Liquidity risks arising

from margin calls

June 2020

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Executive summary

2

Central clearing and margin requirements in the bilateral sphere bring high benefits to financial

stability and more particularly in terms of management of counterparty credit risk. Greater central

clearing of derivatives and collateralisation of non-centrally cleared derivatives positions have

significantly strengthened the resilience of derivatives markets since the aftermath of the 2008

financial crisis. These reforms – led by the G20/Financial Stability Board – helped to ensure that

recent market stress has not resulted in widespread concern about counterparty credit risk. Central

clearing also maximises netting opportunities that achieve greater capital and collateral efficiency,

including in respect of variation margin payments that mechanically reflect movements in market

prices.

The coronavirus crisis and the recent oil market disruption caused a sharp drop in asset prices and

increased volatility, resulting among others in significant margin calls across centrally cleared and

non-centrally cleared markets. This report documents two financial stability-related issues: (i) large

amounts of margins called from mid-February to mid-April, which may further increase due to likely

forthcoming credit rating downgrades and possible further market volatility, as well as (ii) the

adverse impact of such margin calls on both bank and non-bank entities, also in view of market

concentration and interconnectedness.

This report proposes a recommendation addressed to the competent authorities in the area of

central counterparties (CCPs), banks and other relevant market participants, encompassing the

following aspects:

1. To the extent compatible with the overarching objective of avoiding jeopardizing the resilience

of counterparties, limit sudden and significant (hence procyclical) changes and cliff effects in

initial margins (including margin add-ons) and in collateral practices: (i) by CCPs vis-à-vis

members; and (ii) by clearing members vis-à-vis their clients; as well as (iii) in the bilateral

market, resulting from the mechanistic use of external credit ratings and possibly procyclical

internal credit scoring methodologies.

2. Include in CCPs liquidity stress testing any two defaulting entities regardless of their role vis-à-

vis the CCP, including liquidity providers to the CCP, to enhance the liquidity resilience of

CCPs by taking into account risks from the systemic, macroprudential perspective related to

the high degree of interconnectedness among CCPs and their liquidity service providers. The

policy also proposes to consider conducting coordinated liquidity stress tests at the EU and/or

global level.

3. To the extent compatible with CCPs’ operational and financial resilience, limit unnecessary

liquidity constraints for clearing members and clients related to operational processes for

margin collection.

4. Steer discussions at international level, through the participation of relevant competent

authorities in international fora and standard setting bodies, where applicable, on means to

mitigate the procyclicality in margin and haircut practices when providing client clearing

services. These discussions should pursue the feasibility assessment, as well as the design

Executive summary

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Executive summary

3

and set up of global standards governing minimum requirements for risk management when

providing client clearing services – both centrally cleared and non-centrally cleared.

The report also proposes further policies to be considered and analyses to be carried out over the

short to medium term within the ESRB’s structures. Notably, the ESRB could:

1. Recommend to the European Commission to consider the possibility of amending Level 1 or

Level 2 regulation in order to require CCPs to implement an accelerated pass-through of

intraday variation margins, whenever operationally possible and wherever the risk

management framework would not be negatively impacted.

2. Independently assess the antiprocyclicality performance of the International Swaps and

Derivatives Association (ISDA) SIMM model

1

used widely for calibrating margin exchanges in

bilateral derivatives transactions.

3. Analyse the structure of the clearing market in Europe from a financial stability perspective

and its resilience in times of stress, focusing on interconnectedness and concentration in the

provision of clearing services by CCPs and clearing members (also in view of increased

market activity). If needed, recommend adjustments to prudential requirements for managing

concentration risk at the CCP and clearing member level. In this regard, due consideration

should be given to the existing global standards developed by the Basel Committee on

Banking Supervision (BCBS), the committee of Payments and market infrastructures (CPMI)

and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) in order to ensure a

regulatory level playing field with other major jurisdictions.

4. Promote the continued sharing of relevant information by authorities, within their mandate and

respecting confidentiality, and jointly develop analytical tools to enhance the ESRB analytical

toolkit.

Finally, this report conveys the message that CCPs limit dividend payments to shareholders and

earnings distributions to parent companies, or take equivalent action to build up their own funds.

This would help ensure that CCPs maintain adequate prefunded own resources, in addition to initial

margins and default funds, not least in view of increased operational risks.

1

The ISDA Standard Initial Margin Model (SIMM) is an industry-led standardised methodology for calculating initial margin

requirements for non-centrally cleared OTC derivatives.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Key issues identified

4

Central clearing and margin requirements in the bilateral sphere bring high benefits to

financial stability and more particularly in terms of management of counterparty credit risk.

Greater central clearing of derivatives and collateralisation of non-centrally cleared derivatives

positions have significantly strengthened the resilience of derivatives markets since the aftermath of

the 2008 financial crisis. These reforms – led by the G20/Financial Stability Board – helped to

ensure that recent market stress has not resulted in widespread concern about counterparty credit

risk. Central clearing also maximises netting opportunities that achieve greater capital and collateral

efficiency, including in respect of variation margin payments that mechanically reflect movements in

market prices.

This report considers the implications of significant margin calls from cash and derivative

positions across the financial system. As the COVID-19 and oil market crisis caused a sharp

drop in asset prices and high levels of market volatility, these developments also resulted in a

significant increase in margin calls from cash and derivative positions.

2

Going forward, these could

have major implications for the liquidity management and funding needs of counterparties, and

possibly even their solvency in a scenario where liquidity stress leads to systematic fire sales of

assets. This report considers the implications for the financial system, in particular focusing on

financial stability risks that could emerge from large margin calls and how these risks could be

mitigated. The report acknowledges that central clearing and margin requirements in the bilateral

sphere bring high benefits to financial stability and that policy action on margins must not

jeopardise protection against counterparty credit risk. Derivatives counterparties, including CCP

clearing members and their clients, should ensure they maintain sufficient liquidity to meet margin

calls in timely fashion. It is though also beneficial, from a financial stability perspective, to ensure

that CCPs’ risk management decisions do not overburden clearing members, their clients and

counterparties because of excessively procyclical features, thus creating unwelcome liquidity

strains, possibly developing into solvency issues.

Recent episodes of high market volatility have led to a substantial increase in margins.

Margin increases have taken place through several channels embedded in the risk management

framework of CCPs (serving the derivative and cash markets) and bilateral OTC derivatives:

(i) initial margin (collateral covering potential future portfolio losses originating from the default of

the counterparty); (ii) variation margin (payments to settle the mark-to-market moves on open

positions); and (iii) intraday margin calls (which cover both mark-to-market moves and the

recalibration of initial margins on account of heightened volatility, leading to greater potential future

losses). In particular, from mid-February to mid-April, initial margins have increased in the wake of

higher transaction volumes, but also because of the response of margin models to higher potential

future losses due to higher market volatility and tail risks.

3

For example, for the cleared segment of

derivative transactions, the total initial margin posted by EU clearing members at the four largest

2

Data in this report rely on EMIR data and thus relate to derivatives transactions. However, anecdotal evidence shows that

FX swap and cash market segments, such as equities, have behaved in a similar fashion.

3

For further details on margining types and factors behind recent margin increases, see item B.1 in Annex B.

1 Key issues identified

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Key issues identified

5

CCPs in the EU and in the United Kingdom had increased by ca. €34 billion by the end of March,

4

i.e. by more than one-third of the pre-crisis level (see Chart 1, as well as Charts A.1 and A.2 in

Annex A). Margins are fundamental to how a CCP manages counterparty credit risk and are an

integral part of the risk management of counterparties and support systemic resilience.

