St. Cloud State University

theRepository at St. Cloud State

Culminating Projects in English Department of English

12-2017

Use of English Articles by Korean Students

Minhui Choi

St. Cloud State University

Follow this and additional works at: h6ps://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds

5is 5esis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact

rswexelbaum@stcloudstate.edu.

Recommended Citation

Choi, Minhui, "Use of English Articles by Korean Students" (2017). Culminating Projects in English. 109.

h6ps://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/109

1

Use of English Articles by Korean Students

by

Minhui Choi

A Thesis

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of

St. Cloud State University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master of Arts in

Teaching English as a Second Language

December 2017

Thesis Committee:

John Madden, Chairperson

James Robinson

Kyounghee Seo

2

Abstract

Correct use of English articles is a challenge for many English learners. English learners

of various native language backgrounds make frequent mistakes when it comes to choosing

appropriate articles to denote definiteness in English. Korean language falls into a language

group that lacks an overt article system, which causes many Korean English learners to struggle

with English articles. This study investigates the use of English articles by Korean students who

are studying in an American college using English as a second language. An oral translation task

of a Korean story into English, which involved voice recording, transcribing those recordings

and then calculating each English article use, was employed to examine thirty-five Korean

participants’ English article use. The results demonstrate a few features in Korean students’

article use:

(1) Korean learners follow the accuracy pattern of the → a/an → zero article in descending order

of proficiency; (2) no significant statistical evidence was found between the accuracy of article

use and length of stay in English speaking counties; (3) Korean students presented comparatively

more accurate article use in definite contexts than in indefinite contexts suggesting that correct

article use in indefinite contexts is more problematic for them compared to definite contexts; and

(4) when they make mistakes, subjects misused the more than zero article in indefinite contexts

where a/an I s required, while misusing zero article more than a/an in definite contexts where

the is required. Both in definite and indefinite contexts, participants used the the most and a/an

the least.

3

Acknowledgements

I’d like to express my sincere gratitude to all the Korean students who sacrificed their

time and energy to participate in my project, which was very challenging to them. Without their

contribution, this research would not have been possible. I am also deeply grateful for my thesis

committee members: Dr. John Madden, my thesis advisor, for his patience, systematic

instructions, and insightful comments throughout this research; Dr. James Robinson for his

guidance and encouragement as my academic advisor; and Dr. Kyounghee Seo for introducing

me to these wonderful graduate programs at St Cloud State University and for her continuous

support. Finally, I would like to thank my family in Korea for their long-distance loving support

and my husband and best friend, Benjamin Lambertson, for his limitless support and

encouragement throughout my graduate study.

4

Table of Contents

Page

List of Tables ................................................................................................................... 6

List of Figures .................................................................................................................. 7

Chapter

1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 8

2. Literature Review................................................................................................. 10

English Articles .............................................................................................. 10

Korean Language ........................................................................................... 14

Different Perspectives on the Role of Native Languages in SLA.................. 18

Research on ESL Students’ English Article Use ........................................... 21

3. Methodology ........................................................................................................ 24

Research Questions ........................................................................................ 24

Participants ..................................................................................................... 25

Description of Data Collection Instruments .................................................. 27

Procedures ...................................................................................................... 29

Data Coding ................................................................................................... 30

Coding for TLU ............................................................................................. 32

Coding for Article Use in Definite and Indefinite Contexts .......................... 33

4. Results and Discussions ....................................................................................... 36

Different Transcripts in Various Lengths ...................................................... 36

TLU Scores, Order of Accuracy, and Length of Stay

in English Speaking Countries ................................................................. 38

5

Chapter Page

Article Use in Definite and Indefinite Contexts ............................................ 44

5. Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications ......................................................... 51

Limitations and Further Research .................................................................. 54

References ........................................................................................................................ 56

Appendices

A. The “Gold Ax and Silver Ax” Folk Tale ................................................................ 59

B. English Version of the Folk Tale ............................................................................ 61

C. Background Questionnaire...................................................................................... 63

6

List of Tables

Table Page

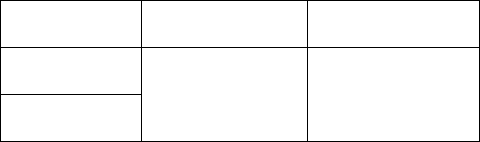

1. Article-grouping by Definiteness (English) ........................................................ 12

2. Article-grouping by Specificity (Samoan) ........................................................... 13

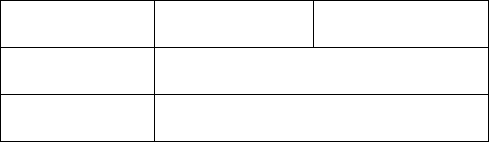

3. Hierarchy of Difficulty ........................................................................................ 19

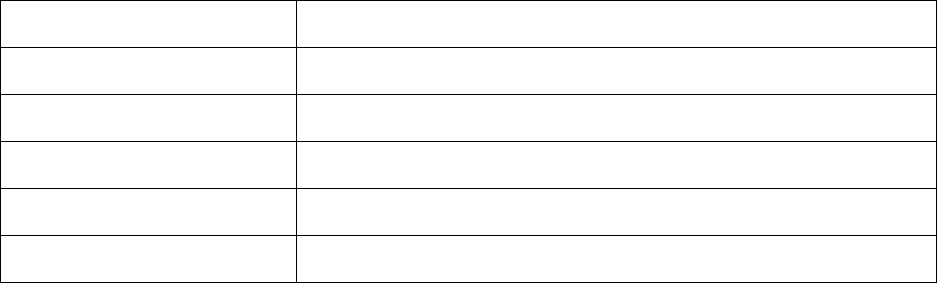

4. Characteristics of Participants.............................................................................. 25

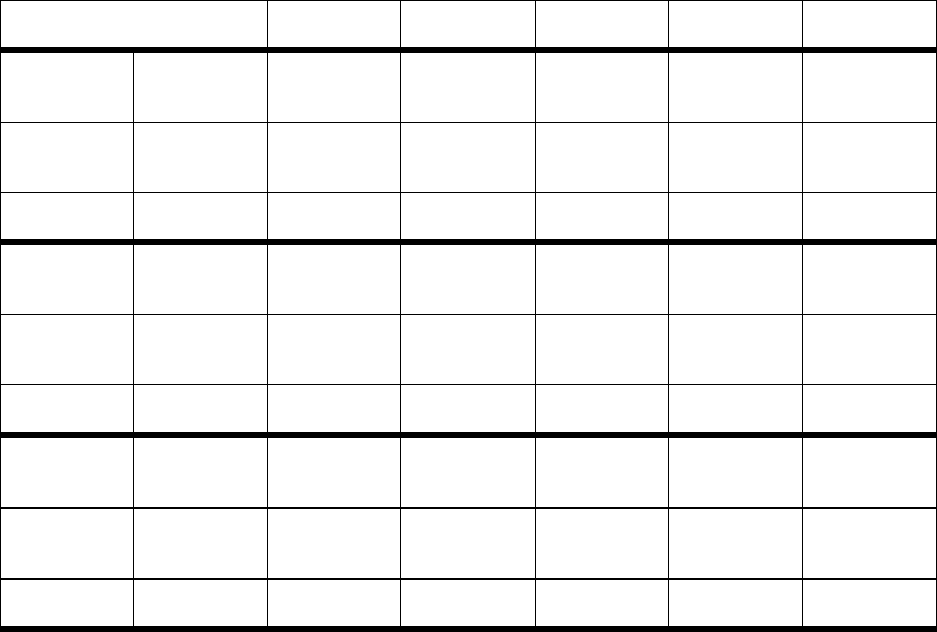

5. Subject #1 TLU Scores ........................................................................................ 33

6. Word Counts and TLU Scores for Three Selected Subjects ................................ 37

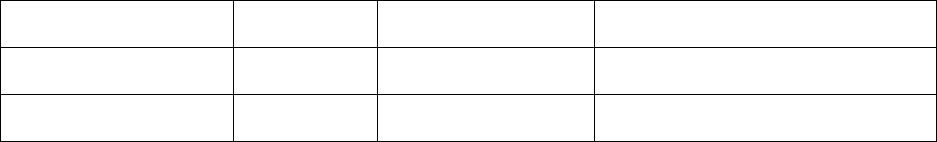

7. TLU Scores of Three Groups ............................................................................... 39

8. ANOVA Test Results .......................................................................................... 42

9. Average Stay in English Speaking Countries ...................................................... 43

10. Article Use in Indefinite Context ......................................................................... 44

11. Article Use in Definite Context ........................................................................... 44

7

List of Figures

Figure Page

1. Three Groups’ TLU Scores for the, a/an, and zero article ................................. 40

2. Correct Use of a/an in Indefinite Context and the in Definite Contexts ............. 46

3. Incorrect Use of the and zero article in Indefinite Contexts ................................ 47

4. Incorrect Use of a/an and zero article in Definite Contexts ................................ 48

5. Each Article Use of Total Group in Indefinite and Definite Contexts................. 49

8

Chapter 1: Introduction

Making errors with article use is one of the most common occurrences when it comes to

learning English. For language learners whose native languages do not have articles, finding an

appropriate article to use in a certain speaking or writing context can be difficult. There is no

article system in many Asian, Slavic, and African languages (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman

1999). Even though English articles take up a small part of English grammar, they are one of the

most commonly used words in conversations. English articles are difficult to learn by many

English learners. Even a learner who has studied for a long time often struggles to choose an

appropriate article to use in conversation.

