soa University St. Kliment Ohridski

13. See www.ecml.at/ECML-Programme/Programme2012-2015/ProSign/tabid/1752/Default.aspx. Project team: Tobias Haug, Lorraine

Leeson, Christian Rathmann, Beppie van den Bogaerde.

Preface with acknowledgements Page 17

Cameroon

Alliance Française de Bamenda Institut Français du Cameroun, Yaoundé

Canada

OISE (Ontario Institute for Studies in Education), University

of Toronto

Chile

Alliance Française de La Serena

China

Alliance Française de Chine Heilongjiang University

China Language Assessment, Beijing Foreign Studies

University

The Language Training and Testing Center, Taipei

Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, School of

Interpreting and Translation Studies

Tianjin Nankai University

Colombia

Alliance Française de Bogota Universidad Surcolombiana

Croatia

University of Split X. Gimnazija “Ivan Supek”

Croatian Defence Academy, Zagreb Ministry of Science, Education and Sports

Cyprus

Cyprus University of Technology University of Cyprus

Czech Republic

Charles University, Prague (Institute for Language and

Preparatory Studies)

National Institute of Education

Masaryk University Language Centre, Brno University of South Bohemia

Egypt

Institut Français d’Egypt Instituto Cervantes de El Cairo

Estonia

Foundation Innove, Tallinn

Finland

Aalto University Tampere University of Applied Sciences

Häme University of Applied Sciences Turku University

Language Centre, University of Tampere University of Eastern Finland

Matriculation Examination Board University of Helsinki Language Centre

National Board of Education University of Jyväskylä

France

Alliance Française Crea-langues, France

Alliance Française de Nice Eurocentres Paris

Alliance française Paris Ile-de-France France Langue

British Council, Lyon French in Normandy

CAVILAM (Centre d’Approches Vivantes des Langues et

des Médias) – Alliance Française

ILCF (Institut de Langue et de Culture Françaises), Lyon

CIDEF (Centre international d’études françaises),

Université catholique de l’Ouest

INFREP (Institute National Formation Recherche Education

Permanente)

CIEP (Centre international d’études pédagogiques) International House Nice

CLV (Centre de langues vivantes), Université

Grenoble-Alpes

ISEFE (Institut Savoisien d’Études Françaises pour

Étrangers)

Collège International de Cannes Université de Franche-Comté

Germany

Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Englisch an Gesamtschulen Technische Hochschule Wildau

elc-European Language Competence, Frankfurt Technische Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu

Braunschweig (Sprachenzentrum)

Frankfurt School of Finance & Management Technische Universität Darmstadt

Fremdsprachenzentrum der Hochschulen im Land

Bremen, Bremen University

Technische Universität München (Sprachenzentrum)

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (Zentrale Einrichtung

für Sprachen und Schlüsselqualikationen)

telc gGmbH Frankfurt

Goethe-Institut München Universität Freiburg (Sprachlehrinstitut)

Institut français d’Allemagne Universität Hohenheim (Sprachenzentrum)

Language Centre, Neu-Ulm University of Applied Sciences

(HNU)

Universität Leipzig (Sprachenzentrum)

Page 18 3 CEFR – Companion volume

Instituto Cervantes de Munich Universität Passau (Sprachenzentrum)

Institut für Qualitätsentwicklung

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Universität Regensburg (Zentrum für Sprache und

Kommunikation)

Justus-Liebig Universität Giessen (Zentrum für

fremdsprachliche und berufsfeldorientierte

Kompetenzen)

Universität Rostock (Sprachenzentrum)

Pädagogische Hochschule Heidelberg Universität des Saarlandes (Sprachenzentrum)

Pädagogische Hochschule Karlsruhe University Language Centers in Berlin and Brandenburg

Ruhr-Universität Bochum, ZFA (Zentrum für

Fremdsprachenausbildung )

VHS Siegburg

Sprachenzentrum, Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt

(Oder)

Greece

Bourtsoukli Language Centre RCeL: National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Hellenic American University in Athens Vagionia Junior High School, Crete

Hungary

ELTE ONYC ECL Examinations, University of Pécs

Eötvös Lorand University Tanárok Európai Egyyesülete, AEDE

Euroexam University of Debrecen

Budapest Business School University of Pannonia

Budapest University of Technology and Economics

India

ELT Consultants Fluency Center, Coimbatore

Ireland

Alpha College, Dublin NUI Galway

Galway Cultural Institute Trinity College Dublin

Italy

Accento, Martina Franca, Apulia International House, Palermo

AISLi (Associazione Italiana Scuola di Lingue) Istituto Comprensivo di Campli

Alliance Française Istituto Monti, Asti

Bennett Languages, Civitavecchia Liceo Scientico “Giorgio Spezia”, Domodossola

British School of Trieste Padova University Language Centre

British School of Udine Pisa University Language Centre

Centro Lingue Estere Arma dei Carabinieri Servizio Linguistico di Ateneo, Università Cattolica del

Sacro Cuore,Milano

Centro Linguistio di Ateneo – Università di Bologna Università degli Studi Roma Tre

Centro Linguistico di Ateneo di Trieste Università degli Studi di Napoli “Parthenope”/I.C. “Nino

Cortese”, Casoria, Naples

CVCL (Centro per la Valutazione e le Certicazioni

linguistiche) – Università per Stranieri di Perugia

Università degli Studi di Parma

Free University of Bolzano, Language Study Unit University of Bologna

Globally Speaking, Rome Centro Linguistico di Ateneo, Università della Calabria

Institut Français de Milan University of Brescia

Institute for Educational Research/LUMSA University,

Rome

Università per Stranieri di Siena

Japan

Alliance Française du Japon Japan School of Foreign Studies, Osaka University

Institut Français du Japon Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan

Latvia

Baltic International Academy, Department of Translation

and Interpreting

University of Latvia

Lebanon

Institut Français du Liban

Lithuania

Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences Vilnius University

Ministry of Education and Science

Luxembourg

Ministry of Education, Children and Youth University of Luxembourg

Mexico

University of Guadalajara

Preface with acknowledgements Page 19

Morocco

Institut Français de Maroc

Netherlands

Institut Français des Pays-Bas SLO (Netherlands Institute for curriculum development)

Cito University of Groningen, Language Centre

New Zealand

LSI (Language Studies International) Worldwide School of English

North Macedonia

AAB University Language Center, South East European University

Elokventa Language Centre MAQS (Macedonian Association for Quality Language

Services), Queen Language School

Norway

Department of Teacher Education and School Research,

University of Oslo

Vox – Norwegian Agency for Lifelong Learning

University of Bergen

Peru

Alliance Française au Peru USIL (Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola)

Poland

British Council, Warsaw Jagiellonian Language Center, Jagiellonian University,

Kraków

Educational Research Institute, Warsaw LANG LTC Teacher Training Centre, Warsaw

Gama College, Kraków Poznan University of Technology, Poland

Instituto Cervantes, Kraków SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities,

Poland

Portugal

British Council, Lisbon IPG (Instituto Politécnico da Guarda)

Camões, Instituto da Cooperação e da Língua ISCAP – Instituto Superior de Contabilidade e

Administração do Porto, Instituto Politécnico do Porto

FCSH, NOVA University of Lisbon University of Aveiro

Romania

ASE (Academia de Studii Economice din Bucuresti) Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiesti

Institut Français de Roumanie Universitatea Aurel Vlaicu din Arad

LINGUA Language Centre of Babe-Bolyai,

UniversityCluj-Napoca

Russia

Globus International Language Centres Nizhny Novgorod Linguistics University

Lomonosov Moscow State University Samara State University

MGIMO (Moscow State Institute of International Relations) St Petersburg State University

National Research University Higher Schools of

Economics, Moscow

Saudi Arabia

ELC (English Language Center ), Taibah University,

Madinah

National Center for Assessment in Higher Education,

Riyadh

Senegal

Institut Français de Dakar

Serbia

Centre Jules Verne University of Belgrade

Institut Français de Belgrade

Slovakia

Trnava University

Slovenia

Državni izpitni center

Spain

Alliance Française en Espagne EOI de Villanueva-Don Benito, Extremadura

British Council, Madrid ILM (Instituto de Lenguas Modernas), Caceres

British Institute of Seville Institut Français d’Espagne

Centro de Lenguas, Universitat Politècnica de València Instituto Britanico de Sevilla S.A.

Consejería de Educación de la Junta de Andalucía Instituto de Lenguas Modernas de la Universidad de

Extremadura

Departament d’Ensenyament- Generalitat de Catalunya Lacunza International House, San Sebastián

Page 20 3 CEFR – Companion volume

EOI de Albacete Net Languages, Barcelona

EOI de Badajoz, Extremadura Universidad Antonio de Nebrija

EOI de Catalunya Universidad Europea de Madrid

EOI de Granada Universidad Internacional de La Rioja

EOI de La Coruña, Galicia Universidad Católica de València

EOI de Málaga, Málaga Universidad de Cantabria

EOI de Santa Cruz de Tenerife Universidad de Jaén

EOI de Santander Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla

EOI de Santiago de Compostela, Galicia Universidad Ramon Llull, Barcelona

EOI (Escola Ocial de Idiomas) de Vigo Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Sweden

Instituto Cervantes Stockholm University of Gothenburg

Switzerland

Bell Switzerland UNIL (Université de Lausanne), EPFL (École polytechnique

fédérale de Lausanne)

Eurocentres Lausanne Universität Fribourg

Sprachenzentrum der Universität Basel ZHAW (Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte

Wissenschaften), Winterthu

TLC (The Language Company) Internationa House

Zurich-Baden

Thailand

Alliance Française Bangkok

Turkey

Çağ University, Mersin ID Bilkent University, Ankara

Ege University Middle East Technical University, Ankara

Hacettepe University, Ankara Sabancı University, Istanbul

Uganda

Alliance Française de Kampala

Ukraine

Institute of Philology, Taras Shevchenko National

University of Kyiv

Sumy State University, Institute for Business Technologies

Odessa National Mechnikov University Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv

United Arab Emirates

Higher Colleges of Technology

United Kingdom

Anglia Examinations, Chichester College Pearson Education

Cambridge Assessment English School of Modern Languages and Culture, University of

Warwick

Eurocentres, Bournemouth Southampton Solent University, School of Business and

Law

Eurocentres, Brighton St Giles International London Central

Eurocentres, London Trinity College London

Experience English University of Exeter

Instituto Cervantes de Mánchester University of Hull

International Study and Language Institute, University of

Reading

University of Liverpool

Kaplan International College, London University of Westminster

NILE (Norwich Institute for Language Education) Westminster Professional Language Centre

United States of America

Alliance Française de Porto Rico ETS (Educational Testing Service)

Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments Purdue University

Columbia University, New York University of Michigan

Eastern Michigan University

Uruguay

Centro Educativo Rowan, Montevideo

Page 21

Chapter 1

14. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (2001), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

available at https://rm.coe.int/1680459f97.

INTRODUCTION

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)

14

is part of

the Council of Europe’s continuing work to ensure quality inclusive education as a right of all citizens. This update

to the CEFR, rst published online in 2018 in English and French as the “CEFR Companion Volume with New

Descriptors”, updates and extends the CEFR, which was published as a book in 2001 and which is available in

40 languages at the time of writing. With this new, user-friendly version, the Council of Europe responds to the

many comments that the 2001 edition was a very complex document that many language professionals found

dicult to access. The key aspects of the CEFR vision are therefore explained in Chapter 2, which elaborates the

key notions of the CEFR as a vehicle for promoting quality in second/foreign language teaching and learning

as well as in plurilingual and intercultural education. The updated and extended version of the CEFR illustrative

descriptors contained in this publication replaces the 2001 version of them.

Teacher educators and researchers will nd it worthwhile to follow links and/or references given in Chapter 2

“Key aspects of the CEFR for teaching and learning” in order to also consult the chapters of the 2001 edition on,

for example, full details of the descriptive scheme (CEFR 2001, Chapters 4 and 5). The updated and extended

illustrative descriptors include all those from the CEFR 2001. The descriptor scales are organised according to

the categories of the CEFR descriptive scheme. It is important to note that the changes and additions in this

publication do not aect the construct described in the CEFR, or its Common Reference Levels.

The CEFR in fact consists of far more than a set of common reference levels. As explained in Chapter 2, the CEFR

broadens the perspective of language education in a number of ways, not least by its vision of the user/learner

as a social agent, co-constructing meaning in interaction, and by the notions of mediation and plurilingual/

pluricultural competences. The CEFR has proved successful precisely because it encompasses educational values,

a clear model of language-related competences and language use, and practical tools, in the form of illustrative

descriptors, to facilitate the development of curricula and orientation of teaching and learning.

Page 22 3 CEFR – Companion volume

This publication is the product of a project of the Education Policy Division of the Council of Europe. The focus

in that project was to update the CEFR’s illustrative descriptors by:

f highlighting certain innovative areas of the CEFR for which no descriptor scales had been provided in the

set of descriptors published in 2001, but which have become increasingly relevant over the past 20 years,

especially mediation and plurilingual/pluricultural competence;

f building on the successful implementation and further development of the CEFR, for example by more

fully dening “plus levels” and a new “Pre-A1” level;

f responding to demands for more elaborate descriptions of listening and reading in existing scales, and

for descriptors for other communicative activities such as online interaction, using telecommunications,

and expressing reactions to creative texts (including literature);

f enriching description at A1, and at the C levels, particularly C2;

f adapting the descriptors to make them gender-neutral and “modality-inclusive” (and so applicable also to

sign languages), sometimes by changing verbs and sometimes by oering the alternatives “speaker/signer”.

In relation to the nal point above, the term “oral” is generally understood by the deaf community to include

signing. However, it is important to acknowledge that signing can transmit text that is closer to written than

oral text in many scenarios. Therefore, users of the CEFR are invited to make use of the descriptors for written

reception, production and interaction also for sign languages, as appropriate. And for this reason, the full set of

illustrative descriptors has been adapted with modality-inclusive formulations.

There are plans to make the full set of illustrative descriptors available in International Sign. Meanwhile, the ECML’s

PRO-Sign project

15

makes available videos in International Sign of many of the descriptors published in 2001.

This CEFR Companion volume presents an extended version of the illustrative descriptors:

f newly developed illustrative descriptor scales are introduced alongside existing ones;

f schematic tables are provided, which group together scales belonging to the same category (communi-

cative language activities or aspects of competence);

f a short rationale is presented for each scale, explaining the thinking behind the categorisation;

f descriptors that were developed and validated in the project, but not subsequently included in the illus-

trative descriptors, are presented in Appendix 8.

Small changes to formulations have been made to the descriptors to ensure that they are gender-neutral and

modality-inclusive. Any substantive changes made to descriptors published in 2001 are listed in Appendix 7.

The 2001 scales have been expanded with a selection of validated, calibrated descriptors from the institutions

listed in the preface and by descriptors developed, validated, calibrated and piloted during a 2014-17 project

to develop descriptors for mediation. The approach taken – both to the update of the descriptors published

in 2001 and in the mediation project – is described in Appendix 6. Examples of contexts of use for the new

illustrative descriptors for online interaction and for mediation activities, for the public, personal, occupational

and educational domains, are provided in Appendix 5.

In addition to the descriptors in this publication, a new collation of descriptors relevant for young learners,

16

put

together by the Eurocentres Foundation, is also available to assist with course planning and self-assessment.

Here, a dierent approach was adopted: descriptors in the extended illustrative descriptors that are relevant

for two age groups (7-10

17

and 11-15

18

) were selected. Then a collation was made of the adaptations of these

descriptors relevant to young learners, descriptors that appeared in the ELPs, complemented by assessment

descriptors for young learners generously oered by Cambridge Assessment English.

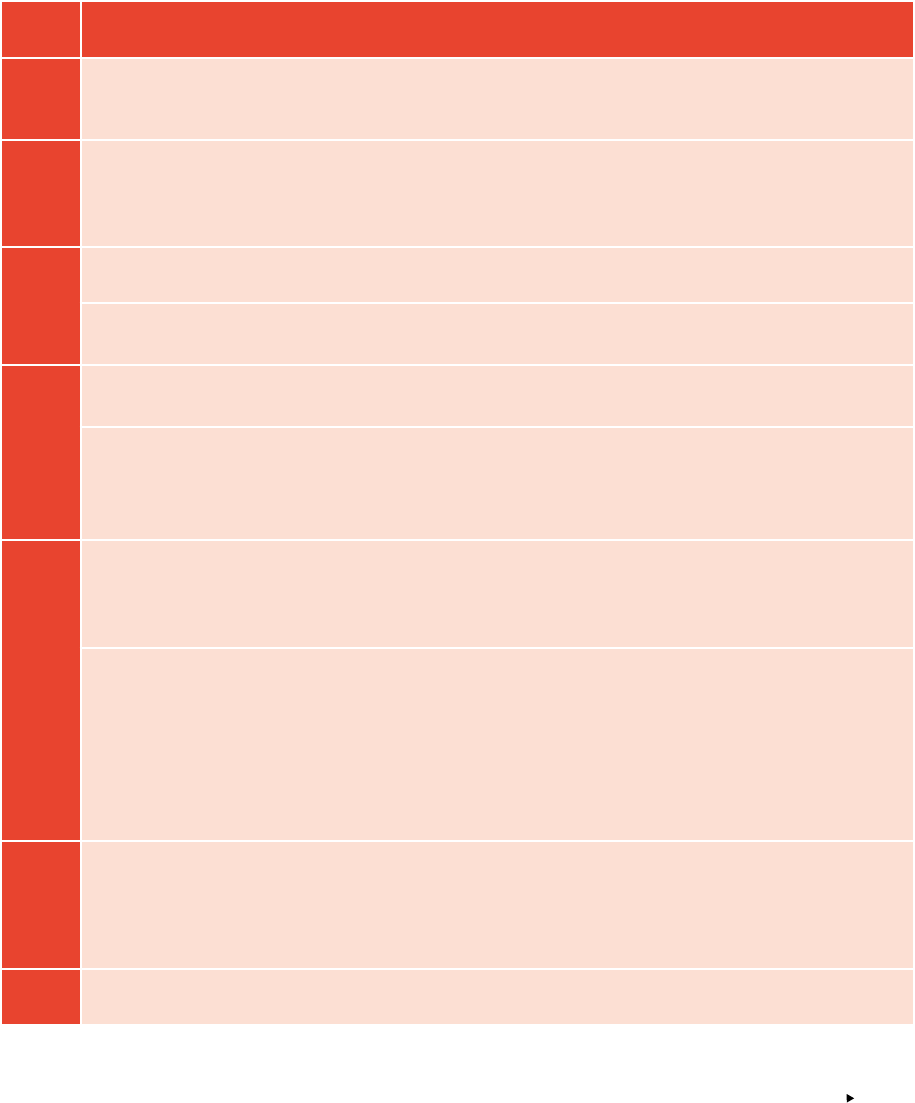

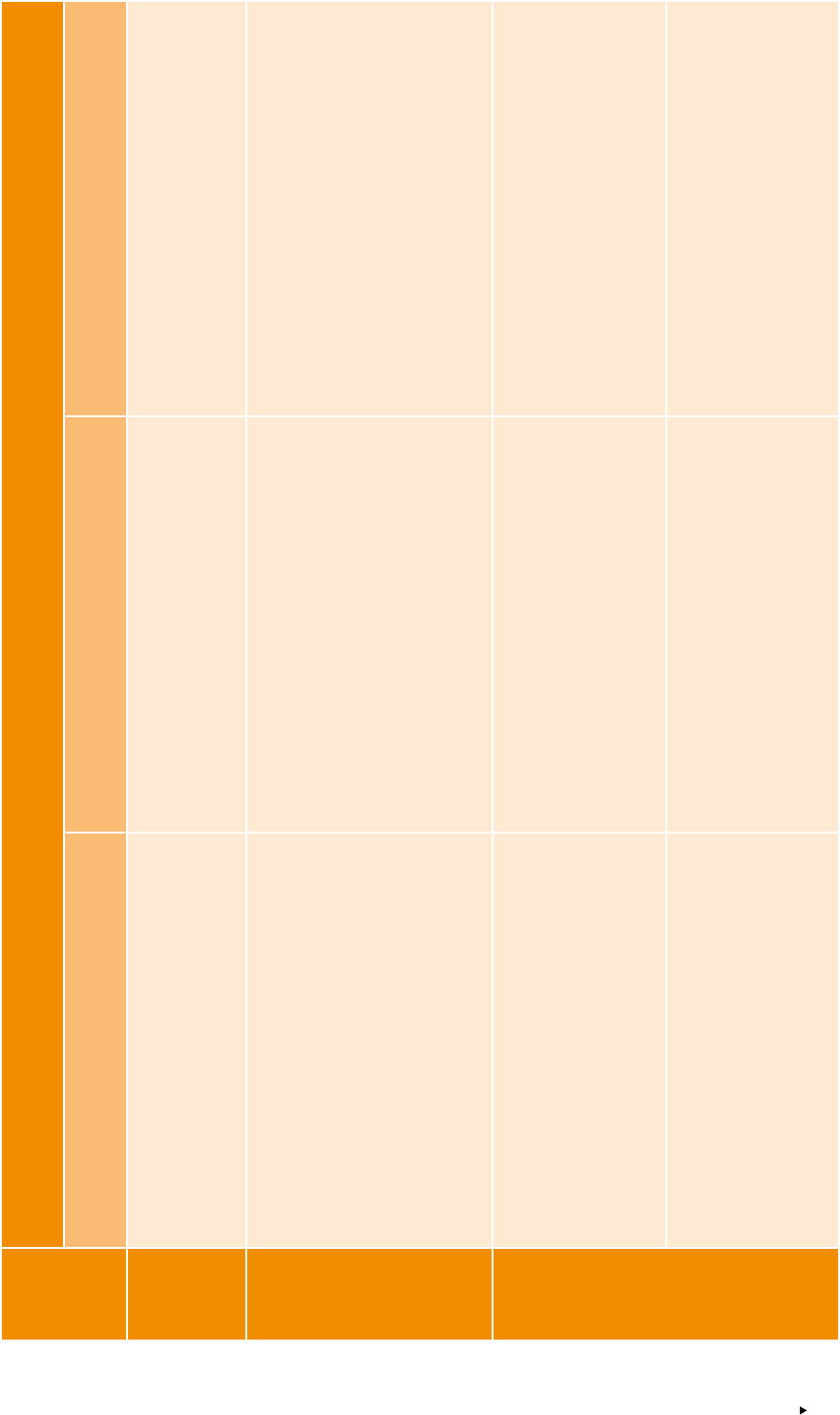

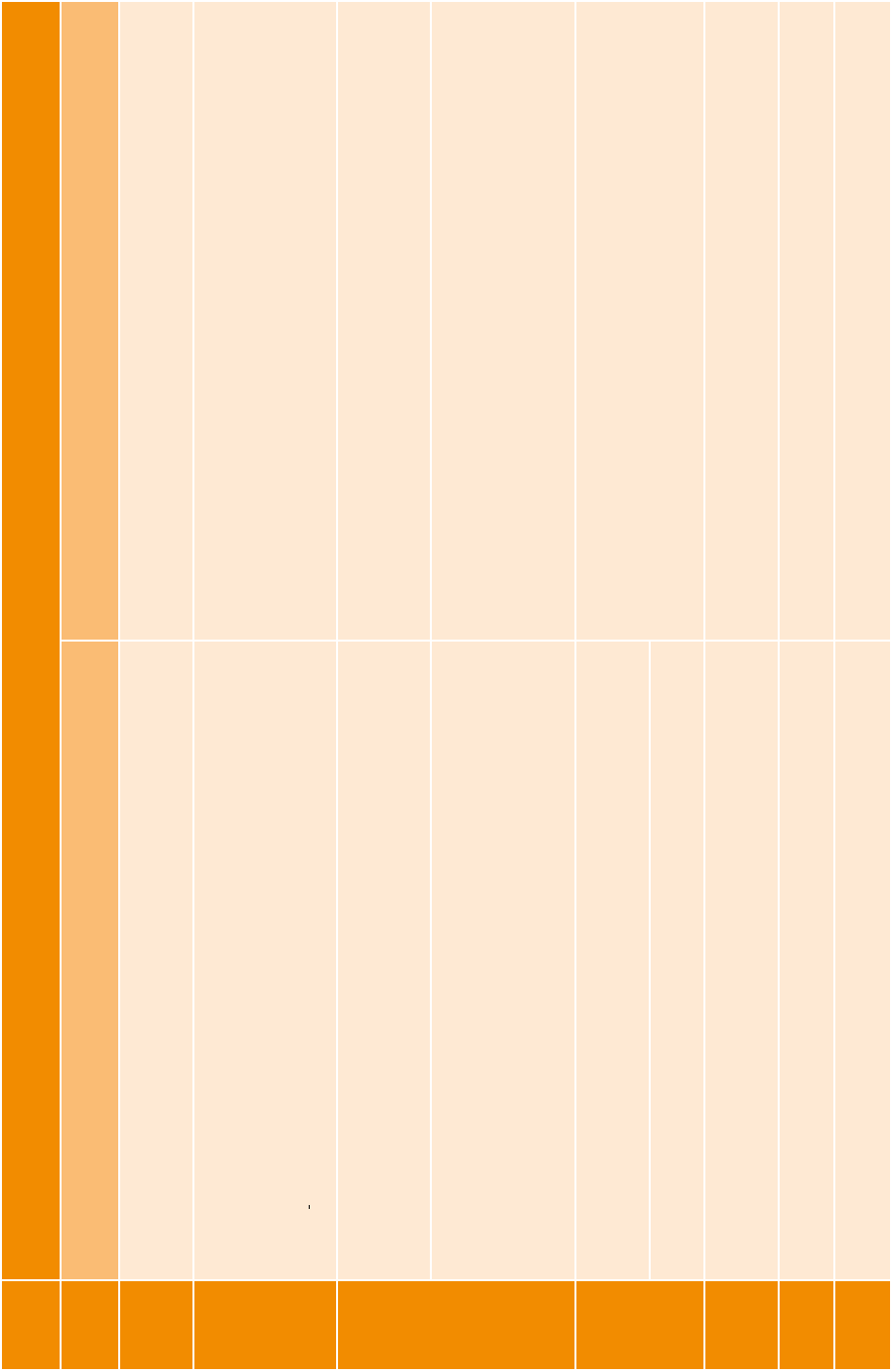

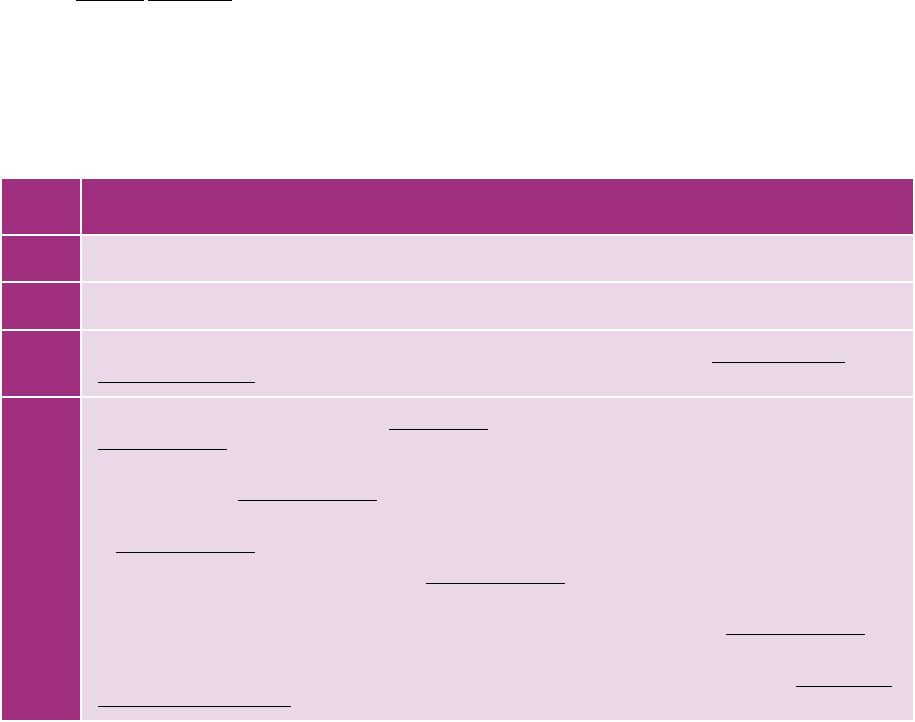

The relationship between the CEFR descriptive scheme, the illustrative descriptors published in 2001 and the

updates and additions provided in this publication is shown in Table 1. As can be seen, the descriptor scales

for reception are presented before those for production, although the latter appear rst in the 2001 CEFR text.

