Ag Decision Maker

extension.iastate.edu/agdm

File A2-60

Crop Price Hedging Basics

Revised March 2022

The business of a crop producer is to raise and market

grain at a profitable price. As with any business, some

years provide favorable profits and some years do

not. Profit uncertainty for crop producers arises from

both variance in the cost of production per bushel

(especially from yield variability) and uncertainty of

crop prices.

Many techniques are used by producers to reduce risk

from production loss. These may include adequate

size of machinery, rotating crops, diversification of

enterprises, planting several different hybrids, crop

insurance, and many others.

Crop producers also have marketing techniques

which can reduce the financial risk from changing

prices. Rising prices generally are financially

beneficial to producers and falling prices are generally

harmful. However, it is never known with certainty

whether prices will rise or fall. Futures hedging can

help establish price either before or after harvest. By

establishing a price, the producer protects against

price declines, but also generally eliminates any

potential gain if prices rise. Thus, through hedging

with futures, producers can greatly reduce the

financial impact of changing prices.

How Prices are Established

Prices of corn and soybeans are established in two

separate but related markets. The futures market

trades contracts for future delivery. These future

contracts are traded at a commodity exchange and

are for a specific time (contract delivery month),

place (primarily Chicago, Illinois), grade (#2 yellow

shelled corn), and quantity (1,000 or 5,000 bushel

contract sizes). The cash market is where the physical

grain is handled by firms such as country elevators,

processors, and terminals.

The term basis refers to the price difference between

the local cash price and the futures price. The basis is

different at alternative marketing locations. Thus, for

effective marketing, it is important to be aware of the

local basis at country elevators, as well as at nearby

processors or terminals.

Local cash prices thus reflect two components: the

futures price and the local basis. Figure 1 helps

illustrate this point. As an example, a local cash bid of

$5.50 per bushel for corn may be derived from a

futures price of $5.70 and a local basis of $-.20. It is

helpful to think of local cash prices in terms of the

futures component and the basis component when

examining marketing alternatives.

The Hedging Concept

Producer hedging involves selling corn futures

contracts as a temporary substitute for selling corn

in the local cash market. Hedging is a temporary

substitute, since the corn will eventually be sold in

the cash market.

Hedging is defined as taking equal but opposite

positions in the cash and futures market. For

example, assume a producer who has harvested

10,000 bushels of corn and placed it in storage in a

grain bin. By selling 10,000 bushels of corn futures

the producer is in a hedged position. In this example,

the producer is long (owns) 10,000 bushels of cash

corn and short (sold) 10,000 bushels of futures corn.

Since the producer has sold futures, price has been

established on the major component of the local cash

price. This can be seen in Figure 1, which illustrates

that the futures component is the most substantial

portion of the local cash price.

Figure 1. Components of local cash corn prices

Page 2

Ag Decision Maker File A2-60, Crop Price Hedging Basics

Selling futures in a hedge leaves the local basis

unpriced. Thus, the final value of the corn is still

subject to fluctuations in local basis. However, basis

risk (variation) is much less than futures price risk

(variation). By selling futures, the producer has

eliminated the financial loss which would occur on

the cash grain from a futures price decline.

The hedge position is removed or lifted when the

producer is ready to sell the corn in the cash market.

It is lifted in a simultaneous two-step process. The

producer sells 10,000 bushels of corn to the local

grain elevator and immediately buys back

the futures position. The purchase of futures offsets

the original short (sold) position in futures, and

selling the cash grain converts the position to the

cash market.

Producer Hedging Illustrations

Hedging involves taking opposite but equal positions

in the cash and futures markets. If you own 10,000

bushels of corn as discussed above, you are long

cash corn. If you sell 10,000 bushels of corn on the

futures market you are short corn futures.