Not only is learning English articles difficult, but teaching English articles to students

whose native language does not include articles can be even more difficult. Yamada and

Matsuura (1982) stated that native English teachers found that the way students choose an article

to use does not go well with the existing English language system. Many ESL students tend to

choose an article arbitrarily. ESL learners commonly omit articles regardless of definite or

indefinite contexts, use a/an for the or vice versa and apply articles in the wrong context when

they speak English. According to Ionin, Ko, and Wexler (2004), learners sometimes misinterpret

the use of the and a/an because they apply definiteness or specificity incorrectly.

Korean falls into the group of languages where articles do not exist. Many Korean

English speakers have difficulty learning how to use English articles appropriately because it is a

new concept for them. According to Myers (1992), Korean learners often make errors in their

oral usage of English by omitting proper articles.

9

The English article functions as a marker to designate the definiteness or indefiniteness of

a noun. When the is used in front of a noun, the noun is considered definite. The can also signal

old or previously remarked information. The singular indefinite article a/an is followed by a

noun which is indefinite and can be used to indicate new information.

Some researchers divide articles into two features: definiteness and specificity.

According to Ko, Ionin, and Wexler (2009), the shared understanding between speakers and

listeners is referred to as definiteness, and the information that only the speaker knows is referred

to as specificity. Even though English article selection is decided by definiteness, Korean

English learners tend to choose an article based on specificity as well as definiteness (Ionin, Ko,

& Wexler, 2004).

Korean language has its own way to express definiteness or specificity and the people

tend to rely upon demonstratives, postpositions, and context rather than articles. Explicit

denotation of definiteness or specificity is often unnecessary because they can be imbedded into

the context of a sentence. This leads many Korean English learners to miss an article use even

when an article is necessary in English. Therefore, it is crucial to comprehend what challenges

Korean English speakers might have when they try to learn and utilize English articles.

10

Chapter 2: Literature Review

English Articles

According to Master (1996), English necessitates use of determiners for nouns, so a noun

phrase should be comprised of at least a determiner and a following noun. Articles are one of the

main determiners in the English grammar system. The English article system has three types of

articles: a/an, the and the zero article. The zero article can be symbolized as Ø. Master (1996)

stated that articles play two main roles: classification and identification. If someone talks about a

random object which belongs to a certain group, an indefinite article a/an or Ø is used. If a noun

is identified and the hearer and listener understand what the noun designates, the definite article

the is used.

Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) proposed that article use essentially depends

on the context rather than the structure of a sentence. Choosing an appropriate article for a noun

heavily depends on the knowledge shared between interlocutors in conversations. Therefore, the

definite article the is used for a specific noun which is being argued between the speaker and the

listener, and indefinite articles are used for a noun whose identity is not specific to conversation

participants (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999). It is essential for ESL students to learn

getting clues from ‘pragmatic/discourse knowledge’ to use articles appropriately (Park, 2013).

When a noun is introduced to communication, indefinite articles are used since its

identity is not specific yet. However, when the speaker mentions the noun again, the speaker and

the listener understand which object the speaker is talking about. The identity of the noun is

specific now, so the definite article is used for the second mention of the noun. Celce-Murcia

and Larsen-Freeman (1999) called this “first mention → subsequent mention principle” (p. 282).

11

In most conversation situations, the use of articles is determined by context, not by sentence

structure.

In general, indefinite articles are used for nonspecific nouns and the zero articles are

employed for plural nouns. Proper nouns like names of people or locations take the zero article

with a few exceptions. Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) classified the use of the into

three groups based on how a referent is located by the speaker and listener. They are “a

situational-cultural, a textual, and situational basis” (p. 279). According to Celce-Murcia and

Larsen-Freeman (1999), the situational-cultural basis includes “general cultural use (the sun, the

earth), perceptual situational use (Pass me the salt), immediate situational use (Don’t go there.

The dog will bite you), local use for general knowledge (the church, the pub), and local use for

specific knowledge (in the town of Halifax)” (p. 279). The textual use of the has the following

subsets: anaphoric use (previous reference), deductive anaphoric use (preceding reference of a

schematically-related notion) and cataphoric use (following discussion of something related)

(Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999). Situational use of the contains usage with post-

modifiers (relative clauses, prepositional phrases) and usage with ranking determiners and

adjectives (the first and the next) (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999).

Articles can be decided by two parameters: definiteness and specificity. According to

Ionin et al. (2004), definiteness denotes that the speaker and the listener share the meaning of a

noun in a context, and specificity means only the speaker knows about a noun which is

mentioned. The definitions for definiteness and specificity are described by Ionin et al. (2004) as

follows:

12

1. Definiteness

If a Determiner Phrase (DP) of the form [DNP] is [+definite], then the speaker and

hearer presuppose the existence of a unique individual in the set denoted by the NP.

2. Specificity

If a Determiner Phrase (DP) of the form [D NP] is [+specific], then the speaker

intends to refer to a unique individual in the set denoted by the NP and considers this

individual to possess some noteworthy property (Ionin et al., 2004, p. 5).

English is one of the languages in which articles are selected by definiteness. English

articles are divided into two group: definite article the and indefinite article a/an. According to

Ionin et al. (2004), there is no indicator for marking specificity in the English article system.

Unlike in English, specificity is a main parameter that decides articles in Samoan language

(Ionin et al., 2008). Samoan language has articles le for specific contexts and se for non-specific

contexts but no article to express definiteness. The following tables, Table 1 and Table 2, show

the difference of the article system between English and Samoan.

Table 1

Article-grouping by Definiteness (English)

(Ionin, Zubizarreta, & Maldonado, 2008, p. 558)

context

+definite

-definite

+specific

the

a

-specific

13

Table 2

Article-grouping by Specificity (Samoan)

(Ionin et al., 2008, p. 559)

According to Ionin et al. (2004), speakers of languages that do not have articles

“fluctuate” between definiteness and specificity when choosing English articles. In Kim and

Lakshmanan’s (2009) study, Korean English learners who do not have articles in their native

language, tend to choose an article based on specificity as well as definiteness even though

English article selection is decided by definiteness (Kim & Lakshmanan, 2009).

However, English learners with articles in their native language show a different

tendency in their English article use. Researchers attribute this to positive transfer of article use

from Spanish to English. According to Schönenberger (2014), ESL learners whose native

languages have articles “transfer the parameter value from their L1 (native language) to L2

(second language) English” (p. 77).

The article systems in Spanish and German are based on definiteness as in English. In

the study of Ionin et al. (2008), English learners with a Spanish L1 background showed higher

accuracy with English article use than Russian English students who do not have an article

system in their native language. Schönenberger (2014) reported that German English learners

also did not show much difficulty using English articles, compared to Russian students. It seems

that students’ native language’s similarity to English leads to positive transfer from L1 to L2.

context

+definite

-definite

+specific

Le

-specific

Se

14

The Korean Language

It is essential to discuss some characteristics of the Korean Language system to

understand why Korean English learners make frequent errors with use of English articles.

Many languages express definiteness or indefiniteness using their own unique system such as

articles in English. Languages without a distinct article system like English still have their own

methods to denote definiteness. Schönenberger (2014) argued that in languages which do not

have an article system, definiteness is addressed by using ‘the word order,’ the morphological

case,’ ‘the aspectual system,’ ‘demonstratives,’ ‘possessives’ or ‘numerals.’

A common misunderstanding about the Korean language is that it does not have a system

expressing definiteness or even the concept of definiteness. However, nouns do not solely

depend on article systems to express definiteness. Kim (2012) insisted that Korean conveys

definiteness and indefiniteness, which is universal across languages, but which does it differently

from English. Jun (2013) also stated that the lack of an article system in the Korean language

does not mean that it cannot convey definiteness. According to Jun, it is possible to translate

English into Korean without damaging this information of definiteness.

In many cases, nouns in Korean do not have explicit determiners associated with them;

therefore, it is common to see a noun phrase that has solely a noun. Jun (2013) argued that in

Korean, “bare noun phrases” have an immense role in noun phrases because they deliver

multiple meanings. According to Jun, a bare noun (i.e.

학생

(hak-saeng)), which means student

in English, can deliver four different meanings, such as “a student, the student, students and the

students” (p. 2).

15

According to Ellis (1997), Interlingual/intralingual transfer occurs when someone’s

native language does not have a certain feature of a target language. The Korean language does

not have an overt article system, which puzzles Korean English learners in choosing an article to

use. One might wonder how Koreans deliver the meaning of definiteness in their language. Jun

(2013) insisted that the Korean language has its own system to signal those language properties

and does not have any trouble with delivering definiteness or specificity between the speaker and

listener.

