Landmarks Preservation Commission

May 17. 2005, Designation List 363

LP-2176

SUMMIT HOTEL (now Doubletree Metropolitan Hotel), 569-573 Lexington Avenue (aka 132-166 East 51

st

Street), Manhattan. Built 1959-61; Morris Lapidus, Harle & Liebman, architects.

Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map, Block 1305, Lot 50.

On March 29, 2005 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed

designation as a Landmark of the Summit Hotel (now Doubletree Metropolitan Hotel) and the related Landmark site

(Item No. 2). The hearing had been advertised in accordance with provisions of law. At this time, the owner testified,

taking no position on designation. Twelve witnesses spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the

Landmarks Conservancy, Historic Districts Council, Docomomo-US, Friends of the Upper East Side, Modern

Architecture Working Group, Landmark West, and the Municipal Art Society. The Commission also received numerous

letters and e-mails in support of designation. The hearing was continued on April 21, 2005 (Item No. 4). Three

witnesses testified in support of designation, including representatives of the Modern Architecture Working Group and

Docomomo-US. At this time, a representative of the owner testified, taking no position.

Summary

Admired for its unusual shape, color, and stainless steel sign,

the Summit Hotel is an important work by Morris Lapidus.

Begun in 1959, it was the first hotel built in Manhattan in

three decades and the architect’s first hotel in New York City.

Lapidus was especially proud of this building and reproduced

an image of the Summit on the cover of his autobiography,

The Architecture of Joy

, published in 1979. Trained at

Columbia University, he enjoyed considerable success as a

retail designer in the 1930s. After the Second World War,

Lapidus began to design hotels, including the celebrated

Fontainbleau and Eden Roc in Miami Beach. These

accomplishments led to his association with the Tisch family,

who commissioned the Americana Hotel in Bal Harbour,

Florida, in 1956. After acquiring a controlling interest in

Loew’s Theaters, they commissioned the Summit, which

adapts many of the devices Lapidus perfected in Florida to a

challenging, constricted site at the corner of Lexington

Avenue and East 51

st

Street. Built in reinforced concrete, a

material favored for its sculptural potential, the curving north

and south elevations are clad in light green glazed brick and

dark green mosaic tile manufactured in Italy. The top three

stories, built as penthouse suites, are faced in green structural

glass. To further distinguish the building from its neighbors,

the door handles were inlaid with colorful mosaics and the

base along East 51

st

Street is illuminated by globe-shaped

lighting fixtures. On Lexington Avenue, he designed a

striking illuminated sign. Consisting of seven disks hung

between stainless steel pins, this unique element enhanced the hotel’s street presence, making it visible from a

distance. Other distinctive features include a pair of neon signs that direct drivers to the parking garage and a

stainless steel ash tray that serves cigarette smokers descending into the subway. The hotel opened in August

1961, generating considerable media attention. Some writers greeted the new hotel with disappointment or

amusement, while others viewed it as a disharmonious addition to the streetscape. In subsequent years, however,

the hotel attracted an increasing number of admirers and aside from alterations to the Lexington Avenue entrance,

this flamboyant modern structure retains much of its original character.

2

DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS

Morris Lapidus (1902-2000)

1

The Summit Hotel was designed by Morris Lapidus, one of the most influential hotel

designers of the 20

th

century. Born in Odessa, Russia, in 1902, he and his family immigrated to the

United States in 1903. They lived on the Lower East Side for several years, moving to Williamsburg,

and later, to the East New York section of Brooklyn. Lapidus attended Boys High School (a

designated New York City Landmark) in the Bedford section, and for a brief time trained as an actor

at New York University. During the mid-1920s, he attended architecture school at Columbia

University, studying with Frederic C. Hirons and Wallace K. Harrison. Lapidus worked as a

draftsman for several firms, including Warren & Wetmore, Bloch & Hesse, Arthur Weiser, and for

fifteen years, Evan Frankel (of Ross-Frankel). In the office of Ross-Frankel, during the 1930s, or

working independently, he designed or supervised the construction of more the five hundred

storefronts, shop interiors, and showrooms.

Lapidus formed his own office in 1943 and gradually began to design entire structures,

including stores, synagogues, apartment buildings, and an estimated two hundred hotels. Early works

by Lapidus in New York City include: L Motors (1948, demolished) in Washington Heights, Shaare

Zion synagogue (1954) in Flatbush, and the America Fore Insurance Group Office Building (1960) in

downtown Brooklyn. A retail designer at heart, he created extravagant works that challenged the

minimalist trends of the 1950s. He often worked in broad strokes, juxtaposing modern and traditional

forms, as well as color, texture, and light. Lapidus eschewed right angles, creating structures that had

unusual floor plans and distinctive shapes. His best-known commissions are located in southern

Florida, namely the crowd-pleasing Fontainbleau (1954) and Eden Roc (1955) hotels, on adjoining

parcels in Miami Beach. Lapidus later observed that the plan of the Fontainbleau “resembles nothing

from the past. There’s hardly a straight line in it – it just moves, one curve going one way, and another

in the opposite direction. There’s no end.”

2

Lapidus designed the Summit Hotel in association with Harle & Liebman. Leo Kornblath,

who is listed as a partner in filings with the Department of Buildings, is not identified on the building

plans and established his own firm during the hotel’s construction.

