HOW DEFINITE ARE WE ABOUT THE ENGLISH ARTICLE SYSTEM? CHINESE

LEARNERS, L1 INTERFERENCE AND THE TEACHING OF ARTICLES IN

ENGLISH FOR ACADEMIC PURPOSES PROGRAMMES.

By

RICHARD NICKALLS

A thesis submitted to

The University of Birmingham

for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

Department of English Language and Applied

Linguistics

School of English, Drama and American &

Canadian Studies

College of Arts and Law

The University of Birmingham

December 2019

University of Birmingham Research Archive

e-theses repository

This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third

parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect

of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or

as modified by any successor legislation.

Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in

accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further

distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission

of the copyright holder.

ABSTRACT

Omission and overspecification of the/a/an/Ø are among the most frequently occurring

grammatical errors made in English academic writing by Chinese first language (L1) university

students (Chuang & Nesi, 2006; Lee & Chen, 2009). However, in the context of competing

demands in the English for academic purposes (EAP) syllabus and conflicting evidence about

the effectiveness of error correction, EAP tutors are often unsure about whether article use

should or could be a focus and whether such errors should be corrected or ignored. With the

aim of informing pedagogy, this study investigates: whether explicit teaching or correction

improves accuracy; which article uses present the most challenges for Chinese students; the

causes of error and whether a focus on article form can be integrated within a modern genre

based/student centred approach in EAP. First, a questionnaire survey investigates how EAP

teachers in higher education explicitly teach or correct English article use. Second, the effect

of explicit teaching and correction on English article accuracy is investigated in a longitudinal

experiment with a control group. Analysis of this study’s post-study measures raise questions

about the sustained benefits of written correction or decontextualised rule-based approaches.

Third, findings are presented from a corpus-based study which includes an inductive and

deductive analysis of the errors made by Chinese students. Finally, in a fourth study hypotheses

are tested using a multiple-choice test (n=455) and the main findings are presented: 1) that

general referential article accuracy is significantly affected by proficiency level, genre and

students’ familiarity with the topic; 2) Chinese students are most challenged by generic and

non-referential contexts of use which may be partly attributable to the lack of positive L1

transfer effects; 3) overspecification of definite articles is a frequent problem that sometimes

gives Chinese B2 level students’ writing an ‘informal tone’; and 4) higher nominal density of

pre-qualified noun phrases in academic writing is significantly associated with higher error

rates. Several practical recommendations are presented which integrate an occasional focus on

article form with whole text teaching, autonomous proofreading skills, register awareness, and

genre-based approaches to EAP pedagogy.

DEDICATION

This thesis is dedicated:

To my loving family, past and present.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

At the University of Birmingham, I am profoundly grateful to Professor Jeannette Littlemore

and Dr. Nicholas Groom for helping me through my Masters and then later supervising me at

Doctoral level. My thesis (perhaps even more so than most) has ended up a long way from

where we started (the proposal they agreed to supervise) and I’m very grateful for their

tolerance and continued interest. I need to express my sincere gratitude to the many students

who have participated in various studies and my many colleagues who have contributed to this

research.

There’s too little space to mention every single academic, student and colleague who has

generously helped me or simply exchanged ideas on this rather dry topic – but they know who

they are. A special thanks to Jane Sjoberg and my nephew Oliver for checking my thesis for

typos and inconsistencies. Thanks to Dr. Oliver Mason for use of his Java-based programme

to extract noun phrases and to Dr. Laurence Anthony of Waseda University for programming

(and regularly updating) the freely available Ant. Conc. Programme. For help in understanding

aspects of the Chinese language I must finally thank Zhijun Wang, Shimeng Liu and Xinyu Li.

i

Table of Contents

1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Brief overview ........................................................................................................ 1

1.2 Personal interest ...................................................................................................... 2

1.3 Background and justification for the research .......................................................... 4

1.4 Previous Research into Chinese L1 learners’ English article accuracy ..................... 8

1.5 Summary of research aims .................................................................................... 10

1.6 Thesis overview .................................................................................................... 11

2 LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................ 15

2.1 Key term definitions.............................................................................................. 15

2.2 The English article system .................................................................................... 17

2.3 Contrastive Analysis ............................................................................................. 26

2.4 Empirical research into Chinese L1 learners’ written L2 English errors ................. 32

2.5 Other factors influencing English Accuracy .......................................................... 41

2.6 English articles within the current EAP pedagogical paradigms............................. 49

2.7 Empirical research into the effect of teaching and correcting articles ..................... 52

2.8 Research Questions ............................................................................................... 55

ii

iii

3 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................... 59

3.1 Critical methodological issues in Error Analysis ................................................... 59

3.2 Error detection ...................................................................................................... 62

3.3 Error classification ................................................................................................ 65

3.4 Error explanation .................................................................................................. 66

3.5 Evaluation of recent methods in English article studies ......................................... 67

3.6 The need for a preliminary study ........................................................................... 75

3.7 Preliminary study .................................................................................................. 76

3.8 Summary of methodological approaches in main studies ....................................... 84

3.9 Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 85

4 SURVEY OF TEACHER ATTTITUDES AND PRACTICES .................................... 87

4.1 Background and recap of Research Question 1 ...................................................... 88

4.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 91

4.3 Results and Discussion .......................................................................................... 96

4.4 Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 122

iv

v

5 LONGITUDINAL STUDY OF THE EFFECT OF TEACHING/ CORRECTION ON 24

(L1 MANDARIN) LEARNERS OF ENGLISH ON A 15-WEEK PRESESSIONAL ENGLISH

COURSE .......................................................................................................................... 127

5.1 Study overview ................................................................................................... 128

5.2 Methodology ....................................................................................................... 129

5.3 Ethical issues ...................................................................................................... 143

5.4 Constraints of the study ....................................................................................... 145

5.5 Data analysis ....................................................................................................... 145

5.6 Tagging reliability checks and inter-rater reliability checks ................................. 151

5.7 Results and discussion......................................................................................... 154

5.8 Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 172

6 CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF CORPORA .......................................................... 177

6.1 Study overview ................................................................................................... 177

6.2 Methodology ....................................................................................................... 179

6.3 Data analysis ....................................................................................................... 184

6.4 Results and discussion......................................................................................... 186

6.5 L1 transfer effects ............................................................................................... 211

vi

vii

6.6 Linguistic context of noun phrases ...................................................................... 212

6.7 Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 215

7 TESTING OF HYPOTHESES USING ONLINE MULTIPLE-CHOICE

GRAMMATICALITY JUDGEMENT TEST .................................................................... 221

7.1 Study overview ................................................................................................... 223

7.2 Methodology ....................................................................................................... 225

7.3 Findings and discussion ...................................................................................... 235

7.4 Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 242

8 CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................................... 247

8.1 Restatement of aims ............................................................................................ 247

8.2 Summary of main findings .................................................................................. 247

8.3 Limitations and future research ........................................................................... 258

8.4 Recommendations for EAP instructors ................................................................ 259

8.5 Final comments ................................................................................................... 262

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 267

APPENDICES .................................................................................................................. 279

APPENDIX 1 ................................................................................................................ 279

viii

ix

APPENDIX 2 ................................................................................................................ 281

APPENDIX 3 ................................................................................................................ 293

APPENDIX 4 ................................................................................................................ 303

APPENDIX 5 ................................................................................................................ 311

APPENDIX 6 ................................................................................................................ 318

APPENDIX 7 ................................................................................................................ 322

APPENDIX 8 ................................................................................................................ 324

APPENDIX 9 ................................................................................................................ 334

APPENDIX 10 .............................................................................................................. 341

x

xi

Abbreviations

In this thesis, the following abbreviations are used:

BALEAP

BIA

CEFR

DELTA

EAP

EFL

EGAP

EISU

ELAL

ESOL

ESP

IELTS

L1

L2

OED

SELT

UKVI

British Association of Lecturers of English for Academic Purposes

Birmingham International Academy

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages

Diploma in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages

English for Academic Purposes

English as a Foreign Language

English for General Academic Purposes

English for International Students Unit (Former name of BIA)

Department of English Language and Applied Linguistics

English for Speakers of Other Languages

English for Specific Purposes

International English Language Testing System

First Language (once called ‘native language’)

Second Language

Oxford English Dictionary

Secure English Language Test

UK Visas and Immigration

xii

xiii

Table of Figures

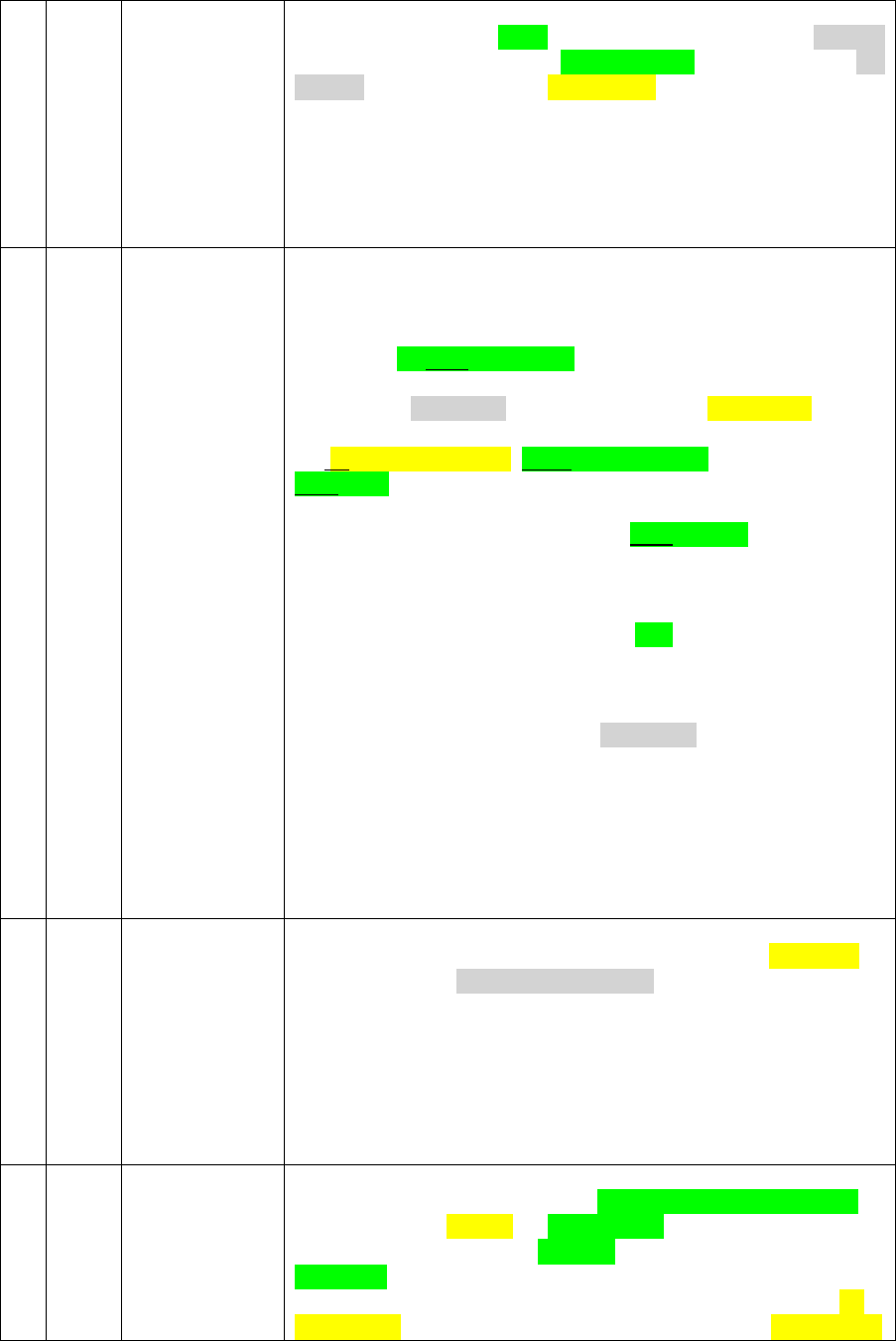

Figure 1: Examples of generic NPs in all forms (Krifka & Gerstner, 1987).......................... 20

Figure 2: Further examples of non-referential noun phrases from Ekiert (2004)................... 22

Figure 3: Comparison of means of missed the by category (Liu and Gleason, 2002: 13) ...... 33

Figure 4: Example of definite article ‘overuse’ from Lee & Chen (2009: 287) ..................... 35

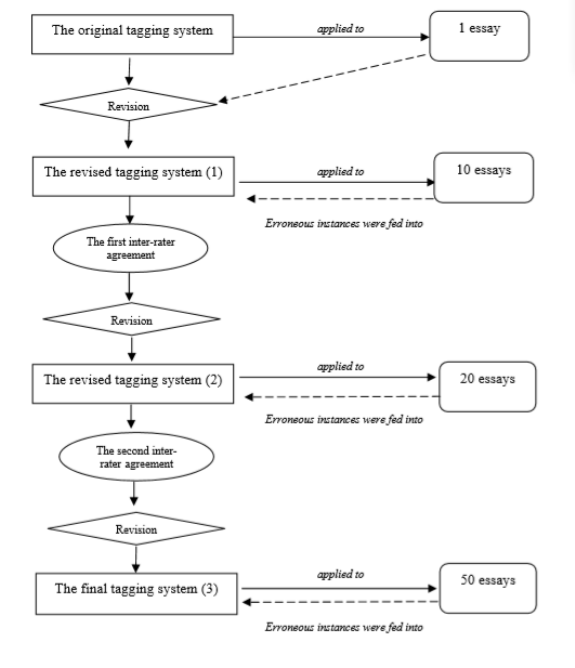

Figure 5: Reproduced from Chuang and Nesi (2006: 257): 3 stages of developing a tagging

system ................................................................................................................................. 75

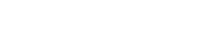

Figure 6: Summary of mixed method approach to Error Analysis ........................................ 85