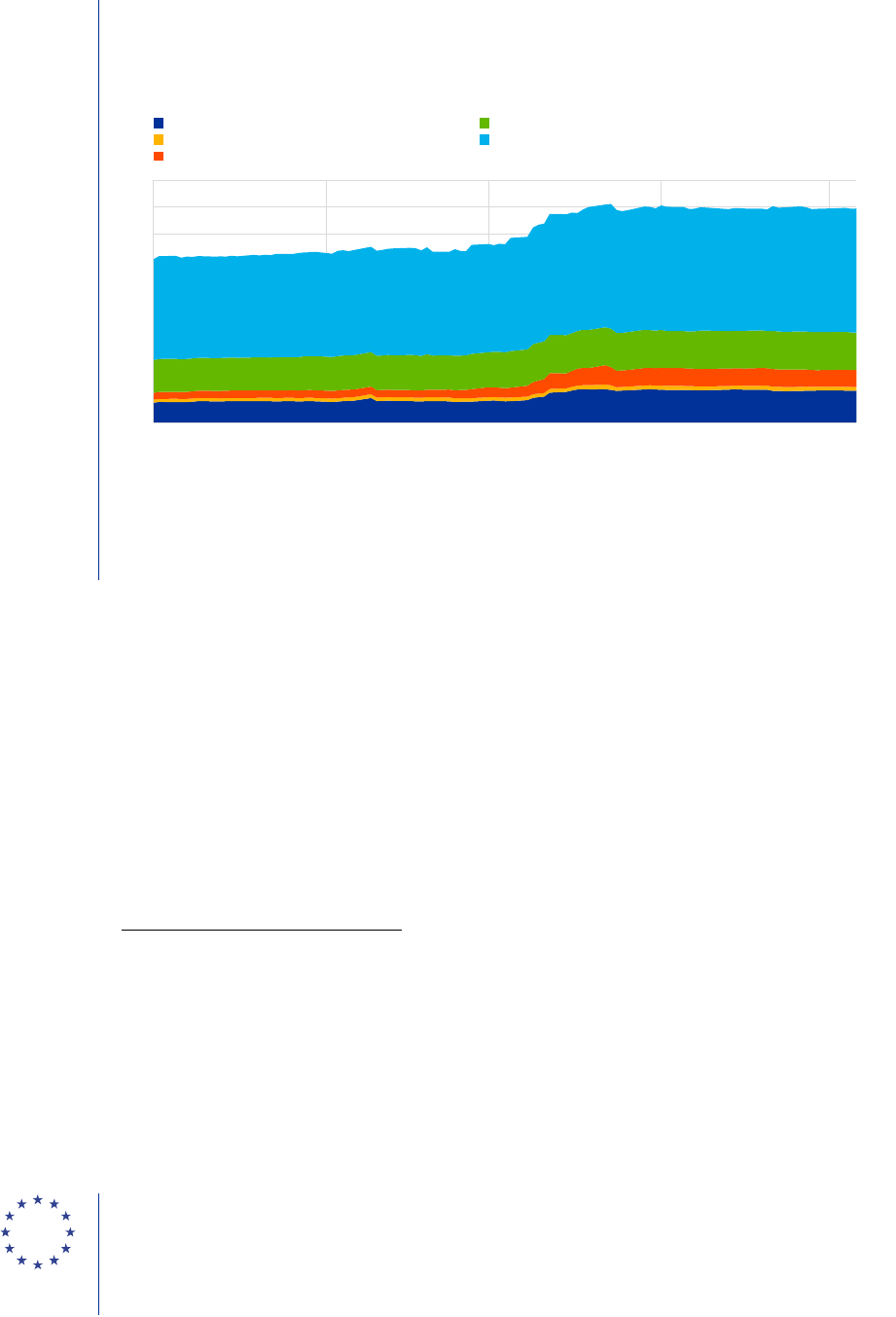

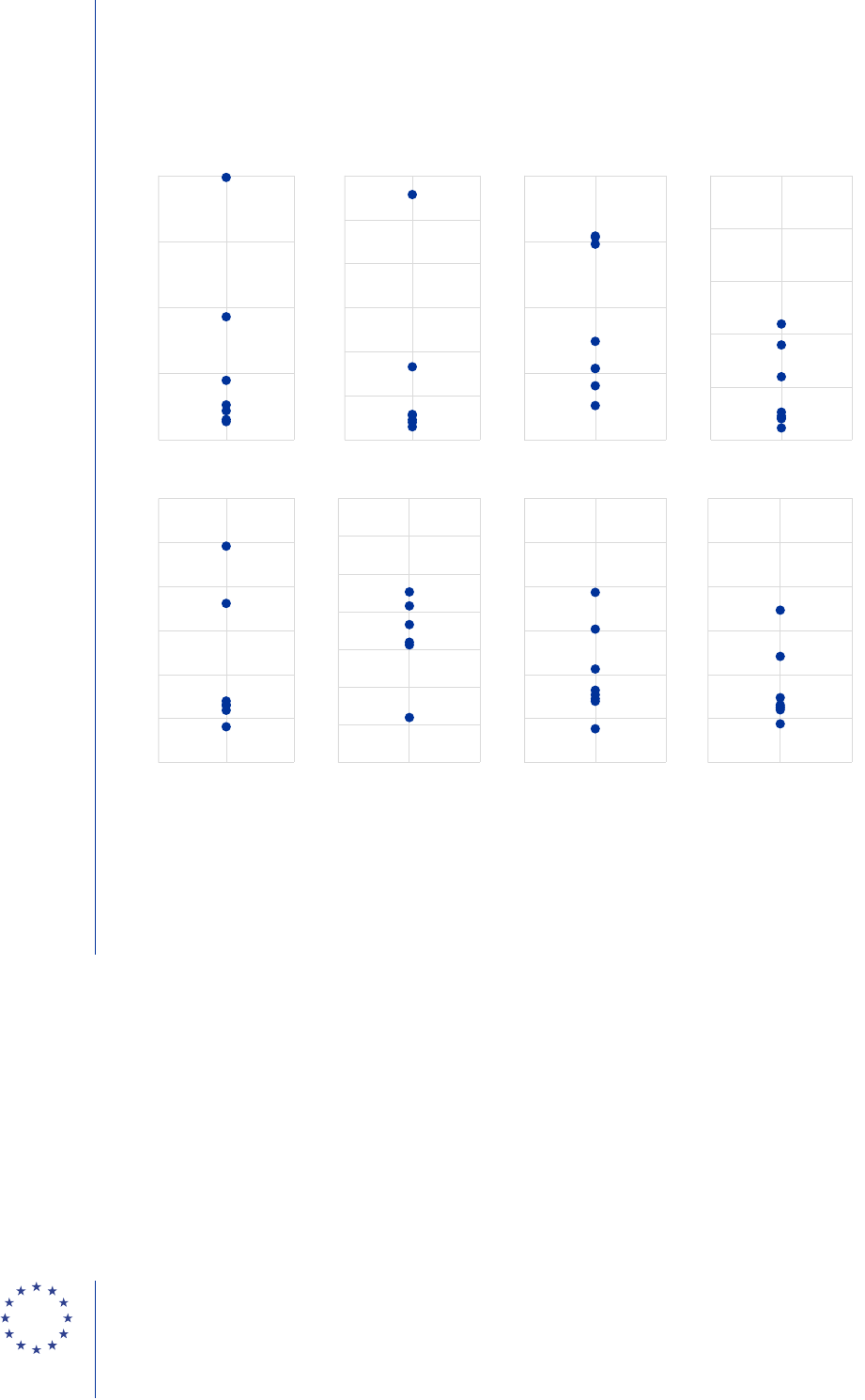

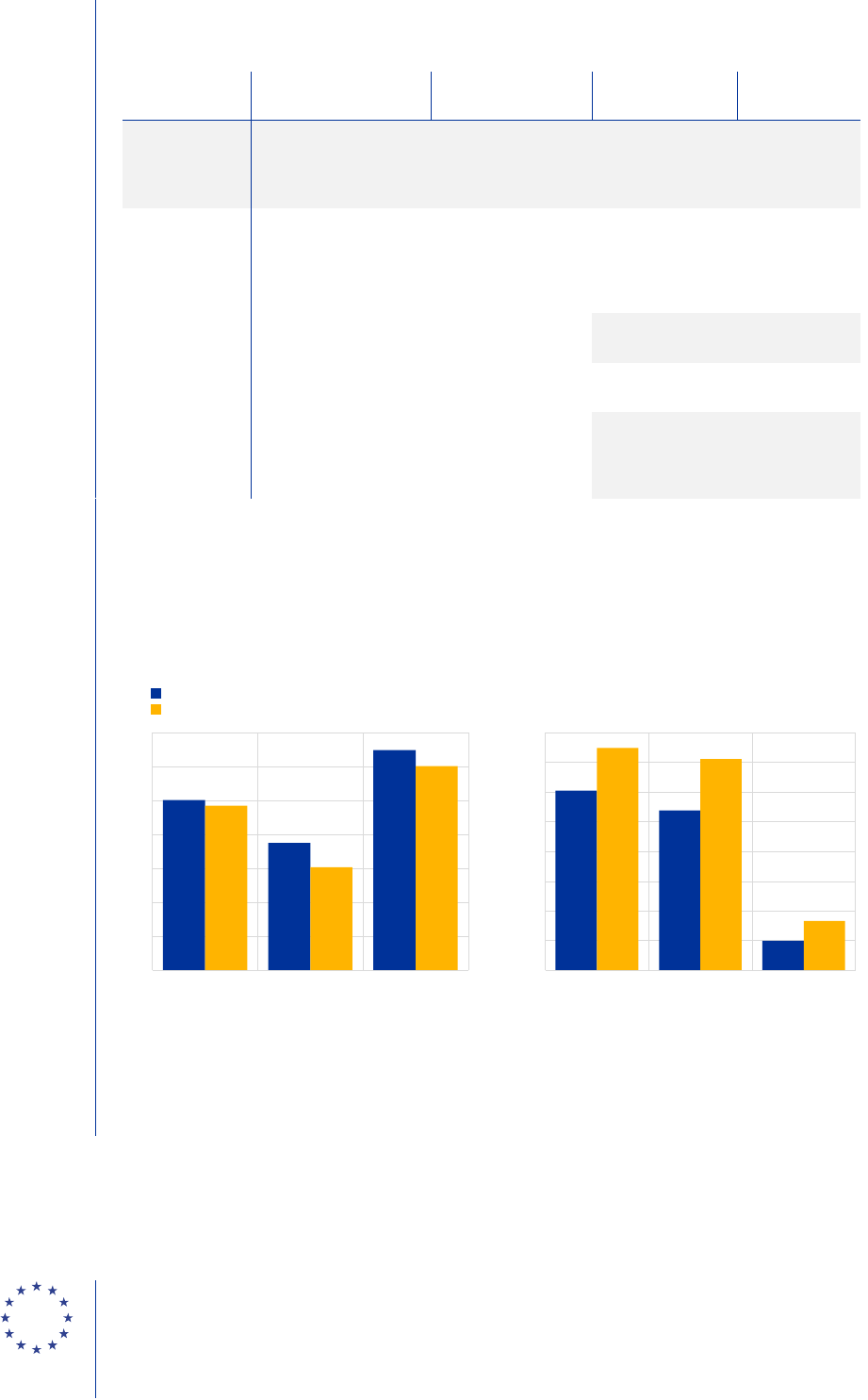

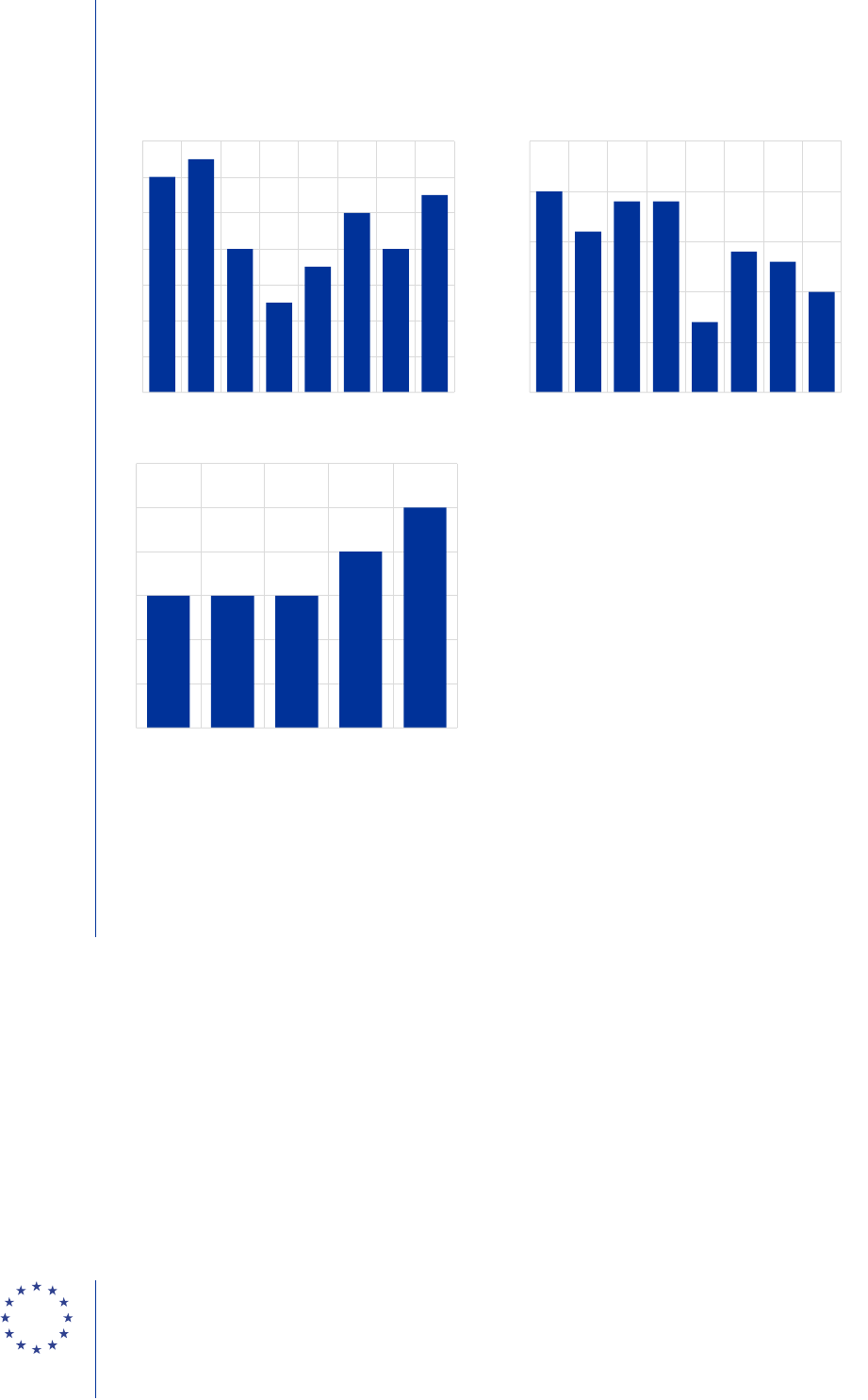

Chart 1

Initial margins posted in EU and UK CCPs by area of the CCP and the clearing member

(EUR billions)

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board trade repository data

5

and ESRB Secretariat calculations based on joint work with the

ECB.

Note: The chart includes data for the largest four CCPs (in terms of initial margins) in the EU and the United Kingdom vis-à-vis

their respective clearing members. The latest observation is for 7 May 2020.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, CCPs have called large amounts of intraday

margin to cover market movements, with the corresponding variation margin payout often

occurring only the next morning, causing liquidity to be temporarily trapped on the accounts

of the CCPs. As highlighted by the ESRB

6

, in some markets CCPs call and collect intraday

margins to cover market movements from loss-making positions together with margin to cover

potential exposures on existing and newly novated positions. As a result, while clearing members

with loss-making positions provide margin to the CCPs to cover this exposure, clearing members

with profit-making positions do not receive the corresponding variation margin payout until the next

day, resulting in the liquidity being held at CCPs overnight during times when it could be most

needed in other areas of the system. During recent weeks, the total amounts of variation margins

have increased substantially (see Chart 2). For one country, the trading data have been cross-

checked with supervisory data on the CCP’s intraday margin calls, which showed that intraday