15. www.ecml.at/ECML-Programme/Programme2012-2015/ProSign/tabid/1752/Default.aspx. PRO-Sign adaptations of CEFR descriptors

are available in Czech, English, Estonian, German, Icelandic and Slovenian.

16. Bank of supplementary descriptors, available at www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/

bank-of-supplementary-descriptors.

17. Goodier T. (ed.) (2018), “Collated representative samples of descriptors of language competences developed for young learners – Resource

for educators, Volume 1: Ages 7-10”, Education Policy Division, Council of Europe, available at https://rm.coe.int/16808b1688.

18. Goodier T. (ed.) (2018), “Collated representative samples of descriptors of language competences developed for young learners – Resource

for educators, Volume 2: Ages 11-15”, Education Policy Division, Council of Europe, available at https://rm.coe.int/16808b1689.

Introduction Page 23

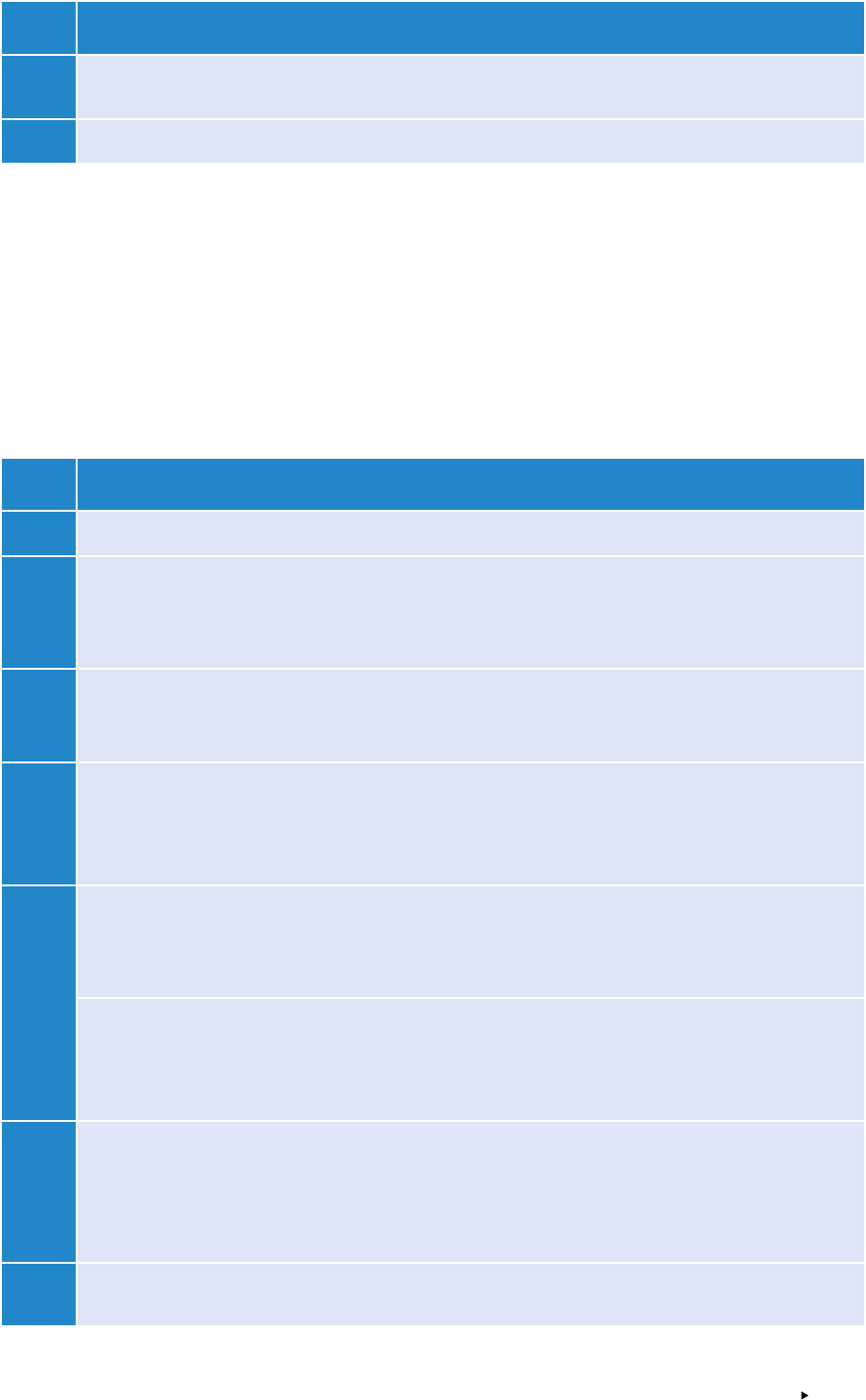

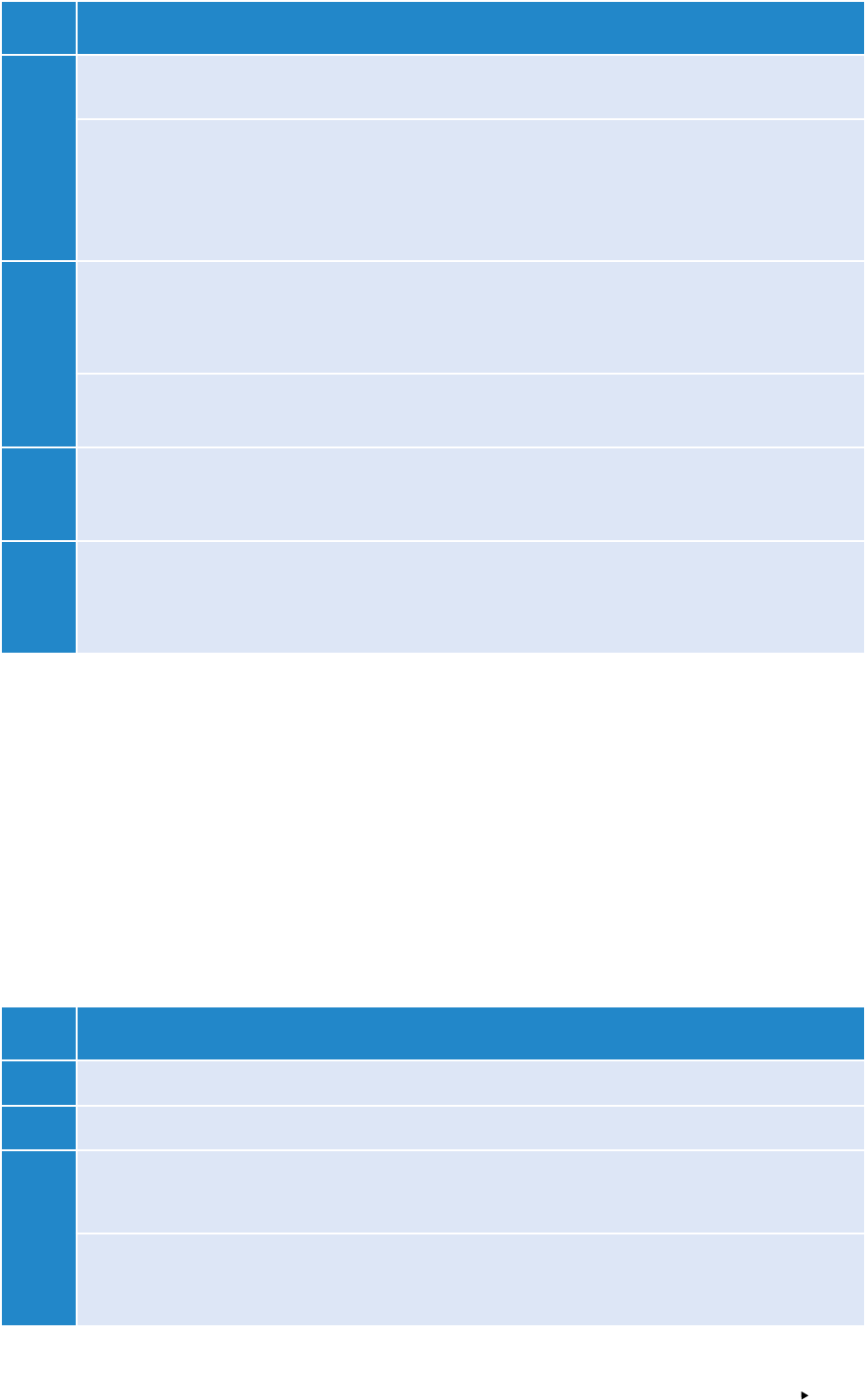

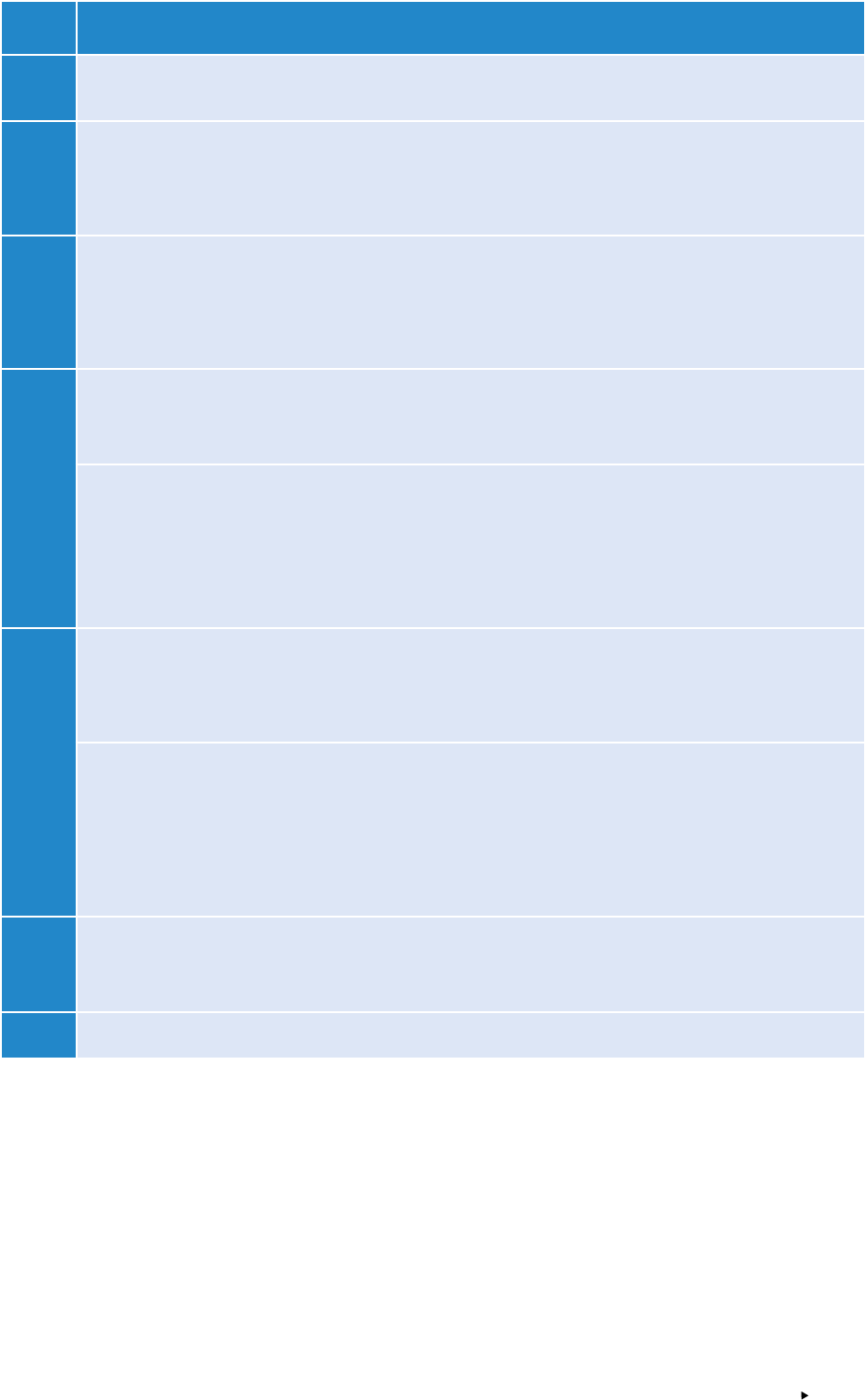

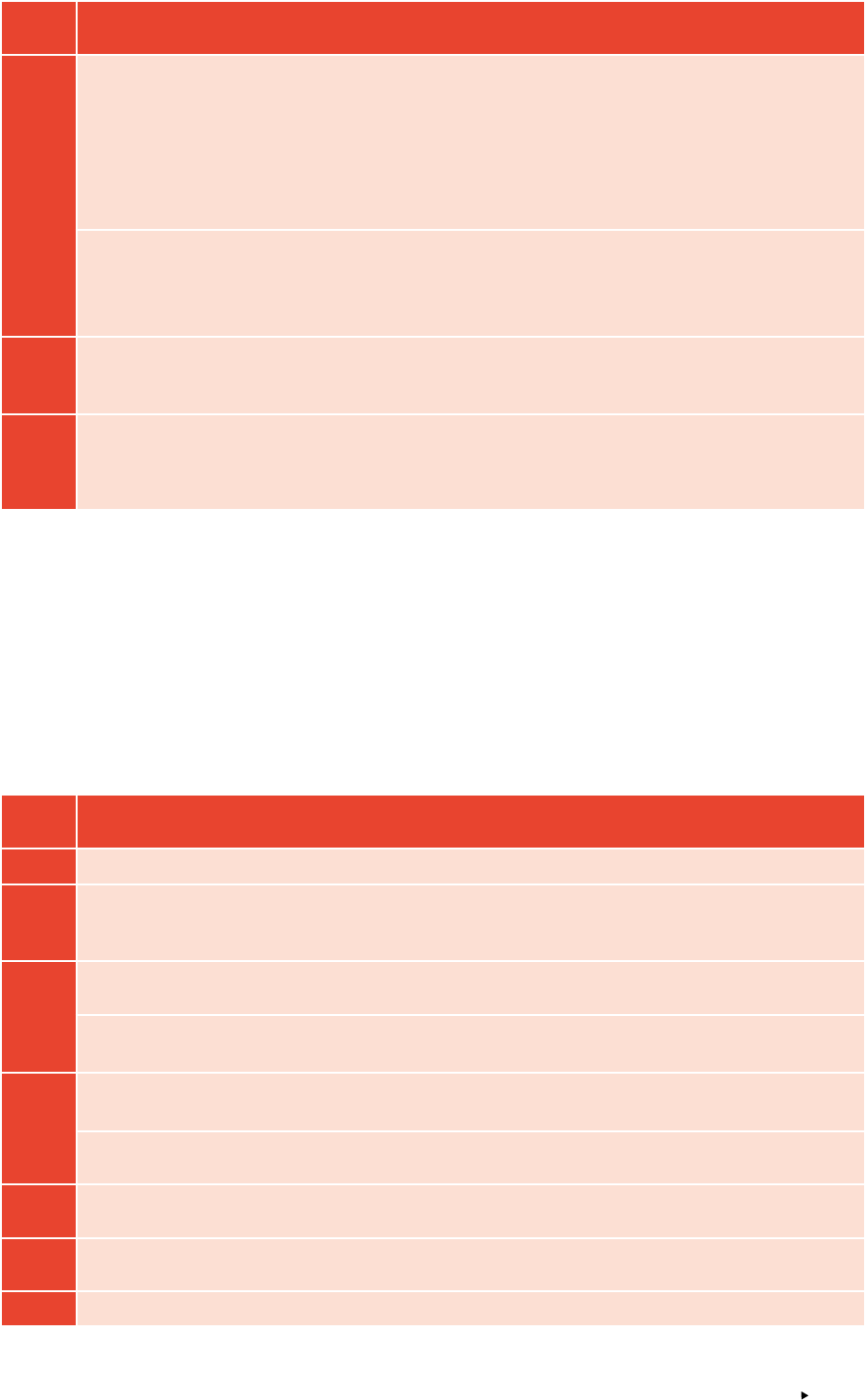

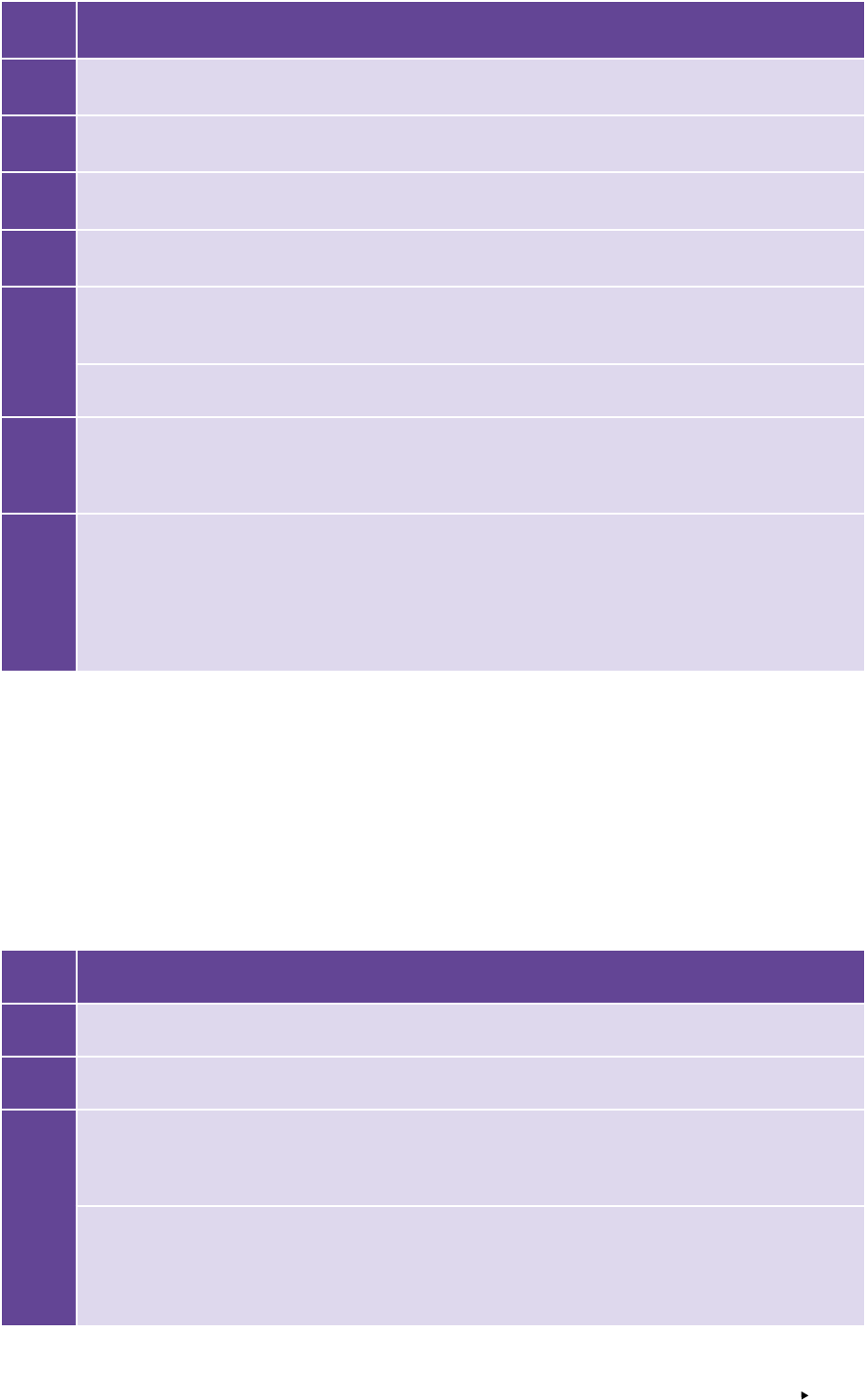

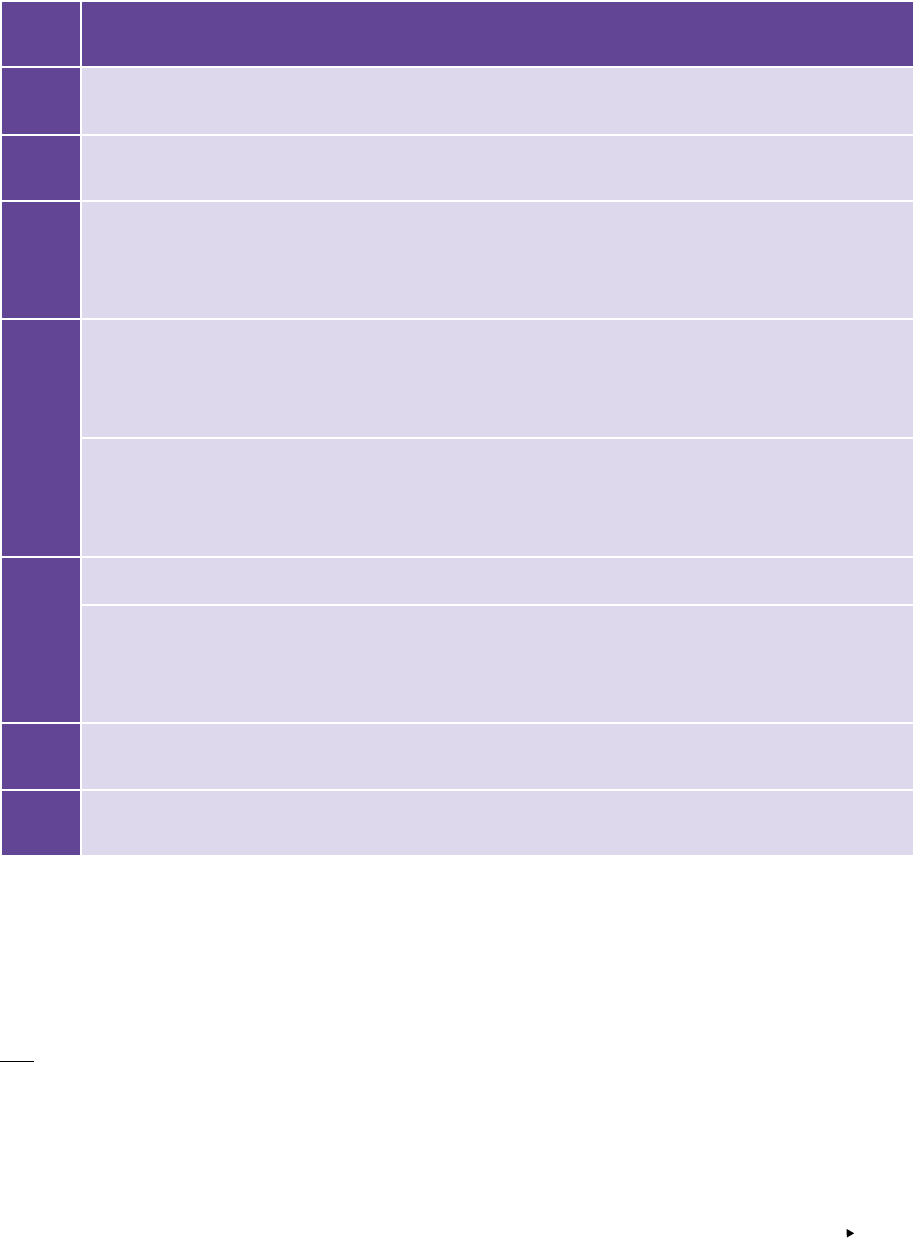

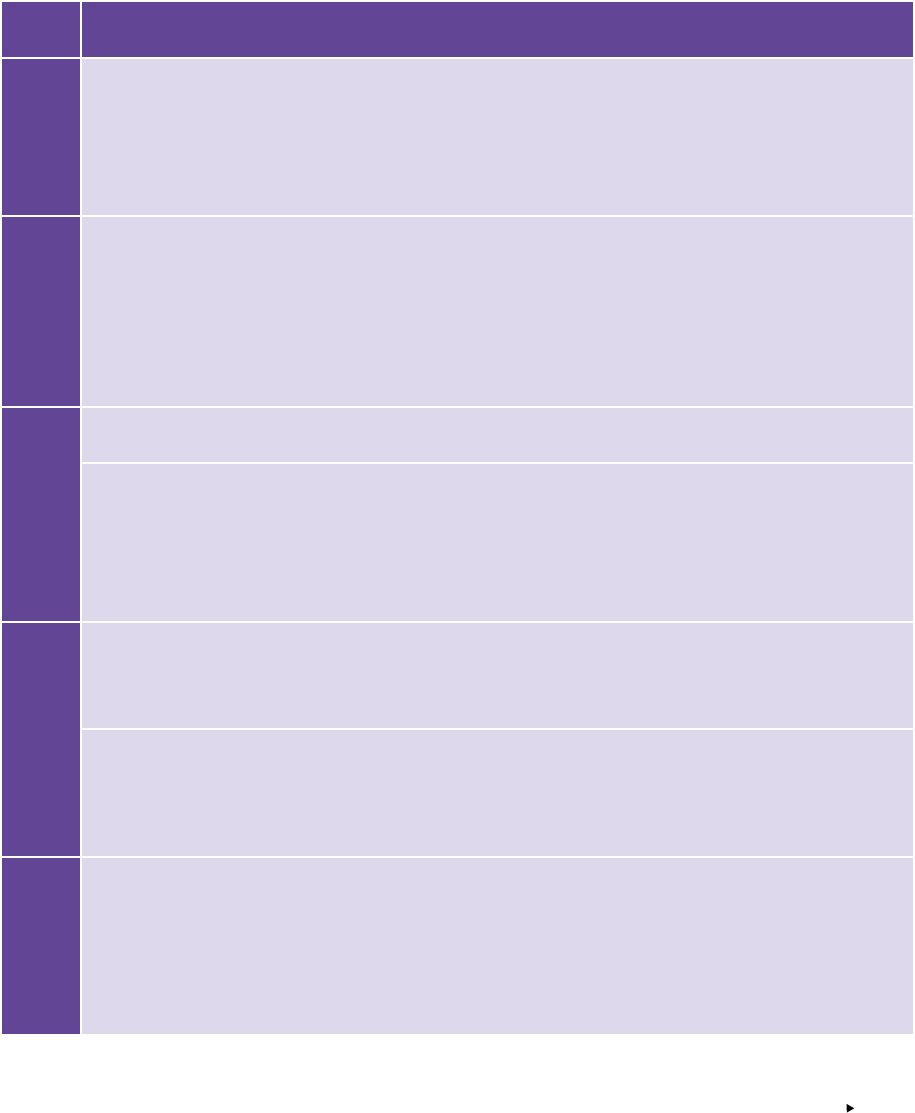

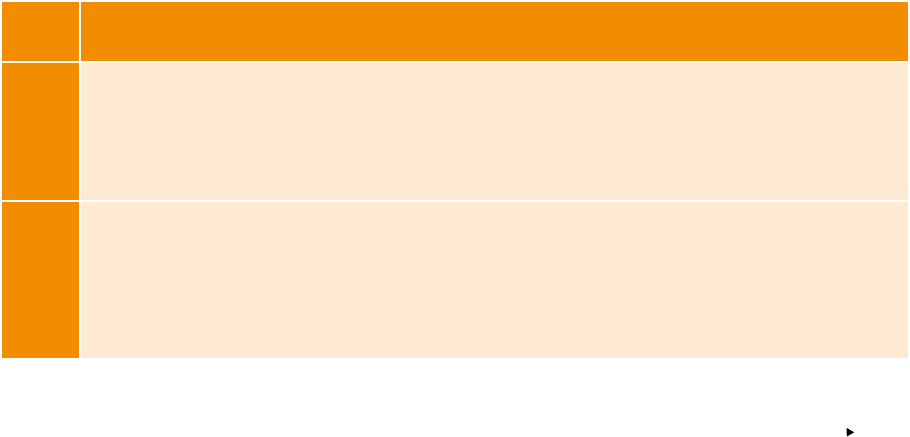

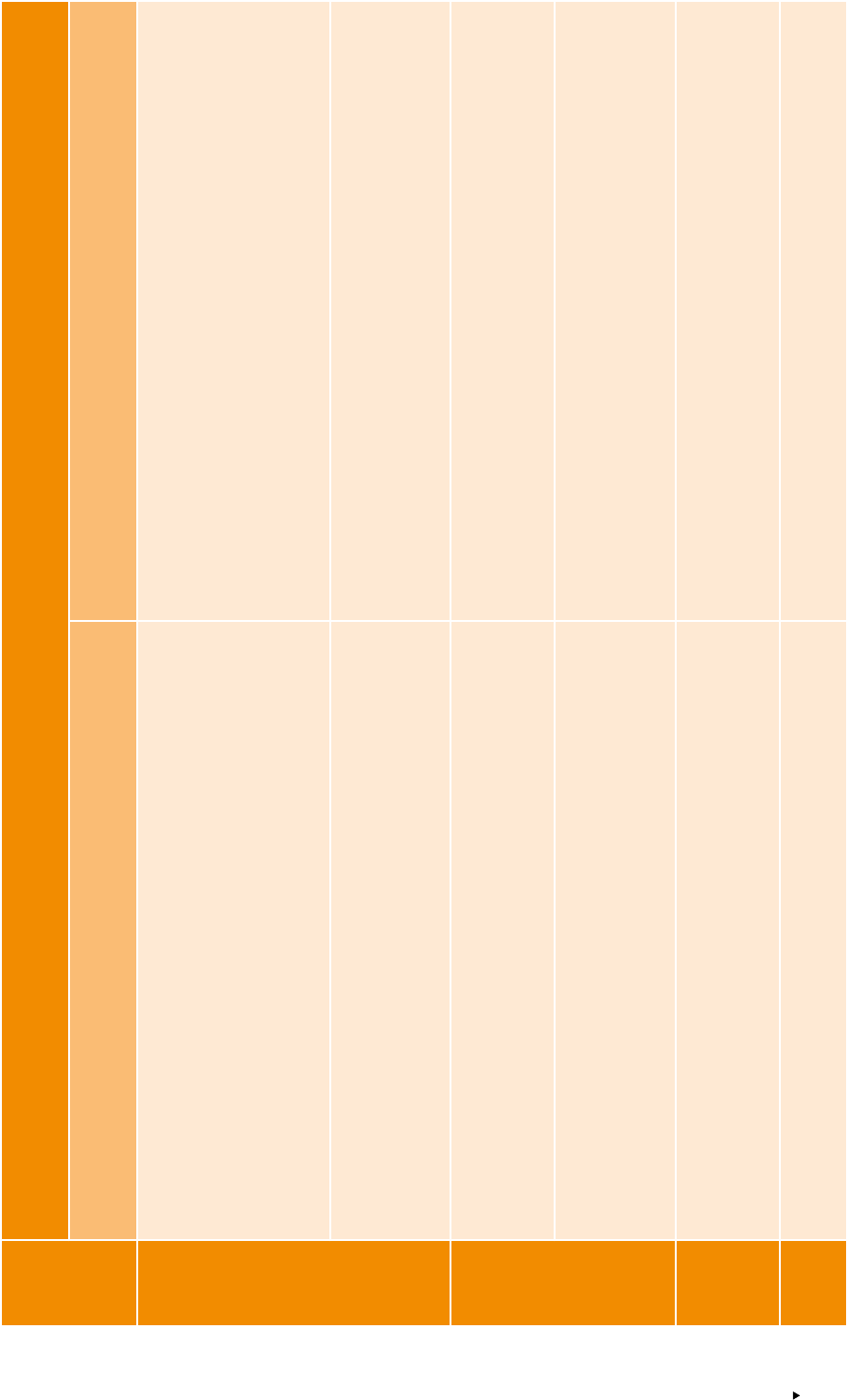

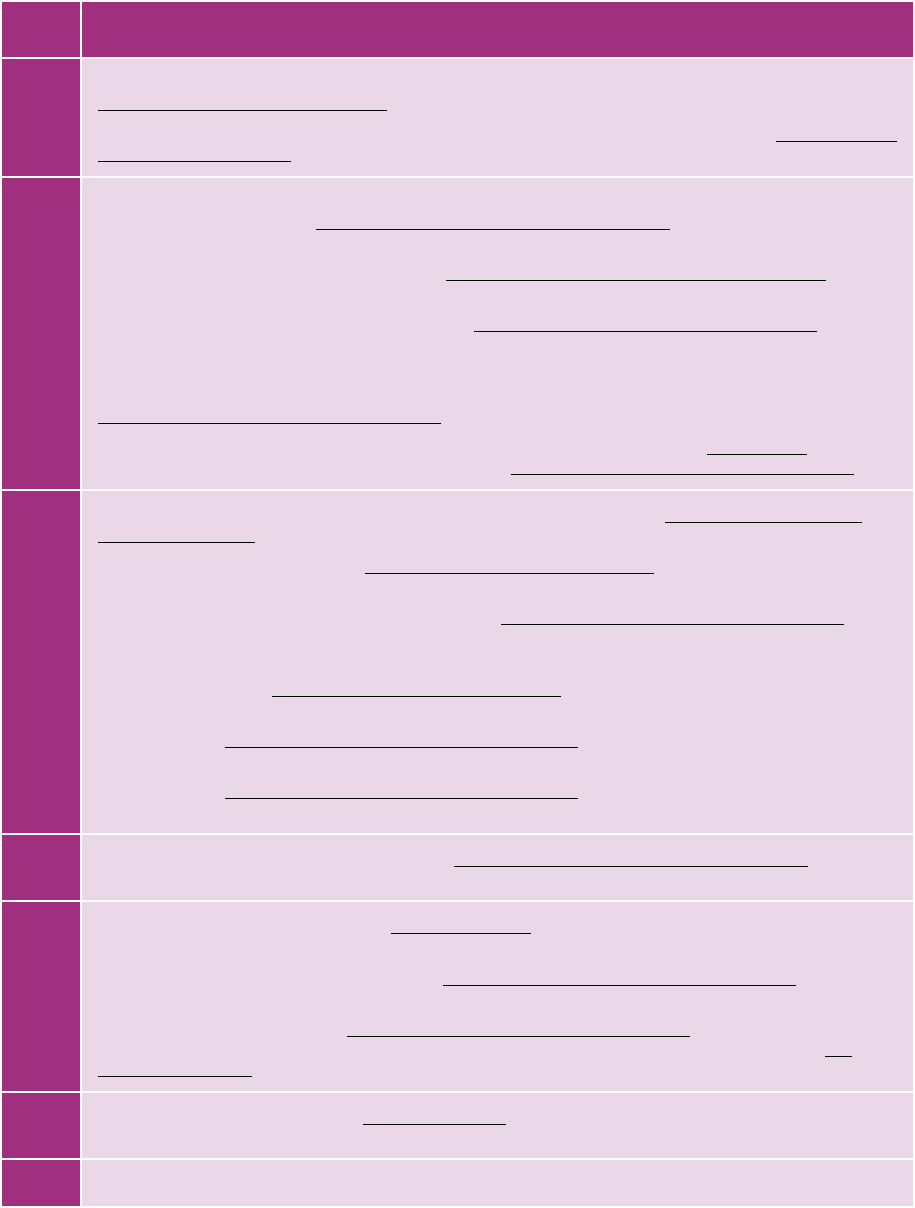

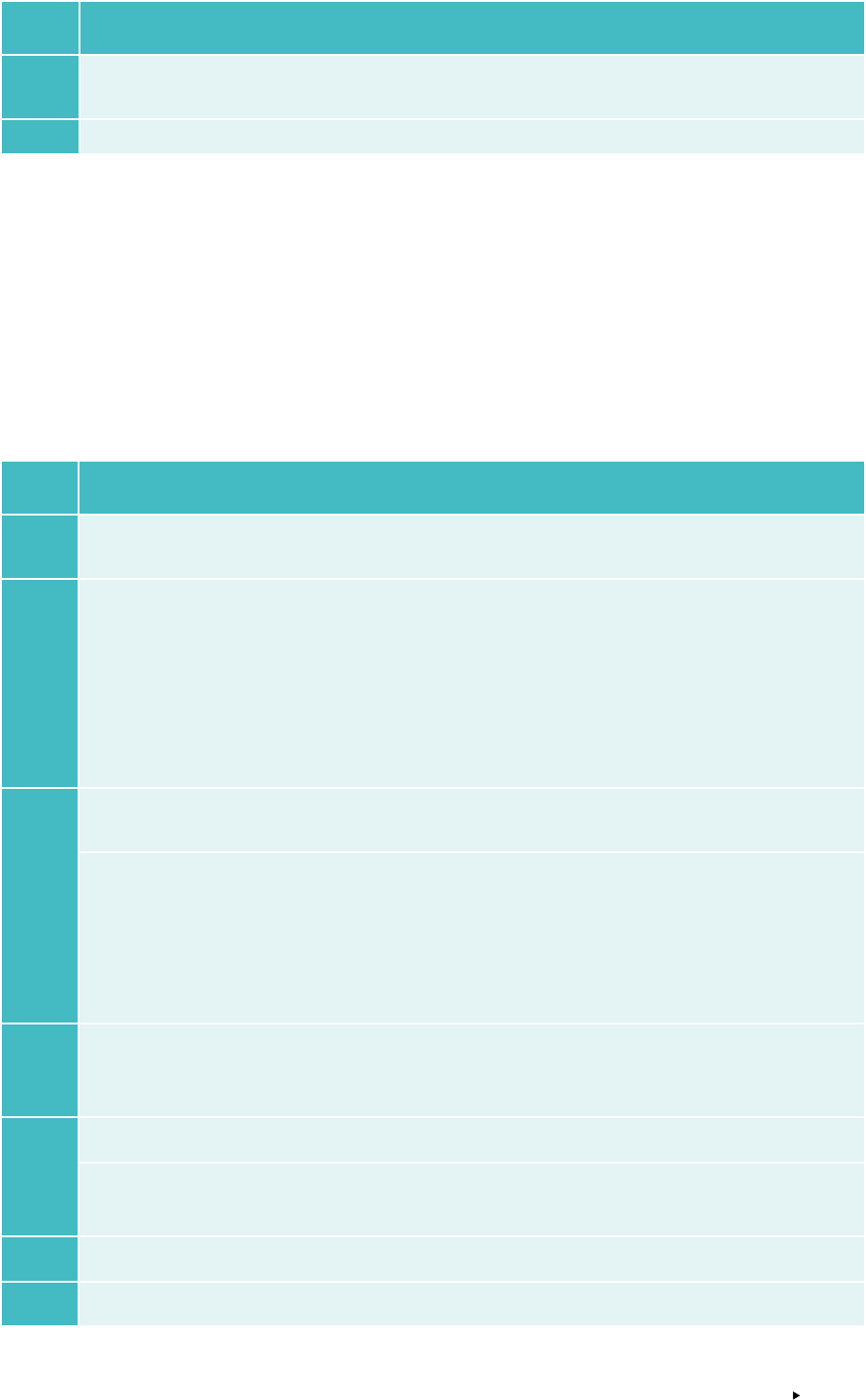

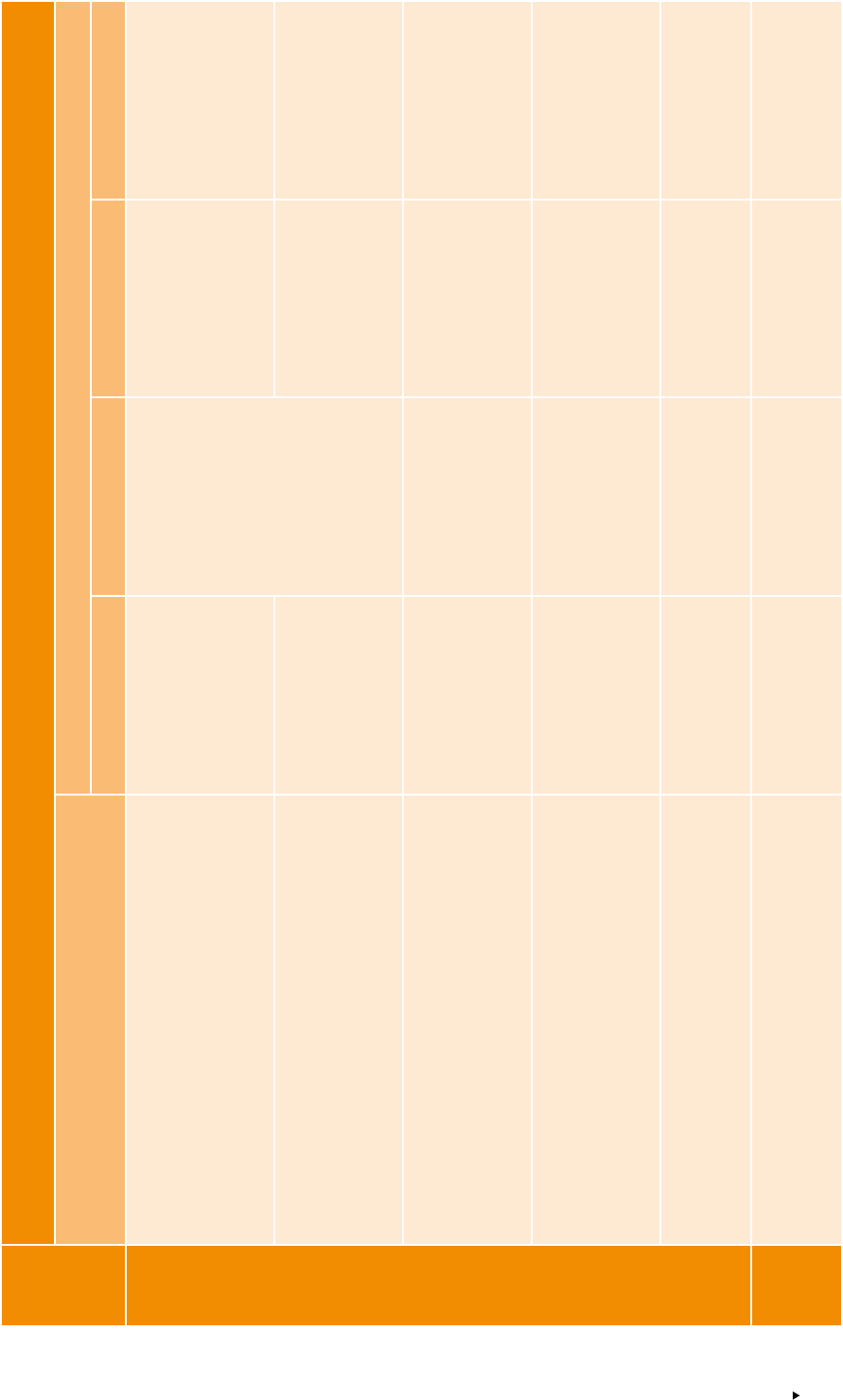

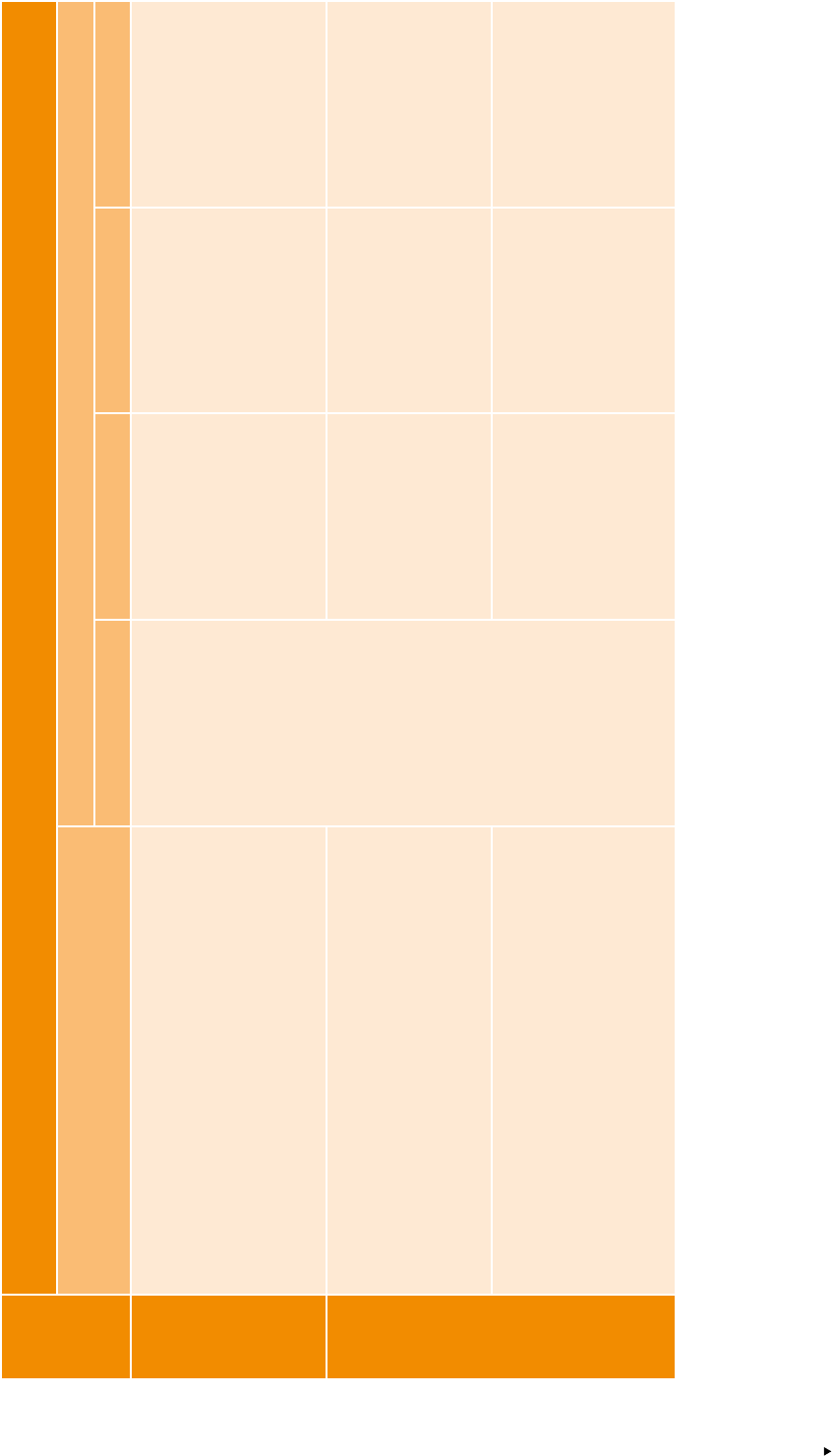

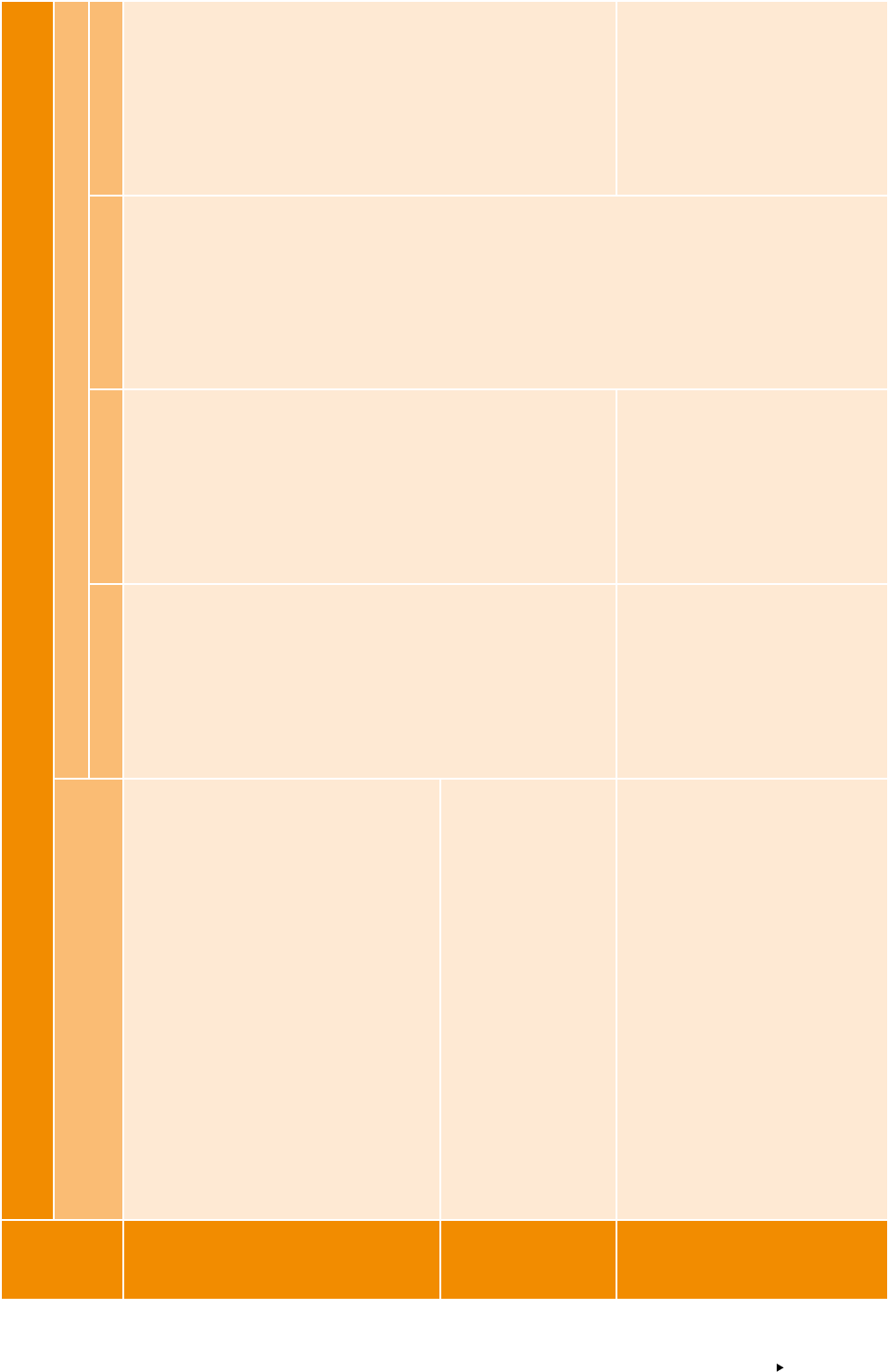

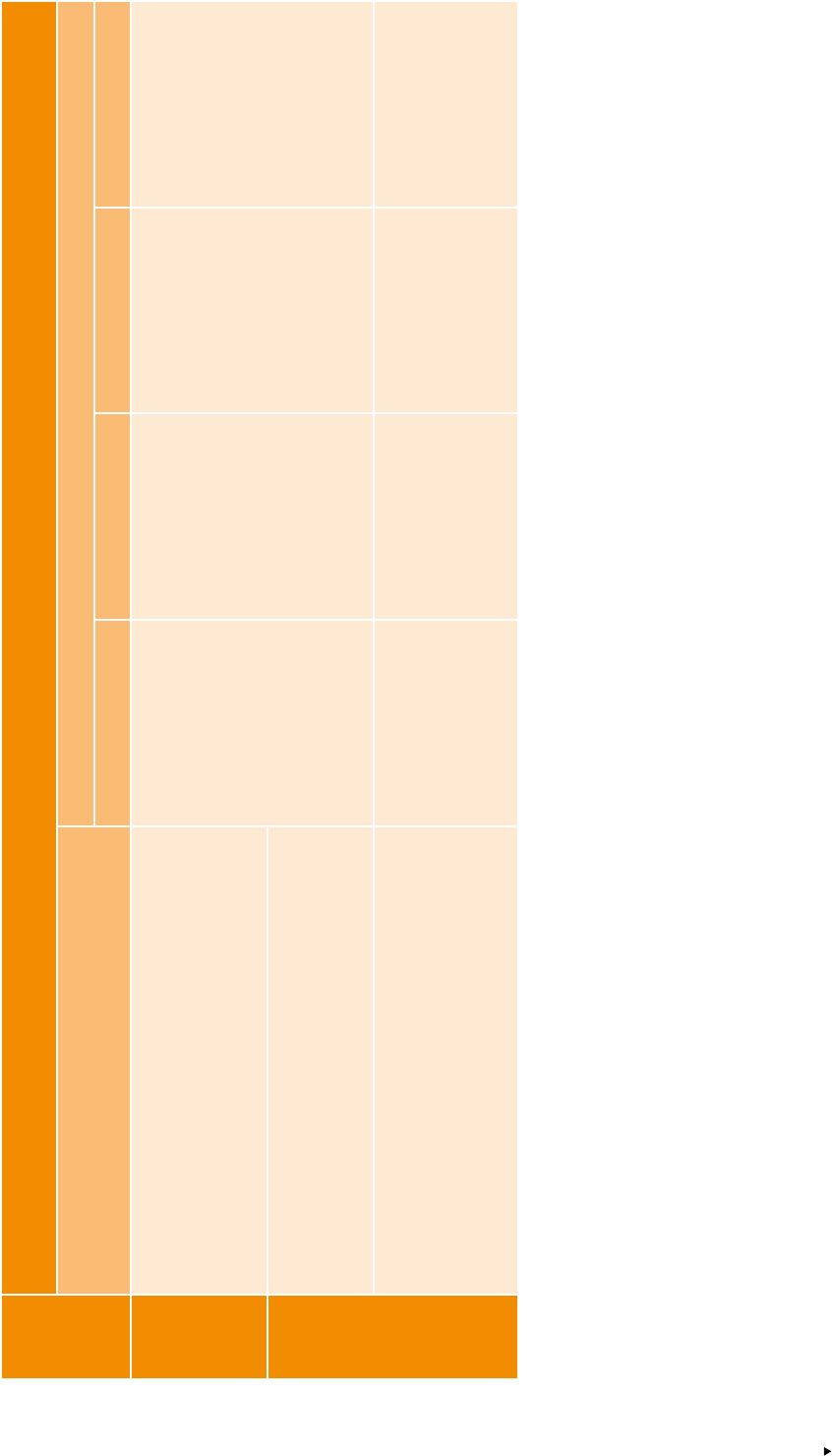

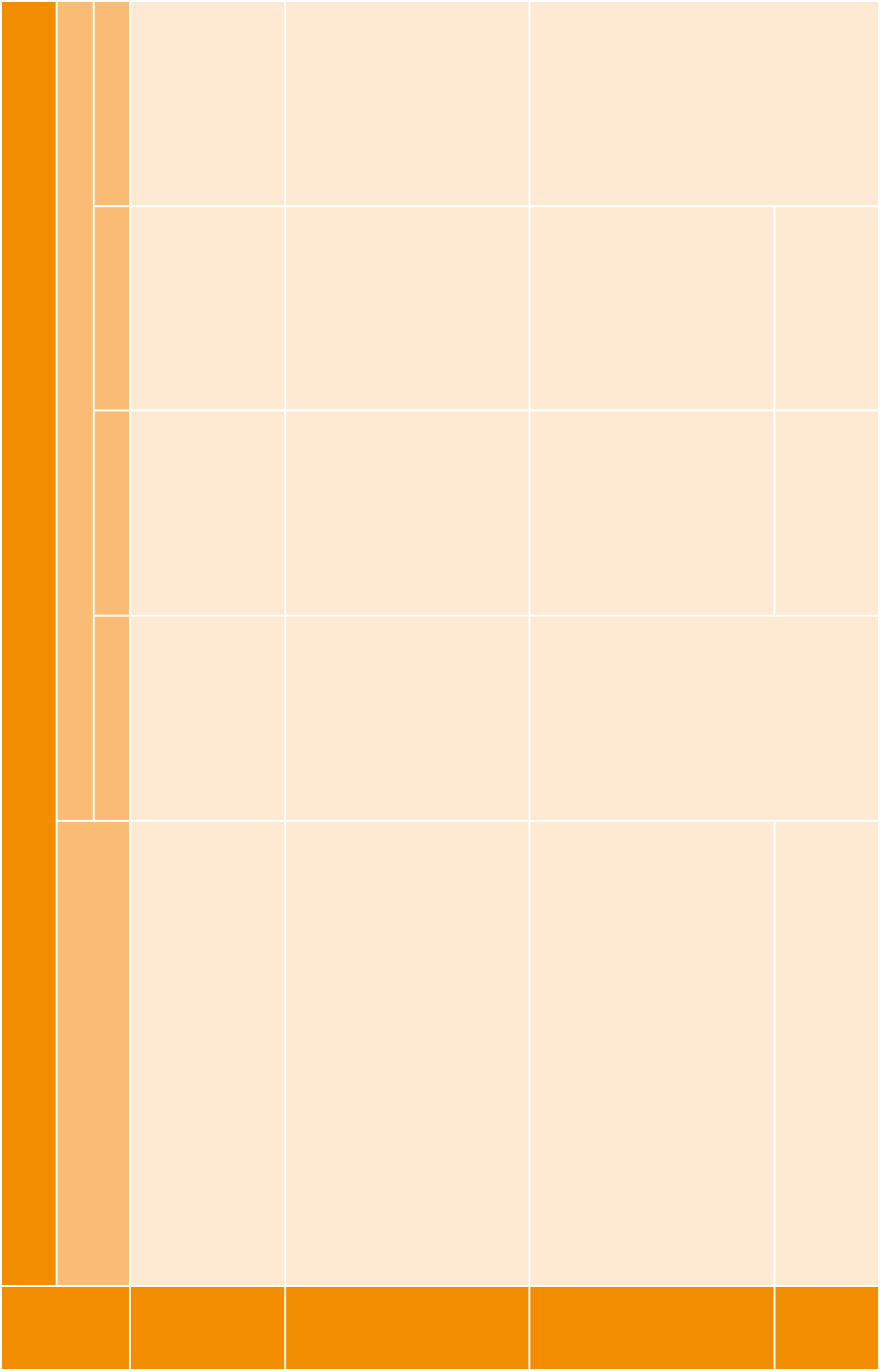

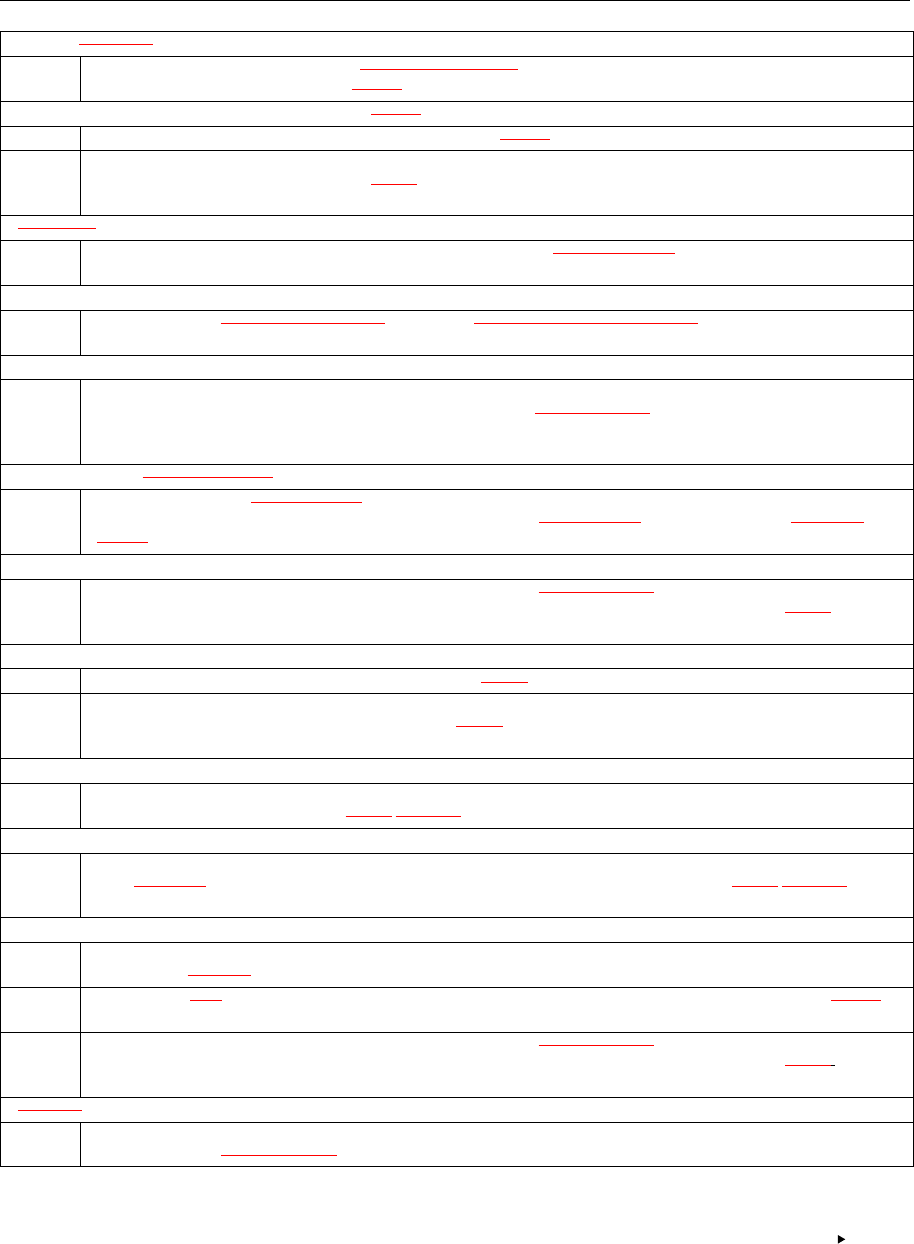

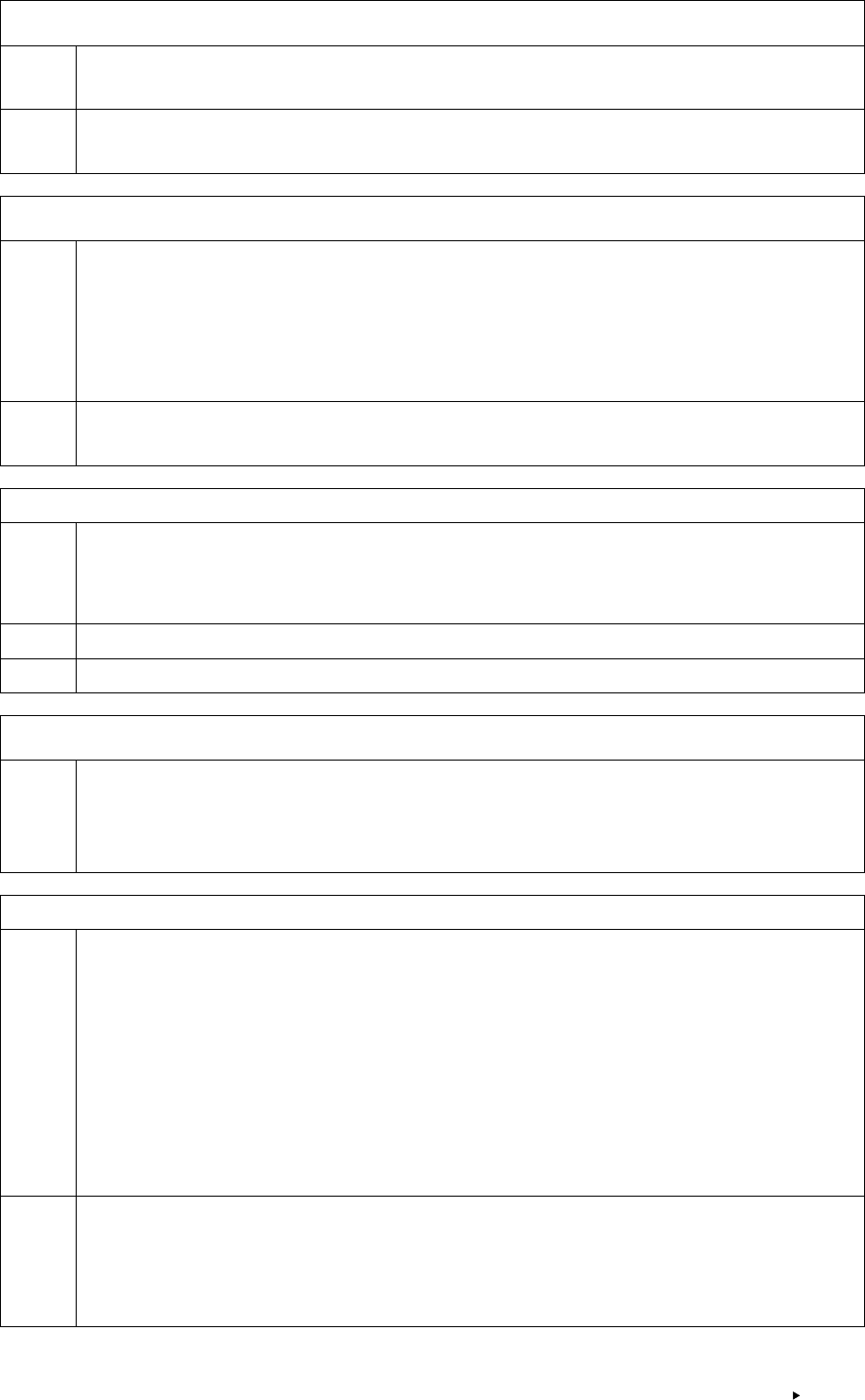

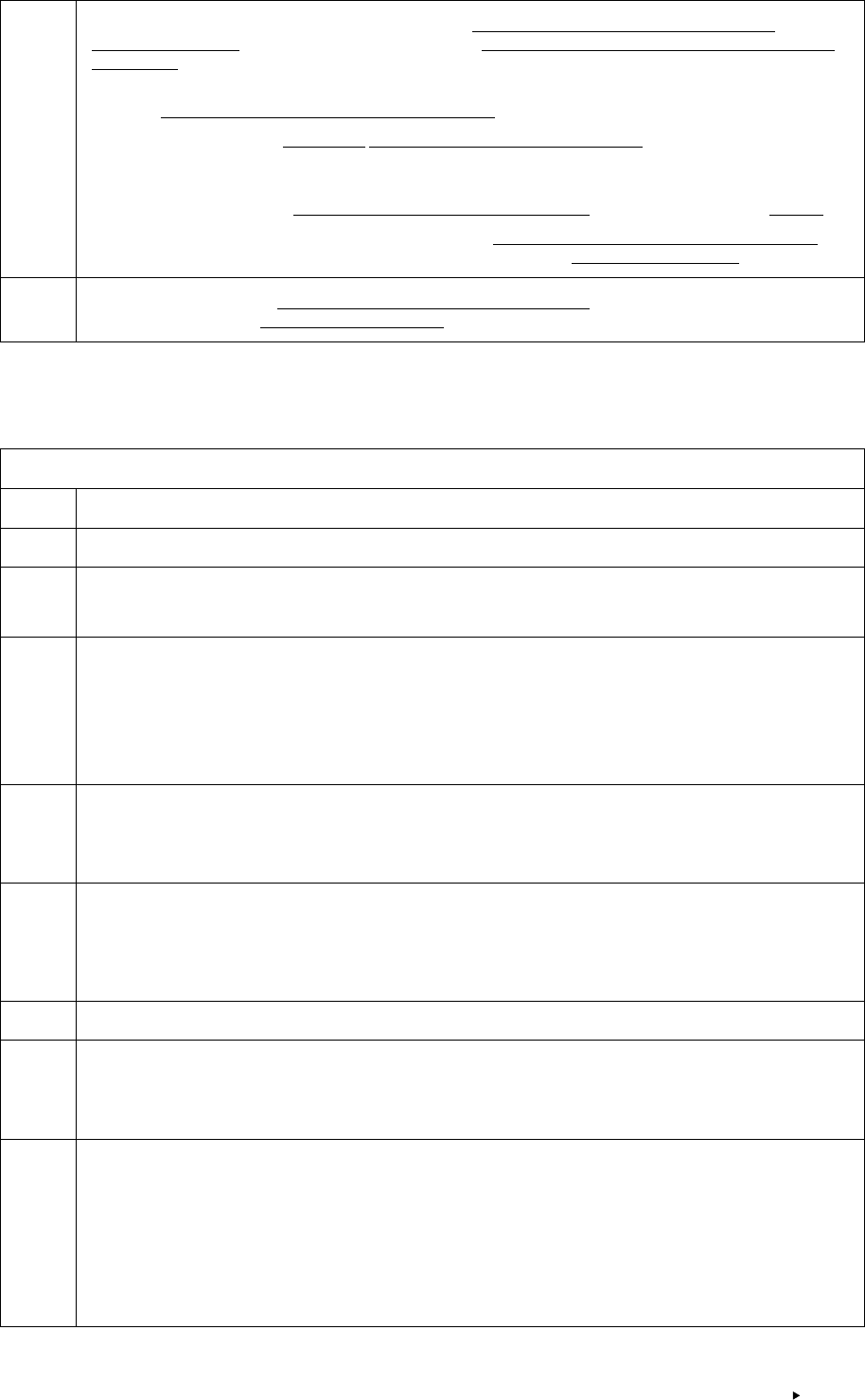

Table 1 – The CEFR descriptive scheme and illustrative descriptors: updates and additions

In the 2001

descriptive

scheme

In the

2001

descriptor

scales

Descriptor

scales

updated

in this

publication

Descriptor

scales

added

in this

publication

Communicative language activities

Reception

Oral comprehension √ √ √

Reading comprehension √ √ √

Production

Oral production √ √ √

Written production √ √ √

Interaction

Oral interaction √ √ √

Written interaction √ √ √

Online interaction √

Mediation

Mediating a text √ √

Mediating concepts √ √

Mediating communication √ √

Communicative language strategies

Reception √ √ √

Production √ √ √

Interaction √ √ √

Mediation √

Plurilingual and pluricultural

competence

Building on pluricultural repertoire √ √

Plurilingual comprehension √ √

Building on plurilingual repertoire √ √

Communicative language

competences

Linguistic competence √ √ √

√

(Phonology)