3

During these years, Lapidus

operated two offices: in Manhattan, on East 56

th

Street; and in Miami Beach, on Lincoln Road. Harle

& Liebman are identified as interior designers, with offices in New York City and Miami Beach.

Lapidus met Abby Harle (born Hornstein) in 1945 and they worked together until the mid-1960s.

Harold Liebman joined the New York office in the late 1950s, principally to design apartment houses

and remained until the mid-1960s.

Lapidus closed his Miami office in 1984, but lived long enough – 98 years – to be recognized

as an American original. He was credited as being a “postmodernist long before the term existed” and

even Philip Johnson praised his unabashedly flamboyant work, calling him the “father of us all.”

4

Hotels in New York City

Since the opening of Astor House (1831, demolished), opposite City Hall, structures built to

provide temporary accommodations have earned an important place in the Manhattan cityscape. At

their highest level, hotels symbolize what the city aspires to be – a place of fashion, fantasy,

convenience, and comfort. Among prominent architects to design hotels, three firms stand out: Henry

J. Hardenbergh, Schulze & Weaver, and Lapidus. Active in distinct and successive eras, their best

designs capture the spirit and taste of their generation. Hardenbergh, author of the hotel entry in the

Dictionary of Architecture and Building

(1902), edited by Russell Sturgis, was architect of the original

Waldorf-Astoria Hotel (1893-96, demolished 1930), the Martinque Hotel (1897-1911, a designated

New York City Landmark), and the Plaza Hotel (1907, a designated New York City Landmark) in

New York City, as well as the Willard Hotel (1906) in Washington, D. C., and the Copley Plaza

(1912) in Boston. Built in variants of the classical style, these buildings defined the modern hotel,

establishing standards of appearance and plan. Schulze & Weaver were the leading firm in the 1920s

and 1930s, designing the Sherry-Netherland Hotel (with Buchman & Kahn, 1927, part of the Upper

East Side Historic District), the Hotel Pierre (1928, part of the Upper East Side Historic District), and

3

the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel (1929-31, a designated New York City Landmark). They also designed the

Sevilla Biltmore Hotel (1921) in Havana, Cuba, the Biltmore (1923) in Los Angeles, and the Miami-

Biltmore Hotel (1926) in Coral Gables, Florida.

No hotels were built in Manhattan during the 1950s. Despite great success in Florida, in his

home town Lapidus remained, for the most part, an interior designer. Initial hotel projects involved

remodeling earlier structures, such as the lobby of the Hotel Governor Clinton (1957) at Seventh

Avenue and 31

st

Street and various interiors in the Hotel New Yorker (1959-60) on Eighth Avenue,

between 34

th

and 35

th

Streets. Outside New York City, however, he designed a considerable number of

hotels and resorts, such as the Hollywood Hotel (1952) in Long Branch, New Jersey, the Surf Club

Hotel (1954) in Atlantic Beach, New Jersey, Kutsher’s Country Club (1955) in Monticello, New

York, and the Concord Hotel (1958) in Kiamesha Lake, New York.

The Developer

5

Lapidus began his association with the Tisch family in 1947. Al Tisch manufactured clothes

and ran two children’s camps in the Poconos. At the urging of his older son Laurence Tisch, who

graduated from the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce in 1943, these businesses were sold in

1946 and the revenue invested in Laurel-in-the-Pines, an aging 300-room-resort in Lakewood, New

Jersey. Laurence’s brother, Robert Preston Tisch, joined the firm in 1948. Though Lapidus described

the role he played as “minor,” this initial project established a professional relationship, helping him to

eventually secure the opportunity to design the $17 million Americana Hotel in Bal Harbour, Florida.

6

Completed in 1956, this commission led to a profile of the architect in the

New York Times

that

described the five-hundred room hotel as “the brightest jewel in the Tisch family’s crown of resort

hotels.”

7

The first hotel that they operated in New York City was the McAlpin (1913), acquired in

1951.

8

Nine years later, Tisch Hotels, Inc. acquired a controlling interest in Loew’s Theaters, Inc.

Hurt by anti-trust judgments, the movie theater industry was struggling and they may have acquired

the company for its plentiful real estate holdings. At this time, Laurence Tisch moved his family from

Florida to the New York suburbs. He appointed himself chairman of the board and Preston Robert

Tisch served as chairman of the executive committee.

The first project announced by Loew’s Hotels was the Summit, initially called the Americana

of New York or the Americana East. In subsequent years, the company would be involved with at

least eight Manhattan hotels, including three properties designed by Lapidus: the Loew’s Motor Inn

(1961) on Eighth Avenue, between West 48

th

and 49

th

Streets, the Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge

(1962) on Eighth Avenue, between West 51

st

and 52

nd

Streets, and the Americana Hotel (now called

the Sheraton Centre, 1960-62) at 811 Seventh Avenue, between West 52

nd

and 53

rd

Streets. The last

hotel was the largest of the group. Faced in marble and yellow brick, the V-shaped slab contained two

thousand rooms.

The Summit was built on the site of Loew’s Lexington Avenue Theater.

9

Built by Oscar

Hammerstein as an opera house in 1913, it was soon acquired by Marcus Loew who used the spacious

auditorium to present vaudeville shows, and later, films. The entrance was located on Lexington

Avenue but the theater itself was located mid-block, between Lexington and Third Avenue. North of

the entrance, at the corner of 51

st

Street was a single-story retail structure, measuring fifty by one

hundred feet. Demolition of both buildings began in 1959.