4

Overall, in the cleared segment of derivatives transactions, initial margins at the four largest CCPs in the EU and in the

United Kingdom increased from ca. €300 billion to ca. €400 billion between January 2020 and end-March 2020. This refers

to the total across all clearing members at any of the four CCPs, including legal entities outside the EU. Of this, €34 billion

was called from EU clearing members, with a surge of €28 billion (80%) in March alone.

5

Trade repository data (or EMIR data) refers to the data accessed by the European Systemic Risk Board based on the

European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR).

6

European Systemic Risk Board (2020b), Mitigating the procyclicality of margins and haircuts in derivatives markets

and securities financing transactions, January 2020.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

01/20 02/20 03/20 04/20 05/20

EU CCPs – EU clearing members

EU CCPs – Rest of the world clearing members

EU CCPs – UK clearing members

UK CCPs – EU clearing members

UK CCPs – non-EU clearing members

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Key issues identified

6

margin calls mainly resulted from market movements (i.e. variation margins) on days of high

volatility, and that variation margin gains were not paid out intraday but on the following morning.

Currently intraday margin calls are not passed on in many CCPs for several reasons, e.g. because

these calls cover both mark-to-market changes and top-ups for initial margins on an intraday basis,

or because some CCPs accept non-cash collateral for meeting intraday margin calls, which would

make it challenging to pass on the same day.