Sociolinguistic competence √ √ √

Pragmatic competence √ √ √

Signing competences

Linguistic competence √

Sociolinguistic competence √

Pragmatic competence √

Page 24 3 CEFR – Companion volume

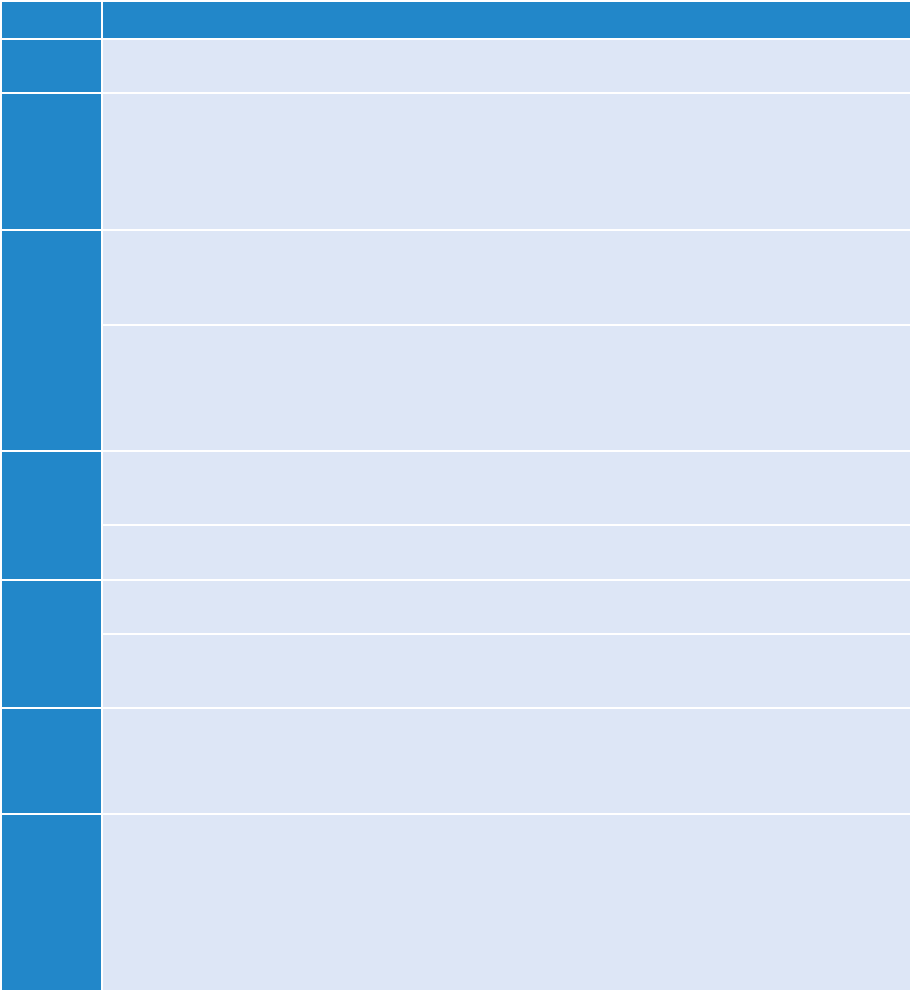

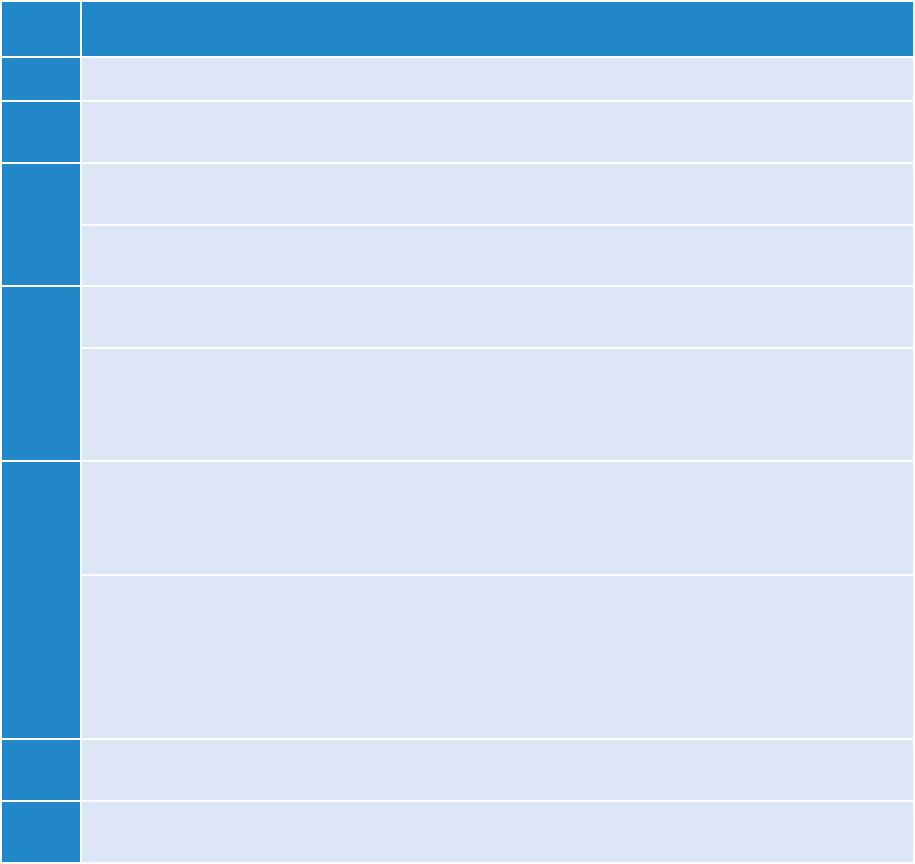

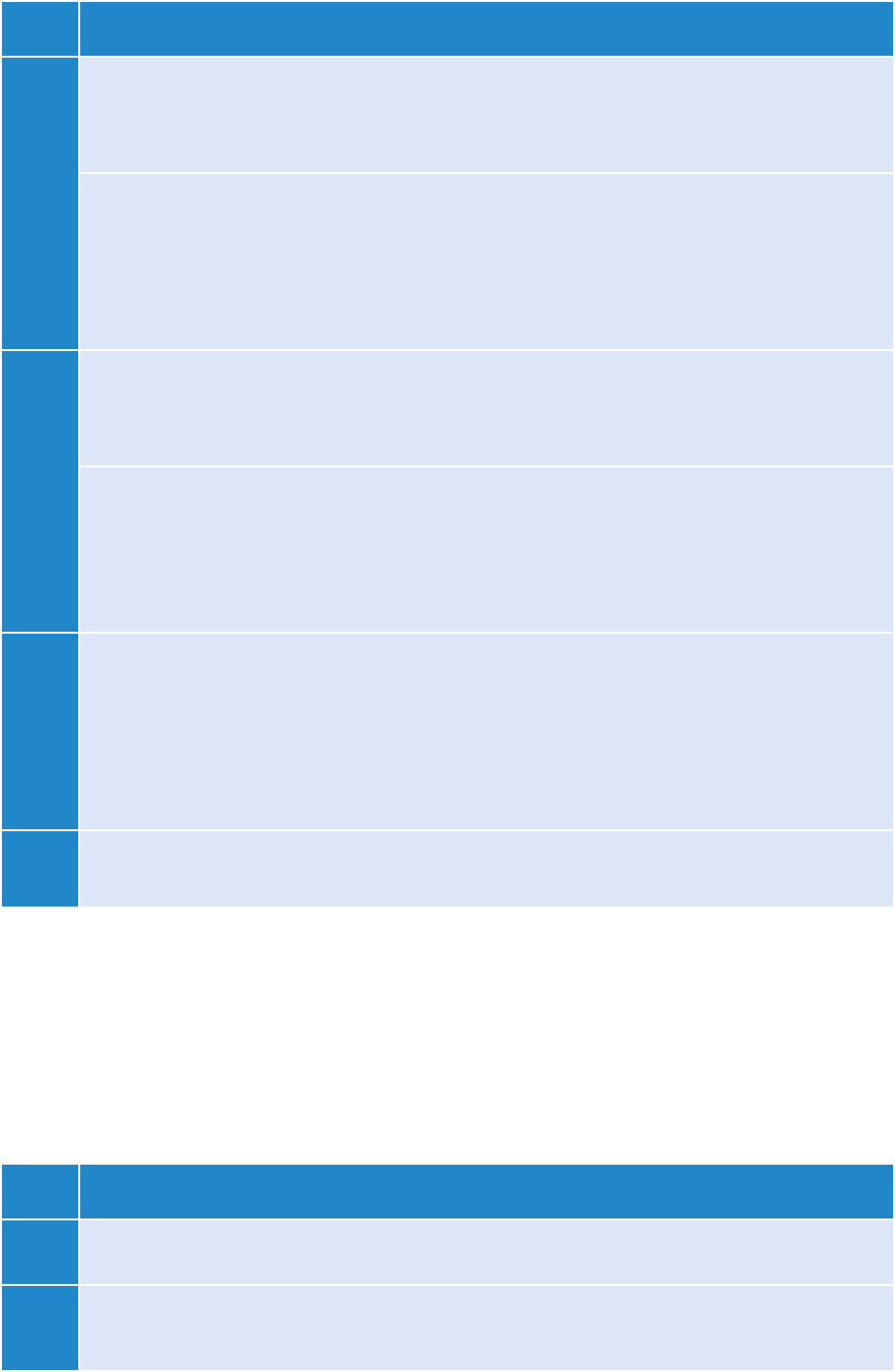

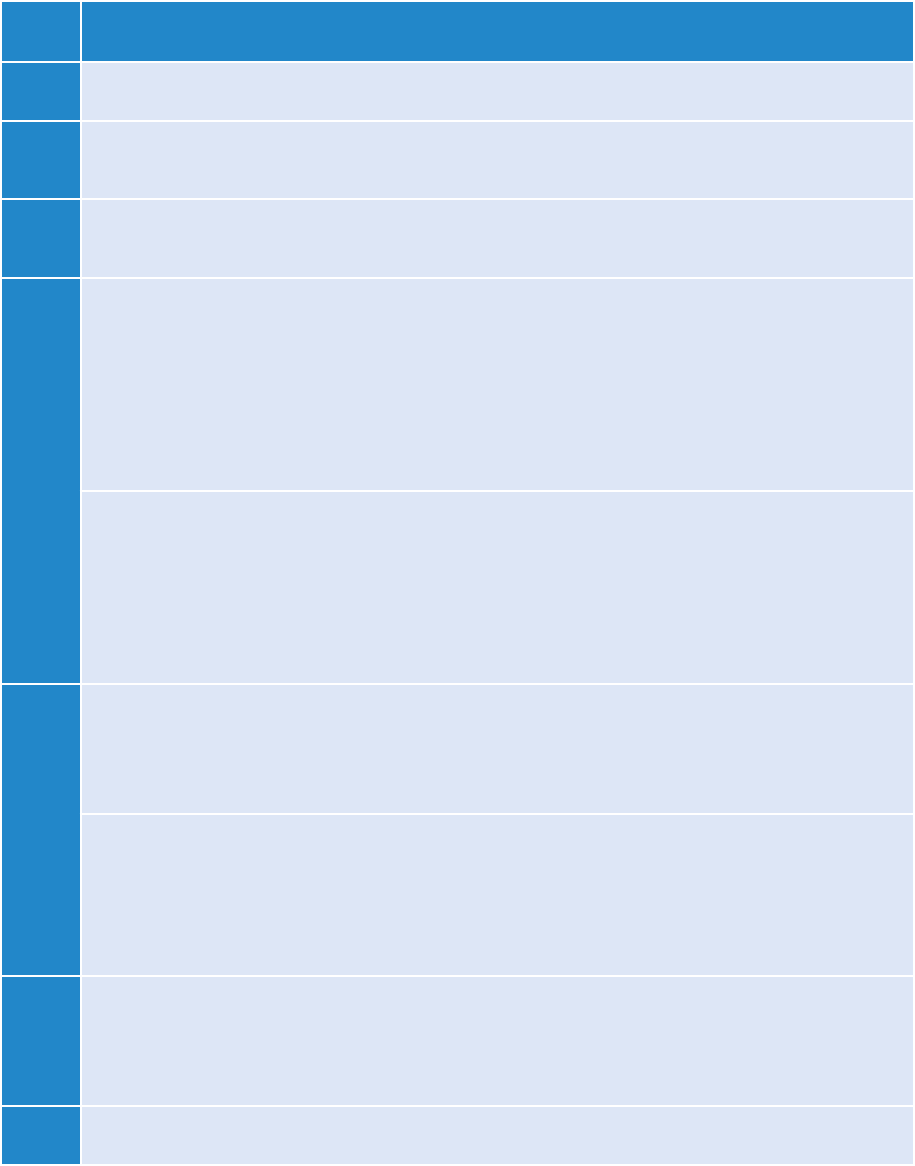

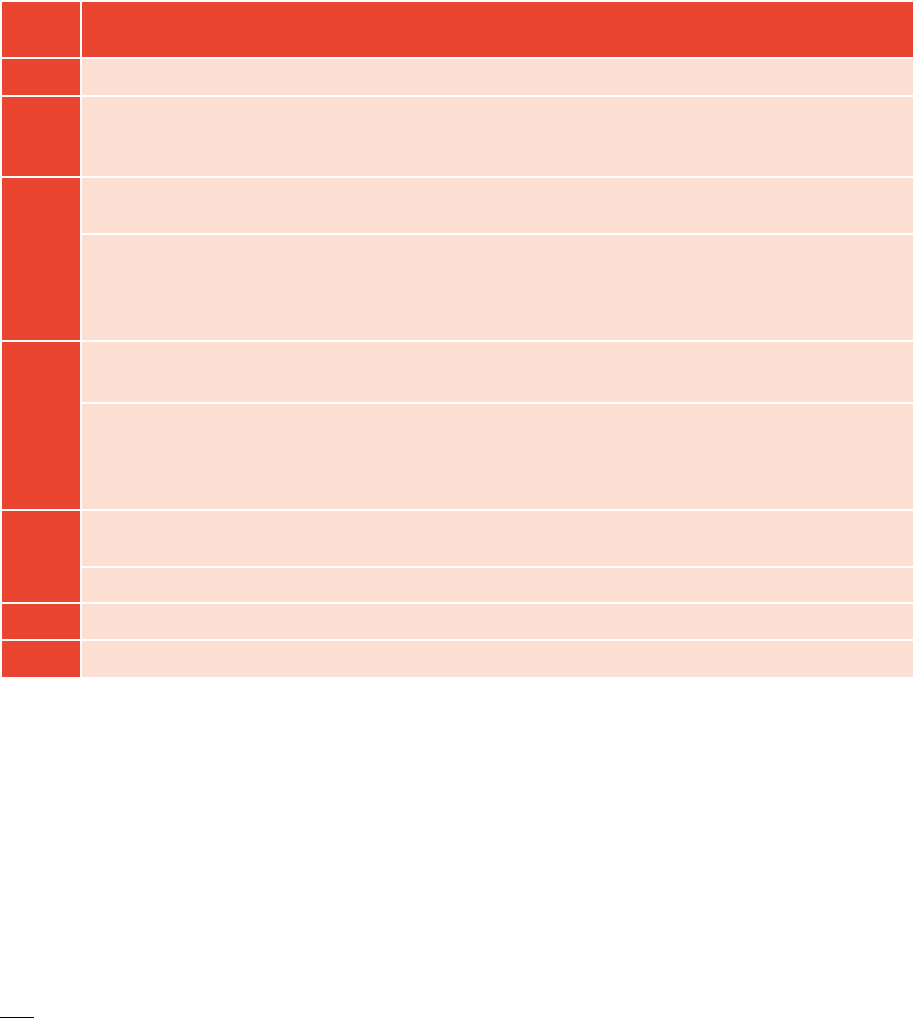

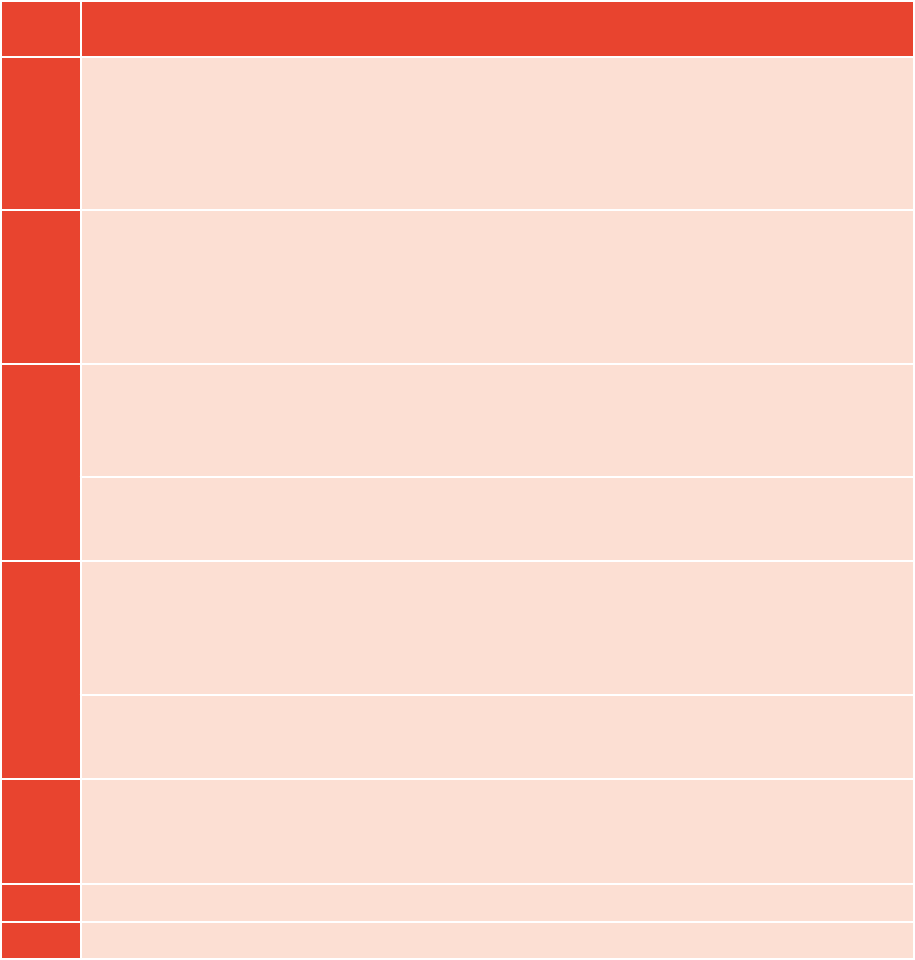

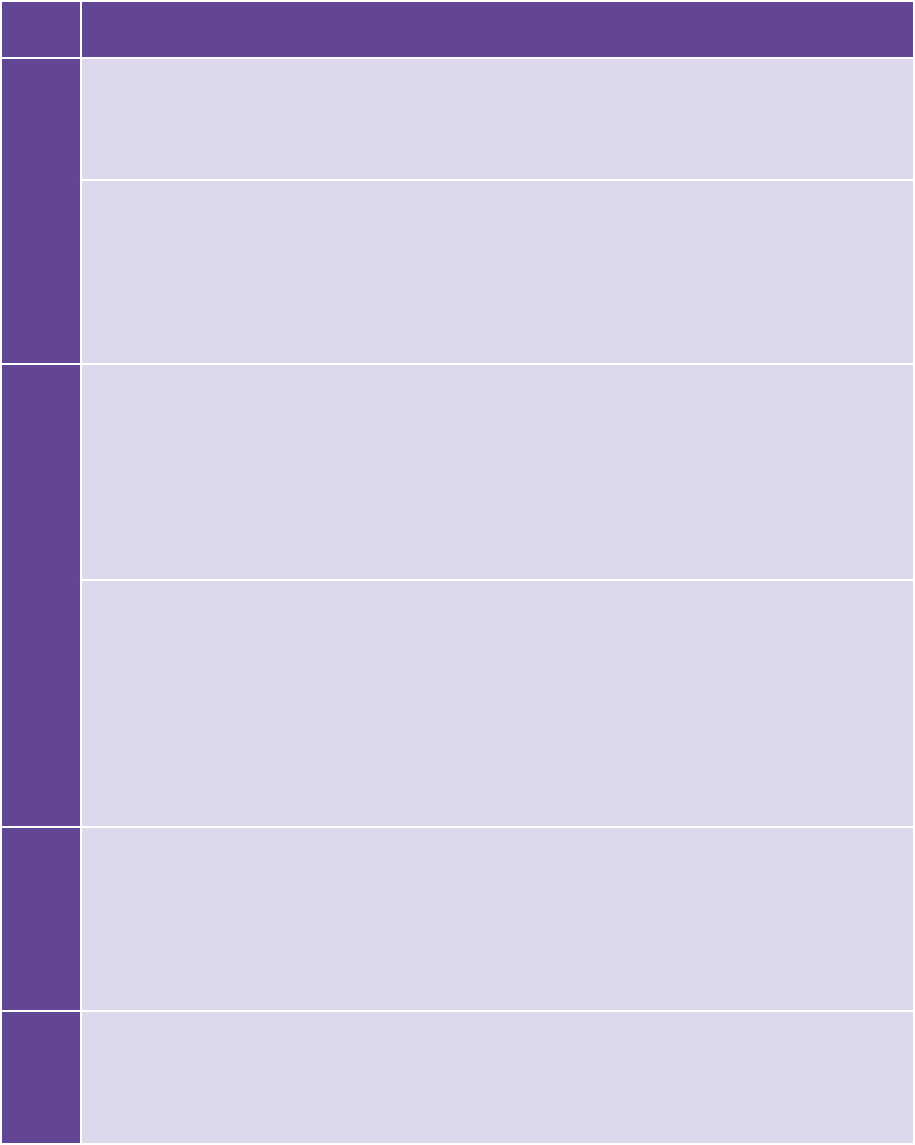

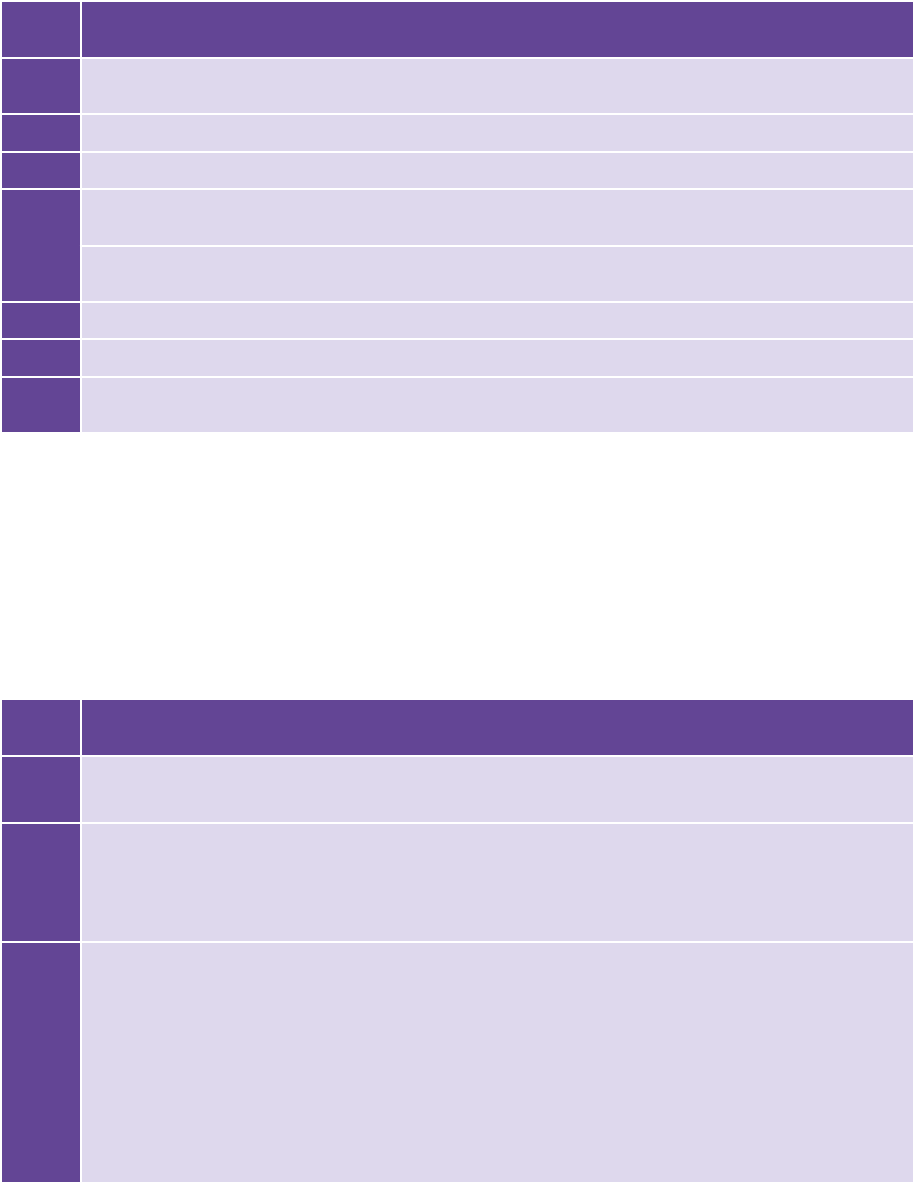

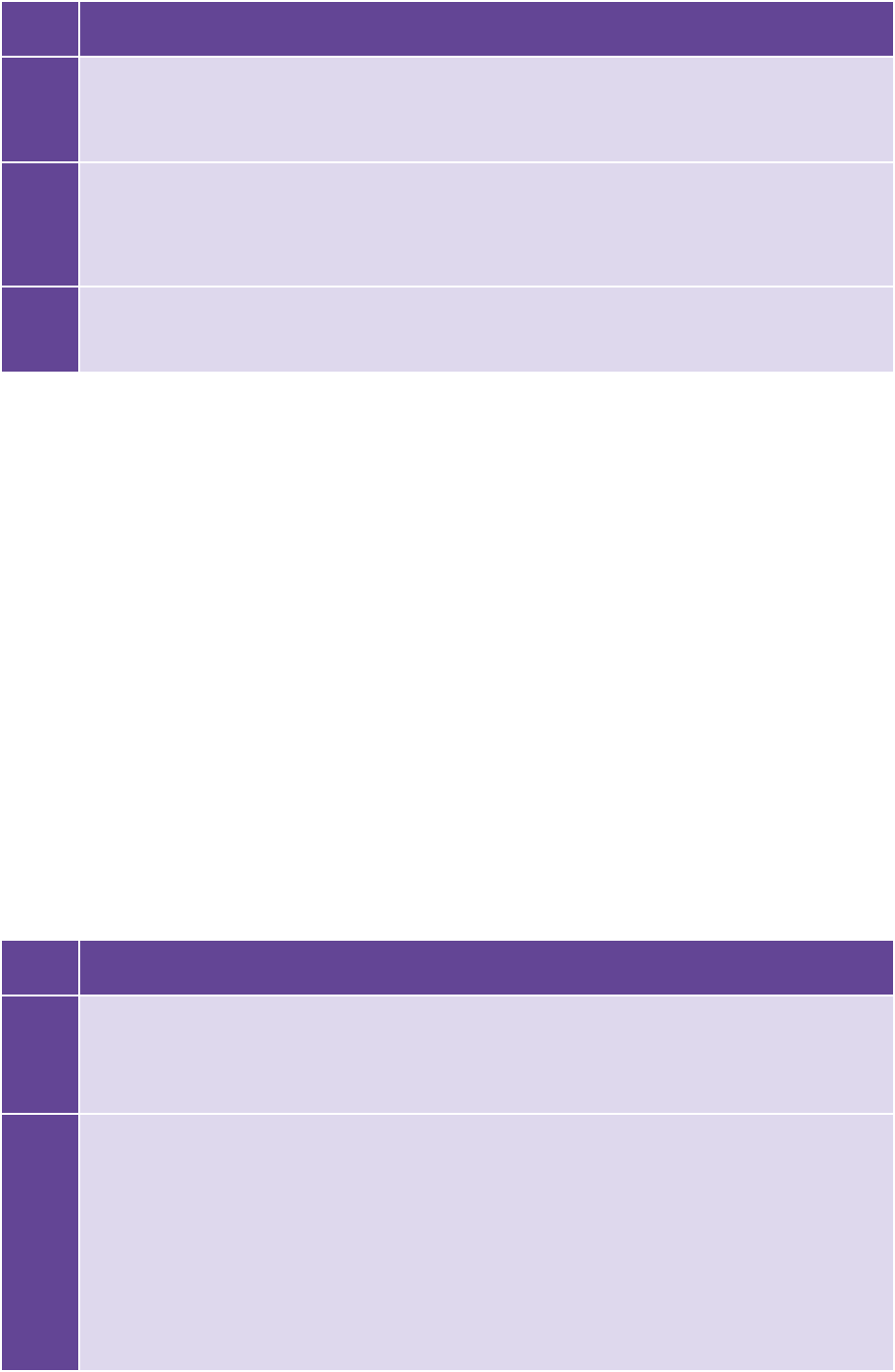

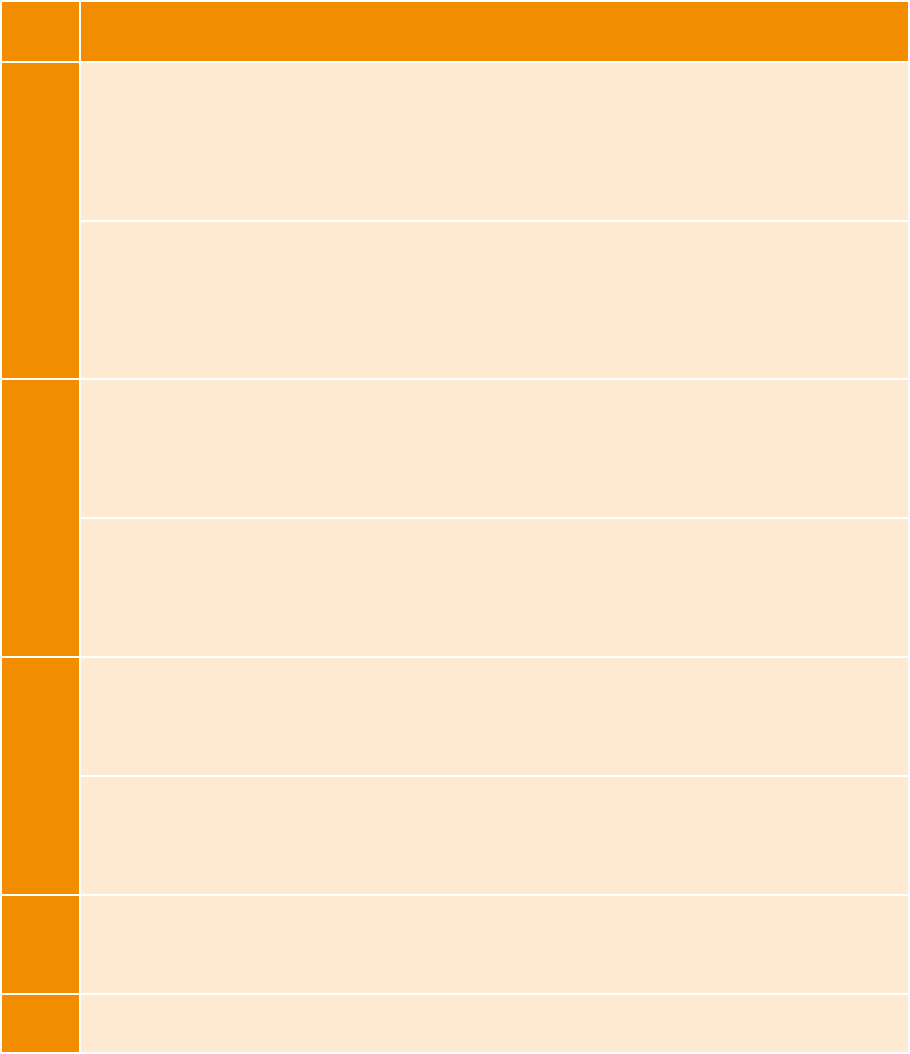

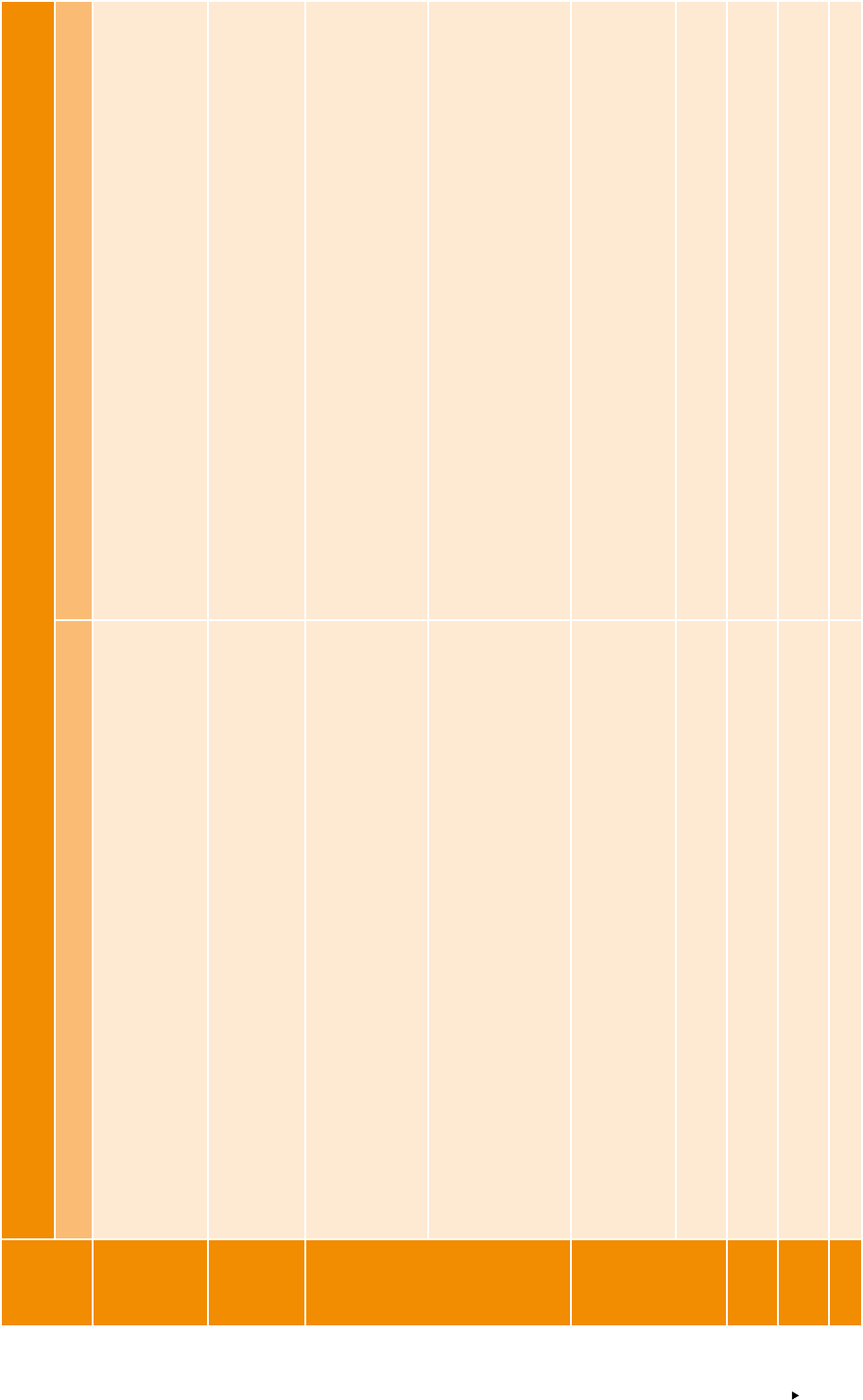

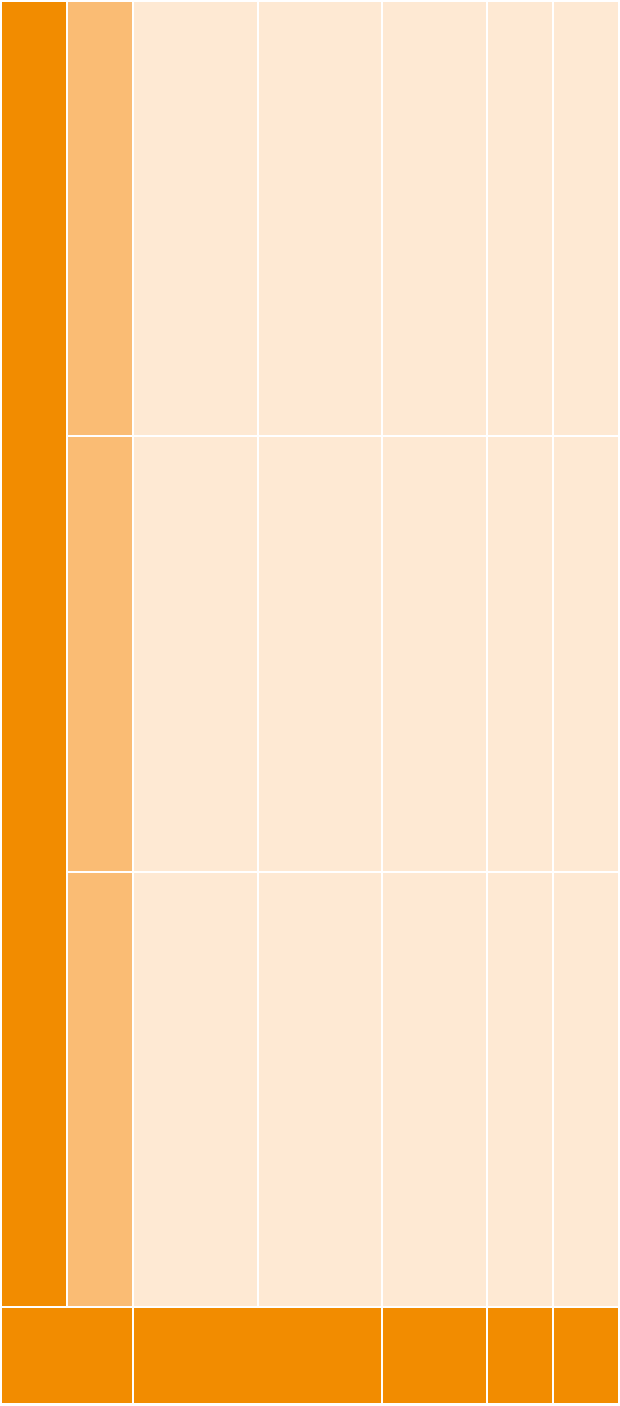

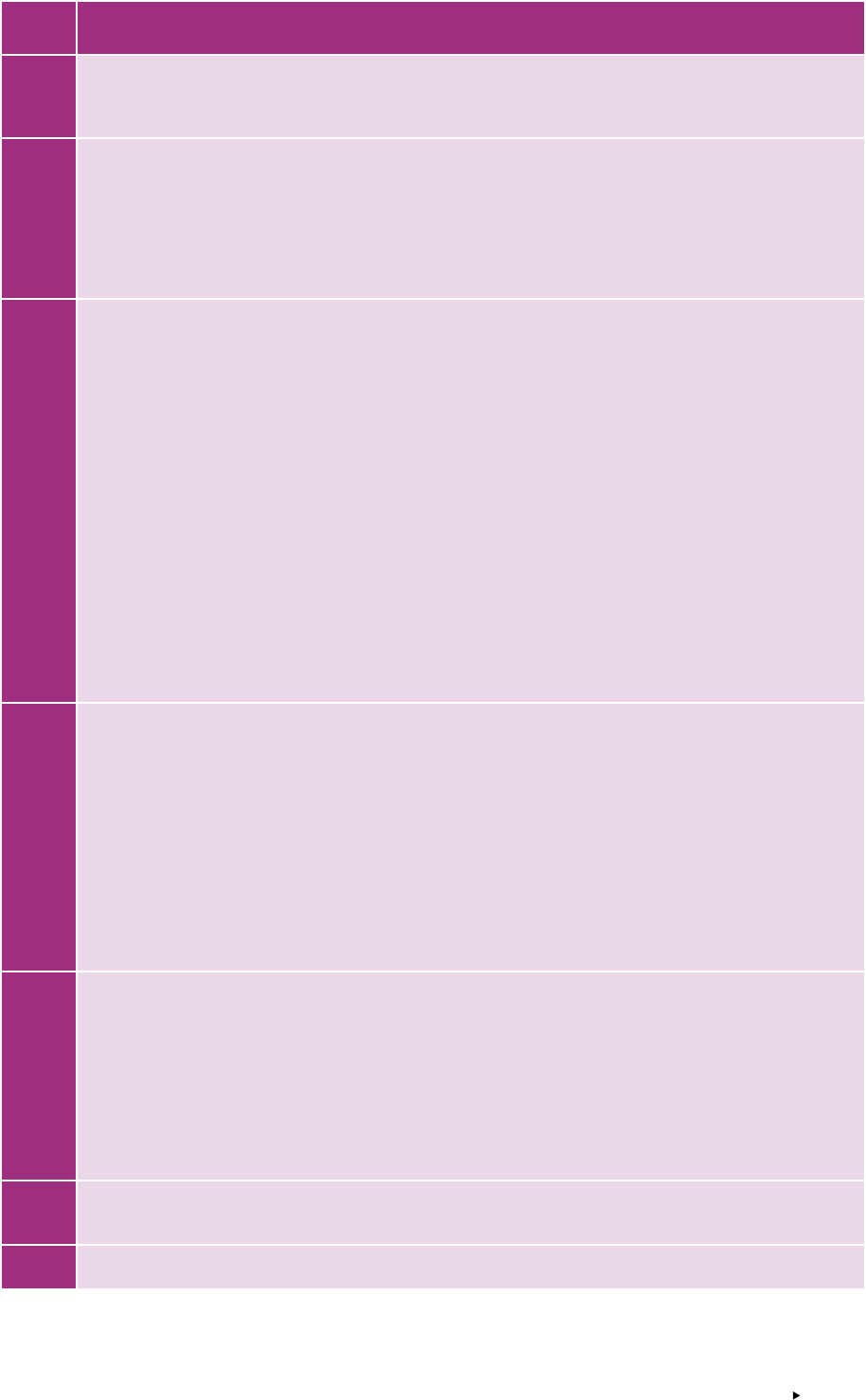

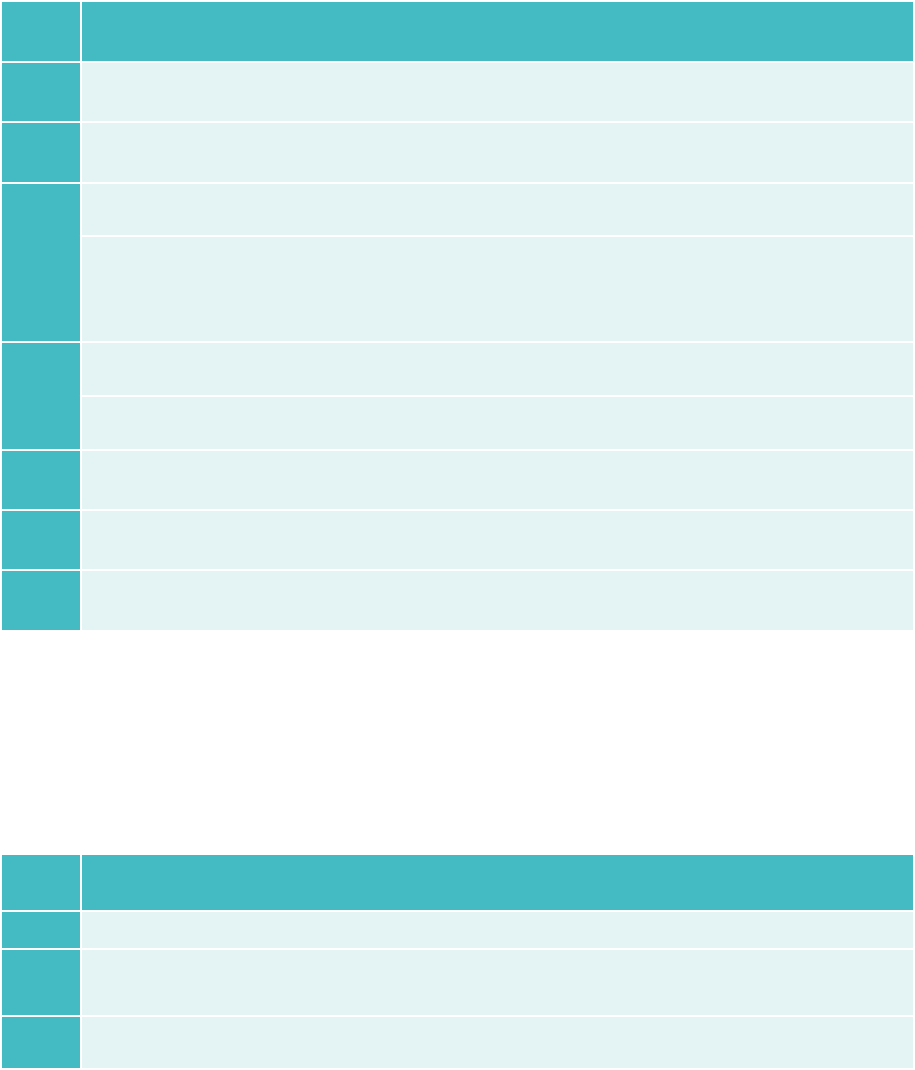

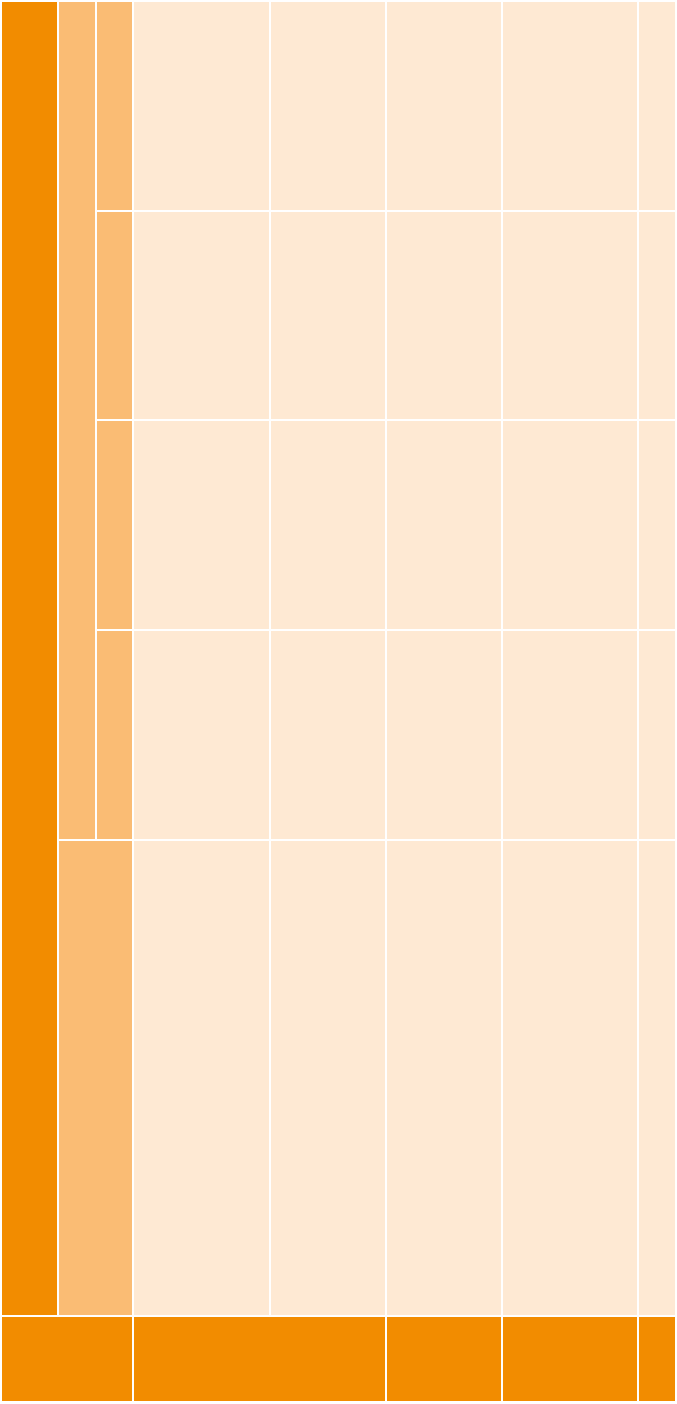

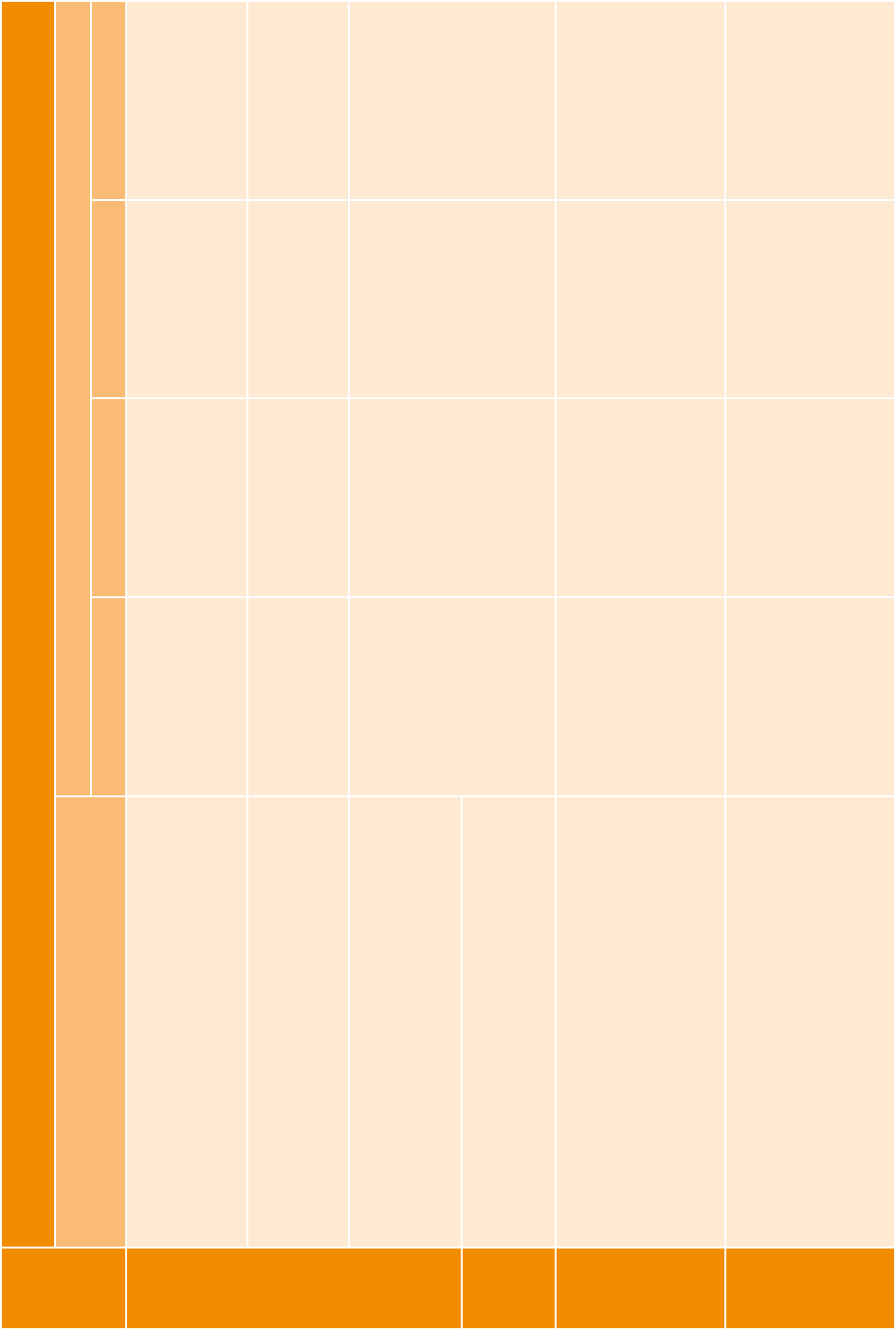

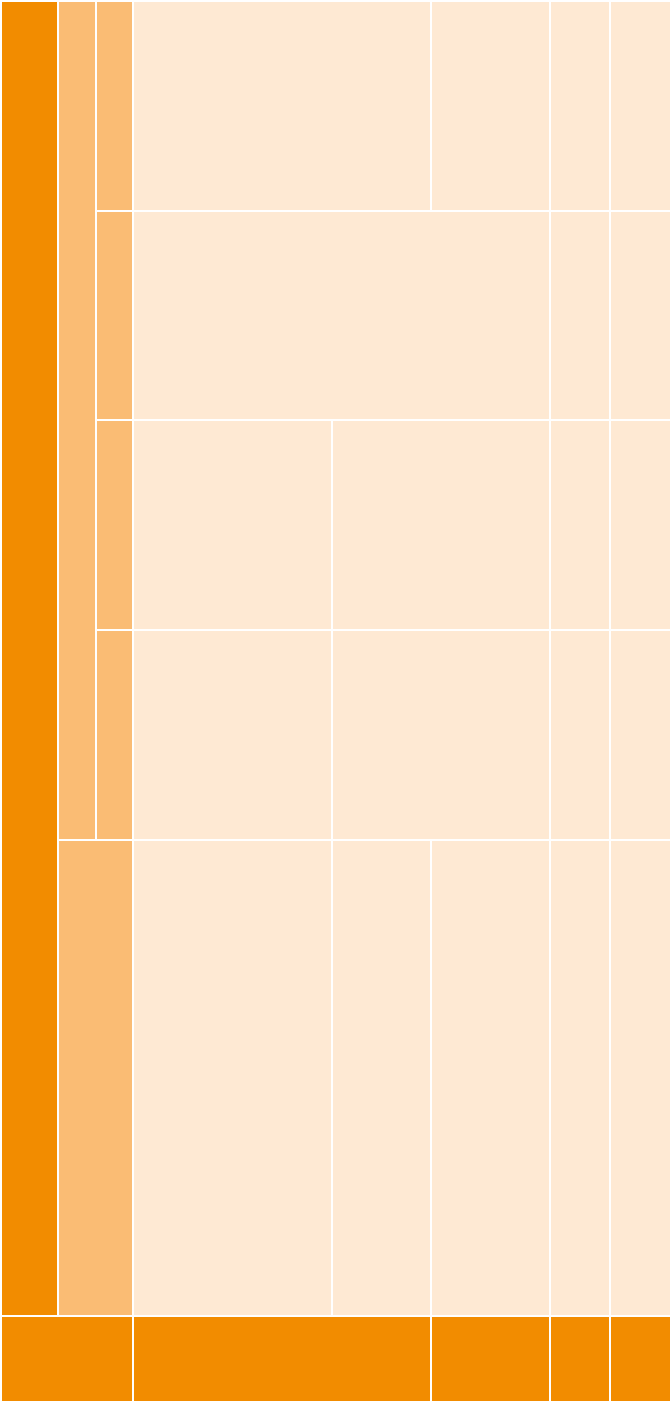

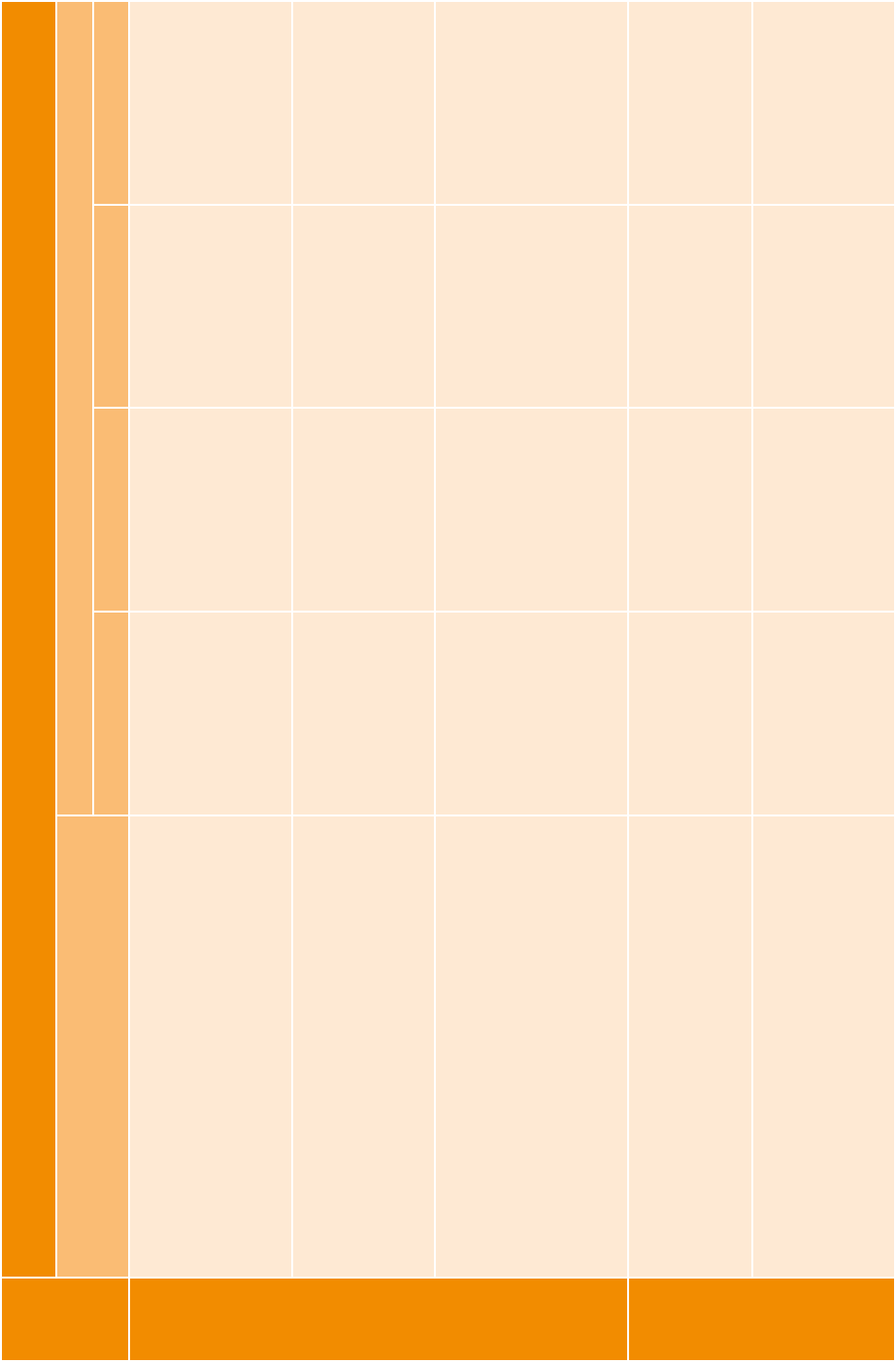

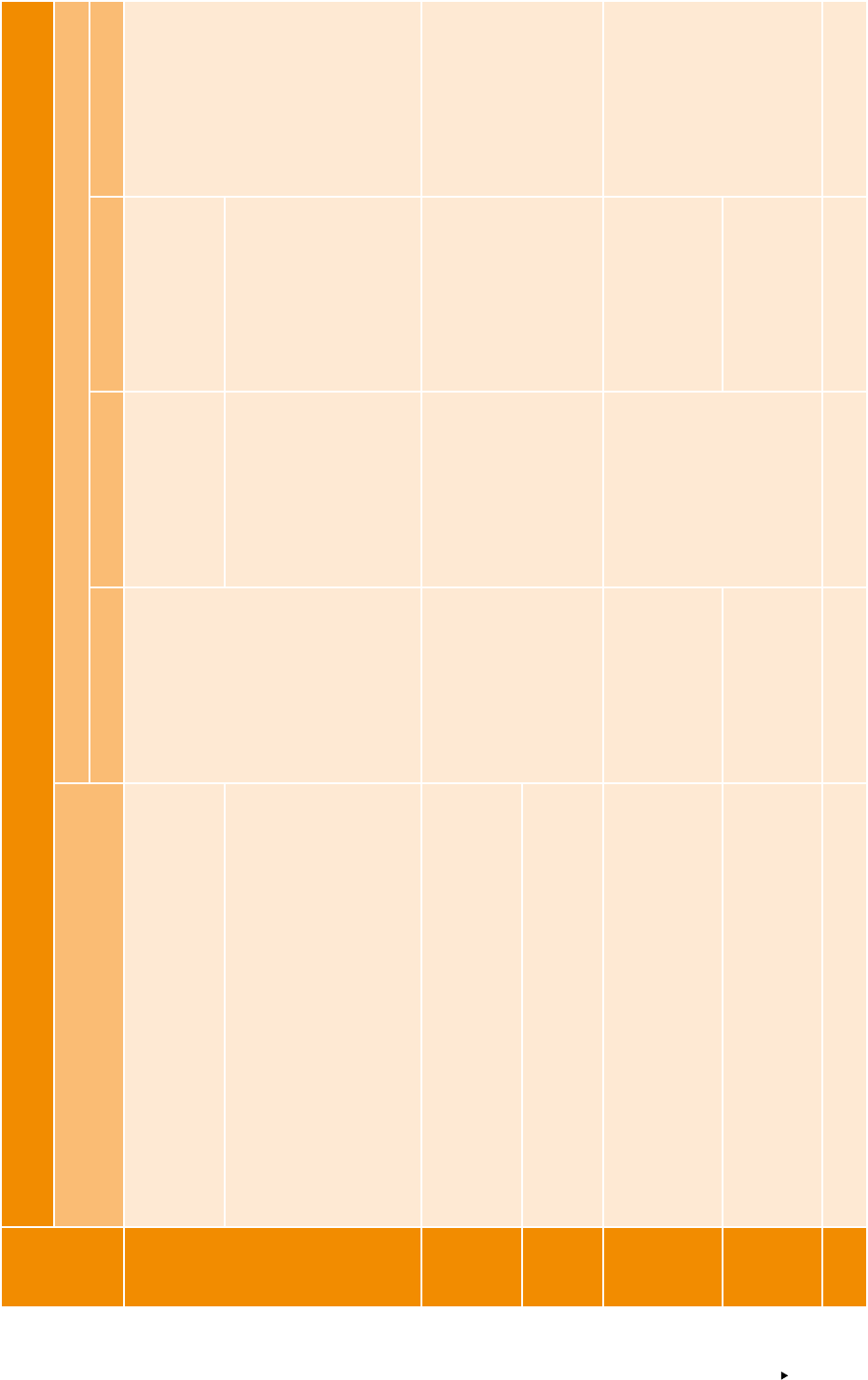

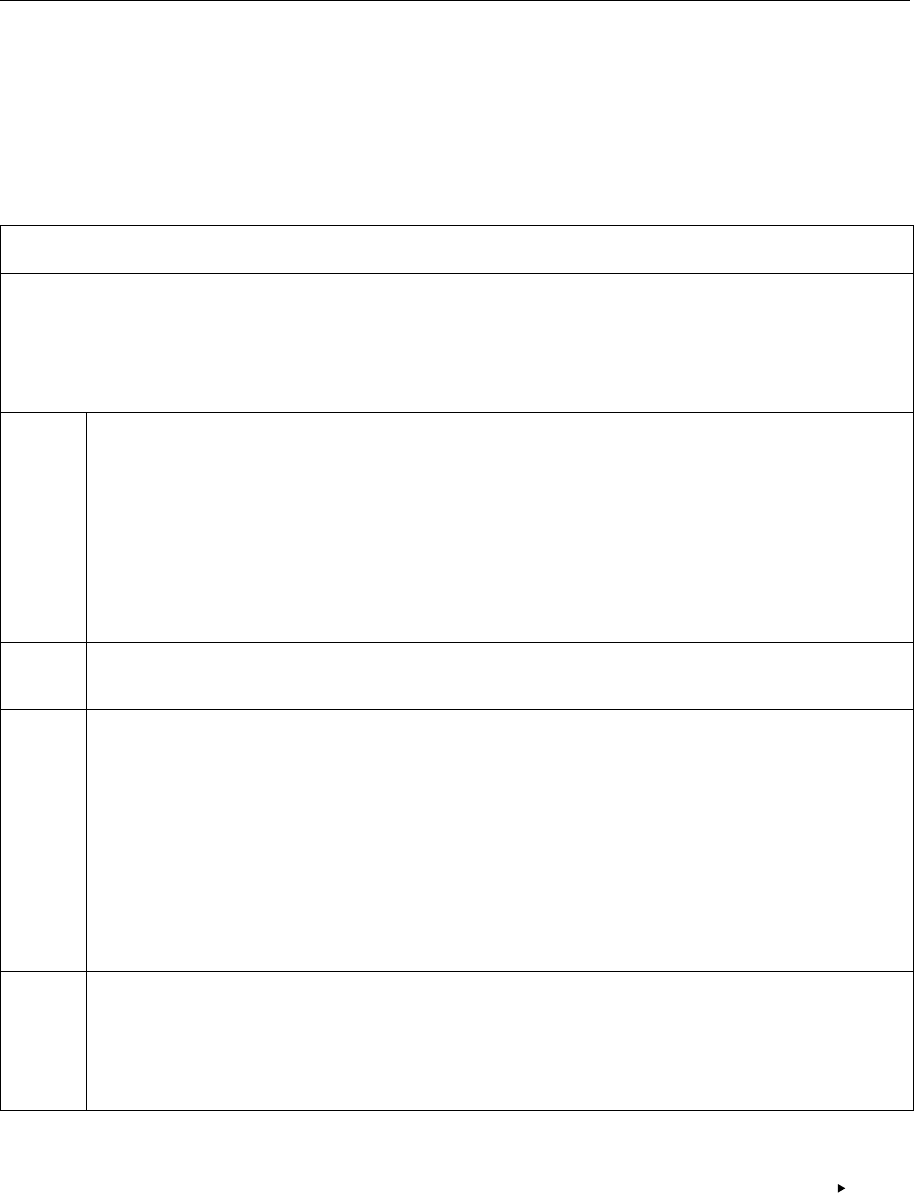

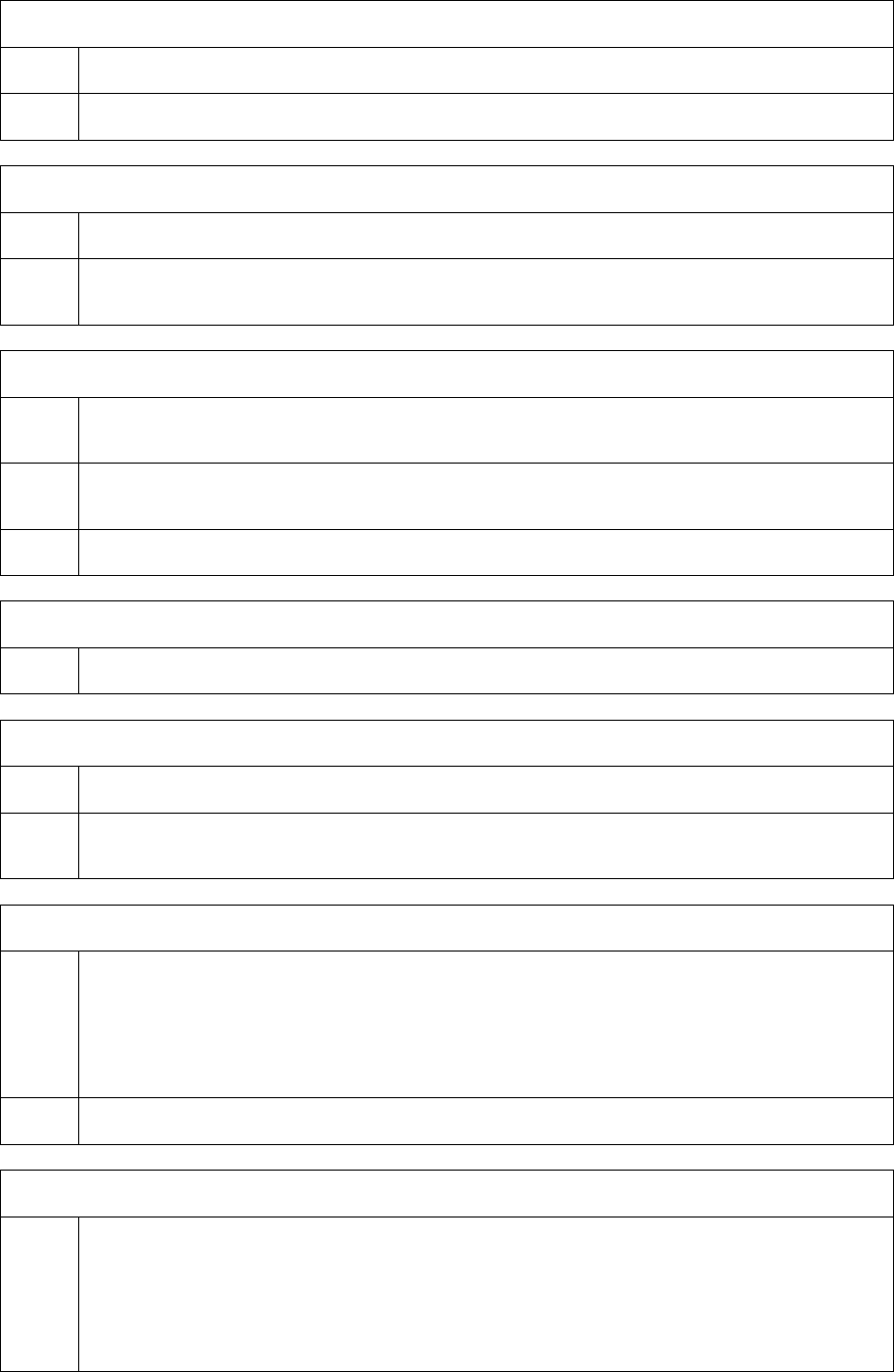

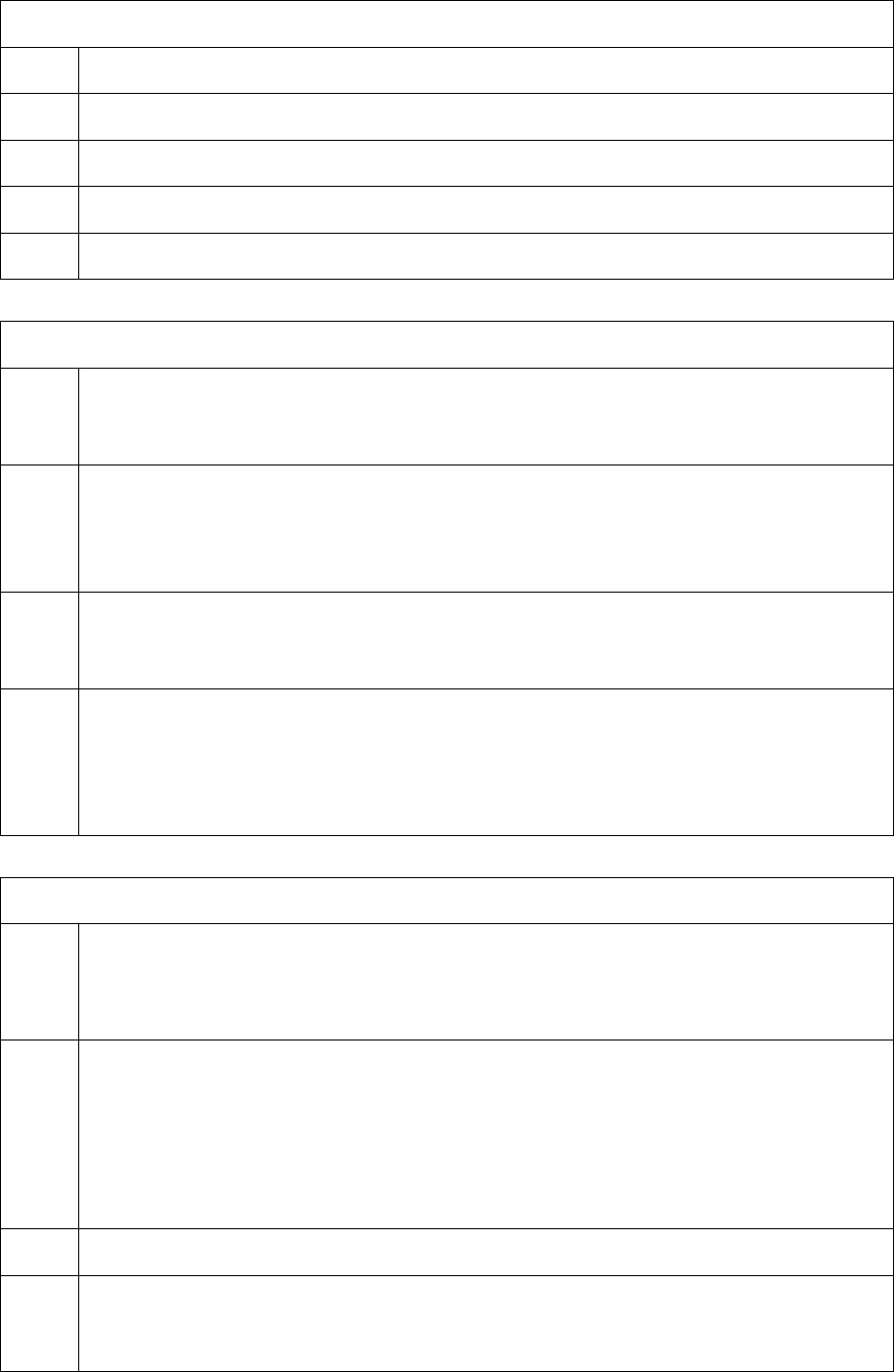

1.1. SUMMARY OF CHANGES TO THE ILLUSTRATIVE DESCRIPTORS

Table 2 summarises the changes to the CEFR illustrative descriptors and also the rationale for these changes. A

short description of the development project is given in Appendix 6, with a more complete version available in

the paper by Brian North and Enrica Piccardo: “Developing illustrative descriptors of aspects of mediation for

the CEFR”.

19

Table 2 – Summary of changes to the illustrative descriptors

What is

addressed in

this publication

Comments

Pre-A1