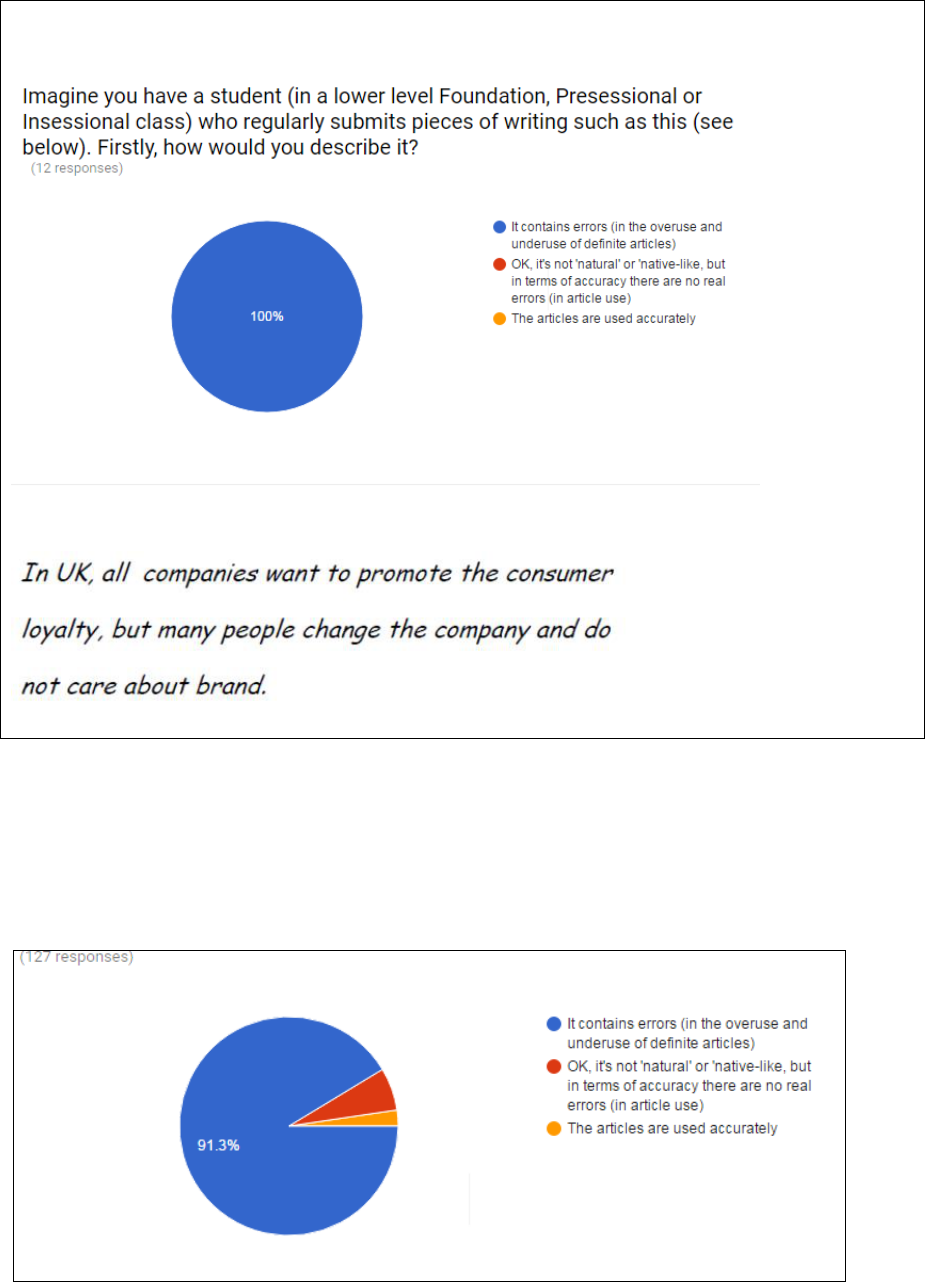

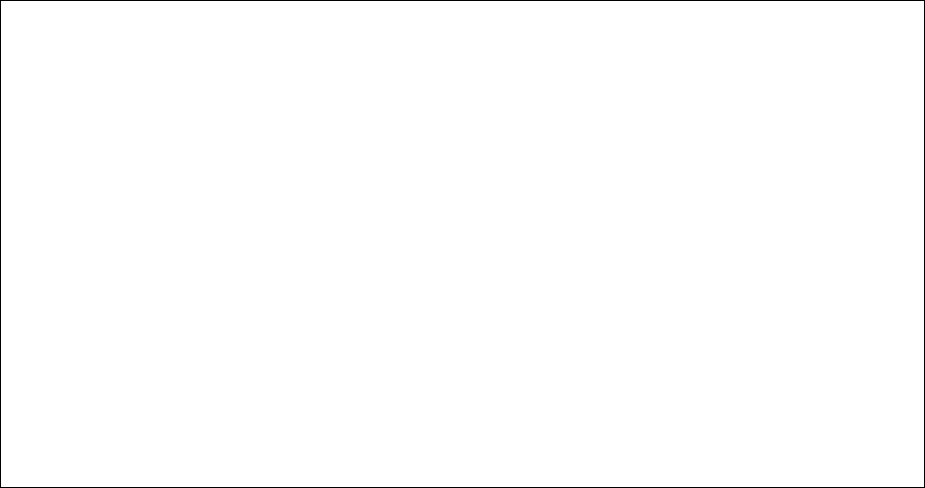

Figure 7: Survey Question 1 ................................................................................................ 93

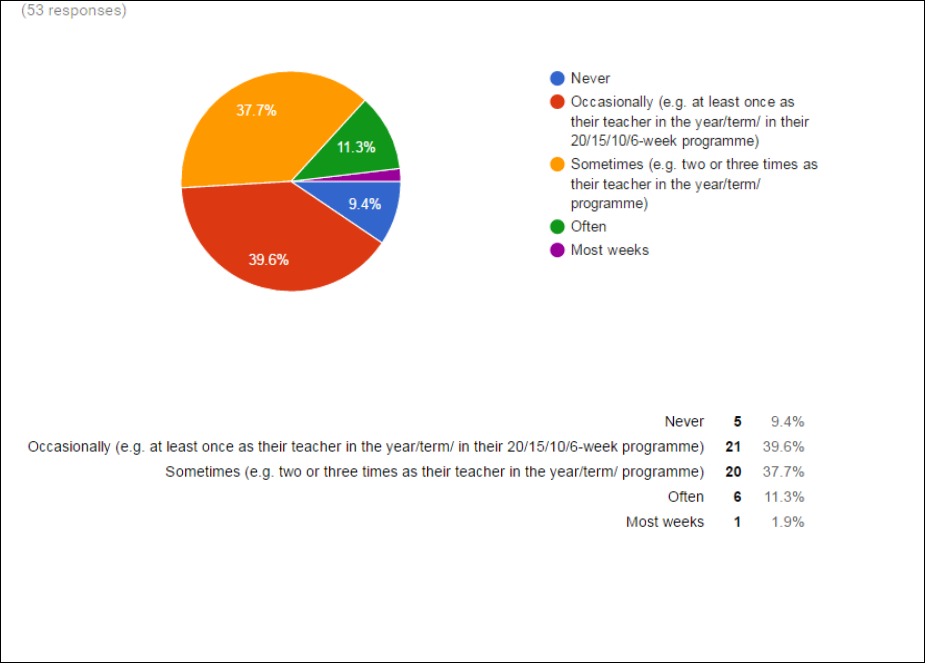

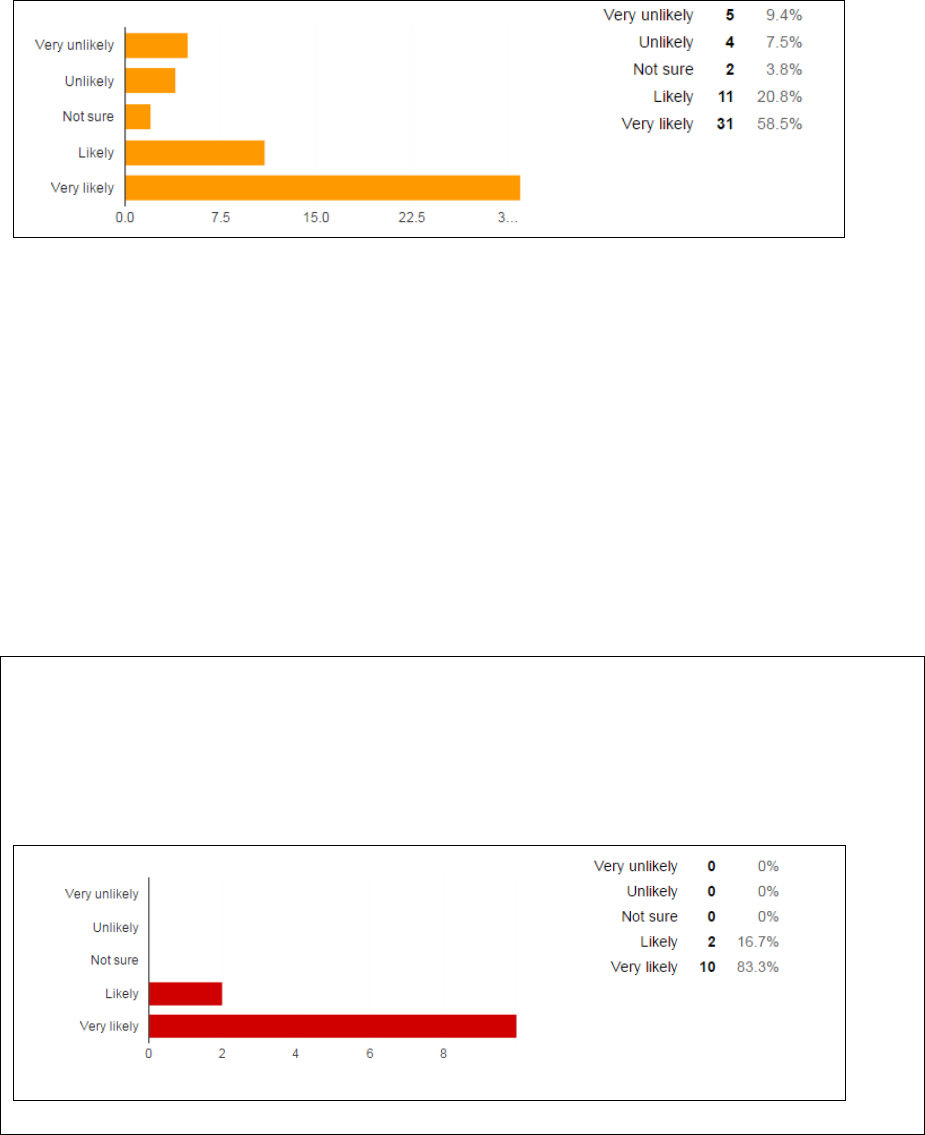

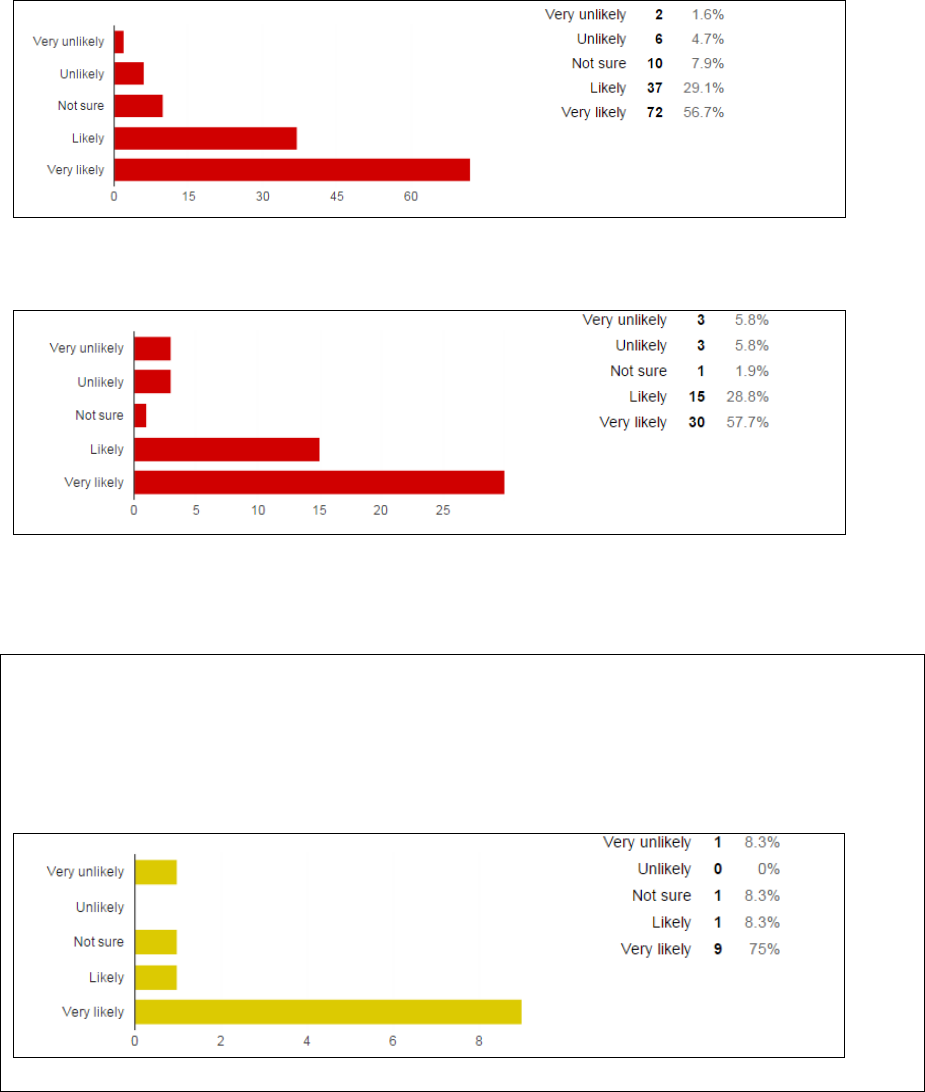

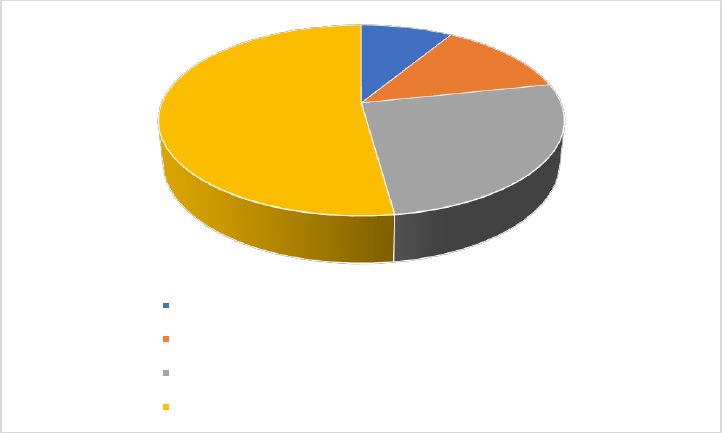

Figure 8: EISU EAP Tutor Responses to Question 1 (n=12) ................................................ 97

Figure 9: BALEAP mailing list responses to Question 1 (n=127) ........................................ 97

Figure 10: ELAL MA Distance programme responses to Question 1 (n=53) ....................... 98