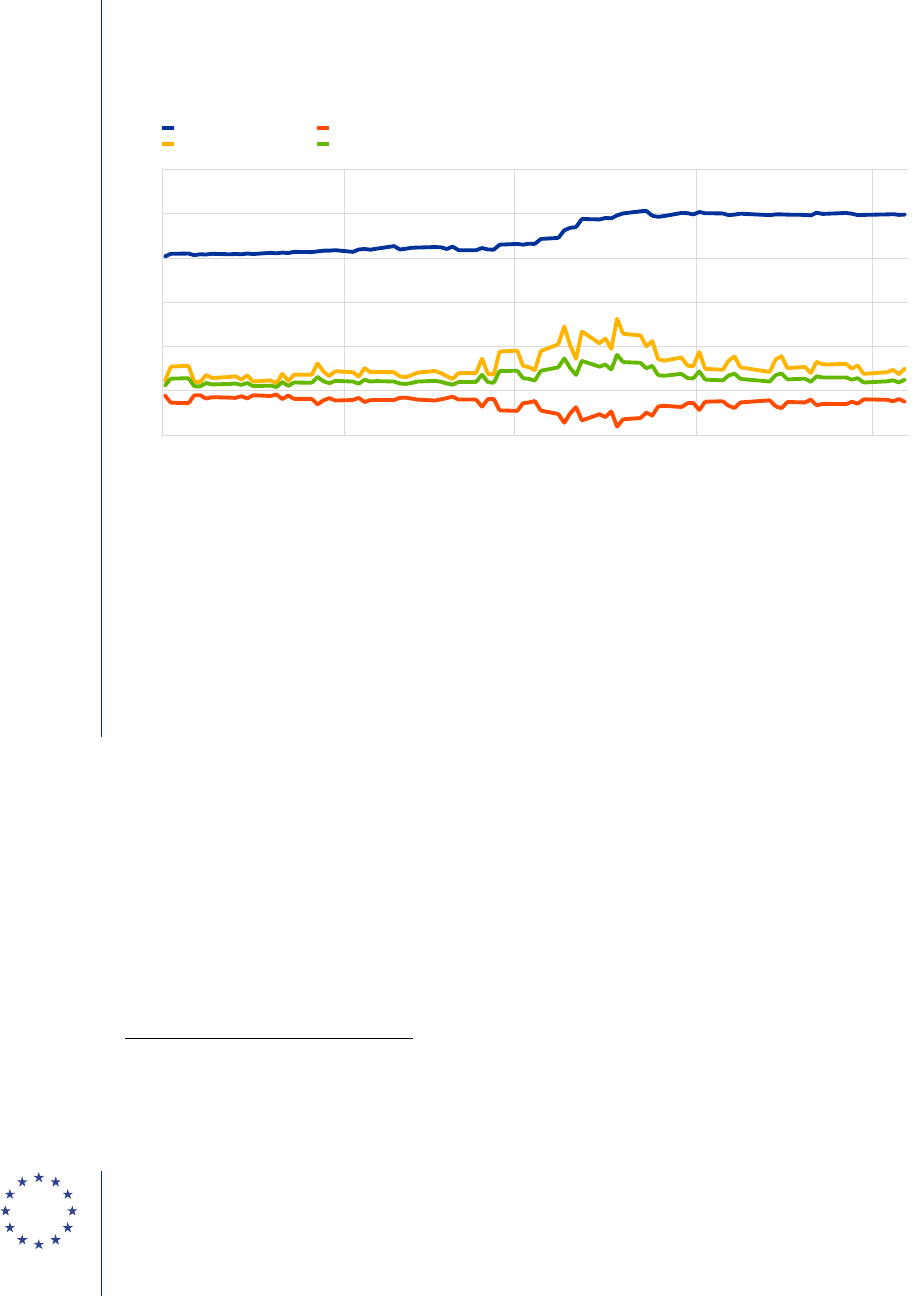

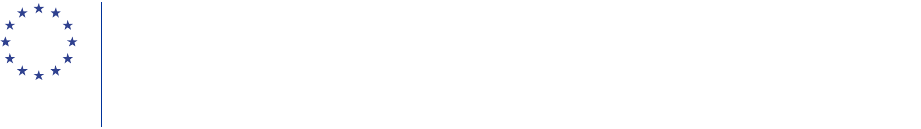

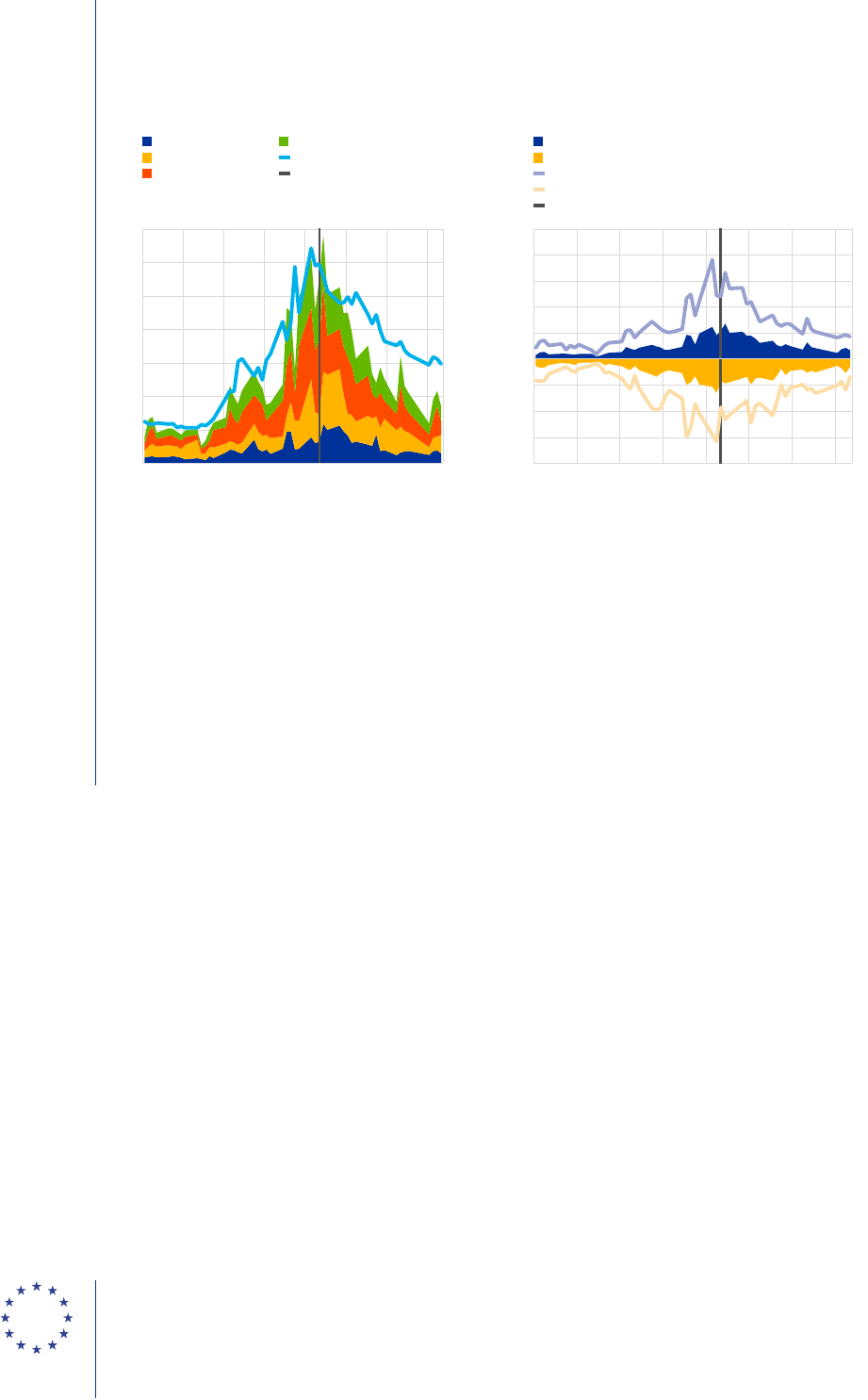

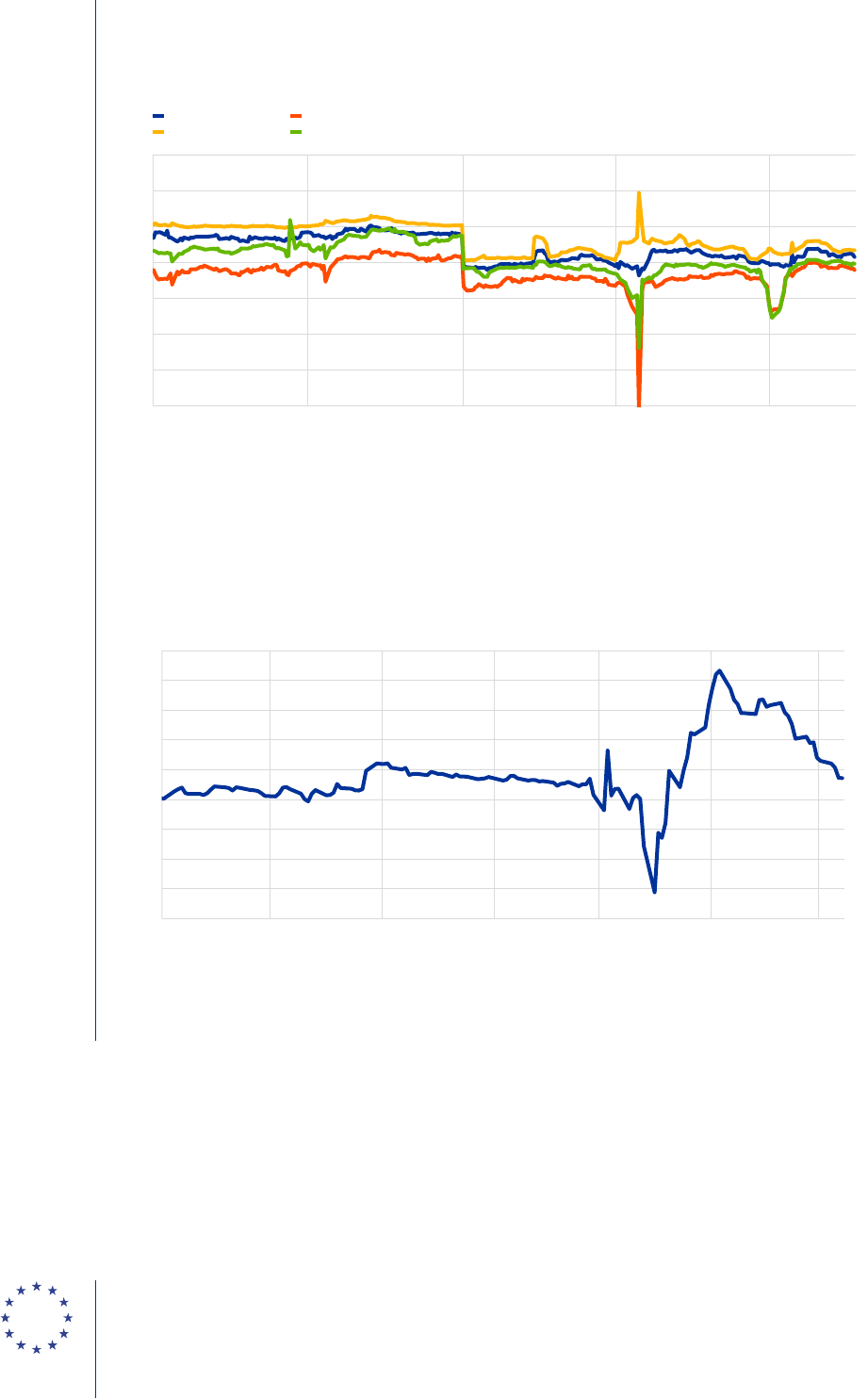

Chart 2

Initial and variation margins posted in four EU and UK CCPs

(EUR billions)

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board EMIR data. ESRB Secretariat calculations based on joint work with the ECB.

Note: The chart includes data for the largest four CCPs (in terms of initial margins) in the EU and United Kingdom vis-à-vis their

respective clearing members. The latest observation is for 7 May 2020. The chart shows a comparison of initial and variation

margins posted and received at the four largest CCPs in the EU and the United Kingdom by initial margins (clearing members

from all jurisdictions are included in the aggregates). Gross flows proxies the total amount of liquidity flowing from clearing

members to the CCPs plus the amount from the CCPs to the clearing members until the end of the day. Variation margin

received by the CCPs proxies the amount of clearing members’ cash liquidity needs. Variation margin posted by the CCPs

proxies the amount of cash liquidity received by clearing members. The share of variation margin posted by the CCPs resulting

from intraday margin calls reflects the liquidity subject to a delayed pass-through for some CCPs. The results for each CCP

have been validated with national sources. The methodology has been developed in cooperation with the Deutsche

Bundesbank.

Margin frameworks have responded broadly as expected so far, reflecting the smooth

functioning of cleared and bilateral markets and timely payouts by market participants.