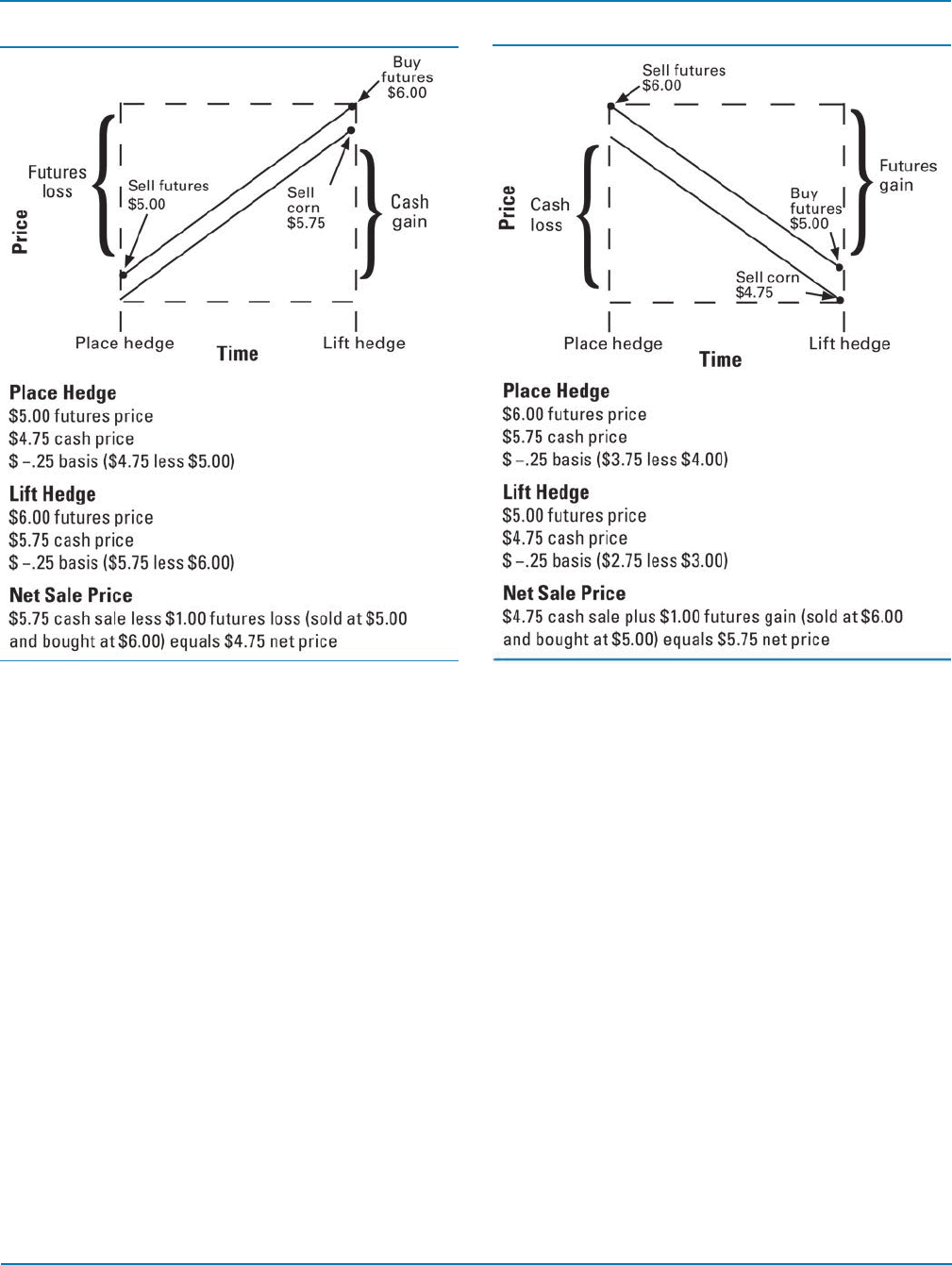

If the price increases as shown in Figure 2, the value

of the cash corn also increases. However, the futures

contract incurs a loss because you sold (short) corn

futures and now have to buy corn futures at the

higher price to close out the futures position. If both

the cash and futures prices increase by the same

amount, the increase in the value of the corn will

exactly offset the loss in the futures market. The net

price received from the hedge is exactly the same

as the cash price when the hedge was initiated (not

including trading cost, interest on margin money, or

storage costs).

Figure 2. Producer hedging in a rising market

Figure 3. Producer hedging in a declining market

Page 3

Ag Decision Maker File A2-60, Crop Price Hedging Basics

If the price decreases as shown in Figure 3, the value

of the cash corn also decreases. However, the futures

contract results in a gain because you sold (short)

corn futures and now can buy corn futures back at

a lower price to close out the futures position. If

both the cash and futures price decrease by the same

amount, the decrease in the value of the corn will

exactly offset the gain in the futures market. The net

price received from the hedge is exactly the same

as the cash price when the hedge was initiated (not

including trading cost, interest on margin money,

and storage costs.)