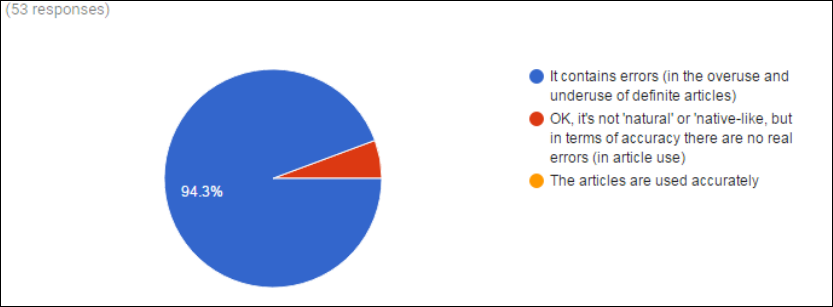

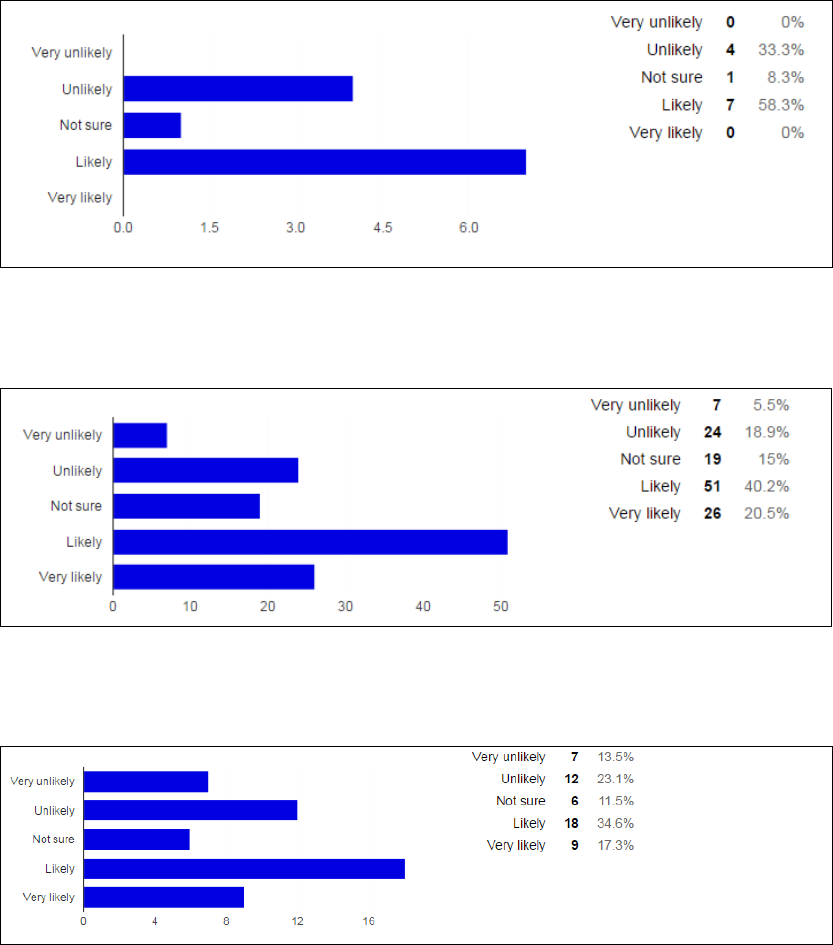

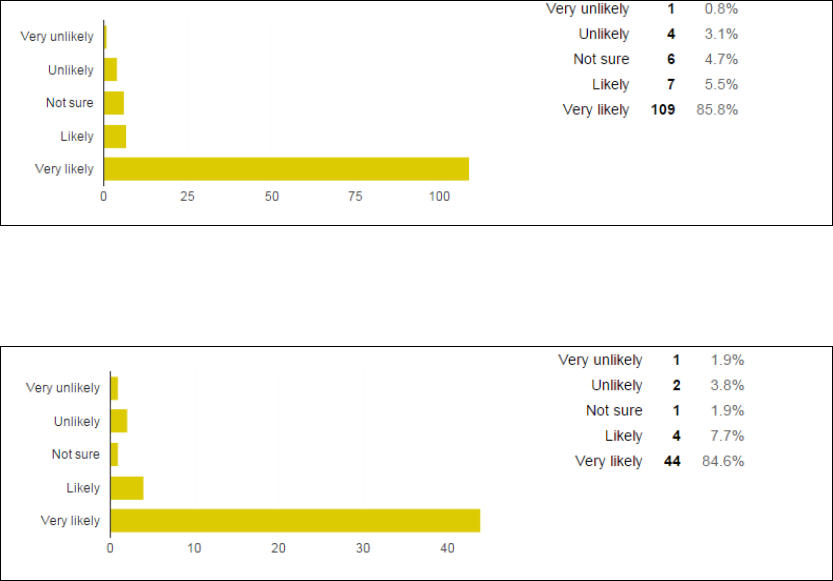

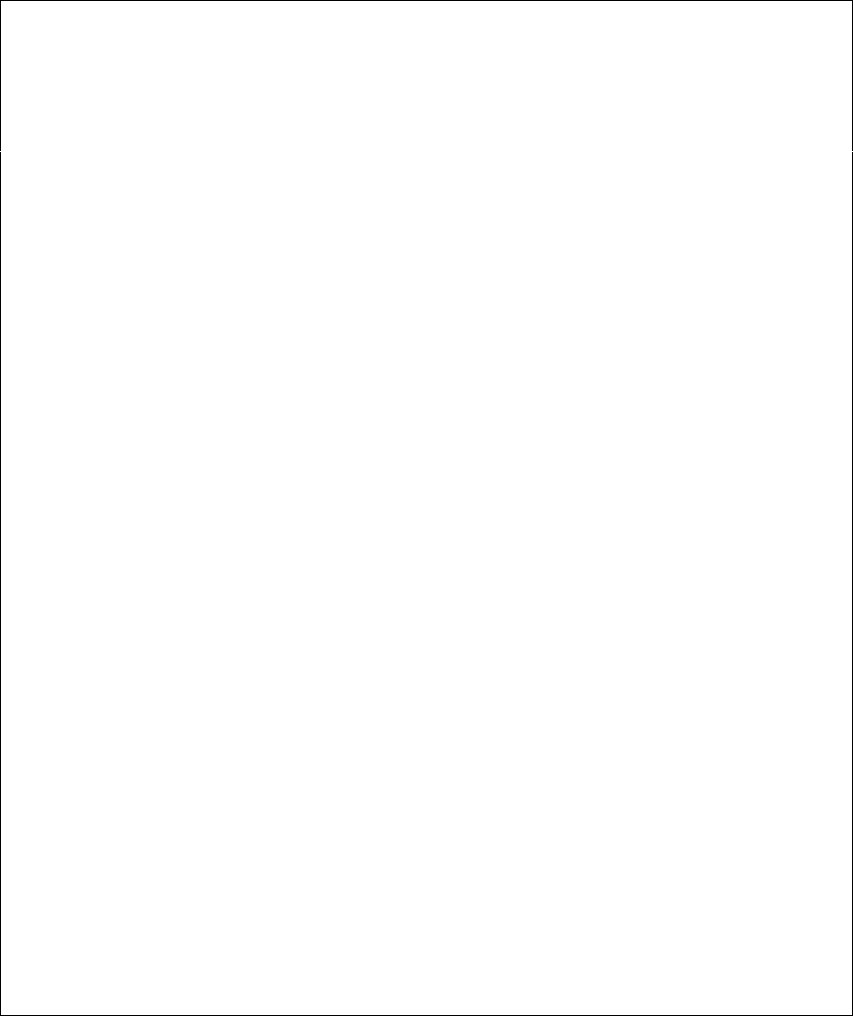

Figure 11: EISU EAP Tutors’ responses to Question 2 (n=12)............................................. 99

Figure 12: BALEAP list EAP Tutors’ responses to Question 2 (n=127)............................... 99

Figure 13: ELAL MA Distance programme responses to Question 2 (n=53) ..................... 100

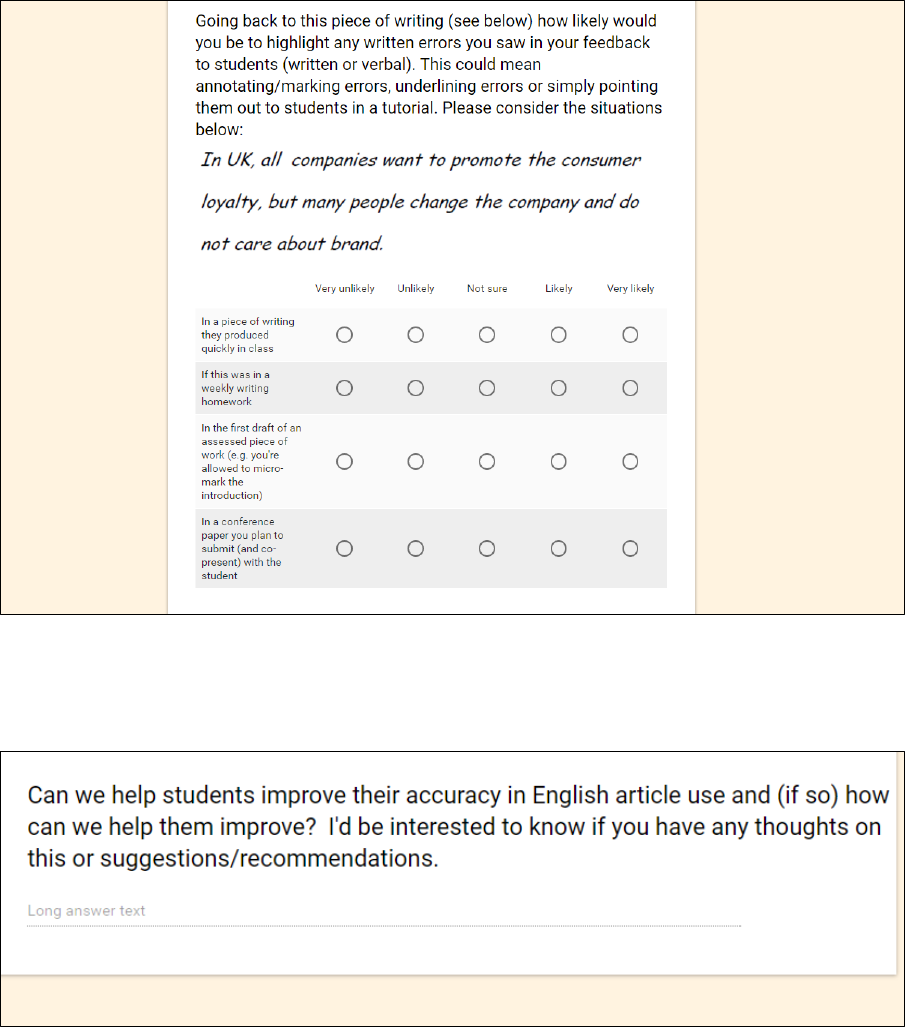

Figure 14: Question 3 prompt ............................................................................................ 101

Figure 15: EISU EAP Tutors Question 3 (in class) n=12 ................................................... 102

Figure 16: BALEAP EAP Tutors Question 3 (in class) n=120 ........................................... 102

xiv

xv

Figure 17: ELAL MA Distance programme Question 3 (in class correction) n=52 ............ 102

Figure 18: EISU Tutors Question 4 (weekly homework) n=12 ......................................... 103

Figure 19: BALEAP EAP Tutors Question 3 (weekly homework) n=127 .......................... 103

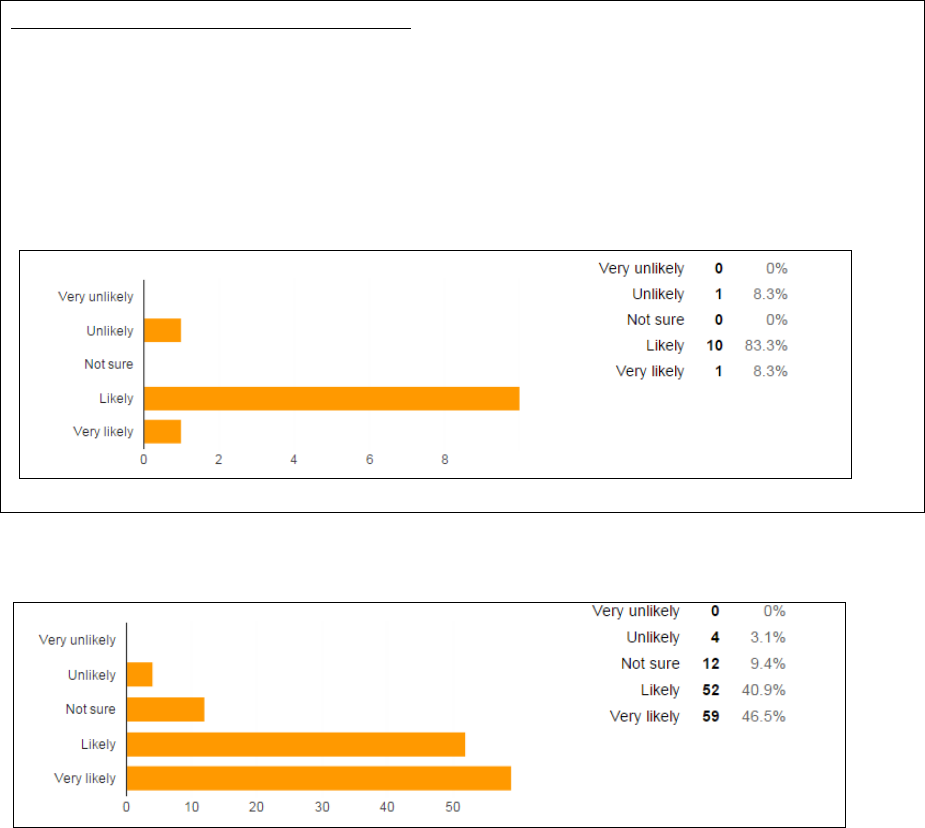

Figure 20: ELAL MA Distance Programme Tutors Q.3 (weekly homework) n=53 ............ 104

Figure 21: EISU Tutors Question 3 (in first draft) n=12................................................... 104

Figure 22: BALEAP EAP Tutors Question 3 (in first draft) n=127 .................................... 105

Figure 23: MA list tutors Question 3 (in first draft) n=52 ................................................. 105

Figure 24: BIA EAP Tutors Question 3 (conference paper) n=12 ..................................... 105

Figure 25: BALEAP EAP Tutors Question 3 (conference paper) n=127 ............................ 106

Figure 26: MA List Tutors Question 3 (conference paper) n=52 ........................................ 106

Figure 27: Transcribed extract Tutor #1 ............................................................................ 108

Figure 28: Transcribed extract Tutor #2 ............................................................................ 110

Figure 29: Transcribed extract Tutor #3 ............................................................................ 112

Figure 30: Transcribed extract Tutor #4 ............................................................................ 114

Figure 31: Transcribed extract Tutor #5 ............................................................................ 115

Figure 32: Tutor #5 continued ........................................................................................... 116

xvi

xvii

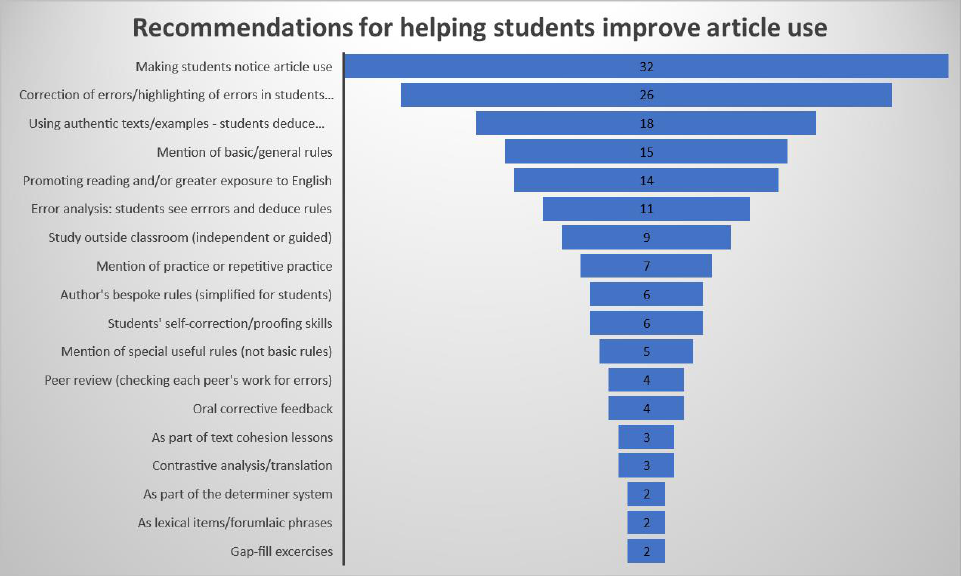

Figure 33: BALEAP list pedagogical recommendations (number of mentions, n=101) ...... 117

Figure 34: Transcribed extract Tutor #6 ............................................................................ 118

Figure 35: Reasons given for not teaching articles explicitly (n=101) ................................ 121

Figure 36: Three group experimental design ...................................................................... 129

Figure 37: Policy of tagging for correctness ...................................................................... 148

Figure 38: Example 1: Identification of error problems .................................................... 149

Figure 39: Example 2: Overt errors ................................................................................... 150

Figure 40: Example 2 from annotator instruction materials ................................................ 152

Figure 41: Oversuppiance issue disagreements .................................................................. 153

Figure 42: Appropriacy for genre disagreements ............................................................... 153

Figure 43: Disagreements about whether Type 3 or Type 4 ............................................... 154