Descriptors for this band of prociency that is halfway to A1, mentioned at the beginning of

CEFR 2001 Section 3.5, are provided for many scales, including for online interaction.

Changes to

descriptors

published

in 2001

A list of substantive changes to existing descriptors appearing in CEFR 2001 Chapter 4 for

communicative language activities and strategies, and in CEFR 2001 Chapter 5 for aspects

of communicative language, is provided in Appendix 7. Various other small changes to

formulations have been made in order to ensure that the descriptors are gender-neutral and

modality-inclusive.

Changes to C2

descriptors

Many of the changes proposed in the list in Appendix 7 concern C2 descriptors included in the

2001 set. Some instances of highly absolute statements have been adjusted to better reect the

competence of C2 user/learners.

Changes

to A1-C1

descriptors

A few changes are proposed to other descriptors. It was decided not to “update” descriptors

merely because of changes in technology (e.g. references to postcards or public telephones).

The scale for “Phonological control” has been replaced (see below). The main changes

result from making the descriptors modality-inclusive, to make them equally applicable

to sign languages. Changes are also proposed to certain descriptors that refer to linguistic

accommodation (or not) by “native speakers”, because this term has become controversial since

the CEFR was rst published.

Plus levels

The description for plus levels (e.g. = B1+, B1.2) has been strengthened. Please see Appendix 1

and CEFR 2001 Sections 3.5 and 3.6 for discussion of the plus levels.

Phonology