The area north of Grand Central Terminal was ideal for a new hotel. Many had been erected

here during the 1920s, particularly along Lexington Avenue, where, from south to north, the

Lexington (1928-29), Shelton (1924), Belmont Plaza (originally the Montclair, 1928), Barclay (1927),

Waldorf-Astoria (1931, a designated New York City Landmark), and Beverly (1927) were found.

These hotels catered to travelers and people attending events at the Grand Central Palace (1913,

demolished), a convention hall. This activity increased during the 1950s; in addition to the completion

of the United Nations Headquarters and the demolition of the Third Avenue el, one block away Park

Avenue was fast becoming the city’s most prestigious business address.

4

Construction

Plans were filed with the Department of Buildings in early 1960 (NB 59-60) and ground was

broken in June 1960.

10

The structural engineer was Farkas & Barton, and the Diesel Construction

Company was general contractor, with Dic Concrete Corporation as subcontractor for the concrete

frame.

The Summit Hotel has a structural frame of reinforced concrete – the first hotel in New York

City to adopt this technique. Lapidus recalled: “All of my construction . . . was of concrete and I had

no desire to use steel.”

11

American architects first began to exploit this material’s sculptural potential

in the 1940s and 1950s. Several unconventional structures were planned or under construction in New

York City: the Guggenheim Museum (1956-59, a designated New York City Landmark and Interior),

Begrisch Hall (1956-61, a designated New York City Landmark) at New York University’s University

Heights Campus in the Bronx, and the TWA Flight Center (1956-62, a designated New York City

Landmark and Interior) at Kennedy Airport. Plans for Chatham Green (1956-61), a 21-story middle-

income cooperative apartment building near Chinatown, were filed in 1959.

12

It, too, had an S-shaped

plan, suggesting that unusual forms and footprints were becoming mainstream.

Concrete also had significant economic benefits. Not only was it faster to construct than a

steel-framed structure, but the engineers reported that the Summit progressed “at the fastest rate ever

achieved for a reinforced concrete building.”

13

Beamless construction was also more efficient,

permitting slightly higher ceilings and greater flexibility in layout. Furthermore, by bending the floor

plan, Lapidus said he was able to produce a building of greater length, and therefore – more rooms. He

wrote: “A straight line, I reasoned, is the shortest distance between two points . . . Why not bend the

hall, in other words, create a squiggle or an S-shaped building with an S-shaped hall. Why not? . . .

My clients were happy.”

14

The Design

Shape and color are the Summit’s most distinctive characteristics. Many writers, including

the architect, have called the shape an S-curve, while others have referred to it as a “serpentine slab”

or an “undulating serpentine.”

15

Above the base, the hotel stands free on three sides, adjoining only

the windowless brick façade of the 13-story Girl Scouts Building (1957-58) to the east, at 830 Third

Avenue. This arrangement enhanced the Summit’s sculptural character, while providing views from

every room.

Lapidus justified the unusual shape in economic terms, but he was also inspired by early

developments in European modernism, particularly the work of the German architect Erich

Mendelssohn, who he described as his teacher. During the late 1920s, Mendelssohn designed several

well-publicized commercial buildings in Germany. Lapidus wrote: “I found in his work a tremendous

desire to break loose from cubistic and rectangular buildings. His sweeping, curving undulating

buildings excited me, and he had a profound influence on my career.”

16

Somewhat more surprising

was his debt to Mies van der Rohe. Two early residences by the architect, the Lange House (1928) and

Tugenhadt House (1930), incorporate curving interior walls. Lapidus said: “I am sorry to say, that

after this, he never sinned again, and so I began to use sweeping curves and S curves, and all sorts of

odd-shaped spaces.”

17

Comparisons can also be made to a work by the lesser-known Luckhardt

Brothers, architects of Telschow House (1928, demolished), a five-story office building on

Potsdammer Platz in Berlin that was distinguished by an undulating façade and setback tower. The

Summit also recalls Baker House (1947-49), a brick-faced dormitory at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology in Cambridge, designed by Alvar Aalto.

Lapidus also acknowledged Brazilian sources. He traveled to South America and visited

Oscar Niemeyer in 1949. “He had a great influence . . . he was a man who was doing things the way I

thought they should be done,” Lapidus later commented.

18

Both architects favored sinuous curving

forms. In 1953-54, Niemeyer’s Copan Building was completed in the center of Sao Paulo, a

monumental mixed-use structure with a 40-story undulating façade. Lapidus may have also been

familiar with the Pedregulho Apartments outside Rio de Janeiro, designed by Affonso Reidy.

Completed in 1952, the 260-meter-long serpentine complex was featured in

Recent Architecture in

Latin America

, published by the Museum of Modern Art in 1955.

5

Use of Color

Color played an important role in Lapidus’ career, in his retail work and hotels. In a 1961

interview he asserted there was far too little of it in New York City. For the Summit, green is the

dominant color. The main elevations juxtapose rectangles of light green brick and dark green mosaic

tile. The East 51

st

Street storefronts and penthouse levels incorporate green structural glass and the

pre-cast concrete panels that line the sidewalk are separated by strips of green mosaic tile.