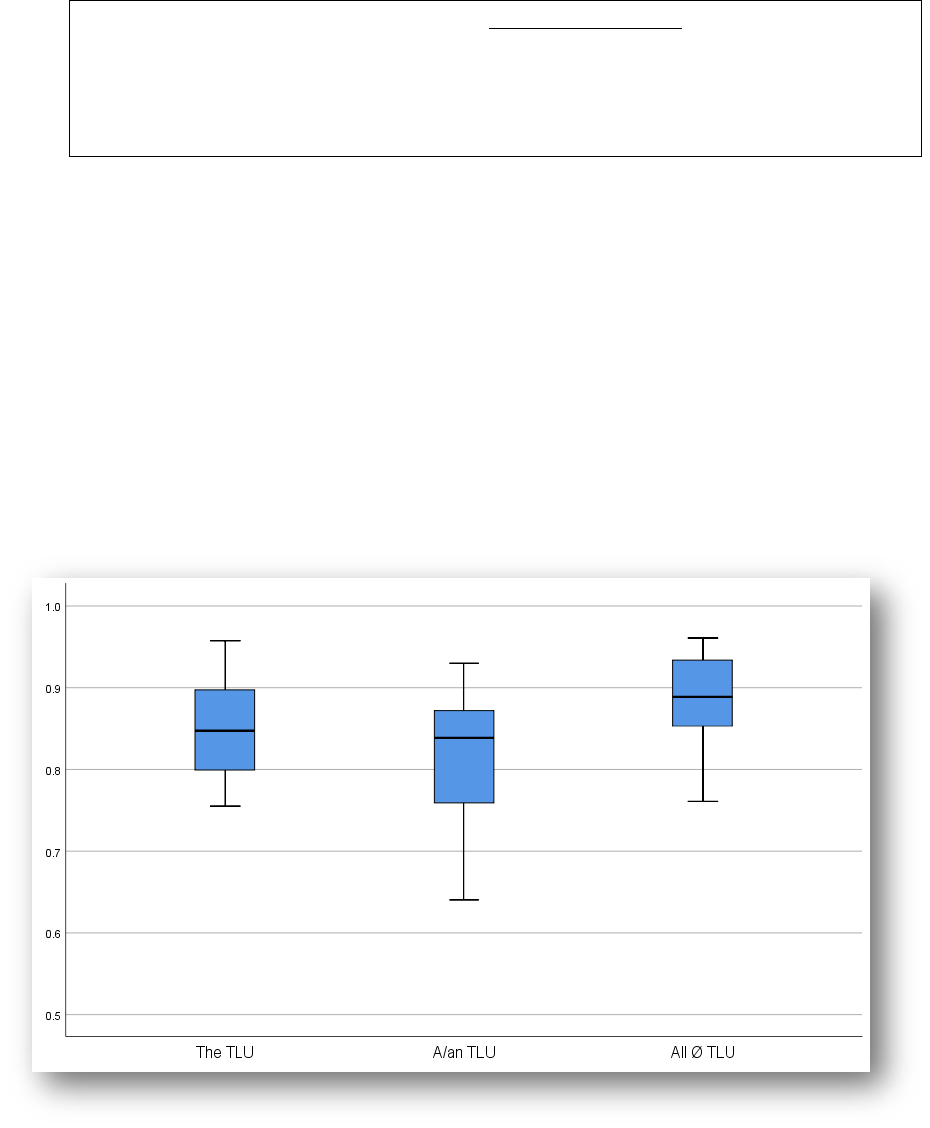

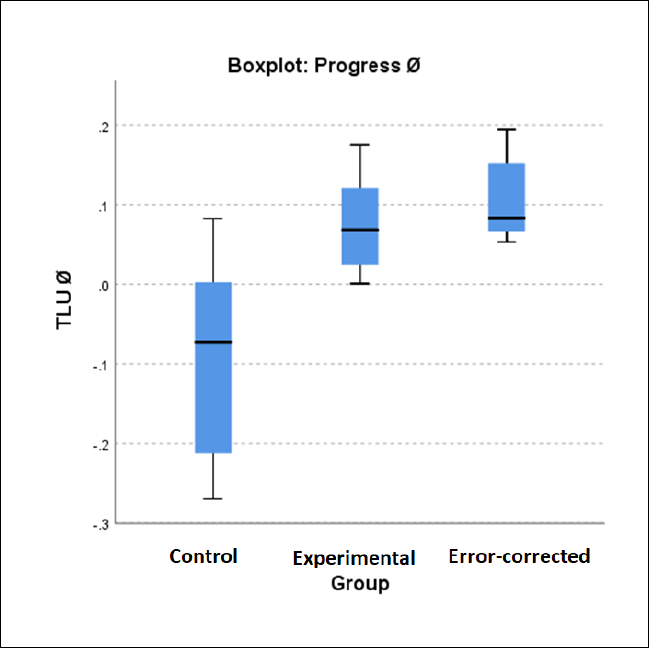

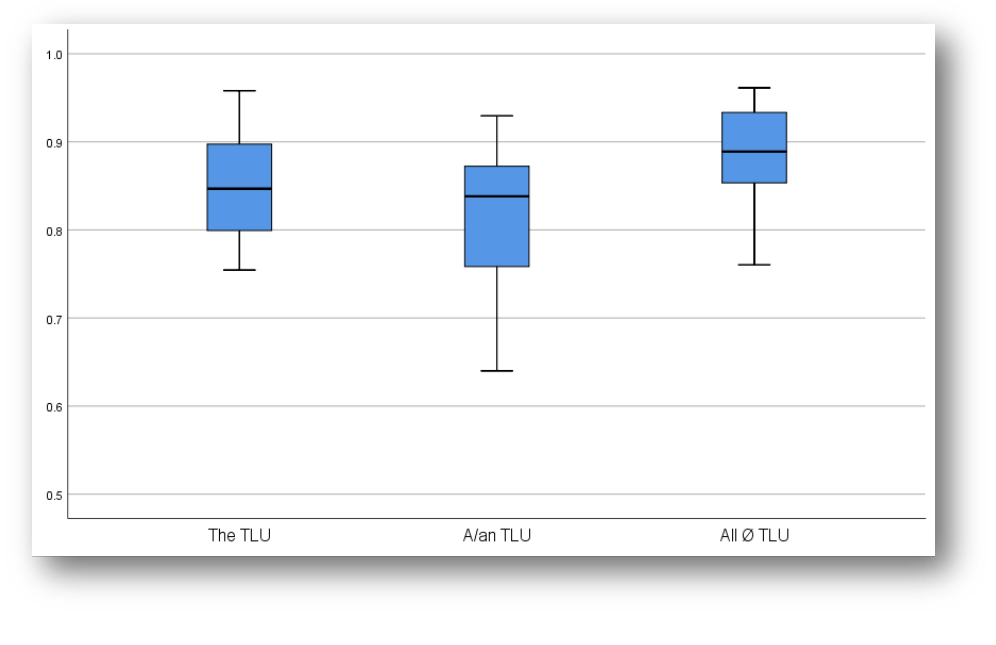

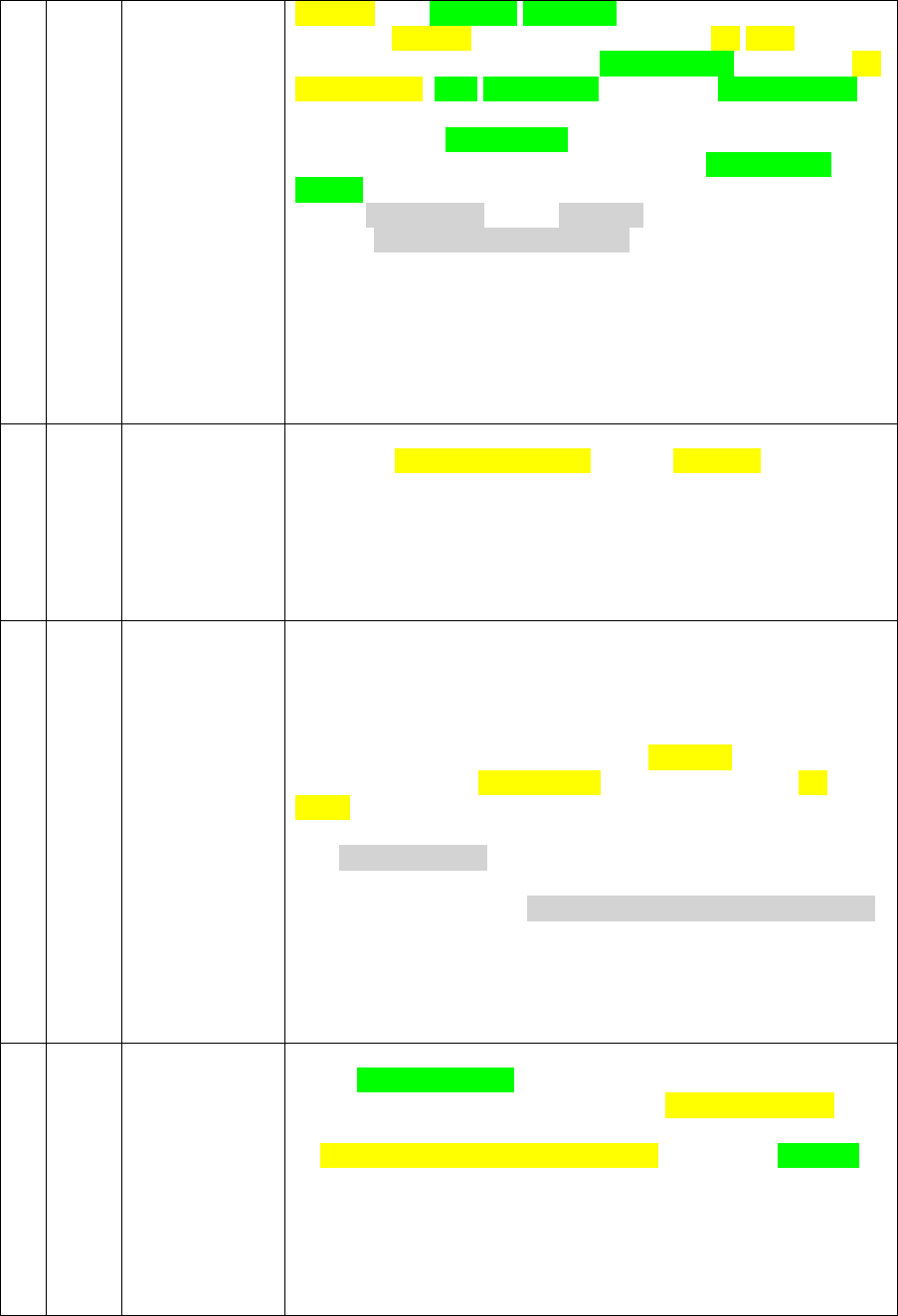

Figure 44: Box plot showing distributions of median TLU scores (n=24) ......................... 154

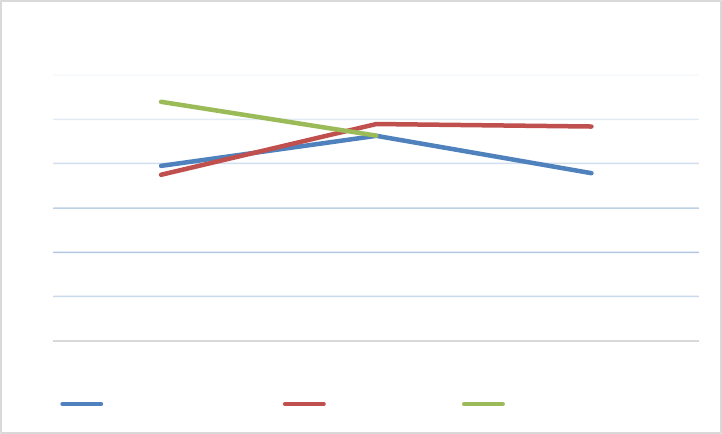

Figure 45: Target-Like Use of definite article (Type 1, 2 and 5 combined) ....................... 157

Figure 46: Target-Like Use of Ø (Types 1, 3, 4 and 5 combined) ...................................... 158

Figure 47: Target-Like Use of a/an (Types 1, 3 and 5 combined) ...................................... 158

Figure 48: TLU of 2DA definite article (n=24, all participants by group) .......................... 159

Figure 49: Progress by three groups (Mdn TLU of Ø) n=24 .............................................. 164

xviii

xix

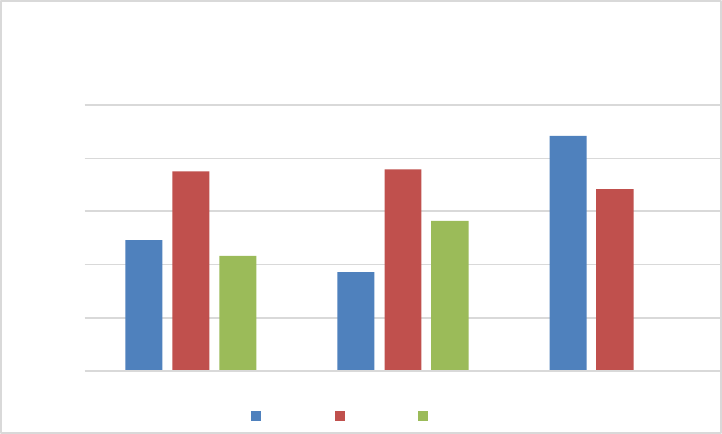

Figure 50: Bar chart – omission and oversuppliance of definite articles in Task 1 .............. 166

Figure 51: Bar chart – omission and oversuppliance of definite articles in Task 2 .............. 166

Figure 52: Participant responses to Survey Question 3 (n=23) ........................................... 169

Figure 53: Participant responses to Survey Question 4 (n=23) ........................................... 170

Figure 54: Tutor examples................................................................................................. 189

Figure 55: Student examples ............................................................................................. 189

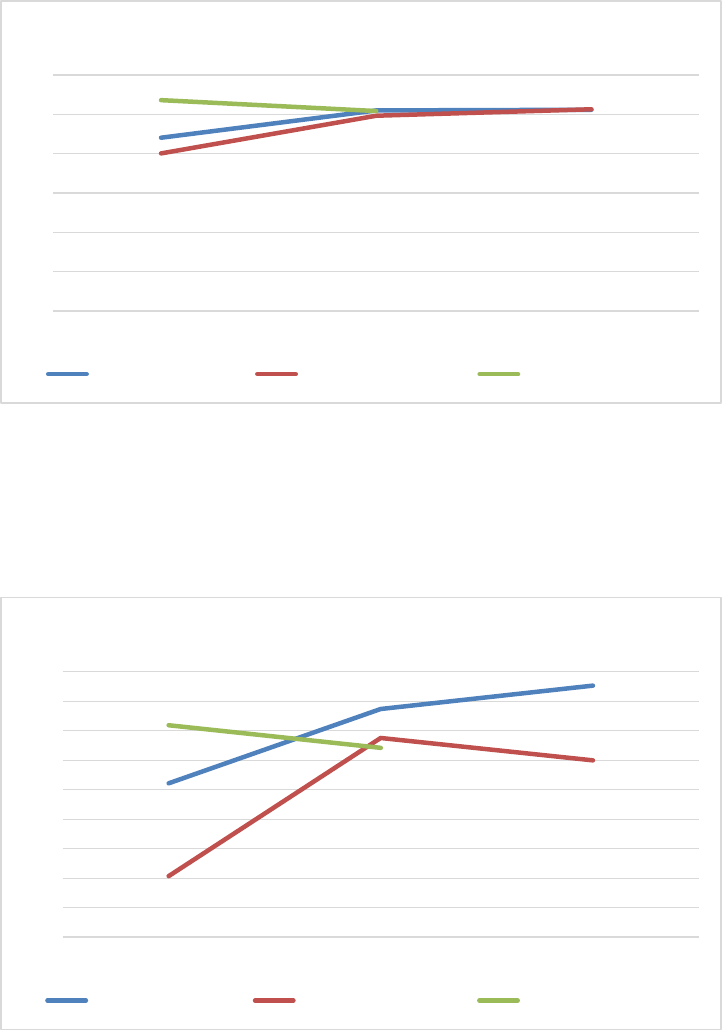

Figure 56: Median TLU scores in the three article types (3 prompts, n =24). ..................... 191

Figure 57: 2GADA errors compared to 2DA correct use ................................................... 197

Figure 58: 4GAZA errors compared to 4ZA correct use .................................................... 200

Figure 59: 4GAIA errors compared to 4IA correct use ...................................................... 202

Figure 60: 3GAIA errors compared to 3IA correct use ...................................................... 204

Figure 61: 5GADA errors compared to 5DA correct use ................................................... 206

Figure 62: 1GADA errors compared to 1DA correct use ................................................... 207

Figure 63: 3GAZA errors compared to 3ZA correct use .................................................... 208

Figure 64: 1GAIA errors compared to 1IA correct use ...................................................... 210

Figure 65: 5GAIA errors compared to 5IA correct use ...................................................... 211

Figure 66: Omissions of article with nouns pre-qualified with proper nouns ...................... 213

xx

xxi

Figure 67: Typical omission and oversuppliance errors (with pre-modified head nouns) ... 214

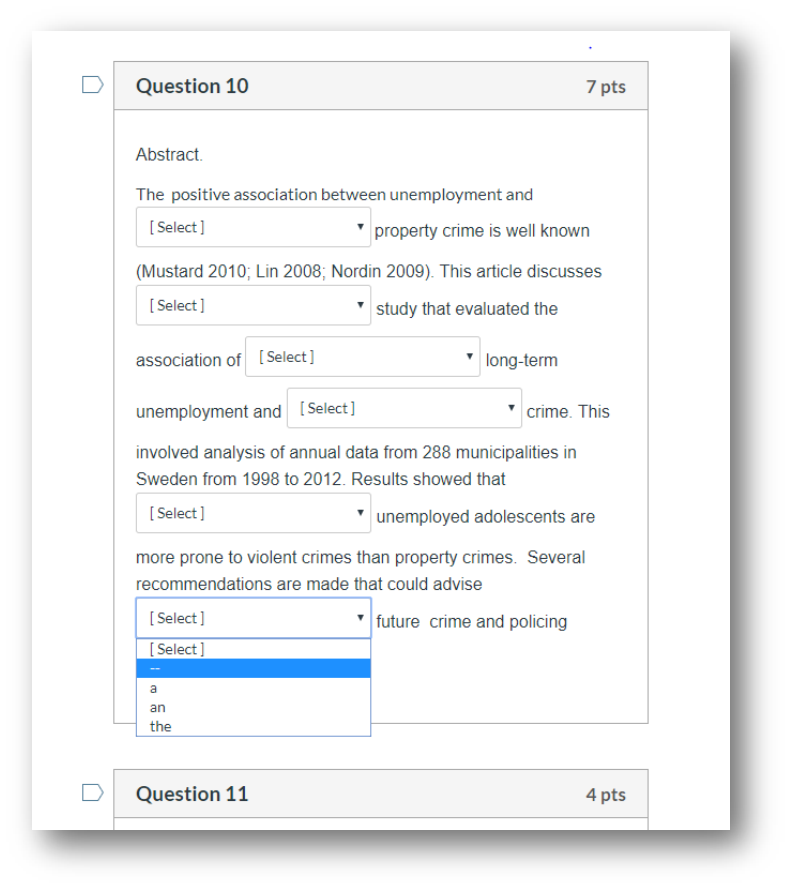

Figure 68: Example of question development (Question 10) .............................................. 227

Figure 69: Example of multiple dropdown question .......................................................... 228

Figure 70: Paired noun phrase examples ............................................................................ 229