One of the common means Koreans employ to signal definiteness is using

demonstratives. Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) argued that the definite article the

originated from demonstratives such as that. Koreans use a few demonstrative words to indicate

definiteness in conversations. The most frequently used demonstratives in Korean are

저

(jeo),

이

(yi) and

그

(gu). According to Kang (2012),

저

(jeo) is used when the object is far from the

speaker,

그

(gue) when the object is medial to the speaker, and

이

(yi) for the object which is near

to the speaker.

1. 나는 저 곳에 갔습니다. (I went to that place.)

Na-nun jeo gou-se Gatseumnida.

I that place-to went

2. 나는 이 곳에 갔습니다. (I went to this place.)

Na-nun yi gou-se Gatseumnida.

I this place-to went

In (1), the Korean demonstrative

저

(jeo) means English demonstrative that, and

이

(Yi)

in (2) means this in English. In Korean, demonstratives are more actively used because they do

16

not have articles. The last demonstrative to be discussed is

그

(gue), which is unique, compared

to other demonstratives.

3. 나는 그 곳에 갔습니다. (I went to that place.)

Na-nun geu gou-se Gatseumnida.

I the place-to went

In (3), the demonstrative

그

(geu) is used to express definiteness. Even though its

meaning is similar to Korean demonstrative

저

(jeo) used in (1),

그

(geu) and

저

(jeo) do not have

the same meaning. Kang (2012) argued that

그

(gue) is different from other demonstratives

because it acts like the definite article (the) in a certain context. In many cases, English article

the is translated into Korean as

그

(gue.). Therefore, some Korean English speakers tend to

overuse the when they speak English.

According to Jun (2013), as well as

이

(yi),

그

(gue), and

저

(jeo),

어떤

(eoteun) or

한

(han) can denote definiteness/specificity. The meaning of

어떤

(eoteun) or

한

(han) is close to

the English word a certain.

In many cases, Koreans get information on definiteness or indefiniteness from the context

of the conversation. According to Lee (1992), “the interpretation of nouns regarding

indefiniteness and definiteness largely depends on context in Korean” (p. 328). Jun (2013) also

stated that definiteness or specificity in Korean language can be cued from the previous

conversation and noun phrases, which if mentioned in the previous context, can be omitted

without a problem. This kind of omission is common in Korean conversations, but it does not

17

confuse communication because a lot of seemingly missing information can be inferred from the

context.

Koreans do not rely upon articles to introduce a new referent in a conversation. They

rather leave out any markers which denote definiteness or indefiniteness.

4. 누가 왔니? 아이가 왔어요. (Who came? A/the kid came)

Nuga watni? Ayi-ga watseoyo.

Who came? Kid came.

In (4), the word ayi (kid) was used without an article. In this conversation, the speaker

and the listener share the information of definiteness through the context. There is no need to

use definite or indefinite articles to deliver information in this Korean conversation because

definiteness is conferred from the context alone, unlike in English, where definite articles are

used.

One of the unique language systems in Korean is postpositions. Postpositions are added

to nouns, assigning those nouns cases such as subjects, objects, or complements. One interesting

thing about these postpositions is that they can designate definiteness to nouns. According to Jun

(2013), postpositions have a critical influence on the meaning of nouns to which they are

attached.

5. 고양이는 매우 빨라요. (Cats are very fast.)

Goyangyi-neun maewoo palayo.

Cat very fast

18

6. 고양이가 매우 빨라요. (The cat is very fast.)

Goyangyi-ga maewoo palayo.

Cat very fast

Both

는

(neun) and

가

(ga) in (5) and (6) are postpositions which assign the subject case

to the noun

고양이

Goyanyi (cat). However, the meaning of cat in (5), of which the postposition

는

(neun) is put at the end, is indefinite and it implies the generic meaning of a cat, while the

meaning of cat in (6) with the postposition

가

(ga) is definite, and refers to a specific cat that the

speaker and the listener understand together. Jun (2013) insisted that it is critical to consider

postpositions when discussing the meaning of noun phrases in Korean.

Different Perspectives on the Role of

Native Languages in SLA

The influence of native languages on second language acquisition (SLA) has been an

incessantly argued topic for a long time in the field of SLA. Even though the degrees of

influence that the native language has on second language development are considered to be

various, according to different scholars, the position of learners’ first language in second

language acquisition is regarded as being quite steadfast.

Behaviorism, which prevailed in 1950s and 1960s, is a psychological learning theory that

proposes a strong role of native language in second language acquisition. In behaviorism,

language learning is deeply associated with native languages and the influence of native

languages on second language learning is called ‘transfer’ (Gass, 2013). Gass defined ‘transfer’

as “the psychological process whereby prior learning is carried over into a new learning

19

situation” (p. 83). Transfer from learners’ first language can facilitate or hinder their second

language learning.

The Hierarchy of Difficulty suggested by Stockwell, Bowen, & Martin (1965) clearly

explains how differences between the first language and the second language impact transfer.

They categorized the differences between the first and the second languages into five groups:

differentiation, new category, absent category, coalescing, and correspondence. Differentiation

is regarded as a factor which makes language learning the most difficult and Correspondence

language learning the easiest. Gass (2013) presented the following table for the Hierarchy of

Difficulty by adapting Stockwell et al.’s (1965) theory.

Table 3

Hierarchy of Difficulty

CATEGORY

EXAMPLE

Differentiation

English L1, Italian L2: to know versus sapere/conosceres

New category

Japanese L1, English L2: article system

Absent category

English L1, Japanese L2: article system

Coalescing

Italian L1, English L2: the verb to know

Correspondence

English L1, Italian L2: plurality

(Gass, 2013, p. 90)

Table 3 shows that articles are a difficult area for Japanese learners because they do not

have articles in their native language. For Japanese, English articles are a ‘new category’ that

challenges their language development. In the same way, many language learners such as

Korean, Chinese, or Russian who lack articles in their native languages show that they have

difficulty with acquisition of English articles (Schönenberger, 2014; Ionin et al., 2004).

20

While behaviorism strongly supports the influence of native language on SLA, results

from some studies on child language acquisition throw doubts on the behavioristic view of native

language. Based on investigation on morpheme order of children’s first language acquisition, a

number of researchers have proposed that second language acquisition is similar to a child’s

native language learning.

Dulay and Burt (1974) examined two different groups of children, 60 Spanish children

and 55 Chinese children. Using Bilingual Syntax Measure (BSM), which was devised to elicit

English morphemes from participants, they found that these two groups of children, who are

from different native language background, have similar developmental acquisition patterns of

English morphemes: Pronoun case, Article (a, the), Progressive (-ing), Contractible copula (‘s),

Past irregular, Long plural (-es), Possessive (‘s), and 3

rd

person (-s). With these results, they

suggested that universal language acquisition patterns exist, and that the role of learners’ first

language is less significant in SLA (Dulay & Burt, 1974).

The universal pattern in acquisition of English morphemes was also found in a study on

adult language learners by Bailey, Madden, and Krashen (1974). They performed research on ‘a

natural sequence’ of morphemes acquisition, using the same BSM method in Dulay and Burt’s

(1974) study, with 33 native Spanish speakers and 40 native speakers of different languages.

They proposed that there was a ‘natural sequence’ in adult language acquisition regardless of

their native languages (Bailey et al., 1974).

On the other hand, even though above studies on English morpheme order diminished the

influence of native language on SLA, the role of first language is still supported by a number of

other studies. Luk and Shirai (2009) conducted morpheme studies with a variety of different

21

language groups comprised of native speakers of Korean, Japanese, Chinese, and Spanish. In

their research, only Spanish group turned out to follow the ‘natural order’ of morpheme

acquisition while other groups acquired plural-s, articles, and possessive‘s in a different order,

than the predicted natural sequence. This suggests that the learners’ native language may

influence SLA.

Research on ESL Students’ English

Article Use

Since the misuse of articles is one of the most common mistakes that language learners

make when attempting to learn English, there has been much research performed on L-2 learners

whose native language have no articles.

Yamada and Matsuura (1982) investigated article use by Japanese students using cloze-

type tasks, and found that the difficulty varied by which type of article was used. In their study,

both advanced and intermediate group performed well on using definite article the. Even though

the intermediate group showed difficulty with appropriate use of zero article, they improved as

they advanced. However, they did not show the same improvement when using indefinite

articles. Even advanced learners had difficulty using indefinite articles. Yamada and Matsuura’s

(1982) study makes it clear that language teachers should be aware that language learners may

have more difficulty using certain articles.

Zdorenko and Paradis (2008) performed a longitudinal study of 2 years on article

acquisition by children learning a second language. They studied two different groups: one

whose native languages do not have articles (Korean, Japanese, and Chinese) and the other

whose native languages do have articles (Arabic, Spanish, and Romanian). They used picture

books to elicit children’s speech and examined their discourse. In their research, they found that

22

participants, apart from their native language, used the instead of a/an in ‘indefinite specific

contexts’ and are better at using the in definite contexts than using a/an in indefinite contexts.