7

Market participants have met margin calls in centrally cleared markets with only minor operational

delays in some cases, which they promptly solved without putting counterparties at risk. In the

bilateral market, the number of disputes has markedly increased, but total amounts have remained

stable. Clearing members have also continued to post high levels of excess collateral at CCPs,

which could be interpreted as a precaution against future margin calls or, possibly, as a sign that

market participants have not so far faced widespread difficulties in sourcing collateral.

7

See also some evidence on the functioning of the repo market in item B.2 in Annex B.

-100

0

100

200

300

400

500

01/20 02/20 03/20 04/20 05/20

Initial margins

Gross flow

Variation margin posted

Variation margin received

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Key issues identified

7

Some banking entities have seen a particularly marked increase in initial margins and may

have experienced increased liquidity constraints (see Chart 3 and Table A.4 in Annex A), in

terms of cash and collateral available. Such strains could be problematic, should the situation

materially worsen, in view of the high concentration and interconnectedness of the derivatives

markets among several large clearing members.

8

However, capital and liquidity requirements are

relatively favourable for derivative positions (see also Table A.5 in Annex A) and major banks under

the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) have entered this crisis with robust capital and liquidity

positions. In addition, authorities have introduced substantial policy support measures to alleviate

potential liquidity and solvency strains and have incentivised banks to make prompt use of their

buffers. Overall, so far major European clearing members have not reported any significant delays

in meeting margin calls. Currently, major euro area clearing members exceed regulatory liquidity

requirements, and they now also have access to additional liquidity support (e.g. through the

temporary easing of the ECB’s collateral requirements), so that they can be expected to have

sufficient balance sheet space to support client needs if necessary.

Margin calls have likely affected non-bank entities significantly, in bilateral markets or via

client clearing, due to liquidity constraints.

9

According to recent ECB analysis

10

, the daily

variation margin calls on euro area investment funds’ derivative exposures quintupled. For a

substantial share of funds with derivative exposures, the variation margin call exceeded their pre-

crisis cash positions on at least one day during the turmoil. In addition, 6% of funds did not have a

sufficiently large pre-stress liquidity position to cover the cumulative increase in variation margin

during the market turmoil.

11

Furthermore, increases in initial margins posted at CCPs during March

2020 stemmed mainly from client portfolios and to a somewhat lesser extent from house portfolios

(due to comparatively limited house business).

12

Such developments may be of concern given that

most non-banks rely on the services of only one client clearing provider

13

and do not have back-up

arrangements in place. Therefore, clearing providers typically have extensive discretion to change

clearing conditions for their clients in a short period of time, including changes in initial margin

calibrations as well as collateral eligibility. As discussed by the ESRB

14

, current client clearing

arrangements leave clearing members substantial leeway for counterparty-specific add-ons on

initial margins (of up to 50%). While clearing service providers’ collateral requirements are typically

aligned with those of CCPs, clearing providers’ repo desks typically offer (but are not contractually

8

See also the evidence on interconnectedness and concentration in Figures A.1 and A.2 and Tables A.1-A.3 in Annex A.

9

For a more detailed discussion and further evidence on the concentration of client clearing, the impact on non-bank

financial entities and non-financial corporations, as well as on the functioning of the bilaterally cleared FX market, see items

B.3-B.5 in Annex B.

10

See Charts A.3-A.5 in Annex A and Fache Rousová, L., Gravanis, M., Jukonis, A. and Letizia, E. (2020), “Derivatives-

related liquidity risk facing investment funds”, European Central Bank Financial Stability Review, Special Feature B,

May 2020.

11

For further evidence of possible liquidity constraints in non-bank financial entities, see de Jong, A., Draghiciu, A., Fache

Rousová, L., Fontana, A. and Letitia, E. (2019), Impact of variation margining on insurers' liquidity: An analysis of

interest rate swap positions, EIOPA, 2019, as well as Danmarks Nationalbank (2019), “Pension companies will have

large liquidity needs if interest rates rise”, November 2019.

12

See evidence in Chart A.2 in Annex A. House portfolios mean clearing members’ own portfolios, as opposed to the

portfolios of clearing members’ clients.

13

See also evidence in Table A.3 and Figure A.2 in Annex A.

14

European Systemic Risk Board (2020b), Mitigating the procyclicality of margins and haircuts in derivatives markets

and securities financing transactions, January 2020.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Key issues identified

8

obliged to provide) collateral transformation services to their clients, which increases client

dependency on the clearing provider.

Going forward, the ability of market participants to meet margin calls will depend on future

levels of volatility and the ongoing resilience of their liquidity management (although

solvency risks cannot be excluded). Other important potential channels of liquidity strains

include measures taken by CCPs to mitigate credit risk stemming from collateral issuers or clearing

members.

15

So far, there is only anecdotal evidence that some CCPs have taken action in this

regard. However, CCPs’ risk management practices may still reflect downgrades by credit rating

agencies (either of collateral issuers or of counterparties), which are also likely to materialise in the

future weeks and months. Any downgrade-related changes which are directly reflected in the

collateral or counterparty policies might imply that counterparties need to post or substitute large

amounts of collateral at short notice (e.g. where a measure affects domestic government bonds

which are frequently used as collateral), or even result in them being excluded from both clearing

facilities and the bilateral segment of the market. Overall, concentration at CCPs and clearing

members and interconnectedness among CCPs through common clearing members, liquidity

providers, custodians or investment counterparts may also lead to further cascade effects.

15

For further background, see items B.6-B.7 in Annex B.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Key issues identified