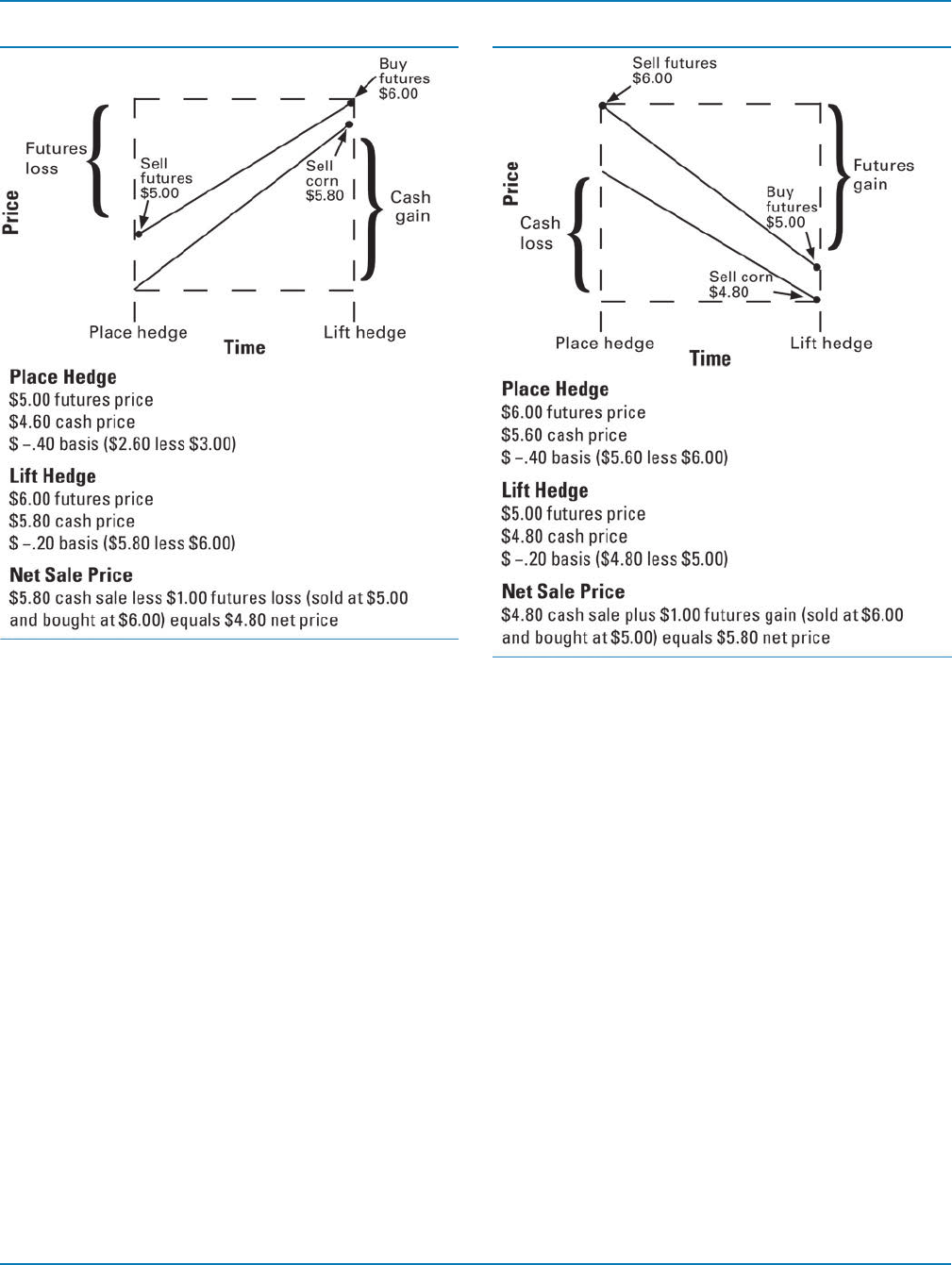

The difference between the cash price and

the futures price is the basis. The basis in the

illustrations in Figure 2 and 3 is the same when

the hedge is lifted as when it was initially placed.

However, if the basis is smaller when the hedge is

lifted as shown in Figure 4, the gain in the cash

market will be greater than the loss in the futures

market and the net price received from the hedge

will be slightly larger. The outcome is the same if

prices decline (Figure 5). The loss in value of the

cash grain will be less than the gain in the futures

market resulting in a higher net price.

Basis usually narrows from harvest into the winter,

spring and summer; resulting in a higher price.

However, a higher price is needed due to the cost

of storing grain past harvest. Whether the basis

narrows and by how much is not known until the

hedge is lifted. Although hedgers can lock in the

futures price when they hedge, they are vulnerable

to basis changes.