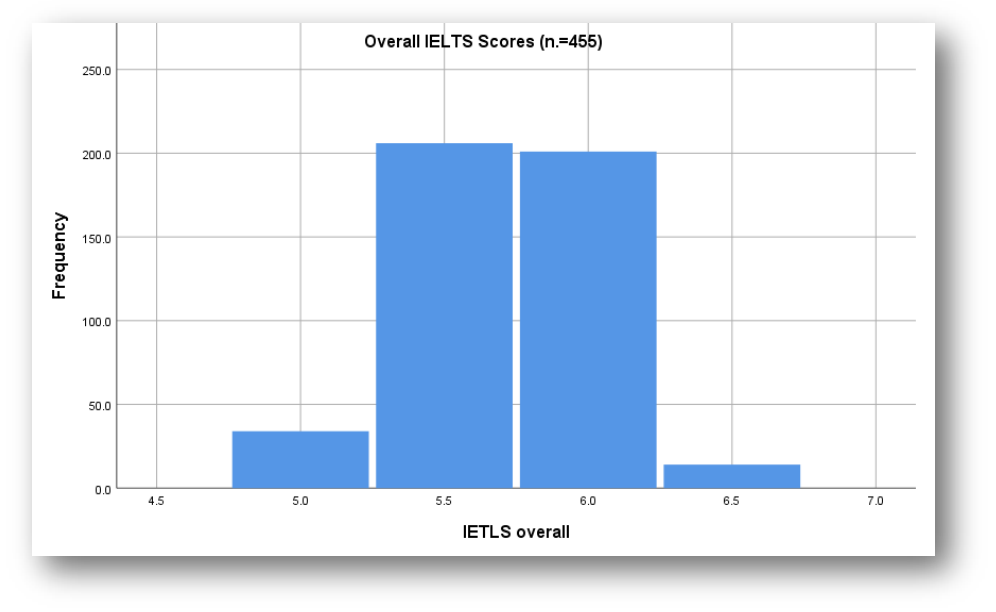

Figure 71: Histogram showing overall IELTs scores ......................................................... 233

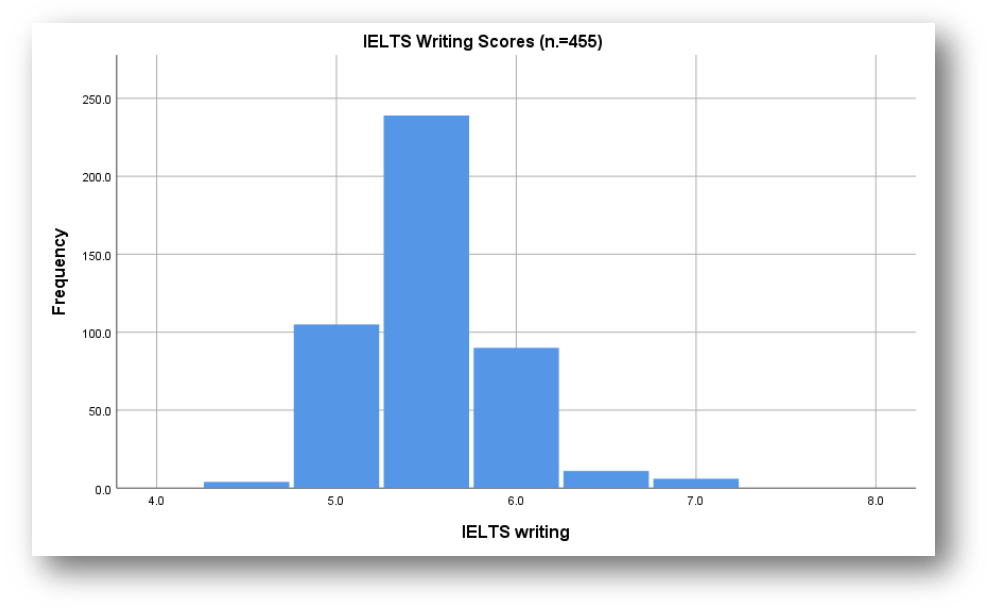

Figure 72: Histogram showing IELTS writing test scores .................................................. 234

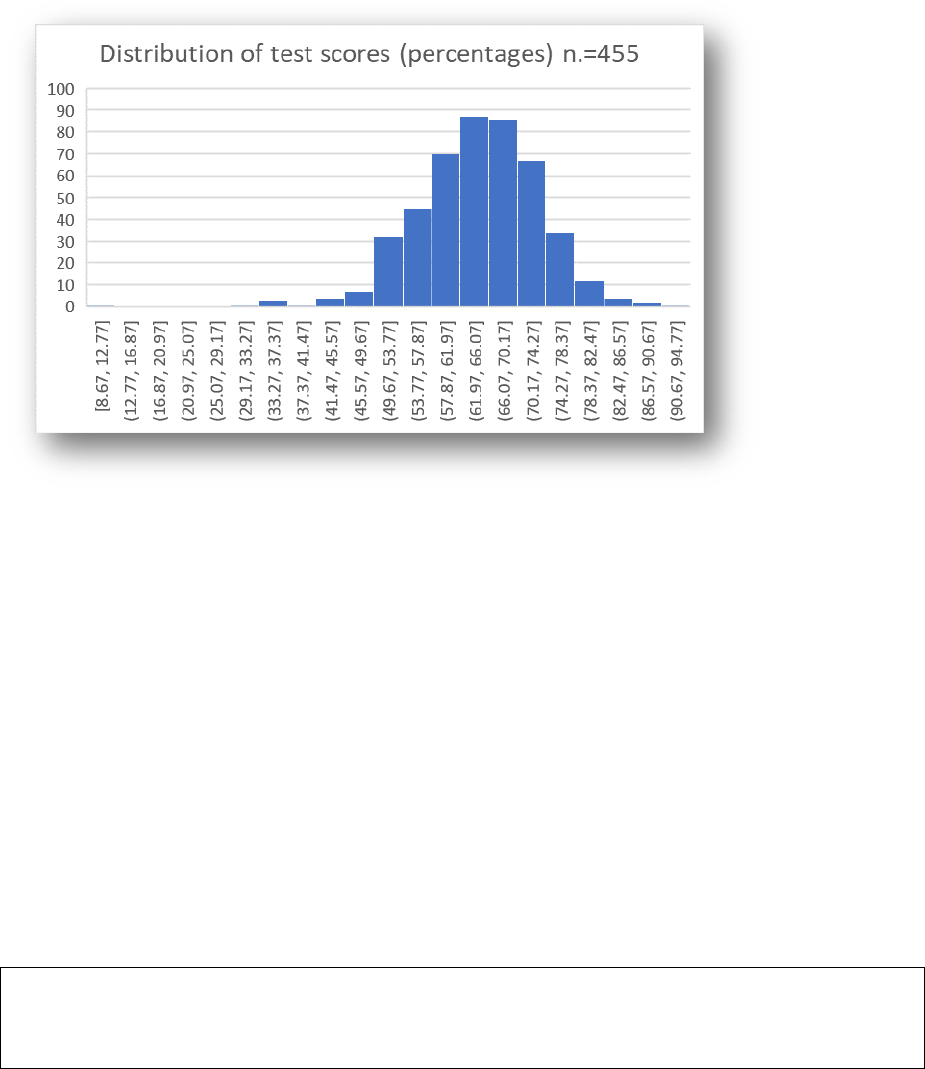

Figure 73: Histogram of test scores ................................................................................... 235

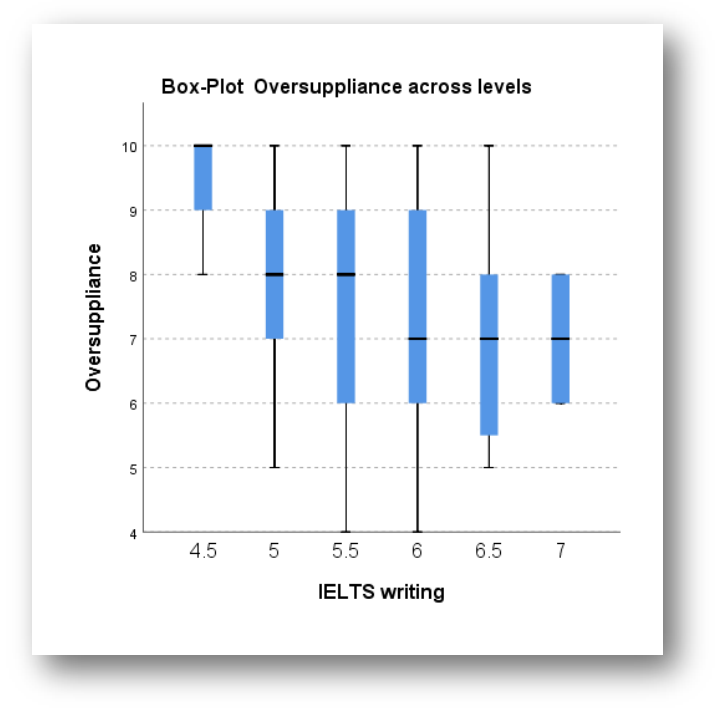

Figure 74: Oversuppliance (ten questions) box-plot (n=455) ............................................. 237

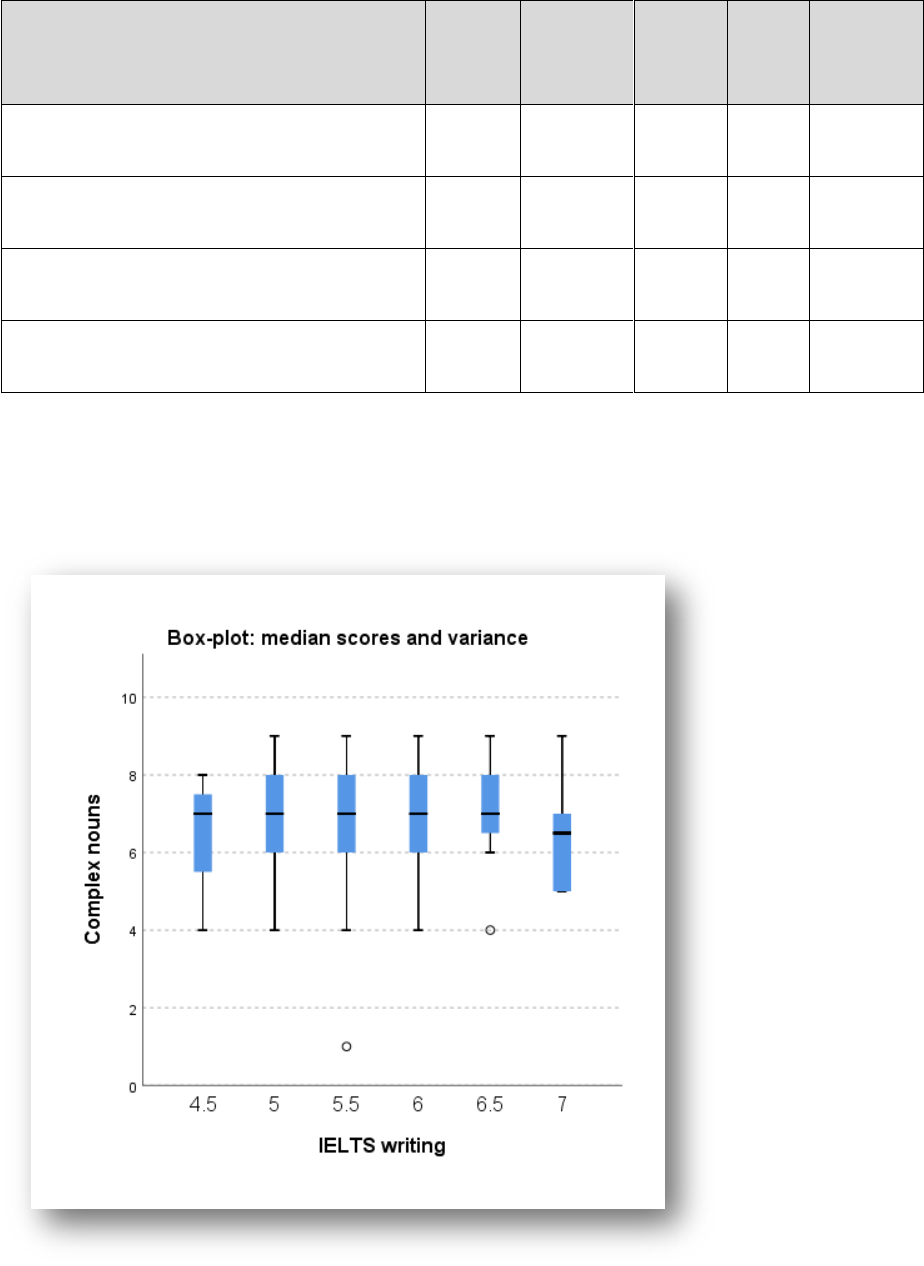

Figure 75: Boxplot of omission rates (grouped by proficiency) in complex noun phrases .. 240

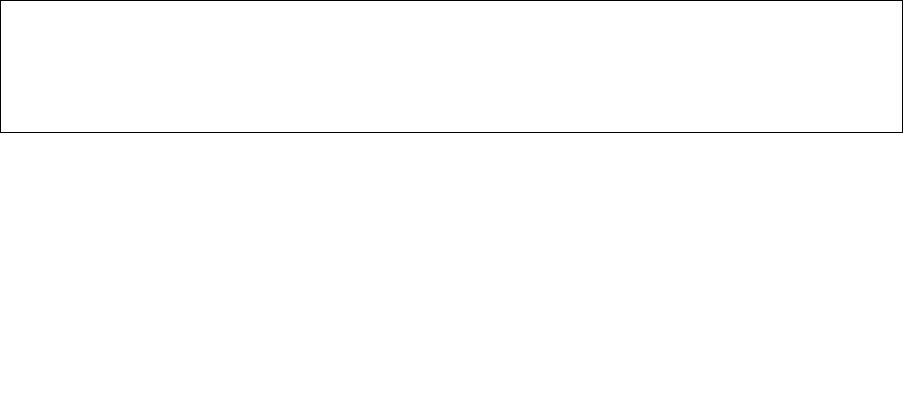

Figure 76: The relationship between general writing ability and overall test scores (n=455, 100

question items) .................................................................................................................. 242

Figure 77: Mapping specific-general functions of lexis to research project structure .......... 261

Figure 78: Deduced uses by Chinese L1 Engineering student [anonymised] ...................... 262

Figure 79: Student 1, conversation #1 ............................................................................... 324

Figure 80: Student 1, conversation #2................................................................................ 325

Figure 81: Student 1, conversation #3................................................................................ 325

Figure 82: Student 1, conversation #4 ............................................................................... 326

Figure 83: Student 1, conversation #5................................................................................ 326

xxii

xxiii

Figure 84: Student 1, conversation #6................................................................................ 327

Figure 85: Student 2, conversation #1................................................................................ 328

Figure 86: student 2, conversation 7 ................................................................................. 328

Figure 87: Student 2, conversation 8 ................................................................................. 329

Figure 88: Student 2, conversation 9................................................................................. 329

Figure 89: Student 2, conversation 10 ............................................................................... 330

Figure 90: Student 3, conversation 11................................................................................ 331

Figure 91: Student 3, conversation 12................................................................................ 332

Figure 92: Student 3 conversation 13................................................................................. 332

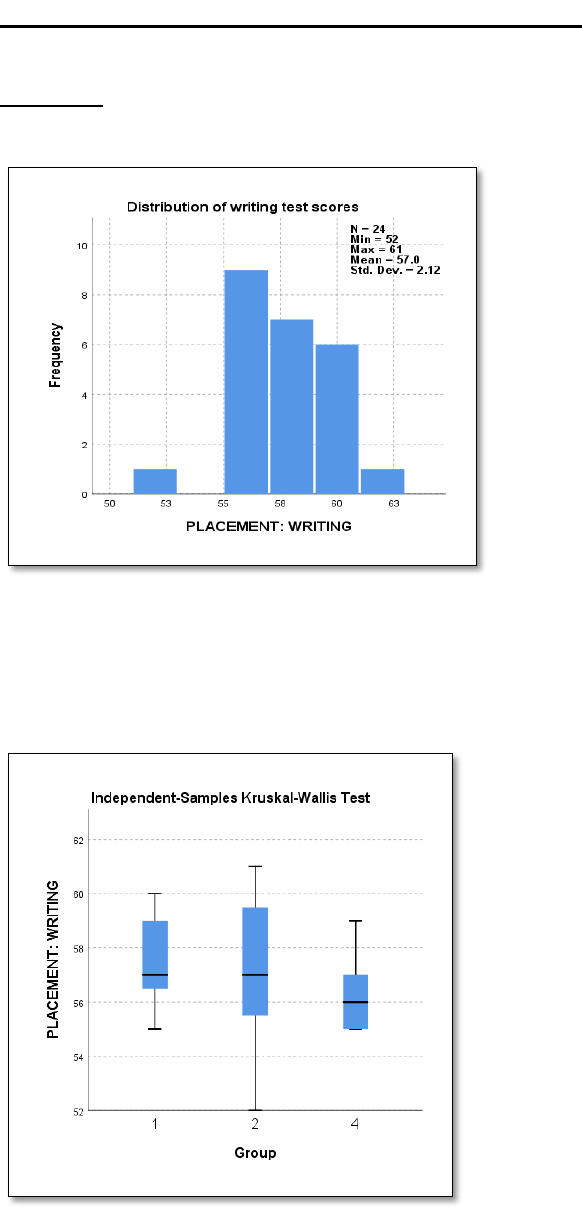

Figure 93: Distribution of written placement test scores (Chapter 5) ................................. 341