The scale for “Phonological control” has been redeveloped, with a focus on “Sound articulation”

and “Prosodic features”.

Mediation

The approach taken to mediation is broader than that presented in the CEFR 2001. In addition

to a focus on activities to mediate a text, scales are provided for mediating concepts and

for mediating communication, giving a total of 19 scales for mediation activities. Mediation

strategies (5 scales) are concerned with strategies employed during the mediation process,

rather than in preparation for it.

Pluricultural

The scale “Building on pluricultural repertoire” describes the use of pluricultural competences

in a communicative situation. Thus, it is skills rather than knowledge or attitudes that are

the focus. The scale shows a high degree of coherence with the existing CEFR 2001 scale

“Sociolinguistic appropriateness”, although it was developed independently.

Plurilingual

The level of each descriptor in the scale “Building on plurilingual repertoire” is the functional

level of the weaker language in the combination. Users may wish to indicate explicitly which

languages are involved.

Specication

of languages

involved

It is recommended that, as part of the adaptation of the descriptors for practical use in a

particular context, the relevant languages should be specied in relation to:

- cross-linguistic mediation (particularly scales for mediating a text);

- plurilingual comprehension;

- building on plurilingual repertoire.

19. North B. and Piccardo E (2016), “Developing illustrative descriptors of aspects of mediation for the CEFR”, Education Policy Division,

Council of Europe, Strasbourg, available at https://rm.coe.int/16807331.