Subjects without articles in their native languages made more errors, including omitting articles,

but primarily at the beginning stages of language development. With these results, Zdorenko and

Paradis (2008) argued that the influence of native language on second language acquisition is not

significant.

Ko, Ionin, and Wexler (2009) examined how English articles are acquired by ESL

learners whose native language does not have an article system. Their study was focused on

learners’ perception of definiteness, specificity and partitivity regarding article use. They used a

written elicitation activity with Korean adult students whose native language does not have

articles. In their study, learners related the definite article the to both specific and partitive

meaning, and showed tendency to over-employ the for “specific indefinites and partitive

indefinites” (p. 23). According to Ko et al. (2009), there is a pattern in learners’ errors with

English articles, which could be explained in terms of Universal Grammar.

Haiyan and Lianrui (2010) performed a pseudo-longitudinal study on 121 Chinese

English learners to investigate students’ use of articles, using both qualitative and quantitative

research. The Chinese students were divided into three groups based on their English

competency; Lower-intermediate, Intermediate, and Advanced. In the study, all three groups

showed an accuracy order in English article use: the → a/an → Ø (zero article). Ø was the most

difficult article for them to master. They argued that learners tend to master the before a/an, and

then acquire Ø. They also found that Ø was overused by the advanced group but underused by

23

the lower-intermediate and intermediate groups; the lower-intermediate and intermediate groups

showed a tendency of overusing the and a/an.

Schönenberger (2014) examined English article use by Russian and German students.

Article choice in the German language depends on definiteness which is the same method used

in English, while in Russian, the word order, morphology and aspect denote definiteness

(Schönenberger, 2014). The results of the study demonstrate that the German group did not have

much difficulty in choosing a correct article whereas Russian groups made a lot of mistakes

when choosing the correct English article. Russian students’ accuracy correlated to their level of

English learning. One Russian group that had studied English for a long time showed a clear

tendency to fluctuate between specificity and definiteness whereas the other Russian group,

which had less English knowledge, showed irregular mistakes in English article use. Even

though two Russian groups showed different results, Schönenberger’s (2014) study suggests that

the correct usage of each article is dependent on the students’ native language’s similarity to

English.

Park (2013) studied the acquisition of English articles with 77 Korean English learners as

an experimental group and 21 native English speakers as control group to prove the Interface

Hypothesis in Korean speakers’ acquisition of English. According to Park, in Interface

Hypothesis, it is proposed that “different interfaces pose different levels of difficulties in learning

second language properties” (p. 155). Park related generic use of articles to ‘internal interface’

which is associated with semantics, and (in)definiteness to ‘external interface’ which is

connected to discourse. In her study, Korean students showed higher scores in using articles for

generic meaning compared to articles for (in)definiteness, supporting Interface Hypothesis.

24

Chapter 3: Methodology

Research Questions

The research that will be presented in my thesis is designed to obtain a general idea of

article use by Korean English speakers, and thereby help EFL/ESL teachers better understand

their Korean English students. For this purpose, I addressed the following questions through this

research.

1. Among the definite, indefinite, and zero article, is there an accuracy order that can be

shown in learners’ use of English articles? In Yamada and Matsuura’s (1982) study,

Japanese English learners showed decreasing accuracy in the order of the → a/an →

Ø (from the easiest to the most difficult) in their article usage. Haiyan and Lianrui

(2010) also found the same pattern of the → a/an → Ø (from the easiest to the most

difficult) in English article usage of Chinese English speakers. Do Korean English

learners show a similar tendency in their article use?

2. How does exposure to English speaking surroundings influence English article

acquisition by Korean students? (Participants are grouped based on the length of

their stay in English speaking countries.)

3. Between definite contexts and indefinite contexts, in which contexts do Koreans show

higher accuracy in using articles? In other words, is there any difference of accuracy

in article use between definite contexts and indefinite contexts?

4. What type of errors do Koreans make between a/an and zero article in definite

contexts where the is required and also between the and zero article in indefinite

contexts where a/an is required?

25

Participants

Thirty-five Korean students studying at a public university in the upper Midwest area

participated in the research. These students were born and raised in Korea and then came to

America later to study. I chose Korean university students regardless of age or major, who were

native speakers but used English as their second language, as participants. These students are

from different majors including engineering, education, economics, English, etc., and their ages

range between 19 and 37.

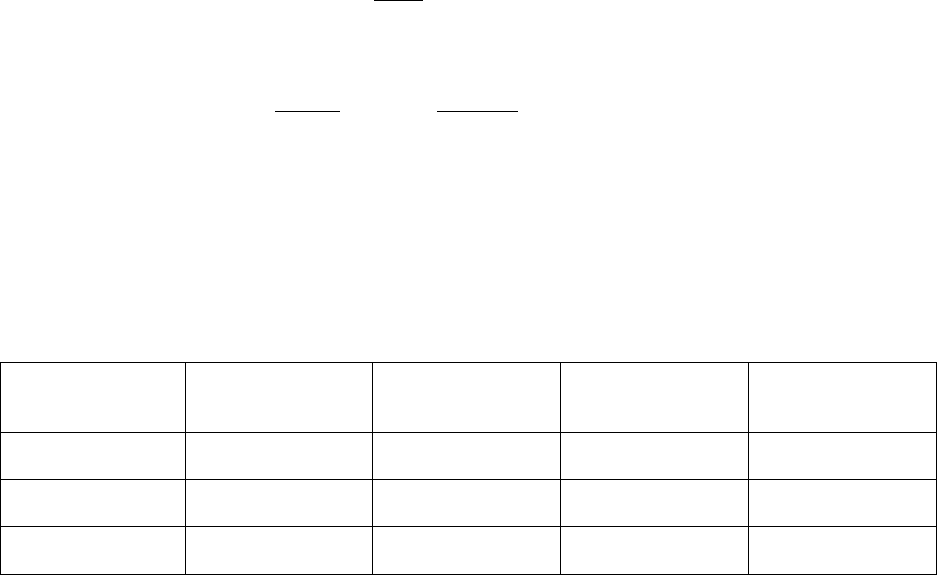

Table 4

Characteristics of Participants

35 Korean Students Learning English as a Second Language

Number

35 (25 female; 10 male)

Education Level

9 graduate; 26 undergraduate (currently)

Age Range

19-37 (Mean: 23.91; Median: 22; SD: 5.11)

Time Spent in English Speaking Countries

4-84 months (Mean: 28.46; Median: 24; SD: 22.36)

Because of the limitation that the participant must be a Korean studying at a university

level and the fact that there are limited numbers of Korean students around the area, finding an

ideal sample group with equal number of male and female or graduate and undergraduate

students was challenging. Thirty-five students in total, 25 females and 10 males, volunteered to

participate in this study. It is a mixed group with nine graduate students and 26 undergraduate

students. Time spent in English speaking countries, mostly America, was recorded. A couple of

freshman students replied that they have spent 4 months in the United States, which was the least

26

exposure in an English-speaking country, while the longest recorded exposure in America was

84 months.

To find the relationship between accuracy of article use and length of stay in English

speaking countries, participants were divided into three groups based on the length of their stay

in an English-speaking country. The first group were students who had lived in an English-

speaking country for less than a year. The students whose length of stay in an English-speaking

country was more than a year but less than 3 years comprised the second group. The third group

of students had lived in an English-speaking country for more than 3 years.

Korean students usually learn English as a foreign language from elementary school or

middle school to high school. Students participating in this study have learned EFL in Korea for

6 to 10 years and lived in an English-speaking country for some period of time, from a few

months to up to almost 7 years. Participants’ English levels were not evaluated and their official

English test scores were not recorded either in the research questionnaire for this research.

Since they are regular students enrolled in college degree programs that are taught in

English, participants are expected to have sufficient English competency to be successful in

those classes. To enter a college program, either undergraduate or graduate at a university in

America, most international students are required to prove some degree of English competency.

English proficiency is usually measured by TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) and

IELTS (International English Language Testing System) scores.

According to admission guidelines of the university in which the participants in this study

are enrolled, a TOEFL score of 61 or higher or an IELTS score of 5.5 or higher indicates

proficiency for the entrance of an undergraduate program. Graduate students are typically held

27

to an even higher standard. Therefore, based on this information, it is assumed that the

participants have at least an intermediate level proficiency of English knowledge, which allows

them to live in the U.S. and participate in collegiate lectures.

Most Korean English learners study English as a foreign language and rarely have

exposure to English-speaking surroundings. When they try to learn English in English-speaking

countries they struggle to overcome fossilization of pronunciation and some structure rules that

are different from their native tongue. The subjects chosen for this project were expected to

represent general college level Korean English speakers, learning English as a second language.

Description of Data Collection Instruments

The method chosen to investigate the article use of Korean students is discourse analysis.

According to Gee (2011), “discourse analysis is the study of language-in-use” (p. 8). The focus

of discourse analysis is various depending on the purpose of the research. Some might only

observe the content of speech and others put focus on the grammar of language being used in

discourse (Gee, 2011). The discourse analysis which is designed for this study focuses on the

grammar, particularly the English articles.