Figure 94: Distribution of student scores in the placement test........................................... 341

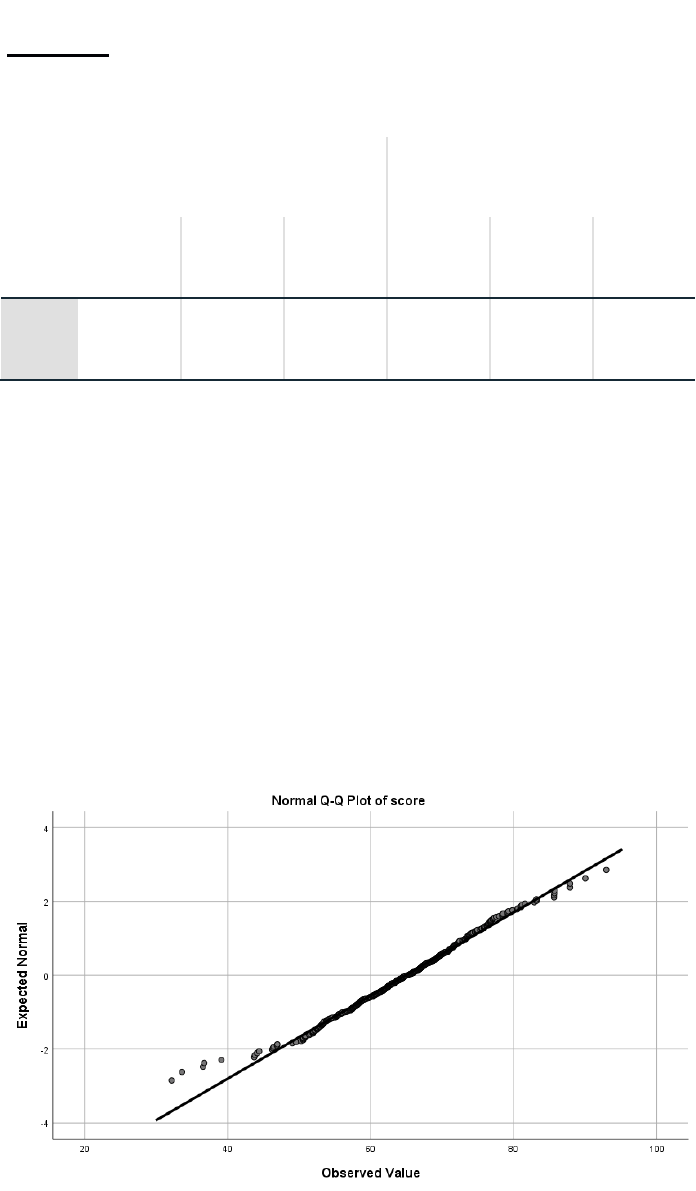

Figure 95: Test of normality (Q scores) ............................................................................. 342

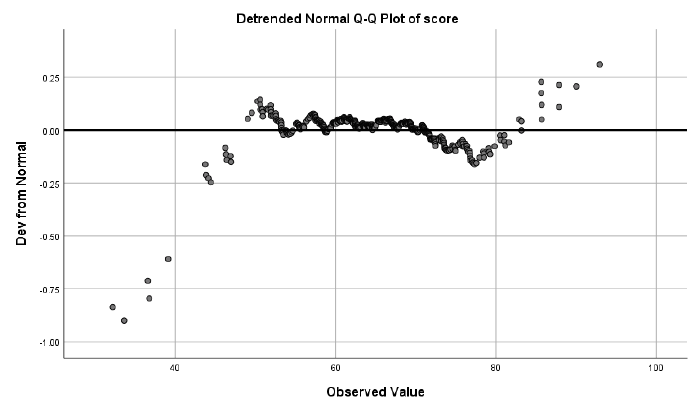

Figure 96: Tests of Normality (Detrended Q scores) .......................................................... 343

xxiv

xxv

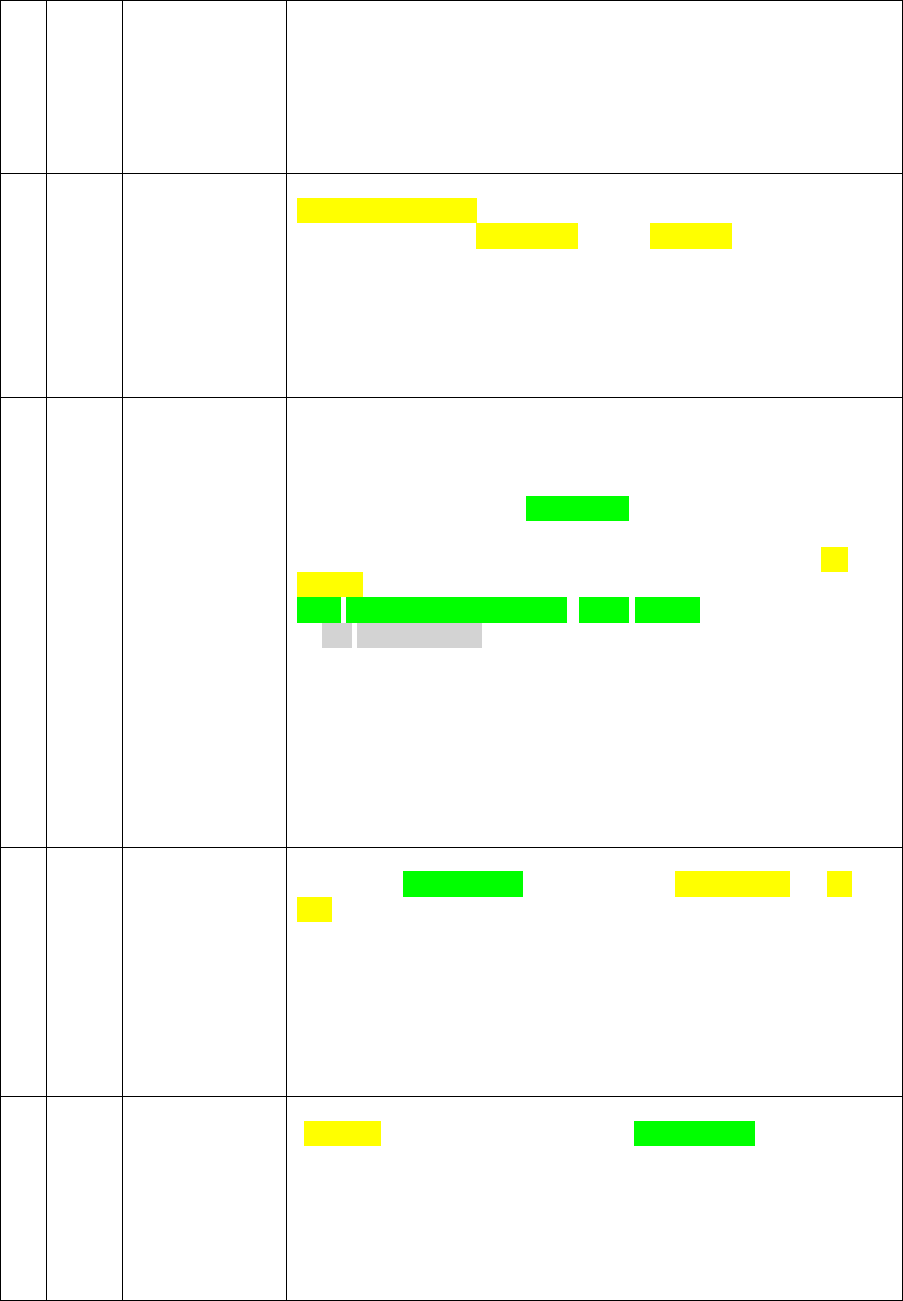

Table of Tables

Table 1: Bickerton’s (1981) semantic and pragmatic Framework ........................................ 18

Table 2: A comparison of important corpus findings ........................................................... 41

Table 3: Error Analysis Steps/common methodological issues ............................................ 60

Table 4: Review of influential article acquisition/corpus-based studies ................................ 68

Table 5: Five learner corpus studies compared .................................................................... 72

Table 6: IELTS score descriptions (from IELTS, 2012) ....................................................... 82

Table 7: Response rates ....................................................................................................... 95

Table 8: Participant information ........................................................................................ 133

Table 9: Essay prompts ..................................................................................................... 136

Table 10: BME Teaching materials ................................................................................... 139

Table 11: Five extra English article sessions...................................................................... 141

Table 12: Tagging system for correct uses (Díez-Bedmar & Papp, 2008) .......................... 146

Table 13: Tagging system for incorrect uses (Díez-Bedmar & Papp, 2008) ....................... 146

Table 14: TLU ratings for all groups summarised (n=24) with no adjustment .................... 155

Table 15:TLU ratings all groups (n=24) with adjustments* for zero counts ....................... 156

Table 16: Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test *=statistically significant at 0.05 .......................... 160

xxvi

xxvii

Table 17: Omission and Oversuppliance of definite articles (all types, Mdn coefficients*) 165

Table 18: Misuse of article errors ...................................................................................... 167

Table 19: Participant information (including borderline B1/B2 students). .......................... 181

Table 20: Four Task prompts ............................................................................................. 183

Table 21: Framework adapted from Bickerton’s (1981) semantic and pragmatic uses ........ 185

Table 22: Proportion of errors by context .......................................................................... 187

Table 23: L1 writers (n=5) article uses compared to Chinese L1 essays (n=24) ................ 188

Table 24: Overall TLU (all essays) in all contexts (n=24) ................................................. 192

Table 25: TLU is essay prompts compared to case study prompt ...................................... 194

Table 26: The effect of pre-modification ........................................................................... 199

Table 27: Density of noun phrases (in 610 article errors) ................................................... 212

Table 28: Analysis of 9186 correct noun phrases ............................................................... 212

Table 29: Results of ten questions investigating oversuppliance (n=455) ........................... 236

Table 30: Articles omitted in twenty nominal groups (with and without pre-modification) 239

xxviii

1

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Brief overview

This PhD research stems from an interest in one of the most confusing and frequent

grammatical choices that learners of English must make: whether to use the, a/an, or no article

(Ø) in written production. The is by far the most commonly occurring word in the English

language (Sinclair, 1991) and, since the most frequent choice is not to use any determiner, the

Ø article has been argued to be the most frequently occurring free morpheme (Master, 1997).

On the assumption that accuracy is considered important, a focus on these small words in

English for Academic Purpose (EAP) classes appears necessary, as it has long been pointed

out that the/a/an together account for more than one in every ten words in academic writing

(Berry, 1991).

While the complexities of the English article system are likely to challenge all international

students whose first language is not English, the literature suggests that students from a first

language (L1) background that does not grammaticalise definiteness/specificity may face

particular challenges in applying certain aspects of the English article system (Master, 1997;

Lu, 2001; Ekiert, 2004; Díez-Bedmar & Papp, 2008; Snape, Mayo & Gürel, 2013; Crosthwaite,

2012, 2016a). The extent to which Chinese Mandarin grammaticalises these notions will be

discussed in Chapter 2, but some researchers have claimed that Chinese learners’ first language

affects their use of the/a/an/Ø in academic writing at university at Upper-Intermediate levels

of English proficiency (Milton, 2001; Chuang & Nesi, 2006; Díez-Bedmar & Papp, 2008; Lee

& Chen 2009). Indeed, it has been suggested that article errors (omission and overspecification

of the definite article) are the most commonly occurring grammatical errors made in English

academic writing by Chinese L1 undergraduate university students (Chuang & Nesi, 2006).

The increase in the numbers of Chinese L1 students in UK Higher Education over the past 15

2

years (see Section 1.3.1) has further heightened the need to understand these students’

challenges with English articles in academic writing.

Having briefly outlined the topic, this chapter now has four aims: to explain my personal and

professional interest in this research, to justify this interest in academic terms, to highlight why

further research is necessary and to outline the structure of this thesis.

1.2 Personal interest

My curiosity regarding EAP students’ article usage can first be explained anecdotally. In my

observations of over 30 EAP teachers in my role coordinating an English for Academic

Purposes Presessional at a UK university (some of whom were new entrants to EAP from the

fields of English as a Foreign Language and English as a Second Language), it has been my

personal experience that the English article system can be taught effectively by EAP tutors. As

will be illustrated in Chapter 4, which presents a survey of English for Academic Purposes

(EAP) tutors’ beliefs and practices regarding the teaching of English articles, many tutors

manage to focus students on accurate article use in authentic academic texts in ways which

motivate students and promote learner autonomy. However, my experience over 14 years of

teaching EAP suggests that some tutors are unsure about whether they can and how they should

improve students’ accuracy in English articles. Can and should they teach article use? If so,

which aspects of the article system challenge Chinese L1 learners most? Should they correct

article errors in academic writing feedback and does this help learners or simply discourage

them?

Unfortunately, some EAP tutors have not stopped to even ask the questions above. In a

depressingly similar fashion to my own experiences as a learner of second languages, I have

also sometimes noticed students being overcorrected and discouraged, taught rules they already

3

learned in middle school, made to complete decontextualised grammar gap-fill exercises that

may have little effect on written production, told oversimplified rules and even provided with

incorrect advice and feedback.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some tutors totally avoid focussing on the English article

system in EAP. As discussed in Chapter 4, possible causes can include a tutor’s lack of

confidence of their own understanding of the article system, some tutors’ belief that students

can naturally improve article accuracy without intervention, a principled objection to focussing

on form within EAP, or a perception that article errors are trivial surface errors. Irrespective

of the tutors’ beliefs, many also perceive that they have insufficient time to devote to this minor

error in the typical EAP curriculum in which the need for accuracy of articles has to compete

with many more important priorities. Moreover, given that genre analysis, register awareness,

and many competing lexico-grammatical areas are simpler to teach and have proven efficacy,

many tutors need convincing that a focus on article accuracy could and should merit occasional

attention in the EAP classroom.

Although the personal anecdotal evidence presented above is not proposed to support the

claims made in this thesis, these experiences underpin my personal and professional motivation

for addressing the topic. The following section will present the more academic background to

this issue before summarising the aims of this thesis: to give EAP tutors greater clarity on

whether they can and how they can facilitate improved English article accuracy among Chinese

learners.

4

1.3 Background and justification for the research

1.3.1 Justification for the focus on Chinese L1 Postgraduate level students

The focus on the English article use of Chinese L1 international students at postgraduate level

is justified due to the massive expansion of Chinese L1 students studying in many UK HE

institutions over the last 15 years (Universities UK, 2019). According to this source, 19.6% of

the total UK student population in 2017/18 were international students making a net worth

contribution to the UK of £20.3bn. Of these 458,490 international students, 106,530 came

from China and this figure has been rising steadily since 2013. Over 70% of students in the

summer Presessional English for Academic Purposes Programme at the author’s own

institution are Chinese L1 students who progress onto postgraduate programmes in which they

often outnumber home students, notably in the university’s Business and Engineering Schools.

This reflects broader national trends, for which current data indicate that the majority of

postgraduate Chinese speaking students enrol onto Business studies, Economics, Accounting

and Finance, and Engineering programmes at UK universities (The Higher Education Statistics

Agency, 2019). It thus seemed appropriate to focus on Chinese L1 Business School students in

the studies presented in Chapter 5 and 6. These official UK statistics may already be out of date

according to a recent Guardian Newspaper report (Weale, 2019) which suggests that

applications for study in the UK 2019/20 have increased by 30% due to China-US tensions. It

is therefore more relevant than ever to understand any L1 effects upon language inaccuracy.

The question of whether Chinese students could be assisted to improve their English article

accuracy is also related to the instruction provided within the university setting and the

following section therefore provides the definition and background of English for Academic

Purposes (EAP).