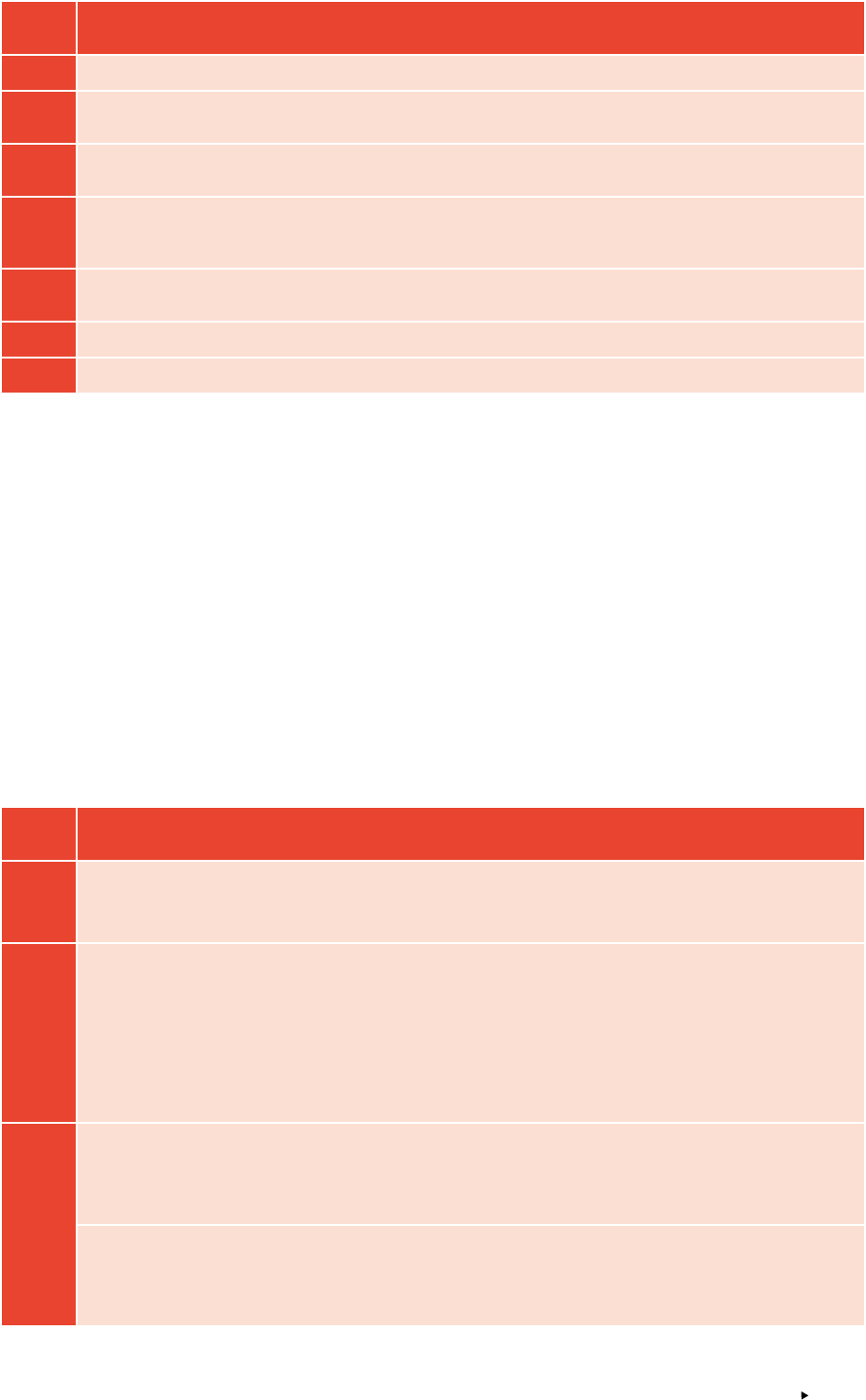

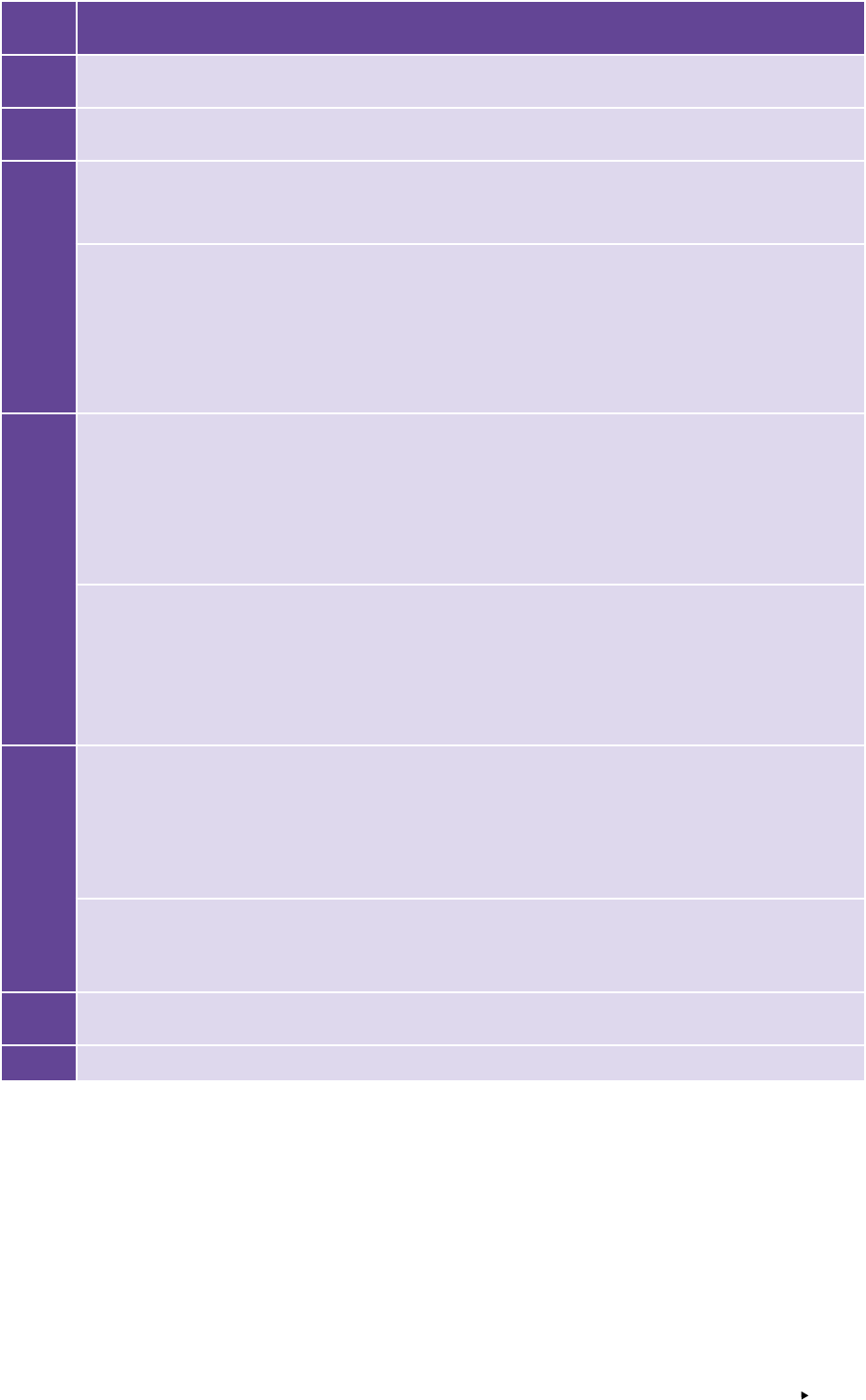

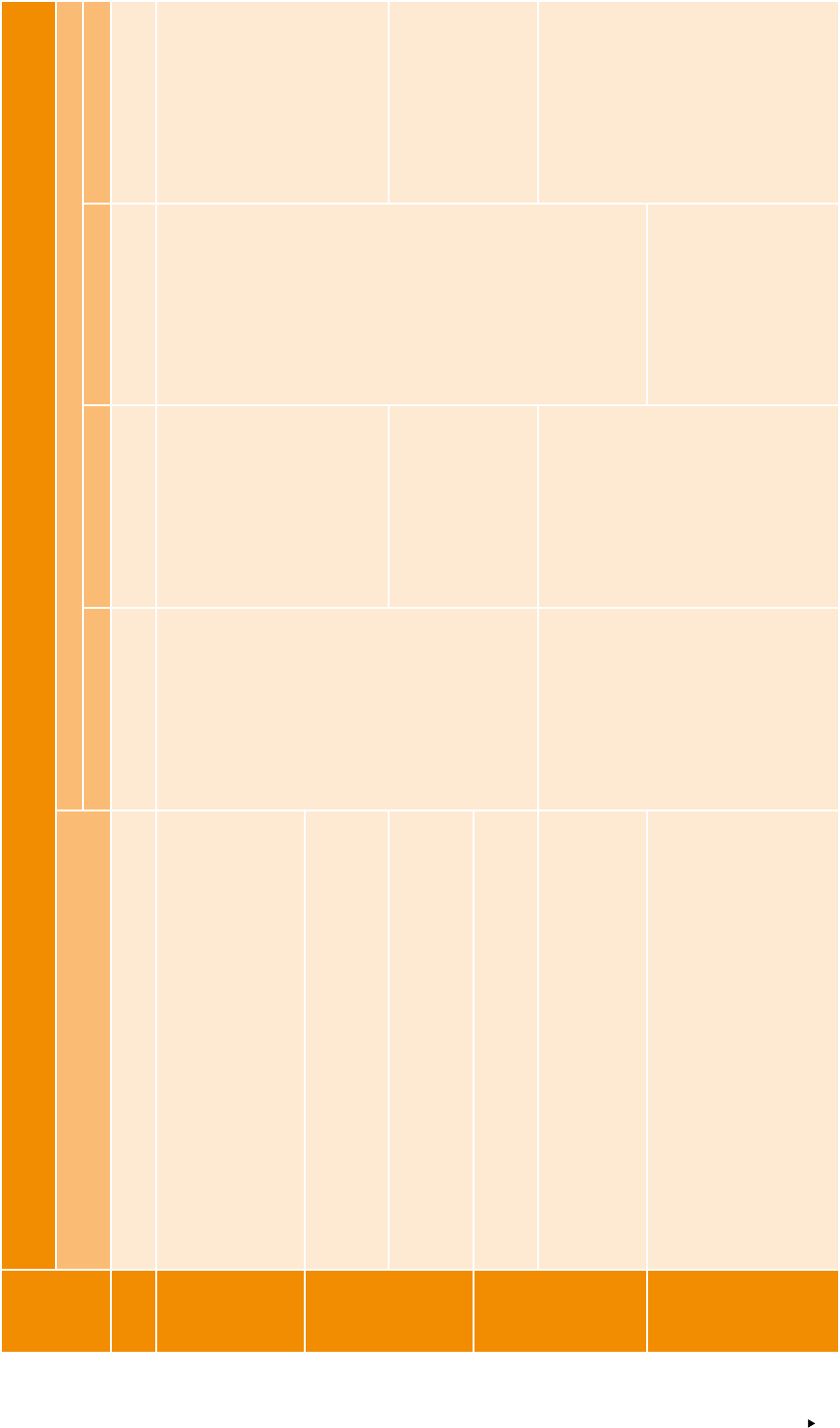

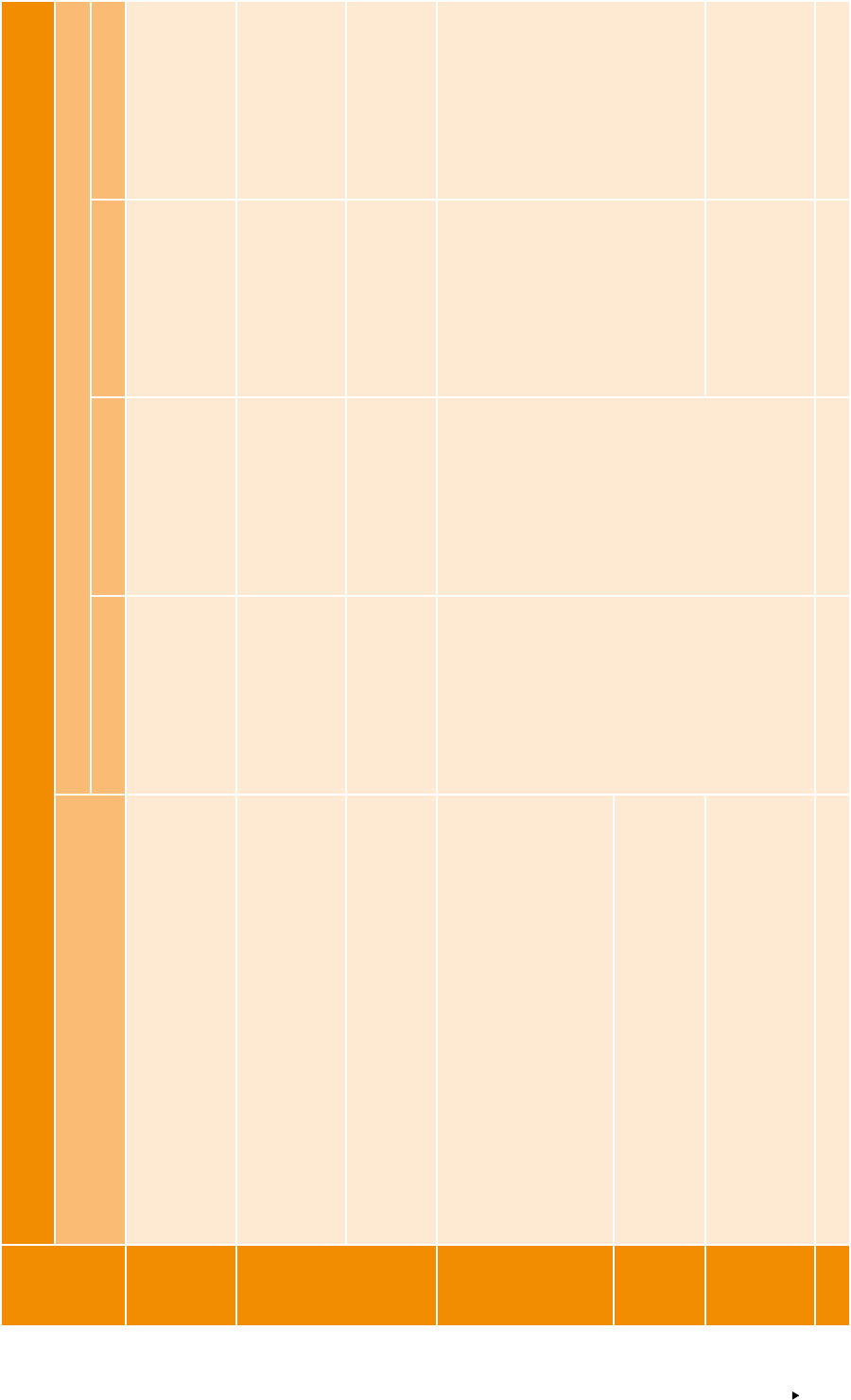

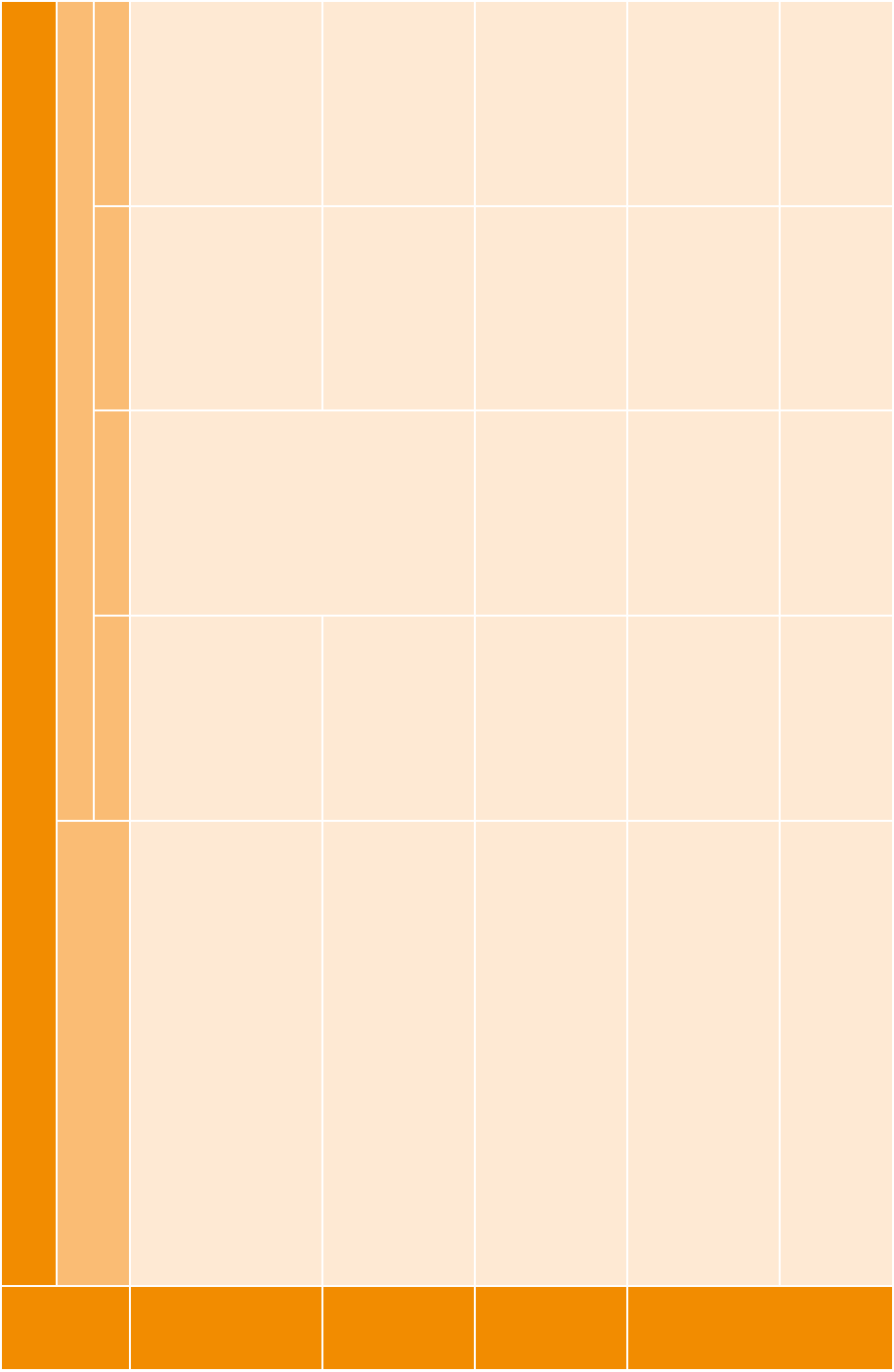

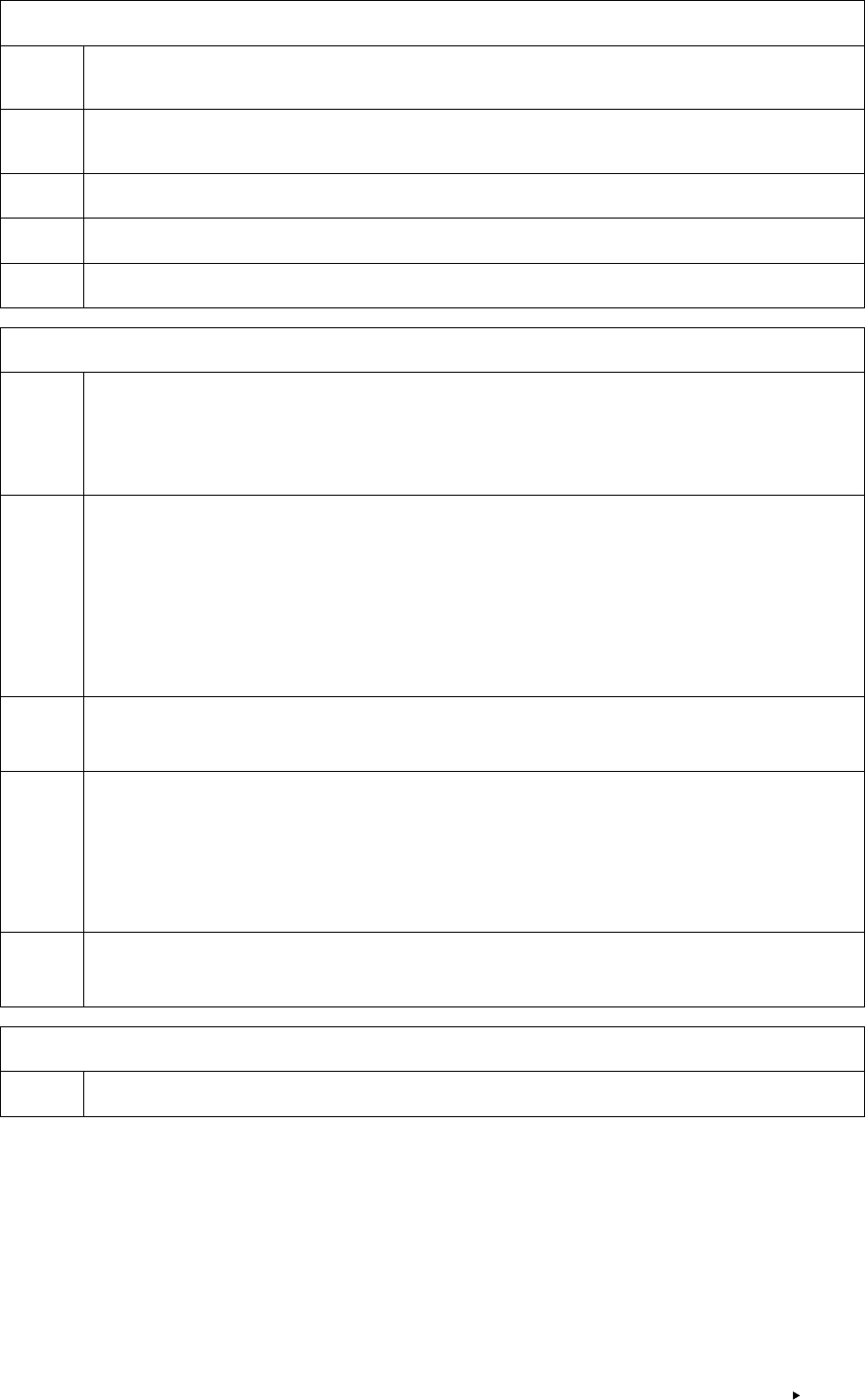

Introduction Page 25

What is

addressed in

this publication

Comments

Literature

There are three new scales relevant to creative text and literature:

- reading as a leisure activity (the purely receptive process; descriptors taken from other sets of

CEFR-based descriptors);

- expressing a personal response to creative texts (less intellectual, lower levels);

- analysis and criticism of creative texts (more intellectual, higher levels).

Online

There are two new scales for the following categories:

- online conversation and discussion;

- goal-oriented online transactions and collaboration.

Both these scales concern the multimodal activity typical of web use, including just checking

or exchanging responses, spoken interaction and longer production in live link-ups, using

chat (written spoken language), longer blogging or written contributions to discussion, and

embedding other media.

Other new

descriptor scales

New scales are provided for the following categories that were missing in the 2001 set, with

descriptors taken from other sets of CEFR-based descriptors:

- using telecommunications;

- giving information.

New descriptors

are calibrated to

the CEFR levels

The new descriptor scales have been formally validated and calibrated to the mathematical

scale from the original research that underlies the CEFR levels and descriptor scales.

Sign languages

Descriptors have been rendered modality-inclusive. In addition, 14 scales specically for

signing competence are included. These were developed in a research project conducted in

Switzerland.

Parallel project

Young learners

Two collations of descriptors for young learners from the European Language Portfolios (ELPs)

are provided: for the 7-10 and 11-15 age groups respectively. At the moment, no young learner

descriptors have been related to descriptors on the new scales, but the relevance for young

learners is indicated.

In addition to Chapter 2 “Key aspects of the CEFR for teaching and learning”, and the extended illustrative descriptors

included in this publication, users may wish to consult the following two fundamental policy documents related

to plurilingual, intercultural and inclusive education:

f

Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education (Beacco

et al. 2016a), which constitutes an operationalisation and further development of CEFR 2001 Chapter 8 on

language diversication and the curriculum;

f Reference framework of competences for democratic culture (Council of Europe 2018), the sources for which

inspired some of the new descriptors for mediation included in this publication.

Users concerned with school education may also wish to consult the paper “Education, mobility, otherness – The

mediation functions of schools”,

20

which helped the conceptualisation of mediation in the descriptor development

project.

20. Coste D. and Cavalli M. (2015) “Education, mobility, otherness – The mediation functions of schools”, Language Policy Unit, Council of

Europe, Strasbourg, available at https://rm.coe.int/16807367ee.

Page 27

21. Recommendation CM/Rec(2008)7 of the Committee of Ministers on the use of the Council of Europe’s Common European Framework

of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and the promotion of plurilingualism, available at https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.

aspx?ObjectId=09000016805d2fb1.

Chapter 2

KEY ASPECTS OF THE CEFR FOR

TEACHING AND LEARNING

The Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)

presents a comprehensive descriptive scheme

of language prociency and a set of Common

Reference Levels (A1 to C2) dened in illustrative

descriptor scales, plus options for curriculum design

promoting plurilingual and intercultural education,

further elaborated in the Guide for the development

and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and

intercultural education (Beacco et al. 2016a).

One of the main principles of the CEFR is the promotion

of the positive formulation of educational aims and

outcomes at all levels. Its “can do” denition of aspects

of prociency provides a clear, shared roadmap for

learning, and a far more nuanced instrument to gauge

progress than an exclusive focus on scores in tests and

examinations. This principle is based on the CEFR view

of language as a vehicle for opportunity and success

in social, educational and professional domains. This

key feature contributes to the Council of Europe’s

goal of quality inclusive education as a right of all

citizens. The Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers

recommends the “use of the CEFR as a tool for coherent,

transparent and eective plurilingual education in such

a way as to promote democratic citizenship, social

cohesion and intercultural dialogue”.

21

Background to the CEFR

The CEFR was developed as a continuation

of the Council of Europe’s work in language

education during the 1970s and 1980s. The

CEFR “action-oriented approach” builds on and

goes beyond the communicative approach

proposed in the mid-1970s in the publication

“The Threshold Level”, the rst functional/

notional specication of language needs.

The CEFR and the related European Language

Portfolio (ELP) that accompanied it were

recommended by an intergovernmental

symposium held in Switzerland in 1991. As

its subtitle suggests, the CEFR is concerned

principally with learning and teaching. It aims to

facilitate transparency and coherence between

the curriculum, teaching and assessment

within an institution and transparency

and coherence between institutions,

educational sectors, regions and countries.

The CEFR was piloted in provisional versions

in 1996 and 1998 before being published

in English (Cambridge University Press).

As well as being used as a reference tool by almost all member states of the Council of Europe and the European

Union, the CEFR has also had – and continues to have – considerable inuence beyond Europe. In fact, the

CEFR is being used not only to provide transparency and clear reference points for assessment purposes but

also, increasingly, to inform curriculum reform and pedagogy. This development reects the forward-looking

conceptual underpinning of the CEFR and has paved the way for a new phase of work around the CEFR, leading to

the extension of the illustrative descriptors published in this edition. Before presenting the illustrative descriptors,

however, a reminder of the purpose and nature of the CEFR is outlined. First, we consider the aims of the CEFR,

its descriptive scheme and the action-oriented approach, then the Common Reference Levels and creation of

proles in relation to them, plus the illustrative descriptors themselves, and nally the concepts of plurilingualism/

pluriculturalism and mediation that were introduced to language education by the CEFR.

Page 28 3 CEFR – Companion volume

2.1. AIMS OF THE CEFR

22. www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/reference-level-descriptions.

The CEFR seeks to continue the impetus that Council

of Europe projects have given to educational reform.

The CEFR aims to help language professionals further

improve the quality and eectiveness of language

learning and teaching. The CEFR is not focused on

assessment, as the word order in its subtitle – Learning,

teaching, assessment – makes clear.

In addition to promoting the teaching and learning

of languages as a means of communication, the CEFR

brings a new, empowering vision of the learner. The

CEFR presents the language user/learner as a “social

agent”, acting in the social world and exerting agency in

the learning process. This implies a real paradigm shift

in both course planning and teaching by promoting

learner engagement and autonomy.

The CEFR’s action-oriented approach represents a shift

away from syllabuses based on a linear progression

through language structures, or a pre-determined

set of notions and functions, towards syllabuses

based on needs analysis, oriented towards real-life

tasks and constructed around purposefully selected

notions and functions. This promotes a “prociency”

perspective guided by “can do” descriptors rather than

a “deciency” perspective focusing on what the learners

have not yet acquired. The idea is to design curricula

and courses based on real-world communicative needs,

organised around real-life tasks and accompanied

by “can do” descriptors that communicate aims to

learners. Fundamentally, the CEFR is a tool to assist

the planning of curricula, courses and examinations

by working backwards from what the users/learners

need to be able to do in the language. The provision

of a comprehensive descriptive scheme containing

illustrative “can do” descriptor scales for as many aspects

of the scheme as proves feasible (CEFR 2001 Chapters 4

and 5), plus associated content specications published

separately for dierent languages (Reference Level

Descriptions – RLDs)

22

is intended to provide a basis

for such planning.

Priorities of the CEFR

The provision of common reference points is

subsidiary to the CEFR’s main aim of facilitating

quality in language education and promoting a

Europe of open-minded plurilingual citizens. This

was clearly conrmed at the Intergovernmental

Language Policy Forum that reviewed progress

with the CEFR in 2007, as well as in several

recommendations from the Committee of

Ministers. This main focus is emphasised yet

again in the Guide for the development and

implementation of curricula for plurilingual and

intercultural education (Beacco et al. 2016a).

However, the Language Policy Forum also

underlined the need for responsible use of the

CEFR levels and exploitation of the methodologies

and resources provided for developing

examinations, and then relating them to the CEFR.

As the subtitle “learning, teaching, assessment”

makes clear, the CEFR is not just an assessment

project. CEFR 2001 Chapter 9 outlines many

dierent approaches to assessment, most of

which are alternatives to standardised tests.

It explains ways in which the CEFR in general,

and its illustrative descriptors in particular, can

be helpful to the teacher in the assessment

process, but there is no focus on language

testing and no mention at all of test items.

In general, the Language Policy Forum emphasised

the need for international networking and

exchange of expertise in relation to the CEFR

through bodies such as the Association of

Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) (www.alte.org),

the European Association for Language Testing

and Assessment (EALTA) (www.ealta.eu.org)

and Evaluation and Accreditation of Quality in

Language Services (Eaquals) (www.eaquals.org).

These aims were expressed in the CEFR 2001 as follows:

The stated aims of the CEFR are to:

f promote and facilitate co-operation among educational institutions in dierent countries;

f provide a sound basis for the mutual recognition of language qualications;

f

assist learners, teachers, course designers, examining bodies and educational administrators to situate

and co-ordinate their eorts.

(CEFR 2001 Section 1.4)

To further promote and facilitate co-operation, the CEFR also provides Common Reference Levels A1 to C2,

dened by the illustrative descriptors. The Common Reference Levels were introduced in CEFR 2001 Chapter 3

and used for the descriptor scales distributed throughout CEFR 2001 Chapters 4 and 5. The provision of a common

descriptive scheme, Common Reference Levels, and illustrative descriptors dening aspects of the scheme at

Key aspects of the CEFR for teaching and learning Page 29

the dierent levels, is intended to provide a common metalanguage for the language education profession in

order to facilitate communication, networking, mobility and the recognition of courses taken and examinations

passed. In relation to examinations, the Council of Europe’s Language Policy Division has published a manual

for relating language examinations to the CEFR,

23

now accompanied by a toolkit of accompanying material and

a volume of case studies published by Cambridge University Press, together with a manual for language test

development and examining.

24

The Council of Europe’s ECML has also produced Relating language examinations

to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR) – Highlights

from the Manual

25

and provides capacity building to member states through its RELANG initiative.

26

However, it is important to underline once again that the CEFR is a tool to facilitate educational reform projects,

not a standardisation tool. Equally, there is no body monitoring or even co-ordinating its use. The CEFR itself

states right at the very beginning:

One thing should be made clear right away. We have NOT set out to tell practitioners what to do, or how to do it. We

are raising questions, not answering them. It is not the function of the Common European Framework to lay down the

objectives that users should pursue or the methods they should employ. (CEFR 2001, Notes to the User)

2.2. IMPLEMENTING THE ACTIONORIENTED APPROACH

The CEFR sets out to be comprehensive, in the sense that it is possible to nd the main approaches to language

education in it, and neutral, in the sense that it raises questions rather than answering them and does not

prescribe any particular pedagogic approach. There is, for example, no suggestion that one should stop teaching

grammar or literature. There is no “right answer” given to the question of how best to assess a learner’s progress.

Nevertheless, the CEFR takes an innovative stance in seeing learners as language users and social agents, and

thus seeing language as a vehicle for communication rather than as a subject to study. In so doing, it proposes

an analysis of learners’ needs and the use of “can do” descriptors and communicative tasks, on which there is a

whole chapter: CEFR 2001 Chapter 7.

23. Council of Europe (2009), “Relating Language Examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages:

Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR) – A Manual”, Language Policy Division, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, available at https://

rm.coe.int/1680667a2d.

24. ALTE (2011), “Manual for language test development and examining – For use with the CEFR”, Language Policy Division, Council of

Europe, Strasbourg, available at https://rm.coe.int/1680667a2b.

25. Noijons J., Bérešová J., Breton G. et al. (2011), Relating language examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR) – Highlights from the Manual, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, available at:

www.ecml.at/tabid/277/PublicationID/67/Default.aspx.

26. Relating language curricula, tests and examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference (RELANG): https://relang.ecml.at/.

The methodological message of the CEFR is that

language learning should be directed towards

enabling learners to act in real-life situations,

expressing themselves and accomplishing tasks of

dierent natures. Thus, the criterion suggested for

assessment is communicative ability in real life, in

relation to a continuum of ability (Levels A1-C2). This

is the original and fundamental meaning of “criterion”

in the expression “criterion-referenced assessment”.

Descriptors from CEFR 2001 Chapters 4 and 5 provide

a basis for the transparent denition of curriculum

aims and of standards and criteria for assessment,

with Chapter 4 focusing on activities (“the what”) and

Chapter 5 focusing on competences (“the how”). This is

not educationally neutral. It implies that the teaching

and learning process is driven by action, that it is action-

oriented. It also clearly suggests planning backwards

from learners’ real-life communicative needs, with

consequent alignment between curriculum, teaching

and assessment.

A reminder of CEFR 2001 chapters

Chapter 1: The Common European Framework

in its political and educational context

Chapter 2: Approach adopted

Chapter 3: Common Reference Levels

Chapter 4: Language use and the

language user/learner

Chapter 5: The user/learner’s competences

Chapter 6: Language learning and teaching

Chapter 7: Tasks and their role in language teaching

Chapter 8: Linguistic diversication

and the curriculum

Chapter 9: Assessment

Page 30 3 CEFR – Companion volume

At the classroom level, there are several implications of implementing the action-oriented approach. Seeing

learners as social agents implies involving them in the learning process, possibly with descriptors as a means of

communication. It also implies recognising the social nature of language learning and language use, namely the

interaction between the social and the individual in the process of learning. Seeing learners as language users

implies extensive use of the target language in the classroom – learning to use the language rather than just

learning about the language (as a subject). Seeing learners as plurilingual, pluricultural beings means allowing

them to use all their linguistic resources when necessary, encouraging them to see similarities and regularities as

well as dierences between languages and cultures. Above all, the action-oriented approach implies purposeful,

collaborative tasks in the classroom, the primary focus of which is not language. If the primary focus of a task is

not language, then there must be some other product or outcome (such as planning an outing, making a poster,

creating a blog, designing a festival or choosing a candidate). Descriptors can be used to help design such tasks

and also to observe and, if desired, to (self-)assess the language use of learners during the task.

Both the CEFR descriptive scheme and the action-oriented approach put the co-construction of meaning (through

interaction) at the centre of the learning and teaching process. This has clear implications for the classroom. At

times, this interaction will be between teacher and learner(s), but at times, it will be of a collaborative nature,

between learners themselves. The precise balance between teacher-centred instruction and such collaborative

interaction between learners in small groups is likely to reect the context, the pedagogic tradition in that

context and the prociency level of the learners concerned. In the reality of today’s increasingly diverse societies,

the construction of meaning may take place across languages and draw upon user/learners’ plurilingual and

pluricultural repertoires.

2.3. PLURILINGUAL AND PLURICULTURAL COMPETENCE

The CEFR distinguishes between multilingualism (the coexistence of dierent languages at the social or individual

level) and plurilingualism (the dynamic and developing linguistic repertoire of an individual user/learner).

Plurilingualism is presented in the CEFR as an uneven and changing competence, in which the user/learner’s

resources in one language or variety may be very dierent in nature from their resources in another. However,