Hedging can also be used to establish a price for

a crop before harvest. Assume the hedge is placed

before harvest but lifted at harvest. The net price

(not including trading cost or interest on margin

money) is the futures price at the time the hedge

is placed, less the expected harvest basis. If prices are

higher at harvest, the higher cash price is offset by

the futures loss. If prices are lower, the futures gain

is added to the lower cash price.

Figure 4. Producer hedging in a rising market Figure 5. Producer hedging in a declining market

Page 4

Ag Decision Maker File A2-60, Crop Price Hedging Basics

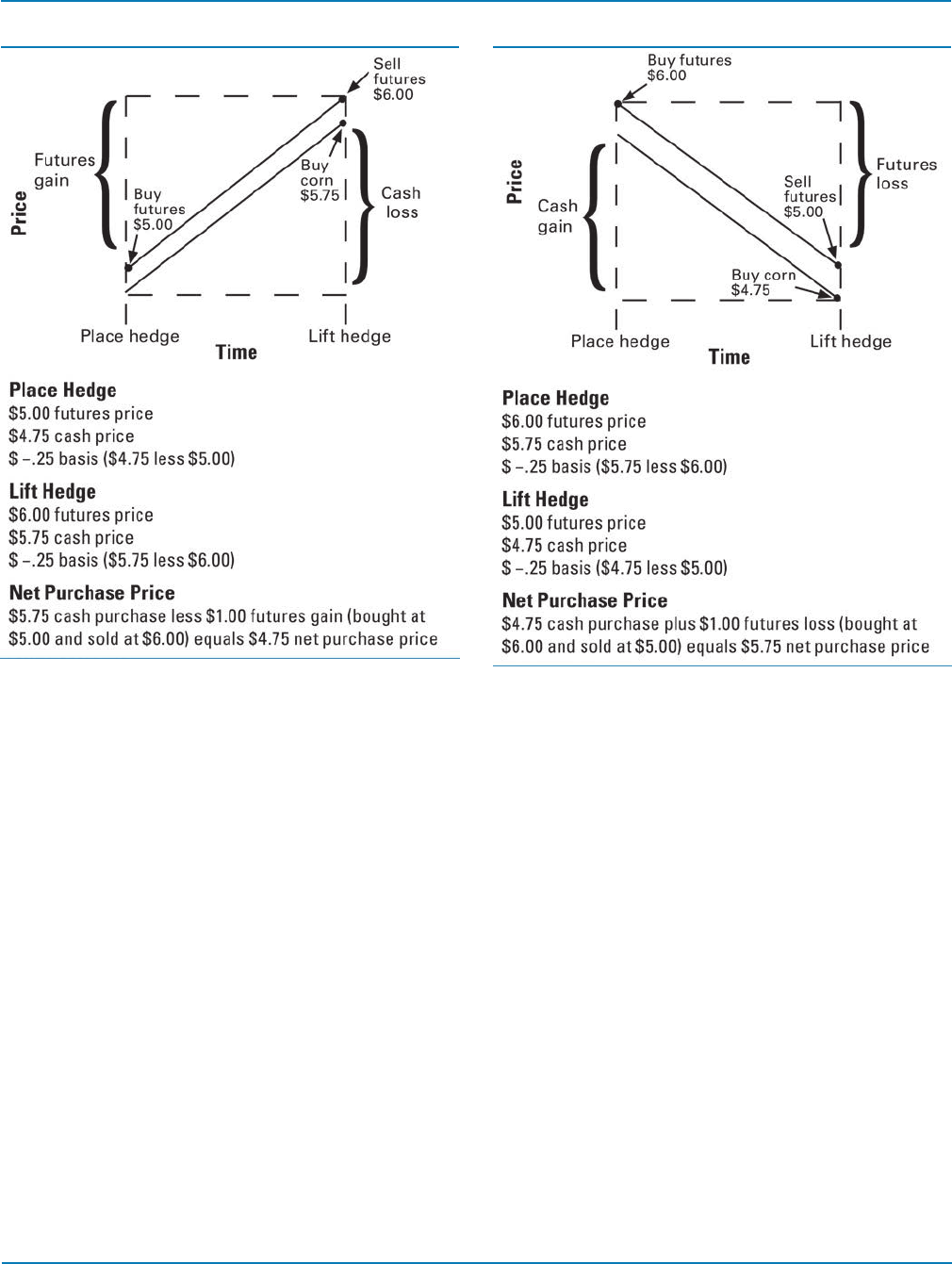

Processor Hedging Illustrations

If you are a grain processor or livestock producer

needing grain for processing or feed, hedging can

be used to protect against rising grain prices. Once

again hedging involves taking opposite but equal

positions in the cash and futures markets. But in this

case, you don’t have grain that you plan to sell but

rather plan to buy grain at a future time period to

fill your processing or feed needs. Instead of selling

futures at the time of placing the hedge, you buy

futures. So you own grain (futures) in the futures

market but are short grain in the cash market (will

need grain but don’t own any).