5

1.3.2 English for Academic Purposes (EAP)

Rather than being defined simply as English lessons in a university setting, English for

Academic Purposes (EAP) is generally argued to be a separate paradigm of instruction (Swales,

1990; Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001; Hyland & Hamp-Lyons, 2002; Alexander, Argent &

Spencer, 2008). Linked to the greater use of English across the world by non-native speakers

of English (Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001), the proliferation and expansion of EAP courses in

the UK is also related to the internationalisation strategies of many UK universities. In the UK

context, the term EAP covers a broad range of activities including highly specific courses

embedded within disciplines; presessional courses designed for students who have not reached

the English proficiency entry requirements and need to show some progress before starting

their intended academic programme; insessional classes covering a ‘core skills’ approach

offered to all students during their programme, and new forms of integrated academic English

skills and content instruction such as Foundation programmes. The core defining feature of

any EAP course is that the objectives are needs-focussed with the aim to help international

students achieve success in their intended academic community (Hyland & Hamp-Lyons,

2002).

Any discussion about whether English article accuracy can be a focus in the EAP curriculum

needs to recognise the competing demands for any EAP tutor’s time in the classroom. As will

be developed in Chapter 2, a focus on language forms such as the/a/an/Ø needs to be integrated

within a curriculum which has an arguably greater priority of preparing students for the

functions and processes of academic writing. While most EAP Presessional courses offer a

mixture of general and academic English, EAP is often defined by its more dominant focus

on the socialisation of students within their discourse communities which involves special

attention to the genres of writing that students will be producing in these communities (Swales,

6

1990; Swales, 2004; Swales & Feak, 2004) and the many variances in genre across disciplines

(Hyland, 2002a, 2007b; Nesi & Gardner, 2012). In contrast to the general English syllabus

which prepares students for English language demands in their entirety (an integrated syllabus

which tends to recycle grammatical accuracy issues over shorter texts of various topics), the

‘EAP paradigm’ involves more time restricted programmes on academic English more

focussed on writing and reading (Alexander, Argent, & Spencer, 2008). This generally entails

deeper exploitation of a smaller number of denser academic texts (ibid.). With regards to

grammatical features such as English articles, an ‘EAP paradigm’ could thus be expected to

include such a focus more incidentally than general English, as and when needed, if at all

(reference will be made to the researcher’s programme in Chapter 5).

While acknowledging that some researchers continue to see accuracy in articles as acquired

naturalistically without instruction (Alexander, Argent, & Spencer, 2008), this thesis makes the

assumption that a focus on form in language generally accelerates accuracy. In EAP’s related

sister field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) the consensus view for the past 35 years

has rejected theories of naturalistic L2 language learning of the written form of L2 (Long, 1983,

1990; Norris & Ortega, 2000; Ellis, 2006). The generally accepted view in SLA research is that

students need both content-driven ‘comprehensible input’ (Dulay, Burt & Krashen, 1982;

Nunan, 1991) in addition to a focus on form that helps learners notice patterns more

consciously (Norris and Ortega, 2000; Ellis, 2006). However, the assumption that a focus on

form has theoretical benefits should not be confused with a traditional decontextualised

approach to grammar teaching. This thesis in no way seeks to argue for a return to the

behaviourist and prescriptively ill-informed approaches of writing composition classes in the

1960s and 1970s (Paltridge, 2001). More realistically, the investigations into the effects of

different methods of teaching articles were carried out on the theoretical assumption that form-

7

focussed instruction can sometimes contribute to students’ noticing of written accuracy. This

assumption would appear solidly grounded on theory since the total rejection of any focus on

grammar is less common today in the EAP field and many EAP researchers conclude that an

incidental focus on form integrated within an EAP genre-based approach can be beneficial

(Hyland & Milton, 1997; Hinkel, 2003; Fang, Schleppegrell & Cox, 2006; Hyland, 2008).

One unresolved polemic within the EAP literature, more directly affecting the topic of this

research, relates to written error correction. The review of the literature in Chapter 2 will more

critically juxtapose the research that supports focussed written corrective feedback (Ellis, 1994;

Polio, Fleck & Leder, 1998; Ferris, 1999; Chandler, 2003; Bitchener, Young & Cameron, 2005;

Dale, Anisimoff & Narroway, 2012; Ferris & Kurzer, 2019) with research that questions the

value of the labour-intensive process of written corrective feedback (Truscott, 1996, 2004;

Crosthwaite, 2016b). Within EAP, Alexander, Argent, & Spencer (2008: 210) certainly

discourage the correcting of ‘every misuse of articles’. Thus, the practices I have anecdotally

witnessed during summer presessionals over 11 years of teaching and coordinating EAP

courses does not always appear to sit so harmoniously within the recommended practice of

EAP. It was therefore of interest to know why EAP teachers were so frequently seen to be

correcting article use and whether such correction served a purpose.

The justification of this thesis thus follows the practical objectives of past error analyses

(Corder, 1967; Master, 2002; Chuang & Nesi, 2006): to improve pedagogical approaches

through understanding. Through knowing the extent to which different contexts of article use

cause challenges for Chinese L1 learners and the reasons for which mastering some contexts

may prove more difficult, EAP pedagogy and materials development could be refined to better

suit these learners who are so highly represented in student numbers. However, as shall be

reviewed in the next section and the Literature Review, there are gaps in knowledge and

8

disagreement about the extent to which different article use contexts cause challenges for

Chinese L1 learners and even whether they continue to make frequent errors at Upper-

Intermediate levels of English proficiency.

1.4 Previous Research into Chinese L1 learners’ English article accuracy

The question of whether Chinese L1 university students make the most errors through definite

article omission (Chuang & Nesi, 2006; Díez-Bedmar & Papp, 2008) or through omission of

Ø/oversuppliance of the definite article (Lee & Chen, 2009) will be discussed further in the

next chapter and then investigated using both corpus methods and a testing approach. As the

Literature Review will show, previous studies have arrived at very different conclusions

regarding this question. While some researchers (e.g. Crosthwaite 2016a) have found that most

article contexts pose few challenges for Chinese students by the time they have reached Upper-

Intermediate levels, other researchers (e.g. Lee & Chen 2009) report frequent and meaningful

effects of article inaccuracy among Chinese majors in English and Applied Linguistics with

high levels of English.

As shall be presented in the next chapter, this thesis adopts a weak form of the Contrastive

Analysis Hypothesis. The assumption is made that learners with an L1 containing an article

system [+Article] could have a different ‘natural order of article acquisition’ to learners whose

language has no article system, but that this effect should not be oversimplified (as many other

factors affect acquisition and written accuracy). Master (1997: 216) found high levels of

inaccuracy among higher levels of article-less L1 background EAP students including Chinese

L1 learners and concluded that transfer effects were a large contributor. However, many EAP

tutors are likely to hold an overly simplified working hypothesis about the effect of L1 on their

Chinese students’ accuracy in academic English based on less evidence-based research. Over

many years, one hugely influential book has been Smith and Swan’s (2001) Learner English:

9

A teacher’s guide to interference and other problems, within which Chang’s (2001: 318)

chapter creates a somewhat negative impression of Chinese L1 writing with a strong

assumption of ubiquitous error through L1 transfer effects in L2 English:

There are no articles in Chinese. Students find it hard to use them consistently correctly. They

may omit necessary articles: *Let’s make fire *I can play piano. Or insert unnecessary ones:

*He finished the school last year. *He was in a pain. Or confuse the use of definite or

indefinite articles: *Xiao Ying is a tallest girl in the class. *He smashed the vase in the rage.

However, Chang provides little evidence to support such claims. In fact, as shall be discussed

in Chapter 2, more empirical recent research suggests that the L1 of Chinese students has a far

more complex and nuanced effect on their accuracy in different contexts of article use (Díez-

Bedmar & Papp, 2008; Crosthwaite, 2016a). These latter empirical findings are extremely

useful, particularly in the context of the competing demands for attention in the EAP syllabus

and the obvious benefit of focussing learners on specific article uses effectively, rather than on

the article system in its entirety. After reviewing this empirical research in Chapter 2, this

study will further investigate these nuanced effects and thereby contribute to the insights such

evidence can give to materials and syllabus designers in EAP.

The issue of whether article errors are minor surface errors that cause only annoyance or can

cause meaningful problems in communication is fundamental to the question of whether tutors

should attempt to teach accurate use of the/a/an/Ø articles in EAP. The issue of error gravity

(Corder, 1967) will thus need to be addressed in several chapters in this thesis. In addition to

discussing the effects of Chinese learners’ article morpheme errors in terms of sentence-level

accuracy, this research will also seek to explore the effect of article inaccuracy on the overall

register of students’ writing. Indeed, in recent years, some interest has been shown in the

writing errors that Chinese learners make (including articles, pronouns and adverbs) and the

effects these errors have on the reader’s perceived academic register of writing. A number of

10

studies have noted informal characteristics in the English academic writing of Chinese L1

university students (Mayor, 2006; Gilquin & Paquot, 2007; Lee & Chen, 2009; Chen, 2014).

Such claims are often refuted (see Leedham, 2015), but there is a possibility that this impression

is related to the observation made in the research that [-Article] L1 background students go

through a ‘flooding’ stage of definite article overuse in their acquisition process (Huebner,

1983; Master, 1997;Thomas, 1989; Zdorenko & Paradis, 2008), which has also been claimed

to be seen in Chinese L1 university students’ writing (Lu, 2001; Lee & Chen, 2009). It is

certainly possible that such effects are often overestimated in a similar way to how many EAP

tutors assume all article errors are due to L1 transfer effects, but this interference is an

interesting focus for research.

1.5 Summary of research aims

The intention is to further the EAP field’s understanding of the types of article use that cause

Chinese learners the most frequent challenges, in order to inform the development of more

targeted pedagogical resources relevant for Chinese learners in EAP. To develop this

pedagogy, a greater understanding is required not only of the errors that Chinese learners make,

but the causes of such errors (including L1 effects) and EAP tutors’ current approaches to

teaching article use. Another aim is therefore to understand the current attitudes and practices

of EAP tutors with regard to teaching and correcting article use. The findings of this research

could then help tutors to decide which article uses to teach or ignore and whether or not they

should correct errors in student writing. With a greater understanding of these article errors,

after briefly focusing learners on article forms, tutors could potentially focus students upon

self-correction and peer-marking which are more consistent with current student-centred

approaches that encourage learner autonomy. By investigating students’ accuracy and

teachers’ attitudes, the thesis inevitably touches on some of the ongoing debates in EAP.

11

Although not the main objective of this research, this thesis will contribute to the discussion

about whether an occasional focus on accuracy (morpheme choice) is fully compatible with

current approaches to teaching EAP recommended in the literature.

1.6 Thesis overview

Chapter 2

After reviewing the English article system and the effect of article errors in writing, a

contrastive analysis of Chinese Mandarin will be presented. The review of the research

literature will suggest some limited support for the L1 effect hypothesis, but also show a highly

complex range of factors affecting development and accuracy with English articles. Having

identified several gaps in the literature, the chapter summarises four Research Questions.

Chapter 3

While the procedural methodologies of the individual studies are presented in their individual

sections (Chapters 4 – 7), a methodological overview is presented in Chapter 3 of some of the

key issues that impact upon the methodological choices made in the course of the research.

The chapter also describes the ethical and methodological challenges that were identified by a

pilot study, and how these issues were resolved.

Chapter 4

Chapter 4 presents a small survey that was conducted to contextualise the research by

investigating the extent to which EAP teachers in Higher Education programmes in the UK

explicitly teach/correct English article use.

12

Chapter 5

The first main corpus-based study presented is a longitudinal study of the effect of explicit

teaching on 25 (L1 Mandarin Chinese) English learners during a 15-week Presessional

programme. The relative effects of correcting English article errors, teaching the article system

or not making any mention of articles will be compared and contrasted.

Chapter 6

Combining the data collected for the preceding study with some essays from lower proficiency

learners and case study responses, a corpus of 50,319 words was analysed for comparison with

a smaller corpus of L1 essays on the same topic. A comparison is then made between the essays

and a mini-corpus of case-studies in order to investigate genre effects on accuracy. In addition

to deductive analysis using the analytical framework developed by Bickerton (1981), some

qualitative methods and a freer/simpler corpus-driven inductive analysis of the same data are

conducted to investigate further the possible causes of errors.

Chapter 7

The final study uses a grammatical judgement multiple-choice methodology (455 participants)

to investigate several hypotheses formed as to why Chinese students oversupply or omit articles

and this chapter further investigates the link between the students’ general proficiency

development and their typical article use errors.

Chapter 8 (Conclusion)

After summarising and critically evaluating some of the findings in the four studies presented,

the final chapter provides some practical suggestions for EAP teachers wishing to focus on this

area of language. In addition to many concrete recommendations, it is hoped that several of

13

the main findings can help inform teachers’ ‘working hypotheses’ as to why students make

errors in article use and how students can be helped to improve their article accuracy.

14

15

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The many variables which can affect Chinese L1 learners’ accuracy in any grammatical choice

are as wide ranging and complex as the English article system itself. The first section of this

chapter shows how the grammaticalisation of definiteness in the English language has led to

an extremely complex system that does not have a simple one-to-one mapping of form and

meaning. A contrastive analysis of Chinese is then presented in order to build hypotheses about

the predicted errors in later chapters. In addition to a greater understanding of the many

variables affecting article accuracy, the review of the literature presented here highlights many

areas of uncertainty that will be addressed in the Research Questions summarised in the final

section. More generally, the last part of this chapter aims to evaluate the arguments introduced

as to whether accuracy of English articles in academic writing should and could be an

appropriate focus of attention in the teaching of English for Academic Purposes.

2.1 Key term definitions

Ø article

Throughout this thesis, reference will be made to the, a/an, and Ø (zero) articles. In the

terminology employed in some of the published literature (Langendoen, 1970; Chesterman,

1991), the ‘null’ article (sometimes termed Ø2) refers to the zero article found with singular

nouns/proper nouns) as opposed to Ø used for plural/common nouns. However, to avoid

confusion, this thesis will define all contexts in which a noun phrase can be used alone (bare)

without an article or other determiner as a Ø article context. For the sake of simplicity the

thesis therefore does not distinguish between Ø article usage with proper nouns, singular, plural

or mass nouns.

16

Omission/overspecification

Based on Dulay, Burt & Krashen’s surface taxonomy (1982), most studies use the term

‘omission’ to denote a missing article in an obligatory context (Chuang & Nesi, 2006; Díez-

Bedmar & Papp, 2008; Lee & Chen 2009; Crosthwaite, 2016a, 2017). However the terms

‘overinclusion’ (Chuang & Nesi, 2006), ‘redundancy’ of article use (ibid.), ‘overspecification’

(Lee & Chen, 2009), ‘oversuppliance’ (ibid.) and ‘oversupply’ (Crosthwaite, 2016a) are among

the many different terms used in the literature to describe article use when such use is

ungrammatical/inappropriate. This study will use the nouns ‘overspecification’ and

‘oversuppliance’ and the verb forms ‘overspecify’ and ‘oversupply’ to denote inappropriate

use (when considered an error). When use of article is unnecessary but does not affect

grammatical accuracy or appropriacy, the word ‘redundancy’ is used to denote a more broad

connotation of marked use. To illustrate, the definite article in the following example taken

from a conclusion in the corpus of essays analysed in Chapter 6 shows a noun phrase (the

managers) which was agreed as correct, if marked, by three L1 English tutors. The three tutors

agreed that Ø was more likely, but that the was permissible in context of the parallel structure:

Motivation is not the only way to incentivise people in practice, since the managers just

search for the best ways in every situation [M_09552-4-Wk1]

Underuse/overuse

In contrast with omission (and its connotation of grammatical accuracy), ‘underuse’ is used in

this thesis to denote a lower than expected frequency used when compared to L1 discourse on

the same prompt or genre. Overuse is the parallel term used for quantitatively more frequent

use in a text as a whole, whether or not such use is grammatically correct.

17

2.2 The English article system

Although many Indo-European languages have some form of article system, their ancestors

(such as classical Latin and Sanskrit) did not. Today, many other world languages (Japanese,

Hindi, Chinese) do not have an article system, even if they have other markers of definiteness.

It is generally accepted that while all languages can refer to the specificity, definiteness and

number of a noun referent in some fashion, some languages have articles [+Article] while

others are article less [-Article]. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED Online, 2010), in its 23

main entries for the use of the definite article, reported that the in its current form was first seen

in the East Midlands dialect in c 1150, firmly establishing itself in English by the time of

Chaucer. Since then it can be seen from the OED that the use of the definite article has been in

a constant state of flux. In the 17

th

century all dates were preceded by the (e.g. the 1685) and

languages were always prefixed by the (i.e. the Latin), indeed the OED cites Webster in 1934

stating that ‘The modern descendants of the Latin are called the Romance languages’.

According to most sources (Bybee, Perkins & Pagliuca, 1998) it is agreed that the definite

article originated from the Old English demonstrative that (Old English did not have an article

system) while the indefinite article a/an came from the numeral one.