An oral translation task involving voice recording was employed to elicit a student’s

ability to correctly use English articles in speech. A Korean folk tale, “Gold Ax and Silver Ax”

was used for this activity. The story “Gold Ax and Silver Ax” is a popular folk tale that many

Koreans grew up reading and hearing. Children in Korea may have heard a different version of

this story.

The researcher reconstructed a Korean version of this folk tale “금 도끼 은도끼” (Gold Ax

and Silver Ax) using a Korean version (Kim, 2003) and an English version of the story from a

28

blog post from the Center for English as a Second Language (CESL) (Rina, 2013). I combined

them and simplified them and made my own Korean version for this research study.

Using a simple story rather than only using pictures or interview questions is an effective

method to draw a discourse from the participants. In this way, speakers do not need to create the

content. Because there is a Korean version of the story which is required to be translated as

exactly as possible, they will be required to use English articles in the correct context. Contrary

to most article studies which use a written forced-choice elicitation task such as a cloze-type test

or fill-in-the blank test, this research used an oral-based test which requires participants to create

their own sentences, whereby their use of English articles can be judged.

Laufer and Eliasson (1993) found that Swedish learners of English seemed to avoid

certain language uses due to the differences between English and Swedish. When learners face a

language property of a second language that is foreign to their native language, they have

difficulty using it correctly and avoid the property altogether. This is one of the reasons that I

chose the oral translation task for my research method. The Korean version of the story does not

have any articles because the Korean language does not have articles, but the participants in my

research study will decide which articles to use when they translate the written form of the story

in Korean into English speech.

Along with the oral translation task, a questionnaire was used to gather general

background information about the participants. The questionnaire contained questions such as

age, sex, education level, length of stay in English-speaking countries, etc.

29

Procedures

For the research, each participant received a copy of “Gold Ax and Silver Ax” in Korean

and were asked to retell the story in English, translating Korean sentences into English sentences

orally. They were given a voice recorder to record their oral translation into English. Three

minutes were given to read through the story in Korean before they started their oral translation.

It was expected to take about 3-5 minutes for each participant to complete the oral translation

task.

Participants were gathered personally by I, the author, and by my acquaintances.

Because more than two-thirds of them were recruited by my acquaintances, most of them did not

have a personal relationship with the author. Oral translation and voice recording took place

primarily at the school library, school café, or student union center during the week days. After

finishing their oral translation, a majority of the participants reported that this activity was more

challenging than they expected and thought that they had made many grammatical mistakes.

Participants were intentionally not informed that the focus of the research was the use of

English articles to avoid participants’ conscious effort to use English articles correctly.

However, the participant and the researcher read out loud the IRB-approved debriefing statement

together after completion of the translation task, in which the participants were informed of the

purpose of the research and that they could withdraw from the research study at any time. Also,

they were instructed to leave their email if they wanted to receive the research results after

participation. After listening to the instruction from the researcher, each participant pressed the

start button on the recorder and started translating. To reduce the participants’ anxiety and self-

30

consciousness, the researcher stayed about 20 feet away and avoided verbal communication so

they could focus on the task of oral translation without distraction.

Participants’ oral translations were recorded, saved with identifying numbers, and

transcribed using Microsoft word for the analysis. The transcription of each participant was

analyzed using TLU methods to find the accuracy pattern of the article use in their speech.

Every article use and misuse by learners was calculated and processed through TLU formula.

ANOVA was used to calculate a relationship between accuracy of article use and length of stay

in an English-speaking country. In addition, use of each article was counted based on definite

and indefinite contexts to see in which context learners demonstrated more correct or incorrect

use of articles.

The length of voice recordings from this project varied depending on the speech speed of

each participant, ranging between 2 minutes 25 seconds and 7 minutes 37 seconds. The average

word count was 304 words. The shortest transcript had 259 words while the longest transcript

had 455 words with a median of 303 words.

Data Coding

Because the instrument story was shortened to fit into the research, there was no need to

reduce the participants’ discourse. The original story was reconstructed so that it could provide

contexts where all three target articles were needed to translate the story correctly in English.

However, the task was not a forced-elicitation test and the number of each article incident was

not controlled.

To find the accuracy order in definite, indefinite, and zero articles usage, two types of

scoring methods were considered for the analysis of the data. The first calculating method to

31

count accurate use of grammar was Suppliance in Obligatory Context (SOC), which was

introduced by Brown (1973). With this method, the numbers of obligatory contexts in which

learners must provide target forms are counted along with whether learners used the target forms

correctly or not. The formula is as follows.

SOC=

number of correct suppliance x 2+number of misformations

total obligatory contexts x 2

(Gass, 2013, p. 69)

Even though the SOC method provides scholars with a fine scoring technique to calculate

learners’ correct output, Goldschneider and DeKeyser (2001) insisted that SOC can be

problematic in two aspects: focusing on accurate use of morphemes can make researchers

overlook the “structure of the inter-language” it also fails to notice the “overgeneralization and

overuse” of morphemes.

Pica (1983) introduced a different statistical method which is known as Target-Like Use

(TLU), in which the problems argued by Goldschneider and DeKeyser (2001) were corrected by

calculating the number of the suppliance in obligatory contexts as well as in non-obligatory

contexts. The following is the formula for the Target-Like Use.

TLU = =

number of correct suppliance in obligatory contexts

(

n obligatory contexts

)

+ (n suppliance in non−obligatory contexts)

(Gass, 2013, p. 70)

I chose to use Target-Like Use (TLU) analysis for this research since it addresses the

characteristics of inter-language and it provides information regarding language use in

inappropriate contexts. Part of the analysis plan for this research requires counting learners’

article use in [+] article contexts as well as [-] article contexts. Therefore, TLU is the most

appropriate for the purpose of this study.

32

Coding for TLU

To calculate TLU for each article provided by participants, all the articles in each

transcript were counted based on obligatory and non-obligatory context. TLU calculation

requires three numbers:

1. Number of correct ‘A’ Suppliance in Obligatory Context;

2. Number of obligatory contexts which require ‘A’ suppliance;

3. Number of ‘A’ suppliance in non-obligatory contexts.

The following sentences extracted from subject number 1’s speech show examples of

each article that are correctly used in obligatory contexts or overused in non-obligatory contexts.

Counting zero articles can be controversial. Subjects might use a zero article correctly, as

in front of plural nouns. Subjects might also omit an article by mistake or avoid using an article

because (s)he is not sure. For this study, those different possibilities were not considered and

zero articles were simply counted based on obligatory and non-obligatory contexts.

“Once upon a time, there is a mountain spirit lives in the pond.”

(__time) a correct use in obligatory context

(__mountain) a correct use in obligatory context

(__pond) the incorrect use in non-obligatory context

“One night, Ø wooden man came to a pond, cut a tree with Ø iron ax.”

(__wooden man) Ø incorrect use in non-obligatory context

(__pond) a incorrect use in non-obligatory context

(__tree) a correct use in obligatory context

(__iron ax) Ø incorrect use in non-obligatory context

33

“He dropped his iron ax in the pond.”

(__pond) the correct use in obligatory context

“He doesn’t have Ø money to buy Ø new one.”

(__money) Ø correct use in obligatory context

(__new one) Ø incorrect use in non-obligatory context

Table 5

Subject #1 TLU Scores

Article

n obligatory

context

n suppliance in

non-obligatory

context

n correct suppliance

in obligatory

contexts

TLU

the

30

1

16

0.52

a/an

11

4

5

0.33

Ø

3

18

3

0.14

Table 5 shows how subject number 1’s TLU scores were calculated for the, a/an, and

zero article. Subject 1 produced 30 contexts in her sentences that required the definite article

the. She provided 16 the correct and one incorrect by overusing it in a non-obligatory context.

In her speech, there were 11 contexts that needed a/an article. She got five correct and four

incorrect with a/an. For the contexts where zero article was required, she provided three correct

usages and 18 incorrect by missing an article where the or a/an articles were required. As a

result, she got her TLU scores as follows: 0.52 for the, 0.33 for a/an and 0.14 for zero article.

Coding for Article Use in Definite and

Indefinite Contexts

To measure the accuracy of article use between definite and indefinite contexts and

analyze the error types of article use in definite and indefinite contexts, the number of articles

that subjects provided for the task were counted based on definite and indefinite contexts. The

34

following sentences extracted from some of the subjects’ speech show examples of how they

used the, a/an, zero article in definite and indefinite contexts. For this study, articles used only

in front of common nouns that require an article were counted. Article the was expected to be

used when a noun had been mentioned previously in the discourse and is considered definite,

while the articles a/an were expected when a new noun was introduced in the discourse, which is

considered indefinite.

Subject #17

“A long time ago, Ø mountain spirit lived in Ø pond.”

(Ø mountain) Ø in indefinite context

(Ø pond) Ø in indefinite context

Subject #34

“A farmer heard the story.”

(A farmer) a in indefinite context

(the story) the in definite context

Subject #5

“So the farmer went back to the pond and purposefully he put the iron ax in the

pond.”