9

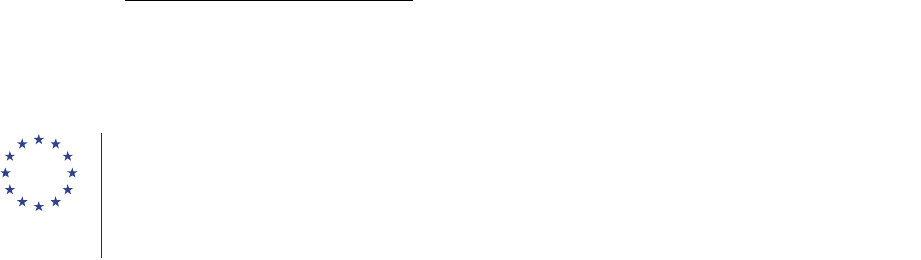

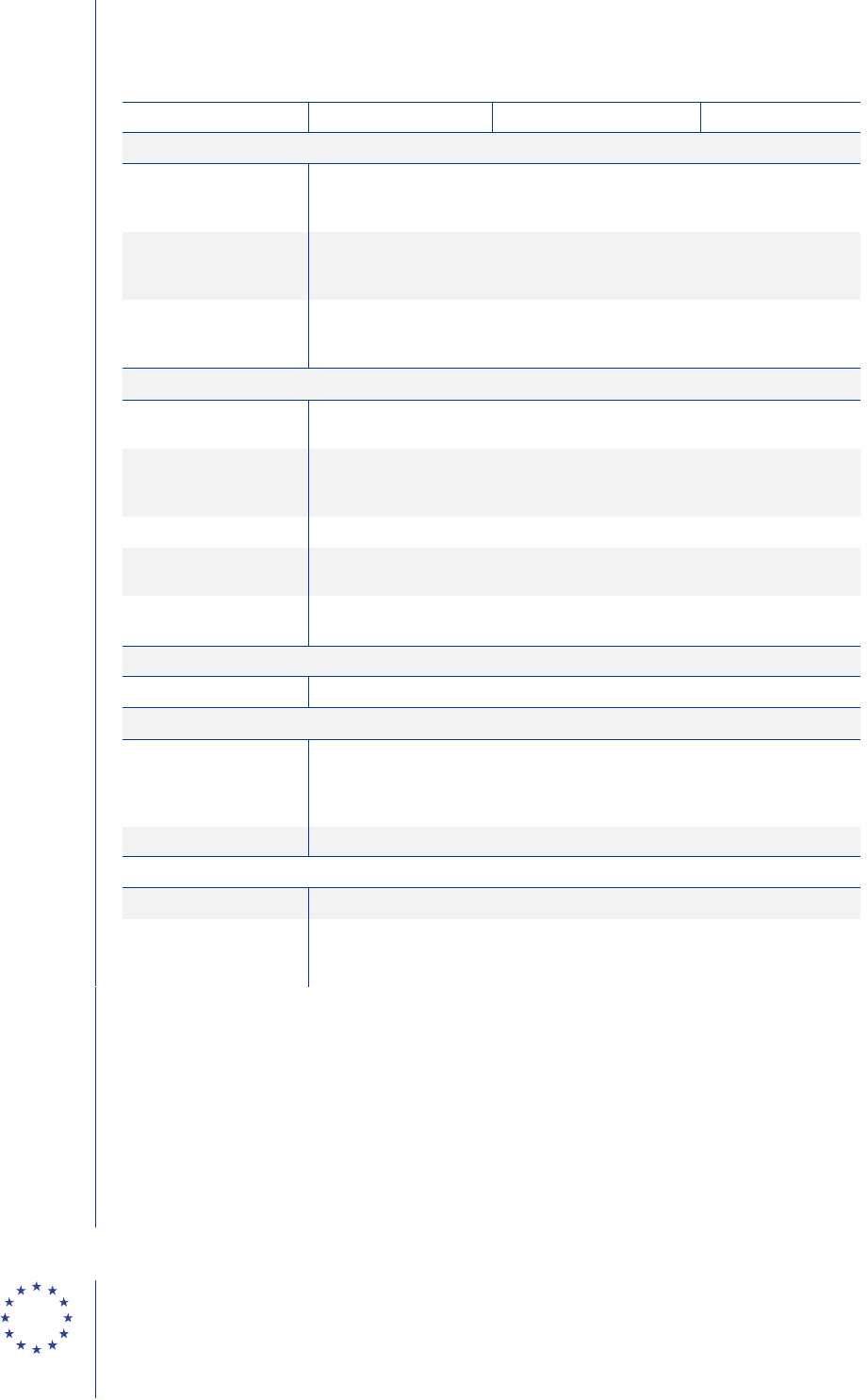

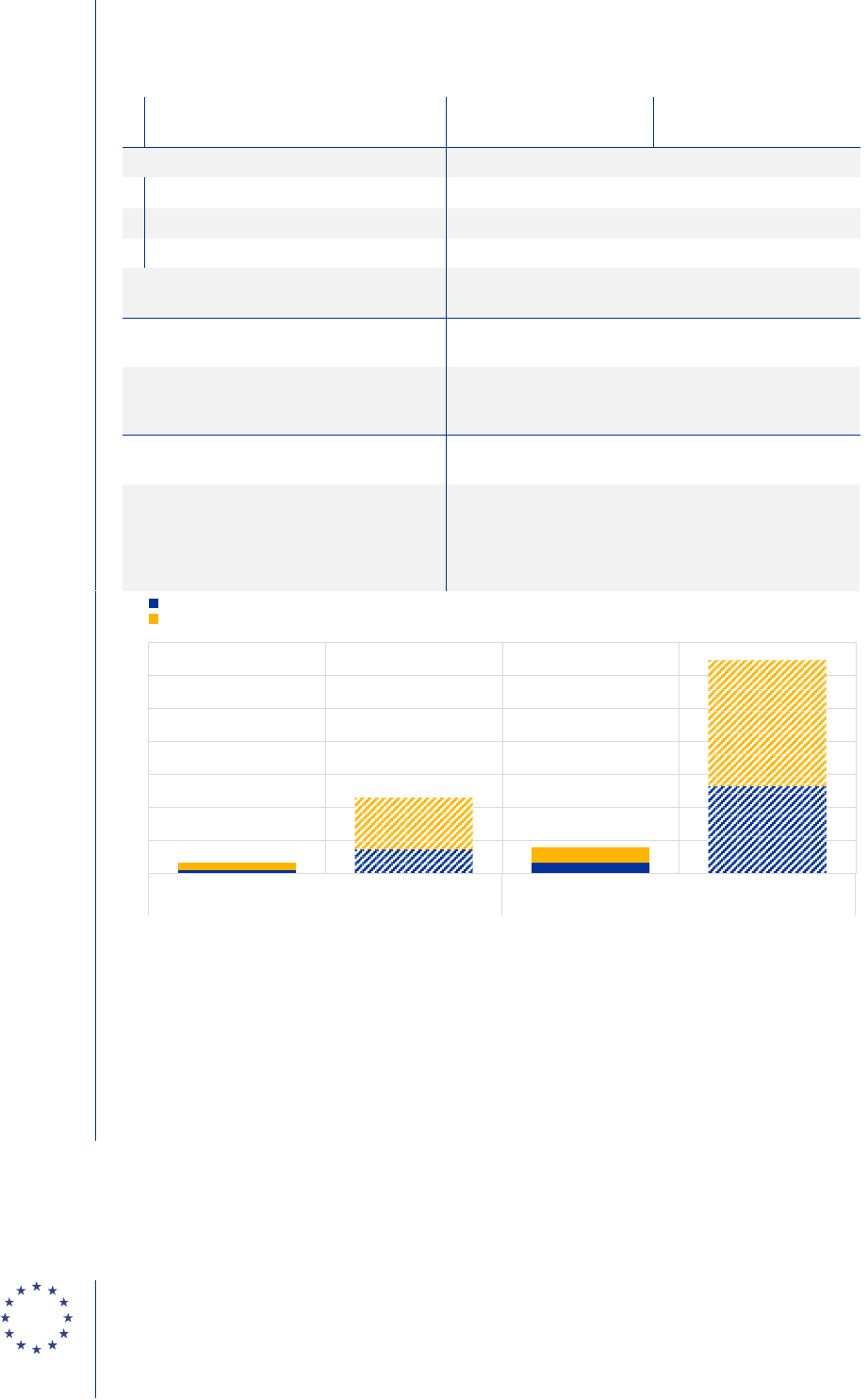

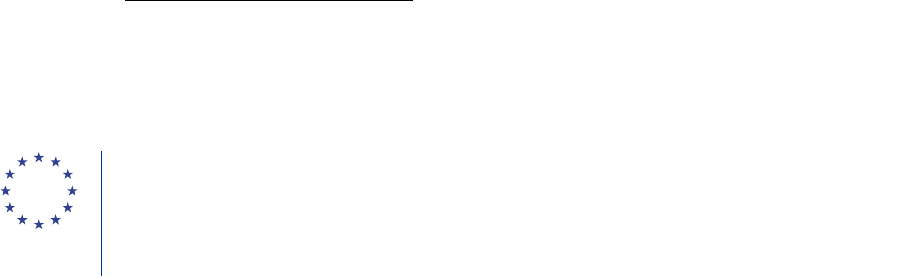

Chart 3

Initial margins (IM) posted as at the end of March and called during Q1 2020 for several

European banks relative to their capital, cash holdings, debt securities holdings and total

assets

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board EMIR data, SNL and the ESRB Secretariat’s calculations.

Notes: The charts present the amount of initial margin outstanding at EU and UK CCPs for several European banks with

relatively high initial margins at the end of March 2020 (upper panel) and initial margin called in Q1 2020, as a ratio of CET1

(SNL Table 220292), cash holdings of these banks, defined as cash and balances with central banks (SNL Table 246025), debt

securities holdings (SNL Table 224927) and total assets (SNL Table 132264) as at the end of 2019. Banks are presented on an

anonymised basis for confidentiality reasons. For one bank, the values of margin called relative to cash (ca. 62%) are not shown

in the scatter plot for presentational reasons.

0%

50%

100%

150%

200%

IM outstanding to

capital

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

120%

IM outstanding to

cash

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

IM outstanding to total

debt instruments

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

IM outstanding to total

assets

-20%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

IM called to capital

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

IM called to cash

-3%

0%

3%

6%

9%

12%

15%

IM called to total debt

instruments

-1%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

IM called to total

assets

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Policies to mitigate risks to financial stability

10

In view of the identified financial stability risks that could emerge from large margin calls,

the report proposes that the European Systemic Risk Board should immediately advocate

four policies which could be implemented through one recommendation to the relevant

Competent Authorities (in the areas of CCPs’, banking and other financial market

participants). To the extent possible, EU authorities should also promote these policies in

international fora, as they may affect EU market participants active in other jurisdictions and

to promote a level playing field across the clearing network at global level.

Policy 1. To the extent compatible with the financial resilience of counterparties, limit

sudden and significant (hence procyclical) changes and cliff effects in initial margins

(including margin add-ons) and in collateral framework: (i) by CCPs vis à vis members; and

(ii) by clearing members vis-à-vis their clients; as well as (iii) in the bilateral market,

resulting notably from the mechanistic use of external credit ratings and possibly

procyclical internal credit scoring methodologies.

The ESRB recommends that national competent authorities (NCAs) of the CCPs:

1. ensure that CCPs’ issuer and counterparty credit risk management frameworks (a) use

progressive and granular steps, in particular when implementing ratings downgrades, without

unduly delaying the feeding of these downgrades in their overall risk management practices

and (b) limit procyclical features in internal models, including by considering appropriate

margins of conservatism;

2. inform authorities represented in the respective EMIR College, when (and to the extent it does

not interfere with the timely implementation of risk management decisions, before) CCPs

implement a reduction in the scope of eligible collateral, or any material increase in collateral

“haircuts”, or any decrease in the concentration limits on the amount of collateral accepted

from a single issuer;

3. engage with CCPs (and possibly intermediaries for non-centrally cleared trades) to thoroughly

analyse the antiprocyclicality performance of the tools they have used during the most acute

periods of stress, and report on these analyses to their supervisory authorities.

Purpose: Limiting sudden and significant (hence procyclical) changes and cliff effects both in the

initial margin framework (including margin add-ons) and collateral framework would aim at reducing

sharp increases in initial margin requirements and consequently collateral demand. This in turn

would alleviate funding pressures for clearing members and clients.

When considering margin

increases by CCPs, EMIR already addresses the need to maintain antiprocyclicality tools in order

to limit procyclicality. Nevertheless, management of (issuer and counterparty) credit risk can also

have harmful procyclical effects and lead to liquidity strains. These result from: (i) the use of credit

rating agency (CRA) ratings, as downgrades can lead to automatic procyclicality; (ii) internal CCP

haircut models and credit scoring methodologies. This is not addressed by EMIR. Concerning the

initial margins applied by clearing members to their clients, the current market practice, especially

2 Policies to mitigate risks to financial

stability

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Policies to mitigate risks to financial stability

11

in equity and listed derivative clearing, is that clearing members increase collateral requirements

and collateral haircuts vis-à-vis their clients more than proportionally (by a multiple of more than

one) compared with what the CCP actually requires of them for their clients positions. This

conservative approach might vary according to: (i) the type of counterparty; as well as (ii) the credit

quality of counterparts. This might amplify liquidity drains for CCP end-users. Currently, there is no

provision in international standards setting minimum requirements regarding the risk management

practices between clearing members and their clients. Therefore there is no provision in the EU

framework in this regard, nor does the framework require clearing members to enforce

antiprocyclical margin management practices. While the amendments known as the “EMIR Refit”

enhance the transparency around margin setting between CCPs and clearing members, the same

transparency does not yet extend sufficiently to the relationship between clearing members and

their clients, in the absence of an international standard in this regard. Counterparties and in

particular CCPs should apply this recommendation in a way which is compatible with their ongoing

financial resilience.