2.2.1 Bickerton’s four ‘Types’ of article use

Whether or not the English article system is today used uniformly by its different users, any

framework that explains its functions and forms needs to incorporate both its pragmatic and

grammatical functions. Grammatically, the form of article will in some cases depend on the

noun’s countability and number. Pragmatically, in its referential uses, articles reflect both the

context (whether the reader can infer its definiteness or indefiniteness) and the construal of

context (whether the reader can be expected to know about the referent and whether it is to be

construed in a specific or general way). Bickerton’s Framework, as shown in Table 1 below,

18

acknowledges that article choice is determined by the discourse features of the referents,

namely whether construed by the user as a specific referent [± SR] and whether known [± HK]

to the hearer. This framework provides four ‘Types’ of English article use and has the

advantage of explaining both definite, indefinite and generic uses of articles (but not idiomatic

or proper noun uses). The next section outlines each of these in turn.

Table 1: Bickerton’s (1981) semantic and pragmatic Framework

Type

Features

Context

Form of

Article

Examples

1

1

[-SR, +HK]

Generic: The reader knows of

its existence, but not a specific

reference.

a/an

Ø

The

An elephant never forgets.

Elephants never forget.

The elephant never forgets.

2

[+SR, +HK]

Writer and reader both know of

the specific referent.

The

Remember to feed the

elephant!

That’s the biggest elephant I’ve

ever seen.

3

[+SR, -HK]

The writer knows of a specific

referent the reader does not

know.

a/an

Ø

The local zoo has an elephant.

The local zoo has elephants.

4

[-SR, -HK]

Neither writer nor reader

believe the noun refers to a

specific thing

a/an

Ø

The zoo does not have an

elephant.

The zoo does not have

elephants.

1

Examples taken from Langendoen (1970), Cziko (1986), Heubner (1983), and Butler (2002).

19

Type 1 [-SR, +HK] Generic

The Type 1 (Generic) function of the English article system is used to indicate the more

general nature of the noun as a class. This generic function is often equally served by plurals,

a/an or the, as an example from Langendoen (1970) illustrates:

i. An elephant never forgets

ii. The elephant never forgets

iii. Elephants never forget

Although generic article use is one of the rarer forms of article use generally, it is far more

common in written academic English than other forms of discourse due to its use in defining

terms and topics. Indeed, Master posited some evidence (1987: 184) that generic the is most

common in essay paragraph topic statements, supporting the assumption that paragraphs

normally start with a core generalisation since, ‘topic sentences are by definition more

generalised than other sentences in the paragraph’. After analysing a corpus of articles from

the journal Scientific American, Master (1987) reported that the Ø article was the most frequent

generic article form (54%) of all generic uses, followed by generic the (38%) and finally the

generic a/an article (8%).

The importance of generic reference in academic writing is thus clear. However, an added

complication in generic noun phrases for L2 learners of English is that, as shown in Krifka and

Gerstner’s (1987) examples in Figure 1 below, generic contexts can allow various morphemes

(including Ø). That is to say that most generic phrases can be formulated in a variety of ways

with an article or Ø with plural count nouns (sentences 1, 2, 3 and 5), often with a choice of

bare plural or singular definite with little or no change in meaning.

20

1. The lion is a ferocious beast. (singular definite generic NP)

2. A lion is a ferocious beast. (singular indefinite generic NP)

3. Lions are ferocious beasts. (generic bare plurals)

4. Gold is a precious metal. (generic bare singular)

5. One cat, namely the lion, is a ferocious beast. Some cats, namely the lion and the tiger,

are ferocious beasts. (taxonomic NPs)

6. Rice was introduced in East Africa some centuries ago. (generic bare mass noun)

Figure 1: Examples of generic NPs in all forms (Krifka & Gerstner, 1987)

Mass nouns generally only allow the limited Ø article choice (sentence 6) but, apart from this

simple observation, the bewildering choice and the complicated rules of whether bare plurals

(Lions are dangerous), definite singulars (The lion is dangerous), or indefinite singulars (A

lion is dangerous) are preferred or restricted are highly complex issues (Langendoen, 1970;

Huebner, 1983; Cziko, 1986; Butler, 2002; Yang & Ionin, 2008; Ionin et al., 2011). To some

extent this complexity will clearly prove a challenge to all L2 learners of English, but section

2.3.1 will discuss claims that Chinese L1 learners may have particular issues with this type of

use.

Type 2 [+SR, +HK] Definite Articles

The definite article is the one type of article that can (and must) take only one morpheme as its

article: the. To be definite the referent must not only be specific, but must be construed as

‘known’ to the hearer. Being ‘known’ means it could be previously known or implied in an

inference to be made known through an utterance, or as Verspoor (2008) explains, ‘those

entities that are not necessarily identifiable to both the speaker and hearer, but the hearer can

infer that the speaker refers to a unique one in his mind as in “Be aware of the dog”, “I went

21

to the park”, or “I took the bus”’. As Berry points out (1991: 254), in such cases the definite

article ‘notifies the reader of the future significance of the referent’.

The definite article is also important in academic English because, although much of academic

writing at university relates to general ideas (and generic noun phrases), many of these ideas

will be supported by reference to specific examples. Moreover, the language of an academic

paper will be quasi-specific due to intra and inter-textual references; anaphoric (second

mention) reference; reference to the literature in the field; and cataphoric reference among other

functions. Quirk & Crystal (1985) identify eight functions of the definite article in writing:

as a marker of specific reference: the immediate situation (the roses are beautiful); unique

reference (the sun/the moon); anaphoric reference (second mention); cataphoric reference

(post-modified noun phrases and ‘of’phrases); sporadic reference (my sister goes to the theatre

every month); logical use with adjectives (the same, the only, superlatives) and reference to

body parts (the mind). Six of these functions of the definite article, setting sporadic reference

and body parts aside, seem most important for academic writing. Of these six written functions,

evidence suggests moreover that it is cataphoric reference which learners will most need in

academic English since, according to Biber et al. (1999), 40% of definite articles used in

academic writing have this function.

Type 3 [+SR, -HK] Indefinite articles

Where the reader cannot be assumed to have knowledge of the reference (for instance first

mention), a specific referent will be determined by a/an if a singular count noun, or Ø if

referring to a mass noun or plural count noun. Again, their use in academic English will be

related to specific examples used to support the more general claims in academic writing.

Type 4 [-SR, -HK] Non-referential noun phrases

22

When neither writer nor reader believe the noun refers to a specific thing, there is again the

same choice of morpheme: a/an for singular count nouns and Ø for non-count or plural. Further

examples from Ekiert (2004) are listed in Figure 2 overleaf. Such non-referential noun phrases

are likely to dominate much of academic writing, particularly when the genre requires general

claims, an evaluation of different (unreal) scenarios, conditional clauses and possible unproved

hypotheses.

Alice is an accountant.

I guess I should buy a new car.

Ø Foreigners would come up with a better solution.

Figure 2: Further examples of non-referential noun phrases from Ekiert (2004)

2.2.2 The conventional use of articles

Following Liu & Gleason (2002) and Ekiert (2004), this thesis will classify all uses of articles

that fall outside the Bickerton Framework, as ‘conventional use’, in that they are not a matter

of choice and do not follow immediately evident contextual considerations. This includes

idiomatic uses and proper nouns that are often taught to students as ‘things you just need to

learn’. This is not to say that such uses were not historically motivated. In fact, many uses of

proper nouns can be seen as logical (the definite article is normally only used when the proper

noun combines with a common noun). However, many uses would be difficult to explain

without in-depth research of the historical roots of the linguistic motivation.

Many discourse markers in academic English (e.g. the first point, on the other hand) could be

argued to fit into what Quirk & Crystal (1985) term ‘logical uses’ of definite article. However,

it might be more difficult to explain the majority of discourse idioms (e.g. on the whole, on the

23

rise, in the main). Even greater confusion is moreover caused by proper nouns, which normally

take Ø article (e.g. France, Mont Blanc, Peugeot, Tower Bridge) but sometimes take a definite

article (e.g. the UK, the Alps, the Seine, the Tower of London). This confusion may affect

[+Article] students as well as [-Article] learners because these conventions are so different (for

example the French would say ‘la France’ in addition to ‘le Royaume Uni’, adding a definite

article regardless of whether a country is singular, plural, a group of islands or a kingdom).

In summary, the grammaticalisation of the article system in English has led to an extremely

complex range of choices for the English L2 learner that may impact upon their writing style

and quality in academic English. Regardless of L1 background, the main problem facing all

learners is first and foremost that the article forms do not have simple form to function patterns

of use (Butler, 2002) and various forms of article have duplicated uses in different functions.

Furthermore, the learner needs to know the characteristics of the head noun before making their

choice. For Type 1 and Type 3 contexts, the choice of article often requires a knowledge of

the head noun’s singular/plural and count/mass-noun characteristics. Type 1 (generic) contexts

sometimes allow a choice of article (Ø with a plural or mass noun or a/the with a singular) but

in other cases require more restricted use. Finally, there are conventional uses that require a

knowledge of the original motivation for using the article (which may be obscured in the

present form). In sum, unlike many aspects of grammar that have a clear form/function

relationship, L2 English learners are facing a range of choices that have lesser or greater

restrictions in different contexts.

2.2.3 Evaluation of the effect of article errors

Article errors are often invisible and may be often considered less relevant in spoken English.

However, there seems a convincing argument that learners who wish to write academically or

professionally require more accurate use of articles (Master, 1987). There are two main

24

problems often caused for students who make many article errors. Firstly, the reading audience

may negatively perceive their message, equating their grammatical accuracy with their subject

knowledge (Master, 1995). Secondly, although the majority of errors are superficial – causing

only annoyance rather than confusion – some article errors can cause a barrier to effective

communication. The following example is taken from a student’s assignment in which she

first used (1) but later saw that she was meant to use (2) after teacher feedback.

The WTO has developed a high level of influence and consequently has had a large impact on

(1) …the number of trade-related issues …

(2) ...a number of trade-related issues….

(unpublished – author’s student)

In another published example Berry (1991) illustrates how article choices can have an effect

on the readers’ understanding:

(3) I want to know the English.

(4) I want to know English.

A further example from Berry shows how the article error can have a more nuanced but

nonetheless important effect on the readers’ construal of the message:

(5) Police investigating the crime have discovered a gun.

(6) Police investigating the crime have discovered the gun. (i.e. the one used

in the crime)

It could be counter-argued that the vast majority of article errors have a negligible effect on

communication, being only superficial or what are sometimes called ‘local errors’ (Burt &

Kiparsky, 1974) which seldom lead to miscomprehension. There are certainly academic

English competencies that should take a higher priority in the EAP teaching curriculum at all

25

learning levels and a high emphasis on all elements of the rule based article system in the most

intense courses or lower level classes will not be recommended at any point in this thesis. On

the other hand, when time permits incidental attention to this area, the neglect of the most

frequently occurring word in the English language seems less reasonable. This attention seems

particularly important in the context of international students paying high fees in university

Presessional EAP courses to learn how to avoid any misunderstandings of any sort in their

writing. Regardless of world English arguments, with their eyes set on the submission of

academic assessments, most international students expect EAP tutors at university to provide

scaffolded support towards accurate and genre appropriate writing skills.

Clearly, given that students frequently set themselves unrealistic and unnecessary goals such

as ‘native-like accuracy’, part of an effective EAP tutor’s role is to make students understand

that the occasional slip or marked overuse of articles will not prevent them achieving their

goals. The frequent overcorrection of article use that shall be demonstrated in this thesis is

likely to represent a recognition of such demands without adjustment of expectations, however

unhelpful such practices are shown to be. Equally, however, given the financial/time

investment these students have made in a presessional programme, it would seem disingenuous

to pretend that excessively inaccurate use of determiners in a piece of academic writing will

not have any effect at all on the reader. At some point in the learners’ proficiency, the neglect

of the article system in the syllabus becomes more difficult to defend. It may be more related

to the complexity of the grammar itself, teachers’ concerns about discouraging learner

motivation or a gap in available resources for the effective teaching of this language area.

On the one hand, difficulties with articles may be experienced by all learners of English,

regardless of L1 background. On the other hand, it has often been assumed that differences in

the way L1 languages express definiteness may have crosslinguistic interference on their

26

learning of the article system in English. The background to this assumption is explored in the

next section.

2.3 Contrastive Analysis

The claim has historically been made, both strongly (Lado, 1957) and in more nuanced forms

(Gilquin, 2008), that L1 background contributes to language inaccuracy in some way (the

Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis). A hypothesis has thus been made (Díez-Bedmar & Papp,

2008) that students will be more challenged by article use if their first language does not 1)

grammaticalise the article system at all or 2) grammaticalises the system in a different way.

This thesis will investigate a weak form of the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis, but it will not

make the simplistic uncritical assumptions of linguists from the Contrastive Analysis era (e.g.

Lado, 1957) in which L1 negative transfer effect was thought to be the dominant if not singular

determiner of error. On the other hand, it will not take the equally extreme assumption of the

dominant SLA theories of the 1970s-1980s which perhaps underestimated crosslinguistic L1

interference.

Indeed, in the 1970s the widespread rejection of all forms of the CA hypothesis in both the

SLA and teacher training fields would have made this thesis impossible to write. Fortunately,

this thesis is written in an era of less doctrine and greater plurality of linguistic assumptions.

Cognitive linguistics in particular has been responsible for ‘reopening’ the issue of

crosslinguistic interference (Langacker, 1986). Figuratively speaking, applied linguists today

are more unshackled in their assumptions and can investigate all the possible determiners of

L2 development. This has given opportunities for a diversity of new approaches including

learner corpus-based integrated contrastive analysis approaches (Granger, 1996). Meanwhile,

the affordances of modern technology, combined with an acceptance of a range of factors

affecting L2 development have allowed the empirical examination of learner data (Ellis &

27

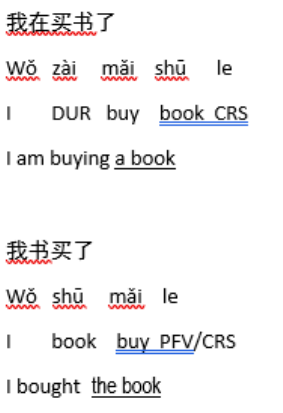

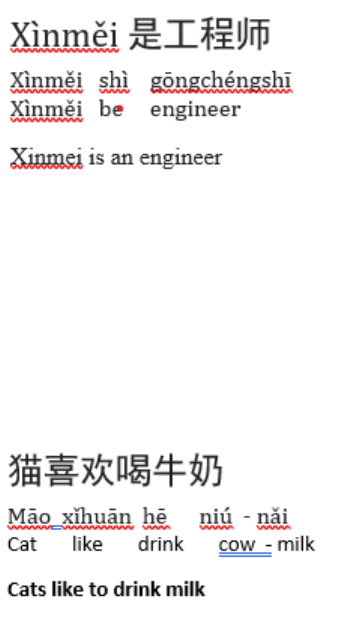

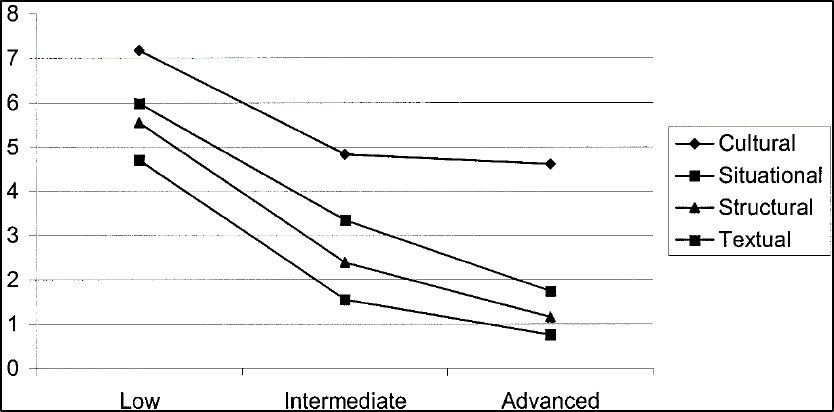

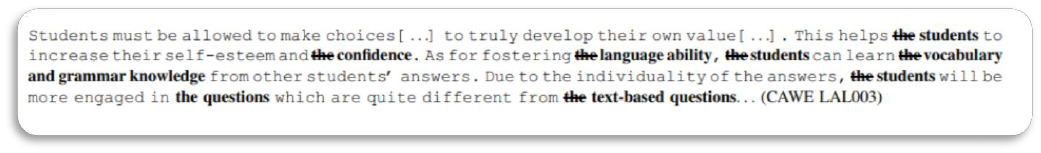

Larsen-Freeman, 2009) with a renewed focus on L1 transfer effects in general (Gilquin, 2008)