(the farmer) the in definite context

(the pond) the in definite context

(the iron ax ) the in indefinite context

(the pond ) the in definite context

35

Subject #18

“However, so Ø mountain god appeared in front of Ø farmer and asked him…”

(Ø mountain god ) Ø in definite context

(Ø farmer ) Ø in definite context

Subject # 21

“As a mountain spirit was going back to the pond that ….and brought up to the

gold ax….”

(a mountain spirit) a in definite context

(the pond) the in definite context

(the gold ax) the in indefinite context

36

Chapter 4: Results and Discussions

Data gathered through this research were analyzed in three ways. First, transcripts of the

voice recordings were analyzed to examine the differences of data and their effects on the results.

Second, TLU scores for three different articles were calculated and analyzed to discover an

accuracy order and the relationship between the length of stay in English speaking countries and

correct article use. Finally, article use in each definite and indefinite context was examined to

discover a pattern regarding correct or incorrect article use in each definite or indefinite context.

Different Transcripts in Various Lengths

It is noteworthy to see how participants translated the same story from Korean into

English in different ways and with various lengths. The average word count was 304 words.

The shortest transcript had 259 words and the longest transcript had 455 words with a median of

303 words. In order to examine the relationship between the length of participants’ speech and

TLU scores, the scripts of participants numbered 6, 25, and 21 were analyzed. Script 6 showed

the median length of script with 303 words, script 25 was the shortest with 259 words, and script

21 was the longest with 455 words.

The elicitation tool that I chose was not designed to force participants to speak a certain

number of articles or choose specific articles. It only required participants to translate a Korean

story into English. Some participants chose longer sentences, producing many words, but some

chose shorter sentences with less number of words. As shown in following three transcripts,

even the first sentence is different in each transcript.

37

#6 A long time ago, mountain spirit lived in pond.

#25 Long time ago, mountain spirit lived in the pond.

#21 Long long time ago, the mountain spirit was living in the pond.

Calculating TLU scores requires the number of obligatory contexts where the target

article is required, the occurrence of the target article in obligatory contexts, and the number of

the target article in non-obligatory contexts. To discover how different numbers of words from

participants can impact TLU scores, three subjects’ speech of various length (median, shortest,

and longest length) were analyzed in Table 6.

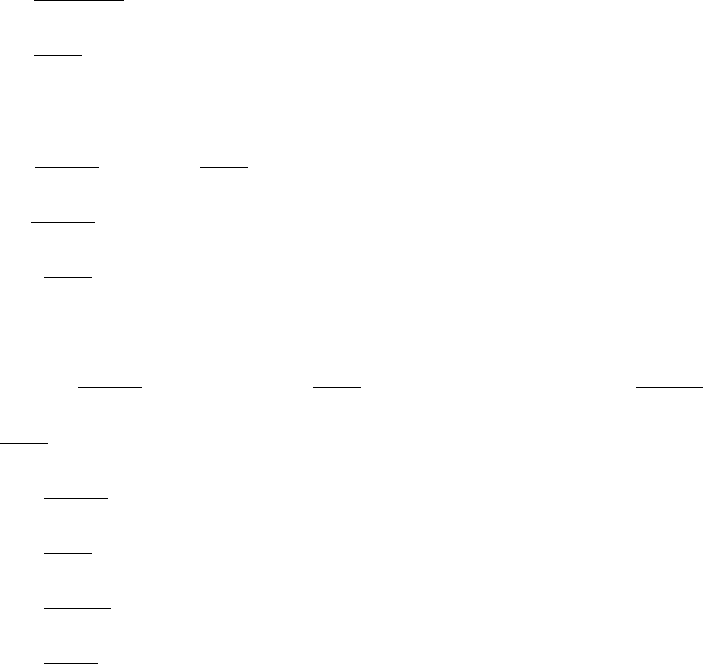

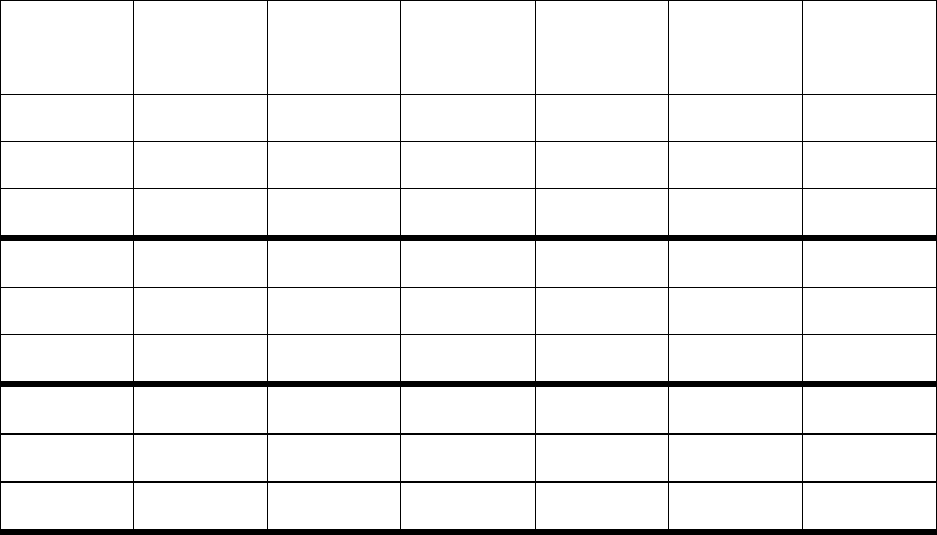

Table 6

Word Counts and TLU Scores for Three Selected Subjects

Subject

Word Count

Article

n Obligatory

Context

n Suppliance

in non-

obligatory

context

n correct

suppliance in

obligatory

contexts

TLU

THE

34

1

29

0.83

6

303

A/AN

10

1

3

0.27

ZERO

3

9

3

0.25

THE

32

3

21

0.60

25

259

A/AN

15

0

3

0.20

ZERO

0

20

0

0.00

THE

41

10

30

0.59

21

455

A/AN

11

3

0

0.00

ZERO

1

10

0

0.00

As shown in Table 6, a higher number of words in a participant’s speech did not

necessarily positively correlate with TLU scores. Subject 21 spoke the most words among all the

38

subjects. She produced 41 nouns that required the article the and correctly said the in 30

obligatory contexts but 10 times in non-obligatory contexts, getting her TLU score for the with

0.59. On the other hand, subject 25 used the least number of words and created only 32 contexts

that required the. She provided the in 21 obligatory contexts and only three in non-obligatory

contexts. As a result, her TLU score for the was higher than subject 21 who spoke the most

words. Although subject 21 created a lot of contexts for the article the, she also made many

mistakes with the by misusing it, which occurred 10 times, the highest number of mistakes with

the article the among the three.

TLU Scores, Order of Accuracy, and

Length of Stay in English

Speaking Countries

To calculate an order of accuracy for participants’ article use of the, a/an, and Ø, the

means and TLU scores were calculated and compared for each English proficiency group and for

all the students collectively. In Table 7, Group A represents the students who have stayed in an

English-speaking country for less than a year. Students who have lived in an English-speaking

country for more than 1 year but less than 3 years comprised Group B. Group C students have

resided in an English-speaking country for more than 3 years.

39

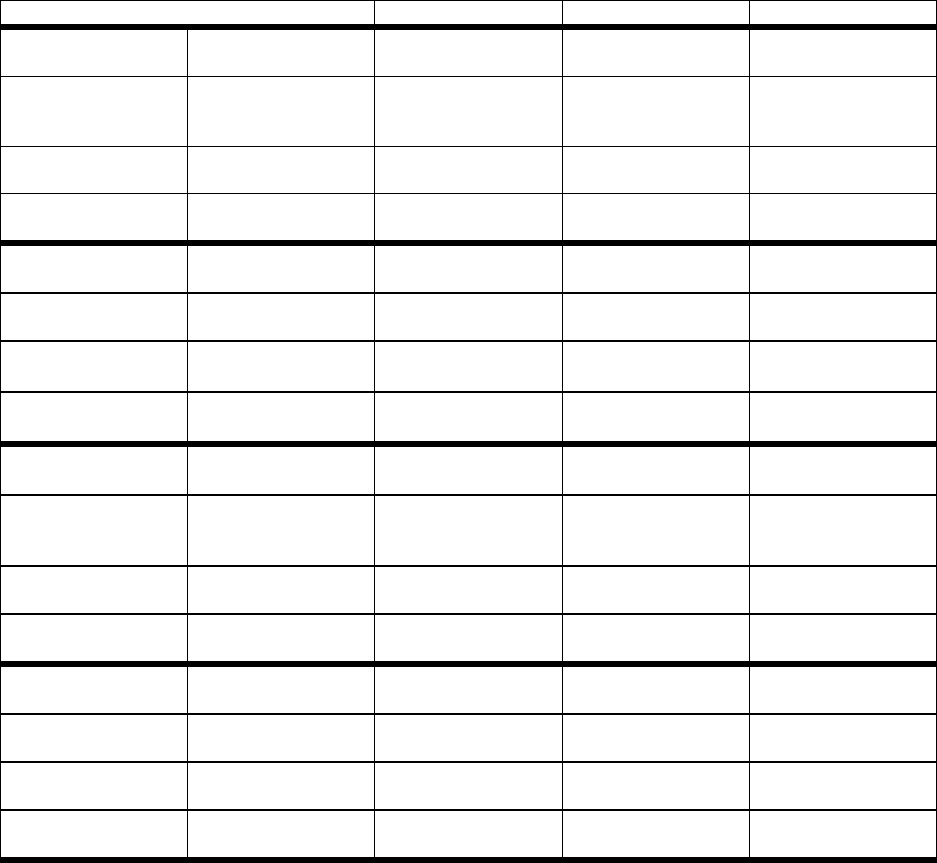

Table 7

TLU Scores of Three Groups

GROUP

THE

A/AN

ZERO

A

Mean

0.61

0.37

0.10

(residence less than

1 year)