Policy 2. Include in CCPs liquidity stress testing any two defaulting entities regardless of

their role vis-à-vis a CCP, including liquidity providers to the CCP, to enhance the liquidity

resilience of CCPs by taking into account risks from the systemic and macroprudential

perspective related to the high degree of interconnectedness among CCPs and their

liquidity service providers. The policy also proposes to consider conducting coordinated

liquidity stress tests at the EU or global level.

The ESRB recommends that the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) review its

draft technical standards under Article 44(2) of Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 so that CCPs include

in their liquidity stress test the default of any two entities providing services to a CCP that could

affect its liquidity situation. Currently they limit their framework to the default of any two clearing

members, as put forward by ESMA in the liquidity stress testing exercise in 2019. For example, the

default of any entity acting as an investment and repo counterparty, payment agent, custodian or

liquidity provider should be envisaged when selecting the two defaulting entities with the largest

impact on the liquidity position of the CCP, even if they are not a clearing member. Any existing

back-up arrangement would be taken into account. This will improve the overall market resilience,

in view of a large degree of concentration and interconnection among CCPs and their liquidity

service providers and, consequently, the fact that prudent liquidity management at individual CCP

level might not necessarily cover the risks from the systemic, macroprudential, perspective.

Pending the action taken by ESMA to comply with the above mentioned recommendation and the

possible introduction of corresponding EU legislation, it is recommended that competent authorities

ensure that the stress scenarios under Article 44 of Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 include the

default of any two entities that provide services to the CCP and whose default could materially

affect the liquidity position of the CCP. NCAs should encourage CCPs to react to any identified

weakness as a result of this enhanced stress test in a way that does not create additional burdens

on its members. For example, this could mean encouraging a CCP to find additional liquid

resources, but not imposing further limits on the collateral eligibility.

Considering the large concentration in the provision of liquidity services, as well as global

interconnections between CCPs and liquidity service providers, competent authorities should

engage with CCPs – and to the extent possible with other relevant authorities in third countries – to

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Policies to mitigate risks to financial stability

12

conduct coordinated liquidity stress test exercises. These should include the default of any two

entities that provide liquidity services to CCPs and whose default could materially affect the liquidity

positions of CCPs. This coordinated exercise could take place at the EU level or at a global level.

Purpose: In their liquidity stress testing CCPs should capture comprehensively all the events that

may cause them to face a liquidity shortfall.

16

This would incentivise CCPs to mitigate their reliance

on a liquidity provider. Since there is a significant degree of concentration in the provision of

liquidity and payment services to CCPs, this would enhance overall stability at market infrastructure

level. The conduct of coordinated liquidity stress test exercises globally or at the EU level could

also increase resilience in the liquidity risk management frameworks of CCPs in the EU.

Policy 3. To the extent compatible with CCPs’ operational and financial resilience, limit

unnecessary liquidity constraints for clearing members and clients related to operational

processes for margin collection

The ESRB recommends that NCAs encourage CCPs to the extent legally possible to ensure that

their operational (either variation or initial) margining frameworks (including schedules) do not lead

to unsurmountable operational liquidity constraints that may crystallise in default events. This could

in particular be achieved by:

1. Where operationally possible and to the extent that it does not materially affect the capacity of

the member to use it for the novation of new transactions, CCPs should consider the

possibility of offsetting excess collateral against intraday margin calls.

2. Where operationally and legally possible, provided that the risk management framework is not

negatively impacted and the capacity of the CCPs to manage their intraday margins and

settlements flows is not materially affected, CCPs should identify separately:

(a) intraday margins covering potential exposures, including exposures due to positions

entered into and novated on that day;

(b) intraday margins covering realised exposures due to market movements on that day,

which CCPs should consider paying out to clearing members whose positions have

positive mark-to-market values as soon as possible, and possibly on the same

settlement day.

Purpose: To the extent operationally and legally feasible, and compatible with their risk

management frameworks, CCPs should seek to ensure that their operational processes for the

collection of margins are predictable, transparent and limit liquidity strains in the financial system.

Limiting the liquidity trapped in CCPs would involve encouraging CCPs to the extent legally

possible to limit the asymmetry embedded in the current operational clearing framework. Currently,

most CCPs call intraday margins covering both potential future exposures and negative mark-to-

market adjustments, and positive mark-to-market adjustments are passed to members only at the

end of the day or even the next day. This CCP practice could give rise to cash constraints for

clearing members, as well as potential liquidity drains for their clients. However, CCPs would need

16

This builds up on an Opinion published by ESMA.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Policies to mitigate risks to financial stability

13

to consider the suitability of this policy for their operational processes, accounting processes and

risk management framework and the impact on their clearing members. In some markets, intraday

prices are not fully transparent and intraday margin calls are based on proxies and collected in non-

cash.

Policy 4. Recommend to competent authorities to engage in discussions at international

level, through their participation in international fora and standard setters bodies, on means

to mitigate the procyclicality in margin and haircut practices when providing client clearing

services. These discussions should pursue the feasibility assessment, as well as the design

and set up of global standards governing minimum requirements for risk management when

providing client clearing services – both centrally cleared and non-centrally cleared.

Purpose: The legal framework governing the provision of clearing services in relation to all

derivative and cash contracts and for non-cleared repo contracts should aim at explicitly mitigating

the procyclicality in margin and “haircut” practices. This would aim at making liquidity planning as

predictable and manageable as possible by reducing unexpected and significant cash calls, and

providing reasonable and enforceable notice periods for any changes in the initial margin and

haircut protocols to ensure that markets participants can adapt smoothly. Discussions should be

engaged in the relevant standard setting bodies in order to consider the design and set up of global

standards in this regard. This should be pursuant to already existing provisions in regulatory

technical standards for risk-mitigation techniques for OTC derivative contracts not cleared by a

central counterparty.

The report also proposes further policies to be considered and analyses to be carried out

over the short to medium term within the ESRB’s structures. Notably, the ESRB could:

1. Recommend that the European Commission considers the possibility of amending Level 1 or

Level 2 regulation in order to require CCPs to implement pass-through of intraday variation

margins, whenever operationally and legally possible and, provided that the risk management

framework is not negatively impacted, and to the extent it does not materially affect the

financial resilience of the CCPs.

2. Independently assess the antiprocyclicality performance of the ISDA SIMM model used widely

for calibrating margin exchanges in bilateral derivatives transactions.

3. Analyse the structure of the clearing market in Europe from a financial stability perspective

and its resilience in times of stress, focusing on interconnectedness and concentration in the

provision of clearing services by CCPs and clearing members (also in view of increased

market activity).If needed recommend adjustments to prudential requirements for managing

concentration risk at the CCP and clearing member level. In this regard, due consideration

should be given to the existing global standards developed by the Basel Committee on

Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions

(IOSCO) in order to ensure a regulatory level playing field with other major jurisdictions.

4. Promote the continued sharing of relevant information by authorities, within their mandate and

respecting confidentiality, and jointly develop analytical tools to enhance the ESRB analytical

toolkit.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Policies to mitigate risks to financial stability

14

Finally, this report conveys the message that CCPs limit dividend payments to shareholders

and earnings distributions to parent companies, or take equivalent action to build up their

own funds. This would help ensure that CCPs maintain adequate prefunded own resources

in addition to initial margins and default funds, not least in view of operational risks.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

References

15

Acosta-Smith, J., Ferrara, G. and Rodriguez-Tous, F. (2018), “The impact of the leverage ratio

on client clearing”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No 735, 15 June 2018.

Avellaneda, M. and Cont, R. (2013), “Close-Out Risk Evaluation (CORE): A new risk-

management approach for central counterparties”, Finance Concepts.

Bank for International Settlements (2019b), “The Basel Framework: Calculation of RWA for

credit risk”.

Bank for International Settlements (2019c), “The Basel Framework: Leverage ratio”.

Bank for International Settlements (2019d), “The Basel Framework: Liquidity coverage ratio”.

Bank for International Settlements (2019e), “The Basel Framework: Net stable funding ratio”.

Bank of England (2019), “Does the reliance of principal trading firms on banks pose a risk to

UK financial stability?” August 2019.

Bardoscia. M., Bianconi, G. and Ferrara, C. (2019a), “Multiplex network analysis of the UK OTC

derivatives market”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No 726, 18 May 2018.

Bardoscia, M., Ferrara, G., Valise, N. and Yoganayagain, M. (2019b), “Simulating liquidity stress

in the derivatives market”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No 838, 20 December 2019.

Bartholomew, H. (2020), “After coronavirus rout, concerns raised about Simm”, Risk.net, April

2020.

Cont, R. (2017), “Central clearing and risk transformation”, Norges Bank, March 2017.

Danmarks Nationalbank (2019), “Pension companies will have large liquidity needs if interest

rates rise”, November 2019.

de Jong, A., Draghiciu, A., Fache Rousová, L., Fontana, A. and Letitia, E. (2019), “Impact of

variation margining on insurers' liquidity: An analysis of interest rate swap positions”,

EIOPA, 2019.

Duffie, D. (2018), “Post-crisis bank regulations and financial market liquidity”, Baffi Lecture,

March 2018.

Duffie, D., Scheicher, M. and Vuillemey, G. (2015), “Central clearing and collateral demand”,

Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 116(2), pp. 237-256.

Glasserman P. and Wu, Q. (2018), “Persistence and procyclicality in margin requirements”,

Management Science, 64(12), pp. 5461-5959.

References

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

References

16

El-Omari, Y., Fiedor, P., Lapschies, S., Schaanning, E., Seidel, M. and Vacirca, F. (2020),

“Interdependencies in central clearing in the EU derivatives market”, European Systemic Risk

Board Occasional Paper, forthcoming.