Lapidus began his career in the late 1920s, a period when terra cotta and glass were available

in an increasing range of colors. Raymond Hood, who predicted in 1927 that one day the city would

be filled with “gayly colored buildings” was the designer of the McGraw-Hill Building (1930-31, a

designated New York City Landmark), a 37-story tower wrapped in turquoise terra cotta.

19

Lapidus

credited his influence, praising Hood’s use of “fresh blue and green.”

20

After the Second World War,

tinted glass gained popularity. The United Nations Secretariat (1952), the first of many glazed curtain

wall skyscrapers, had two five-hundred-foot-tall facades of green transparent glass. Other significant

examples include Lever House (1950-52, a designated New York City Landmark), the Seagram

Building (1955-58, a designated New York City Landmark), and the Spring Mills Building (1962).

Directly across from the hotel stood the Grolier Building (1957-58, altered) at 575 Lexington

Avenue. Faced in anodized aluminum panels, the 34-story structure had what was described as a

“gleaming gold” skin.

21

A similar solution was adopted for the Administration Building of the Fashion

Institute of Technology on West 27

th

Street in 1956-59. Designed by De Young, Moscowitz &

Rosenberg, the faceted façade features brown aluminum panels and gold-framed windows.

22

Also of

note was Wallace Harrison’s Caspary Auditorium (1958, altered) at Rockefeller University, originally

consisting of a single concrete dome clad in vibrant multi-colored Italian tile.

23

White marble panels originally covered the windowless Lexington Avenue facade. It had a

rich constellation of green marble veins, complementing the colors used on the north and south

elevations. It recalls the arrangement at the United Nations Secretariat, which also juxtaposes white

marble and green glass. Photographs suggest that the marble chosen was quite rich in appearance but

it quickly began to deteriorate and was soon replaced by beige-colored aluminum panels.

The Sign

The absence of windows on Lexington Avenue highlights the hotel’s remarkable stainless

steel sign. It consists of seven oval illuminated disks, each displaying a single letter in the hotel’s

name and resting between banner-like supports. Unlike most of his colleagues, Lapidus had

considerable experience with signage, particularly in his retail work. He favored dramatic billboard-

like effects, silhouetting three-dimensional lettering against backgrounds of contrasting materials and

color. He employed this technique at the San Souci (1949), Algiers (1951), and Eden Roc (1955)

hotels.

The sign at the Summit, however, was unique in his career. Framed in stainless steel, it was

planned from the start and appears in early renderings when the hotel was called the Americana.

24

It

projects above Lexington Avenue, making the name of the hotel visible from the north, south, and

west. Early electric signs were modestly incorporated into clocks, and, in other instances, brightly

illuminated in neon, especially in buildings that were devoted to entertainment. These signs were often

positioned above the marquee to spell out the name of a theater. Rooftop signs gained popularity in

the early 20

th

century. Most had no relationship to the architect’s design and were installed for

maximum visibility. Memorable examples include: the Germania Life Insurance Company Building

(1910-11, now W Hotel) and Tudor City (late 1920s, both are designated New York City Landmarks).

A rare exception to this pattern is the McGraw Hill Building (1931, a designated New York City

Landmark) in which Hood integrated a sign of handsome 11-foot-high terra-cotta letters across both

sides of the top floor.

Lapidus designed the Summit at a time when an increasing number of commercial buildings

were identified by large illuminated signs, such as 666 Fifth Avenue (1957) and the Pan Am Building

(1963). But it is the three-dimensional quality of this sign that makes it most distinctive. This can be

interpreted as a response to roadside signage in Florida, Las Vegas, or possibly southern California,

6

but also as a gentle personal critique of the tasteful character that most modern office buildings,

especially on Park Avenue, projected. More importantly, the sign enhanced the hotel’s presence on

Lexington Avenue. The main façade is quite narrow and Lapidus turned the width of the lot to his

advantage, producing an eye-catching, three-dimensional advertisement for the hotel. In a city where

flamboyant roadside or “Googie” architecture is in short supply, the sign is one of the building’s most

distinctive features.

Entrances

The main entrance is located at the base of the Lexington Avenue façade. The original entry

sequence (now altered) began with a small plaza, paved in light-colored terrazzo. On the south side,

set behind a raised marble planter, was the El Gaucho restaurant. Set below and apart from the main

structure, the restaurant façade originally featured a “molded stone-like lattice work . . . fitted with

small pieces of stained glass.”

25

To the north was the Casa del Café, a restaurant claiming to serve

nineteen varieties of coffee. To reach the lobby, guests passed between stainless pillars, each marked

with vertical lines. From here, the underside of the tower was visible and was probably clad with

mosaics.

The entrance to the garage is located at the rear of the East 51

st

Street façade.

Accommodating drivers was perceived as an important modern convenience and beginning in 1960

most Manhattan hotels, including those designed by Lapidus, were planned with parking facilities.

Large vertical metal signs with red neon lettering identified the entrance. The

New York Times

enthusiastically reported that the arrangement at the Summit “will permit a patron to drive his

automobile into a five-story, 250-car garage and then be whisked up to a huge modernistic lobby in a

high-speed elevator.”

26

The Summit Opens

The planning and opening of the $25 million Summit Hotel was heralded as an important

event. About $300,000 was spent to promote the hotel. Strategies included chain letters, radio

commercials, and “ads flashed across movie screens.”