Median

0.58

0.34

0.07

Std. Deviation

0.20

0.22

0.11

N

12.00

12.00

12.00

B

Mean

0.70

0.37

0.24

(1-3 years)

Median

0.81

0.33

0.14

Std. Deviation

0.21

0.20

0.30

N

11.00

11.00

11.00

C

Mean

0.70

0.39

0.12

(more than 3 years

of residence)

Median

0.76

0.38

0.08

Std. Deviation

0.15

0.25

0.14

N

12

12

12

TOTAL

Mean

0.68

0.37

0.10

Median

0.72

0.33

0.09

Std. Deviation

0.19

0.22

0.22

N

35

35

35

The results show all three groups show a similar pattern in their article use. They all

demonstrated the highest TLU score with the article the. The average TLU score of all the

participants for the article the is 0.68. The article a/an got the second highest score from all three

40

groups, with the average TLU score of 0.37. All three groups had the lowest TLU score for the

zero article usage.

One of the purposes of this research was to see if there is an accuracy order that can be

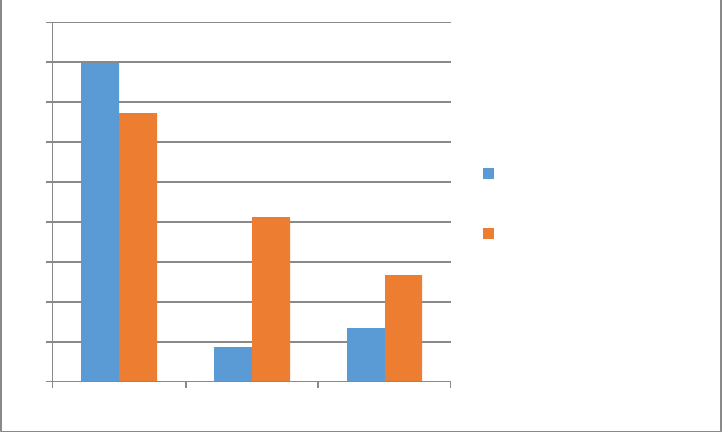

shown in Korean English learners’ English article use. Figure 1 illustrates that all three groups

scored the highest with the, second highest with a/an, and the lowest with zero article. This

suggests that Korean English learners have the most difficulty with using the zero article among

the three articles and the is the easiest article for Korean learners to learn compared to other

articles. Therefore, based on the results we conclude that Korean learners follow the accuracy

pattern of the → a/an → zero article in descending order of proficiency.

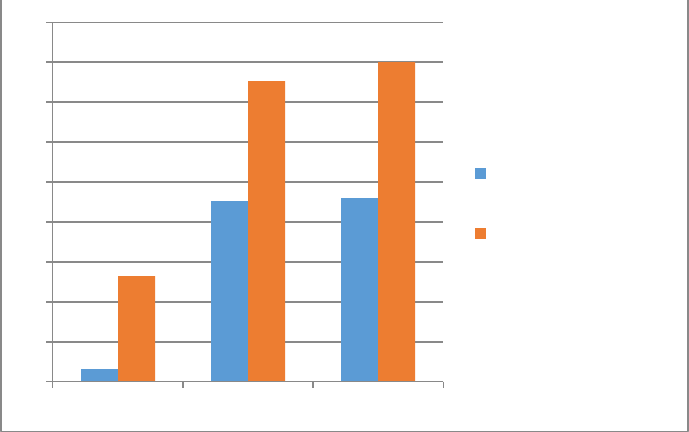

Figure 1

Three Groups’ TLU Scores for the, a/an, and zero article

This result coincides with an accuracy pattern that Haiyan and Lianrui (2010) found with

Chinese English learners. After conducting research on English article use for three groups of

learners with various English levels, they proposed that learners acquire the first, a/an next, and

zero article last. Earlier in Yamada and Matsuura’s (1982) study, Japanese English learners

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

0.80

the a/an zero

Group A

Group B

Group C

41

showed a similar pattern. According to Yamada (1982), their intermediate group followed the →

a/an → Ø and the advanced group showed the → Ø → a/an. The seems like the easiest among

the three articles for Korean, Chinese, and Japanese English learners. Chinese, Japanese, and

Korean have no article system as English does. Therefore, for English learners from China,

Japan, or Korea, English articles are a new category, which is high in the Hierarchy of Difficulty

which Gass (2013) proposed.

Next, the relationship between the length of residence in an English-speaking country and

TLU scores were examined to answer the second research question: How does exposure to

English speaking surroundings influence English article acquisition by Korean students?

Table 7 shows TLU scores for each group and the composite TLU scores for all

participants. When we compare the three groups’ TLU scores for each article usage, Group A’s

TLU scores for the and zero article are lower than the other two groups’ TLU scores for the

same articles. Otherwise, the results do not demonstrate significant TLU score differences

among my three research groups that have each resided in an English-speaking country of

various time.

Before rounding, Group B’s TLU score for the article the was 0.698448873522187,

which is higher than Group C’s TLU score for the 0.698178379610194. Group B’s TLU score

for zero article is higher by 0.12 compared to Group C’s. There is not a significant difference

between all three groups’ TLU scores.

42

Table 8

ANOVA Test Results

ANOVA

Sum of

Squares

df

Mean

Squares

F

Sig.

TLU

Between

Groups

0.68

2

0.034

0.93

0.405

(the)

Within

Groups

1.174

32

0.037

Total

1.243

34

TLU

Between

Groups

0.004

2

0.002

0.043

0.958

(a/an)

Within

Groups

1.608

32

0.05

Total

1.613

34

0.05

TLU

Between

Groups

0.124

2

0.062

1.581

0.221

(zero article)

Within

Groups

1.257

32

0.039

Total

1.382

34

To calculate a relationship between the length of stay in English-speaking countries and

TLU score for each article more precisely, a one-way ANOVA test was conducted. The results

with this sample group indicate that the length of stay in English-speaking countries does not

have a noteworthy effect on English article accuracy. As exposed in Table 8, analysis of these

three groups did not show any statistical significance of TLU scores for all three articles:

TLU(the), F=0.93, p=0.405; TLU(a/an), F=0.043, p=0.958; TLU(zero article), F=1.581,

p=0.221.

43

Schönenberger (2014) investigated Russian English learners, whose native language does

not have an article system, to examine how prior English study can affect Russian English

learners’ article use. There were 4 years of English study gap between two groups of learners

and their performance on an English article proficiency test did not show significant difference.

Although, the Korean participants for this research were grouped based on their exposure

in English-speaking countries rather than prior English study, staying in English speaking

countries for academic purpose is considered a very intense English-learning experience. The

English study time difference between the two Russian groups was 4 years. Schönenberger

(2014) insisted that knowledge of English articles rather than the length of English study had a

more important role on the students’ performance in her research.

Table 9

Average Stay in English Speaking Countries

Group A

N: 12

Less than 1 year

Average Stay: 8.83 months

Group B

N: 11

Between 1-3 years

Average Stay: 22.55 months

Group C

N: 12

More than 3 years

Average Stay: 53.5 months

As shown in Table 9, the average time differences among my research groups were about

14 months between Group A and B, 21 months between Group B and C, and 44.67 months

between Groups A and C. These time gaps might not be enough to make significant difference

on the subjects’ proficiency in article use. Also, the number of participants may not be sufficient

to make a reliable conclusion.

The results of this study do not provide significant evidence that the length of residence

in English speaking countries affects English article use. Further research is required about the

44

relationship between exposure to English speaking surroundings and English article use. Enough

time gaps spent in English speaking countries, the purpose of stay, or the age of the participants

during the residence in English speaking countries might need to be controlled for more rigorous

study.

Article Use in Definite and Indefinite

Contexts

To find out Korean English learners’ article use in definite and indefinite context, articles

were counted based on definite and indefinite contexts respectively. The following tables, Table

10 and Table 11, show the number of each article incidences counted from all 35 participants’

speeches. The numbers of articles were calculated in percentage for analysis.