If grain prices rise as shown in Figure 6, you make

money in the futures market because you purchased

futures and can now sell them at a higher price.

However, the grain for processing or feed needs

now cost more. So the gain in the futures market

offsets the increase in the grain purchase price.

If grain prices drop as shown in Figure 7, the

futures you purchased at the beginning of the

period must now be sold at a lower price. How-

ever, the grain for your processing or feed needs

now cost less. So the loss in the futures market

offsets the decrease in the grain purchase price.

If the difference between the cash and futures

prices remains the same over the hedging period,

the loss in one market will exactly offset the gain

in the other market (not considering transaction

and interest costs).

Figure 6. Processor hedging in a rising market Figure 7. Processor hedging in a declining market

Page 5

Ag Decision Maker File A2-60, Crop Price Hedging Basics

Mechanics of Placing a Hedge

Once hedging principles are understood, a key

decision in the hedging process is selecting the

right method to carry out the trades. This could

be a brokerage firm, elevator, processor, or online

trading platform that offers a hedging program.

A producer should expect the firm to execute

orders accurately and quickly and often serve as

a source of market information. Most firms have

daily market reports as well as periodic in-depth

research reports on the market outlook which

may be useful in formulating a marketing strategy.

Also, a broker or merchandiser that is familiar with

local cash market opportunities has some distinct

advantages.

It is extremely important that the firm understands

how hedging and price risk management fit into

the marketing program of the producer. The

producer and the broker or merchandiser must

realize that hedging is a tool to reduce price

risk. However, producers sometimes use futures

markets to speculate on price changes and thus

are exposed to increase price risk. Generally,

speculation and hedging should be done in two

separate accounts. Inexperienced hedgers should

seek a broker or merchandiser willing to help them

increase their understanding of market mechanics.

After selecting a broker or merchandiser,

formulating a marketing plan, and opening a hedge

account, the producer is ready to place trading

orders. The broker or merchandiser can supply

information on the types of orders to place. Once

the broker or merchandiser receives the order, it

will be placed with the commodity exchange. The

order will be placed electronically, and it will be

executed, provided it is within the current market

range. A confirmation of the executed order is then

relayed back to the local broker or merchandiser.

To maintain a position in the futures market,

producers must deposit margin money with the

trading firm. Initial margin requirements provide

financial security to insure performance on the

futures commitment. If the producer sells (buys) a

contract in the futures market and the futures price

subsequently rises (declines), this represents a

loss of equity in the futures position. These higher

(lower) prices may require additional funds to

maintain the hedge position. If the futures price

moves down (up); the producer who sold (bought)

futures will have futures profits credited to their

account. The producer can call for this excess

margin to be paid to them. In the futures market,

the margin position is updated each day.

Margin calls should not be viewed as a loss but

rather as part of the cost of insuring against a

major price decline (increase). In a producer

hedged position, losses on futures contracts are

offset by the increasing value of the physical grain

inventory. In a processor (livestock producer)

hedged position, losses on futures contracts are

offset by lower priced cash grain purchases.

Although margin calls should not be viewed as

a loss, they complicate a producer’s cash flow.

If prices rise, the futures loss must be paid

(additional margin) as the loss accrues. However,

the additional value of the grain is not realized

until the grain is sold when the hedge is lifted. For

grain processors and livestock producers, falling

grain prices can result in margin calls before the

benefits of lower priced cash grain purchases are

realized. So, a cash flow problem may occur.

Once the position is closed out, the producer is no

longer required to maintain a margin account (for

that transaction). Thus the producer (processor)

can receive their margin deposits, plus (minus)

futures profits (losses), less brokerage fees.

Revised by Kelvin Leibold, farm management

field specialist,

Original author Don Hofstrand, retired extension

value added agriculture specialist

www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm

This institution is an equal opportunity

provider. For the full non-discrimination

statement or accommodation inquiries, go to

www.extension.iastate.edu/diversity/ext.