27

Numerous ads were placed in international

publications with an eye to attracting international visitors. A dozen languages were spoken by the

staff and the general manager was Robert Huyot, formerly of the celebrated Hotel de Crillon in Paris.

As the first hotel to open in Manhattan in thirty years, it marked the beginning a hotel

construction boom. These hotels not only filled a real need but many were built in anticipation of the

1964 World’s Fair. Originally named the Americana and the Americana East, the name Summit Hotel

is likely to have been chosen for having diplomatic associations. In the raised planter located in the

south section of the plaza were three flagpoles. At the opening ceremony, Carlos P. Romuto,

Ambassador of the Philippines, raised the flag of the United Nations, Deputy Mayor Paul Screvance,

the flag of the United States, and Robert W. Watt, of the Department of Commerce and Industry, the

flag of New York City. The top three floors were devoted to suites – Presidential, Continental,

Summit, Sunset, and Villa Este. Clad in floor-to-ceiling glass, each suite had its own terrace. The

first occupant of the Presidential suite was Groucho Marx.

28

Reception

The opening generated considerable attention from the media. The attention, however, was

not entirely flattering and in the months that followed the opening was used by writers to criticize

Lapidus and particularly the design of the interiors. He had built relatively few buildings in New York

City and the Summit provided them with the opportunity to evaluate a local architect’s work. Some

greeted the new hotel with disappointment or amusement, while others viewed it as inappropriate

addition to the midtown streetscape. These, often harsh, comments deserve attention, but often

overshadow more positive viewpoints. Olga Guelf, editor of

Interiors

, though critical of the interior

scheme, praised Lapidus, describing the overall design as “daring, capable, and relatively successful.”

In the

Nation

, Walter McQuade, who introduced the overheard and much-repeated quip that the

location was “too far from the beach” was generally positive. He called the Summit a “prime example

of the Miami Beach style” distinguished by a “deliberately diverting shape.”

Time

magazine disliked

7

the green color but viewed the serpentine curve as a “welcome change from Manhattan’s orange-crate

regularity.”

29

In September 1962, following the opening of the Americana, CBS News devoted a one-hour

television show to Lapidus and his work in Manhattan. While the editor of

Architectural Forum

, Peter

Blake, condemned the curving design, saying “Let’s not have anymore snake dances on Lexington

Avenue,” the moderator Mike Wallace asked: “Why must all buildings be square boxes and why did

they all have to be red brick or white brick? Why not use curves, why not use color.” Philip Johnson,

who at the time was beginning to doubt his long-standing allegiance to Bauhaus aesthetics and Mies

van der Rohe, refused to criticize Lapidus, saying “I, for one, will pass no judgment, but will watch

his career.”

30

Lapidus defended his design, arguing that the same people who stayed in his Florida hotels,

attacked the Summit. In later years, he grew increasingly proud of the hotel and featured it on the

book jacket of his 1979 autobiography,

An Architecture of Joy

. Lapidus clearly enjoyed controversy

and did not attempt to silence or hide his critics. When Loews began renovations in 2000, Lapidus

proudly told the

New York Times

that it has been “the most hated hotel in New York.”

31

Subsequent History

In October 1961, just three months after the opening, the lobby was remodeled.

32

These

alterations appeased critics but had no significant effect on the exteriors. The windowless Lexington

Avenue façade was refaced with aluminum panels in the 1960s. A major renovation was undertaken in

the late 1980s. At this time, the south planter and flagpoles were removed and a larger restaurant, with

a maroon-colored exterior, was introduced. The coffee shop on the north side of the main entrance

was also enlarged through the addition of a greenhouse-like pavilion. This feature has since been

removed. In 1999-2000 Michael E. Granville of Darius Toraby Architects conducted an extensive

restoration of the building. At this time, many repairs were made and missing tiles were replaced.

Michael Ferrara, director of facilities at Loews Hotels, said that he and the design team “felt strongly

about keeping the sign” and they figured out how adapt it to the hotel’s new and longer name.

33

The building was acquired by Metropolitan Hotel Realty in August 2003.

34

At this time,

there were 722 rooms. The owner undertook several significant alterations to the exterior in 2004 and

2005, approving replacement of the original steel-framed windows with thicker silver-colored

aluminum windows. This change, replacing one-over-one windows with sliding panes, alters the

façade’s rhythm. In addition, the base along East 51

st

Street (west of the storefronts) has been mostly

refaced with light green glass, covering but not destroying the original marble aggregate panels and

green mosaic tile.

At the close of his life, Lapidus was extremely proud of Summit. In a letter to the developer,

Robert Preston Tisch, sent in September 2000, he recalled his experience with candor, writing: “And

in many ways all of my talent was used to remedy a program that might have been a fiasco . . . It is a

hotel where I used every bit of talent to do something that I would always be proud of. I don’t think

that any building design change could improve what I have designed for you over 40 years ago. I

don’t think any designer could surpass in building what I did for your Summit.”

35

Description

The Summit (formerly the Loew’s New York Hotel) is now called the Doubletree

Metropolitan Hotel. It is located on a 100 by 320 foot parcel at the southeast corner of Lexington

Avenue and East 51

st

Street. The base, incorporating the lobby and storefronts, fills the entire site.