Table 10

Article Use in Indefinite Context

Correct a

Incorrect the

Incorrect zero article

Total

Indefinite Context

(target a)

132

293

196

621

21.26%

47.18%

31.56%

100.00%

Table 11

Article Use in Definite Context

Incorrect a

Correct the

Incorrect zero article

Total

Definite Context

(target the)

95

571

163

829

11.46%

68.88%

19.66%

100.00%

There were 621 indefinite contexts from the speech of all participants where an indefinite

article a/an was required and 829 definite contexts in which subjects must put the definite article

45

the in front of a noun. Since I counted only common nouns that needed either an indefinite or

definite article in front of the nouns, all the zero articles counted in the above table are

considered as incorrect use.

As aligned with the accuracy order that we discussed in the previous page, the percentage

of correct use of the in definite contexts is higher than the percentage of correct use of a/an in

indefinite contexts. Correct the in definite contexts was 68.88% while correct a/an in indefinite

contexts was only 21.26%. Subjects show comparatively more accurate article use in definite

contexts than in indefinite contexts. To Korean English learners, it is more difficult to use

articles correctly in indefinite contexts compared to definite contexts.

The above results allow me to answer my third research question: Is there any difference

of accuracy in article use between definite contexts and indefinite contexts? The findings from

this study demonstrate that Korean English learners show higher accuracy with definite contexts

than with indefinite contexts in their English article use.

This is consistent with Zdorenko and Paradis’s (2008) study in which they investigated

two groups of children, one group whose native language had an article system and the other

group whose native language did not. They stated that both groups demonstrated more accurate

article use with definite context than with indefinite context (Zdorenko & Paradis, 2008). It is

suggested that English learners acquire the before other articles.

46

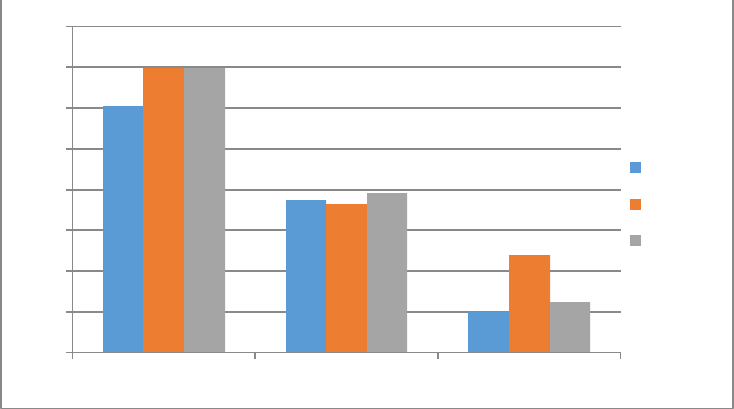

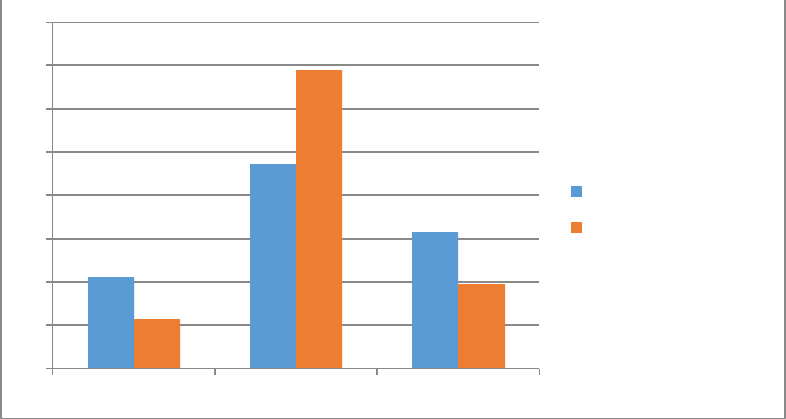

Figure 2

Correct Use of a/an in Indefinite Context and the in Definite Contexts

Figure 2 shows the three groups’ correct use of a/an in indefinite contexts and correct use

of the in definite contexts. All three groups utilized the more accurately. Group C students, who

have resided in an English-speaking country for more than 3 years, show high accuracy with

definite articles and score 80%. Group A students, who have stayed in an English-speaking

country less than one year, demonstrated poor proficiency with using a/an in indefinite contexts

with a score of only 3.09%.

Next, misuses of the or zero article in indefinite contexts and a/an or zero article in

definite contexts were analyzed to find out which article utilization mistake Korean learners are

more prone to make. The results show that in indefinite contexts, misuse of the is more common

than the misuse of zero article. In indefinite contexts, incorrect incidence of the was 47.18%

whereas the incorrect incidence of zero article was 31.56%.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Group A Group B Group C

correct a in indefinite

context (%)

correct the in definite

context (%)

47

Figure 3

Incorrect Use of the and zero article in Indefinite Contexts

Figure 3 presents all three groups’ article misuse of the and zero article in indefinite

contexts. The percentage of Group A’s incorrect use of the in indefinite contexts is 66.29%,

which is very high. Considering Group A’s correct use of the in definite contexts was only

26.57%, this group of students seem to fluctuate between the and a/an when they speak English.

Group B students utilized zero article incorrectly 42.86% of their opportunities, which was far

more than the percentage of the, at only 11.9% in indefinite contexts. However, the other groups

used the more than zero article. In general, misuse of the is more common than misuse of zero

article in indefinite contexts.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Group A Group B Group C

incorrect the in indefinite

context (%)

incorrect zero article in

indefinite context (%)

48

Figure 4

Incorrect Use of a/an and zero article in Definite Contexts

The three groups’ misuse of articles a/an and zero article in definite contexts were

analyzed in Figure 4. Group A demonstrated a high percentage of article misuse in definite

contexts with a/an (39.86%) and zero article (33.57%). Taking into consideration the percentage

of Group A’s use of the in definite contexts was only 26.57%, they used a/an or zero article

more than the in definite contexts. Except Group A, all other groups chose to use zero article

more than a/an in definite contexts, which means when they made an article mistake in definite

contexts, they omitted an article more frequently than they used a/an.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Group A Group B Group C

incorrect a/an in definite

context (%)

incorrect zero article in

definite context (%)

49

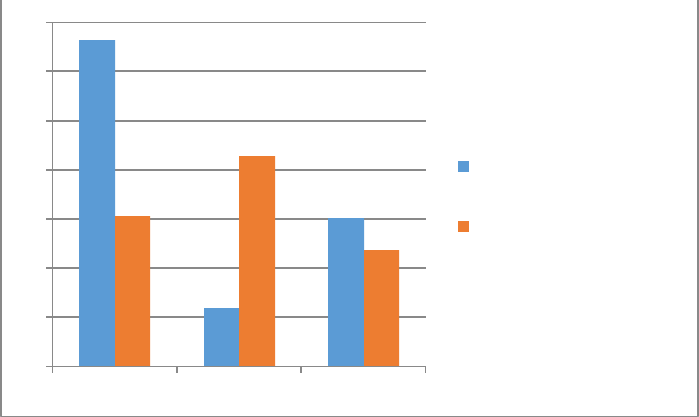

Figure 5

Each Article Use of Total Group in Indefinite and Definite Contexts

Figure 5 demonstrates the percentage of each article use from all 35 students’ speeches.

It is interesting that in indefinite contexts where a/an is necessary, participants chose incorrectly

to use the or zero article far more frequently than a/an. On the other hand, in definite contexts,

students used the significantly more than a/an or zero article showing high accuracy with using

the article the. A/an was the article that learners used the least in definite contexts. Therefore,

both in definite and indefinite contexts, participants used the the most and a/an the least.

The last research question asked what type of errors Koreans make between a/an and

zero article in definite contexts where the is required and between the and zero article in

indefinite contexts where a/an is required. As explained in the above discussions, participants

misused the more than zero article in indefinite contexts, while they misused zero article more

than a/an in definite contexts. In indefinite contexts, where a/an is required, students chose to

the, at 47.18%, far more than a/an at 21.26%. It seems that not only Korean English learners

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

a the zero article

Indefinite Context (%)

Definite Context (%)

50

show high accuracy with the when it is required but they also show high inaccuracy with the

when it is not required.

51

Chapter 5: Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

In order to investigate English article use by Korean English learners, an oral translation

assignment was given to 35 Korean students studying at a university in the upper Midwest of the

United States. Participants were expected to demonstrate their English article proficiency by

orally translating a short Korean story into English. Their translation was recorded, transcribed,

and analyzed for the research.

To discover if there is an accuracy order in Korean English learners’ article use among

the, a/an, and zero article, each article in the participants’ speech was counted and calculated

using TLU (Target-Like-Use). The results show a decreasing accuracy order with using the →

a/an → zero article (most proficient → least proficient) which aligns with Yamada and

Matsuura’s (1982) study involving Japanese English learners and Haiyan and Lianrui’s study

(2010) involving Chinese English learners. This suggests that Korean English learners master

the article the first while zero article is the most challenging to them.

I also intended to discover a causal relationship, if any, between the length of exposure to

English speaking surroundings and accuracy of English article use. It was not shown through this

research that the length of stay in an English-speaking country had positive effect on correct

English article use by Korean learners. The difference in the three groups’ accuracy for each