One story (plus mezzanine) tall along Lexington Avenue, the height increases as it approaches Third

Avenue. Above the base, the S-shaped slab contains fifteen stories of guest rooms, crowned by a set-

back penthouse and an irregularly-shaped mid-block mechanical tower.

The main entrance faces Lexington Avenue. It is set between two non-historic storefronts,

each occupying space that was once part of a small plaza. Along East 51

st

Street, the walls are mostly

faced in non-historic green glass squares. These panels, installed in early 2005, conceal the original

pre-cast concrete panels and strips of green mosaic tile. Globe-shaped aluminum lighting fixtures,

projecting from the mosaic tile, are located above. On the roof of the base are stainless steel planters

8

and railings. Though not currently in use, both are original to the building. A recessed service

entrance, located midway between Lexington Avenue and the mid-block storefronts, is non-historic.

Three storefronts, clad in stainless steel and clear glass, are recessed below the second story,

forming a shallow arcade. To the east, a non-historic vinyl awning and doors lead to a vestibule and

the rear of the lobby. This secondary entrance incorporates a pair of glass doors with the original bow-

tie shaped handles inlaid with colorful mosaics. The second story is divided into three bays, each

having four vertical windows, flanked above and below by dark green glass. Farther east is the

entrance to the loading dock, trimmed in the original metal. Near the east end of the building is the

entrance to the garage, crowned by the original metal louvers. The pre-cast concrete panels and strips

of green mosaic tile that surround the entrance are original, as are the two metal “PARKING” signs

that have red neon lettering and arrows. The width of these panels is similar to the width of the

windows in the penthouse.

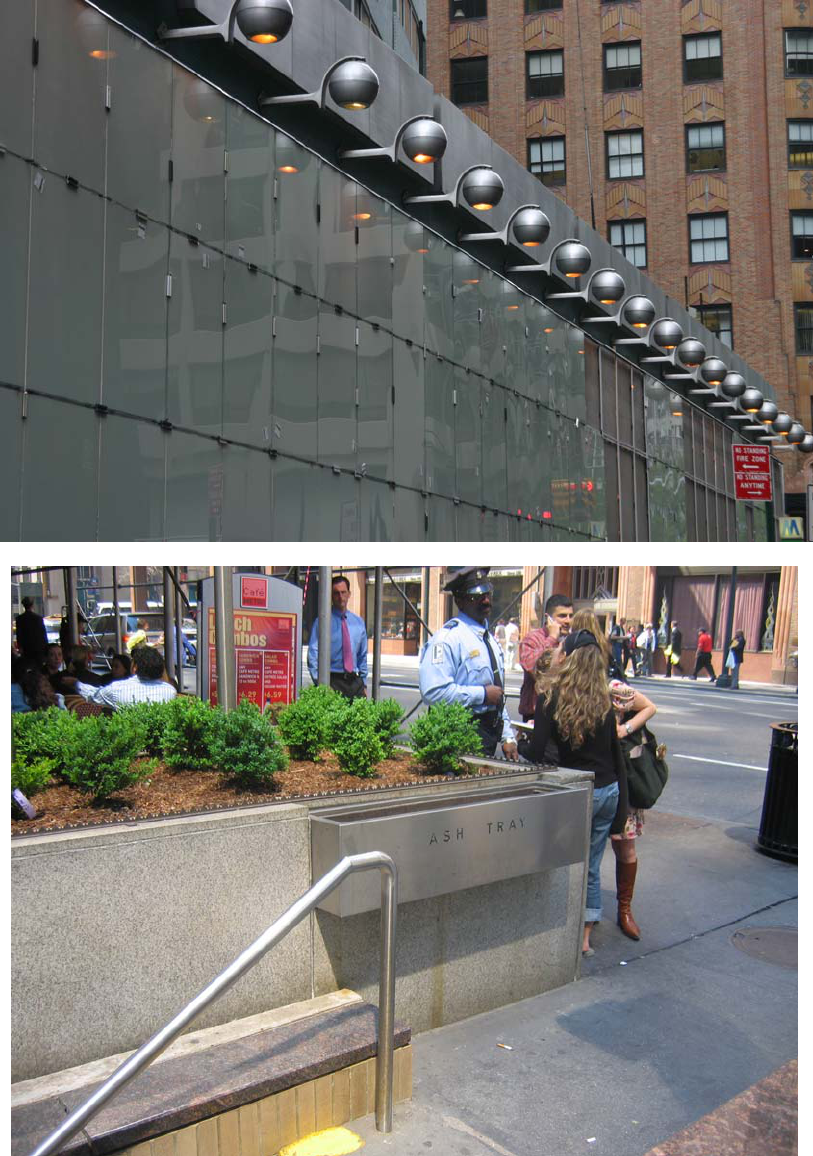

The main entrance faces Lexington Avenue. The stainless steel marquee, with recessed

lighting, is non-historic. There is a non-historic revolving glass door flanked by metal-framed doors

and non-historic green glass rectangles. Set at a slight angle to the avenue, the entrance is flanked by

storefronts. Both are larger than originally built, filling part of what was once a small plaza. Near the

corner of East 51

st

Street, projecting from the north storefront is the original raised planting bed. Clad

in the granite, it incorporates a stainless steel ashtray, as well as three lighting fixtures, currently

without glass covers. The south storefront is faced is dark red metal panels and dates from c. 1990. It

is taller that the structure it replaced (obscuring the base of the tower) and has streamlined features

that suggest the Art Deco style, including glass brick and curved corners.

Above the ground story, the entire west façade is windowless. The beige-colored aluminum

panels, replacing marble, are not original to the building. Close to the north edge of the west facade,

extending from approximately the seventh to the thirteenth floor is a projecting illuminated sign,

consisting of seven oval disks balanced between triangular stainless steel supports. It is approximately

seventy feet tall. The sign is original, though the arrangement of letters and imagery has been

changed.

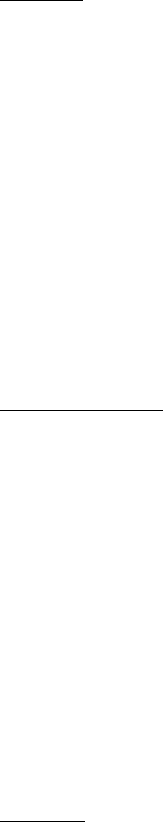

The north or East 51st Street elevation is the building’s most distinctive and visible feature –

a flattened S curve. This well-preserved façade can be best appreciated from 51

st

Street or looking

south along the west side of Lexington Avenue. At the lowest floor, it is engaged with the base,

obscuring part of the lowest floor. From the east edge of the site, where it meets the rear façade of 830

Third Avenue, it veers north and then south again before nearing Lexington Avenue. Each bay

consists of a projecting light green brick rectangle that floats against a dark green mosaic tile

background. At the center of each rectangle are two small air vents. The windows are non-historic

and were installed in 2005. Thicker than the original fenestration, the new windows appear to rest

between the brick panels. The width of each set of windows is identical, except for the set that aligns

with the tower, which is a third wider. The top of the uppermost floor (below the penthouse) is faced

in non-historic beige-colored aluminum panels. The penthouse, faced in green and clear glass and

vertical metal moldings, is three stories tall. Each suite adjoins a small outdoor terrace. The top level

is crowned by a projecting roof cornice. Above the penthouse, at mid-block, is a tall mechanical

tower, housing ventilation equipment and a water tower. The north side is faced with metal grilles and

the west side is clad with green brick. The south and east sides of the tower are difficult to see from

the street.

The south elevation is visible from Lexington Avenue with difficulty. Viewed at an acute

angle, it nearly identical to the East 51

st

Street façade except mid block where the non-historic

windows are interrupted by a solid wall of green brick.

Researched and written by

Matthew A. Postal

Research Department

9

NOTES

1

The section on Lapidus is mostly based on two versions of the architect’s autobiography: Morris Lapidus,

An Architecture of Joy

(1979) and Morris Lapidus,

Too Much is Never Enough

(Rizzoli, 1996).

2

Joseph Giovanni, “Life Throws Morris Lapidus a Few Good Curves,”

New York Times

, December 23,

1999, F8.

3

“New Concern by Building Designer,”

New York Times

, February 16, 1961, 51.

4

Giovanni; Mervyn Rothstein, “Morris Lapidus, an Architect Who Built Flamboyance Into Hotels, Is Dead

at 98,”

New York Times

, January 19, 2001, C11.

5

The section on the Tisch family is based on “Al Tisch, 63, Head of Hotel Chain,”

New York Times

,

February 3, 1960; “Hotel Man With a Bankroll,”

New York Times

, September 6, 1968, 59, and Christopher

Winans,

The King of Cash: The Inside Story of Laurence Tisch

(Wiley: New York, 1995).

6

Lapidus,

Too Much Is Never Enough

, 190-91.

7

Gilbert Millstein, “Architect De Luxe of Miami Beach,”

New York Times

, January 6, 1957, SM114.

8

Tisch purchased the hotel from Joseph Levy, president of Crawford Clothes. Lapidus designed several

stores for Crawford Clothes in the late 1940s.

9

Before the theater was built, the Nursery and Child’s Hospital complex was located on the site.

Established on St. Mark’s Place in 1854, the 51

st

Street hospital had brick buildings constructed in 1855,

1863, and 1888.

10

“Ground Will Be Broken Today for 21-Story Hotel,”

New York Times

, June 21, 1960, 29; “A Hotel

Boom is On,”

New York Times

, August 14, 1960, X18.

11

Lapidus,

Too Much is Never Enough

, 234.

12

Lapidus was familiar with Chatham Green. In 1973, he said: “So a snake dance on Lexington Avenue is

not satisfactory, while the one on Chatham Square is all right. Frankly, these barbs hurt.” John W. Cook

and Heinrich Klotz,

Conversations With Architects

(New York, 1973), 155.

13

Glenn Fowler, “First Reinforced Concrete Hotel in City Rises on Lexington Avenue,”

New York Times

,

March 19, 1961, R1. Also see, Morris Gilbert, “Proving Ground for Hotels,”

New York Times

, January 8,

1961, XXI.

14

Lapidus,

An Architecture of Joy

, 193.

15

“Ground Will Be Broken,” Olga Guelft, “What Do You Think of The Summit?”

Interiors

, October 1961;

David Dunlap, “Most Hated Hotel Reclaims Its Floridian Flamboyance,”

New York Times

, November 8,

2000, D1.

16

Lapidus,

An Architecture of Joy

, 217.

17

Ibid., 217-18.

18

Cook & Klotz,

Conversations With Architects

, 174.

19

Quoted in Susan Tunick,

Terra-Cotta Skyline

(Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), 81.

20

Quoted in Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman,

New York 1960

(Monacelli Press,

1995), 306.

21

Andrew Hepburn,

Complete Guide to New York City

(1964), 164.

22

A 1958 press release claimed that the brown color was selected “to capture the feeling of forward

thinking.” It was the ninth color introduced by Alcoa. See “Edifice Complex, “

FIT Network

(Spring

2005), 8.

23

The tiles quickly deteriorated and were later removed.

24

See Morris Lapidus Papers (1933-1988) in the collection of the Syracuse University Library.

25

Guelft.

26

“East Side Hotel Opens Tomorrow,”

New York Times

, July 30, 1961, 58.

27

“Advertising: Summit Hotel Drive Nears End,”

New York Times

, July 24, 1961, 40. “International Air

Marks Opening of Hotel,”

New York Times

, August 1, 1961, 28.

28

“International Air.”

29

Ada Louise Huxtable, “Our New Buildings: Hits and Misses,”

New York Times

, April 29, 1962, 213.

30

Lapidus,

Too Much is Never Enough

, 231; see Joseph and Shirley Wersherba Papers at the Center of

American History at the University of Texas at Austin.

31

Dunlap.

32

“Summit Gives In, Modifies Décor,”

New York Times

, October 20, 1961, 30.

10

33

Dunlap.

34

The owners include Goldman Sachs & Co., Highgate Holdings, and Oxford Capital Companies.

35

Letter to Preston Tisch, September 15, 2000; forwarded by Deborah Desilets to Jennifer Raab, Chairman

of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, September 16, 2000.

11

FINDINGS AND DESIGNATION

On the basis of a careful consideration of the history, the architecture and other

features of this building, the Landmarks Preservation Commission finds that the former

Summit Hotel has a special character, special historical and aesthetic interest and value as

part of the development, heritage, and cultural characteristics of New York City.

The Commission further finds that the Summit Hotel, located at the southeast corner

of Lexington Avenue and East 51

st

Street, is admired for its unusual shape, color, and

stainless steel sign; that it is an important mid-career work by the celebrated hotel

designer Morris Lapidus; that it was the first hotel built in Manhattan since 1930 and the

architect’s first hotel in New York City; that Lapidus was especially proud of this

building and reproduced an image of it on the cover of his autobiography,

The

Architecture of Joy

, published in 1979; that it is built of reinforced concrete and has

curving elevations that are faced in light green glazed brick and dark green mosaic tile;

that it is embellished with globe-shaped lighting fixtures, mosaic door handles, neon

signs, and a stainless steel ash tray that serves smokers descending into the subway; that

at the time of construction it generated considerable controversy but is now considered an

important example of the architect’s work; and that despite alterations to the Lexington

Avenue entrance, this modern hotel retains much of its original flamboyant character.

Accordingly, pursuant to the provisions of Chapter 74, Section 3020 (formerly

Section 534 of Chapter 21) of the Charter of the City of New York and Chapter 3 of Title

25 of the Administrative Code of the City of New York, the Landmarks Preservation

Commission designates as a Landmark the Summit Hotel, 569-573 Lexington Avenue

(aka 132-166 East 51

st

Street), and designates Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block

1305, Lot 50, as its Landmark Site.

Robert B. Tierney, Chair; Pablo Vengoechea, Vice-Chair

Stephen Byrns, Joan Gerner, Christopher Moore, Richard Olcott

Thomas Pike, Jan Pokorny, Elizabeth Ryan, Vicki Match Suna, Commissioners

Summit Hotel

569-573 Lexington Avenue (aka 132-166 East 51st Street)

View east

Photo: Carl Forster

Summit Hotel

West façade

Photo: Carl Forster

Summit Hotel

East 51st Street, façade and storefronts

Photos: Carl Forster

Summit Hotel

East 51st Street

Lighting fixtures and northwest corner

Photos: Carl Forster and Matthew A. Postal

Summit Hotel

Lexington Avenue entrance and storefront

Photos: Carl Forster

Summit Hotel

East 51st Street façade

Photos: Carl Forster

Summit Hotel

Sign on Lexington Avenue and East 51st Street entrance

Photos: Carl Forster

3

A

v

E

5

1

S

t

E

5

0

S

t

E

4

9

S

t

E

5

2

S

t

L

e

x

i

n

g

t

o

n

A

v

Lot 50

®

Summit Hotel (now Doubletree Metropolitan Hotel), 569-573 Lexington Avenue (aka 132-166 East 51st Street), Manhattan

Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map, Block 1305, Lot 50

Graphic Source: New York City Department of City Planning, MapPLUTO, Edition 03C, December 2003

Block 1305

3

A

v

E

5

1

S

t

E

5

0

S

t

E

4

9

S

t

E

5

2

S

t

L

e

x

i

n

g

t

o

n

A

v

569-573 Lexington Avenue

®

Summit Hotel (now Doubletree Metropolitan Hotel), 569-573 Lexington Avenue (aka 132-166 East 51st Street), Manhattan

Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map, Block 1305, Lot 50

Graphic Source: Sanborn Manhattan Land Book, 2004-2005, Edition 25, Plate 78