European Banking Authority (2020), “Interactive single rulebook”, as of April 2020.

European Central Bank (2020), “ECB announces package of temporary collateral easing

measures”, 7 April 2020.

European Central Bank/ Banking Supervision (2020), “Supervisory banking statistics”, Q4 2019.

European Commission (2020), “Economic forecasts”, Spring 2020.

European Securities and Markets Authority (2020), “Report on trends, risks and vulnerabilities”,

No 1. 2020.

European Securities and Markets Authority (2018), “EU-Wide CCP Stress Test 2017”, February

2018.

European Systemic Risk Board (2020a), “Risk dashboard”, March 2020.

European Systemic Risk Board (2020b), “Mitigating the procyclicality of margins and haircuts

in derivatives markets and securities financing transactions”, January 2020.

European Systemic Risk Board (2019), “EU non-bank financial intermediation risk monitor

2019”, July 2019.

European Systemic Risk Board (2017a), “Revision of the European Market Infrastructure

Regulation”, April 2017.

European Systemic Risk Board (2017b), “ESRB report on the macroprudential use of margins

and haircuts”, February 2017.

European Systemic Risk Board (2016a), “Macroprudential policy issues arising from low

interest rates and structural changes in the EU financial system”, November 2016.

European Systemic Risk Board (2016b), “The impact of low interest rates and ongoing

structural changes on financial markets and financial infrastructure: assessment of

vulnerabilities, systemic risks and implications for financial stability”, Technical

Documentation Section D of European Systemic Risk Board (2016a).

European Systemic Risk Board (2016c), “ESRB response to the ESMA Consultation Paper on

the clearing obligation for financial counterparties with a limited volume of activity”,

September 2016.

European Systemic Risk Board (2016d), “ESRB report to the European Commission on the

systemic risk implications of CCP interoperability arrangements”, January 2016.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

References

17

European Systemic Risk Board (2015a), “ESRB report on the efficiency of margining

requirements to limit pro-cyclicality and the need to define additional intervention capacity

in this area”, July 2015.

European Systemic Risk Board (2015b), “ESRB report on the issues to be considered in the

EMIR revision other than the efficiency of margining requirements”, July 2015.

Fache Rousová, L., Gravanis, M., Jukonis, A. and Letizia, E. (2020), “Derivatives-related liquidity

risk facing investment funds”, European Central Bank Financial Stability Review, Special

Feature B, May 2020.

Financial Stability Board (2018a), “Incentives to centrally clear over-the-counter (OTC)

derivatives, A post-implementation evaluation of the effects of the G20 financial regulatory

reforms – final report”, November 2018.

Financial Stability Board (2018b), “Analysis of central clearing interdependencies”, August

2018.

Financial Stability Board (2017), “Analysis of central clearing interdependencies”, July 2017.

Hoffmann, P., Langfield, S., Pierobon, F. and Vuillemey, G. (2019), “Who bears interest rate

risk?”, Review of Financial Studies, 32(8), pp. 2921-2954.

Huang, W. (2019a), “Central counterparty capitalization and misaligned incentives”, Bank for

International Settlements Working Paper, No 767, 11 February 2019.

Huang, W. and Takáts, E. (2020a), “Model risk at central counterparties: Is skin-in-the-game a

game changer?”, Bank for International Settlements Working Paper, No 866, 25 May 2020.

Huang, W. and Takáts, E. (2020b), “The CCP-bank nexus in the time of Covid-19”, Bank for

International Settlements Bulletin, No 13, 11 May 2020.

International Swaps and Derivatives Association (2019), “Leverage ratio treatment of client

cleared derivatives”, 16 January 2019.

Krahnen, J. P. and Pelizzon, L. (2016), “Predatory Margins and the Regulation and Supervision

of Central Counterparty Clearing Houses (CCPs)”, SAFE White Paper No 41, September 2016.

Lenoci, F. and Letizia, E. (2020), “Classifying the counterparty sector in EMIR data”, European

Central Bank Working Paper, forthcoming.

Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on

prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU)

No 648/2012 (CRR).

Roberson, M. (2018), “Cleared and uncleared margin comparison for interest rate swaps”,

April 2018.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

References

18

Rosati, S. and Vacirca, F. (2019), “Interdependencies in the euro area derivatives clearing

network: a multi-layer network approach”, European Central Bank Working Paper, No 2342,

December 2019.

Schrimpf, A., Shin, H. S. and Sushko, V. (2020), “Leverage and margin spirals in fixed income

markets during the Covid-19 crisis”, Bank for International Settlements Bulletin No 2, 2 April

2020.

Temple-West, P. (2020), “Rating agencies brace for backlash after rash of downgrades”,

Financial Times, 3 April 2020.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

19

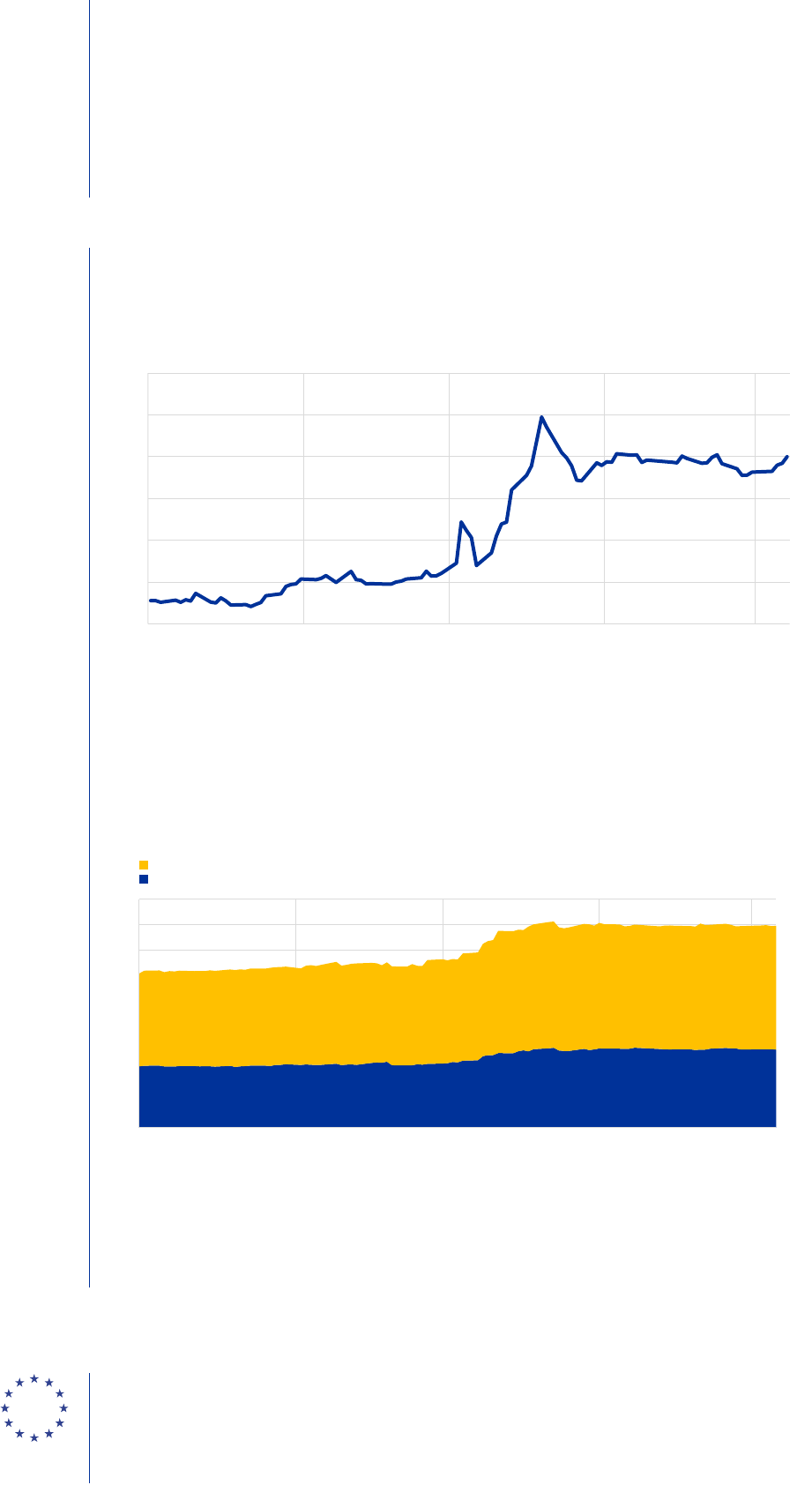

Chart A.1

Initial margins posted in European CCPs by German market participants

(19 February 2020 = 100)

Sources: EMIR data and Deutsche Bundesbank calculations.

Notes: The chart presents an equally weighted average of initial margin index (19 February 2020 = 100) across six CCPs, as

based on the initial margins pledged by German market participants to the CCPs. 19 February 2020 represents the date of the

pre-crisis peak for various equity indices (e.g. EURO STOXX 50, DAX, S&P 500) before the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. The

latest observation is for 7 May 2020.

Chart A.2

Initial margins posted by house and client accounts

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board EMIR data and ESRB Secretariat calculations based on joint work with ECB.

Note: The chart includes data for the largest four CCPs (in terms of initial margins) in the EU and United Kingdom vis-à-vis their

respective clearing members. The fraction of client initial margins is an upper bound estimate produced by combining CCP data

from the Public Quantitative Disclosure framework for Central Counterparties and (where available) EMIR data. The latest

observation is for 7 May 2020.

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

01/20 02/20 03/20 04/20 05/20

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

01/20 02/20 03/20 04/20 05/20

Client

House

Annex A: Background charts

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

20

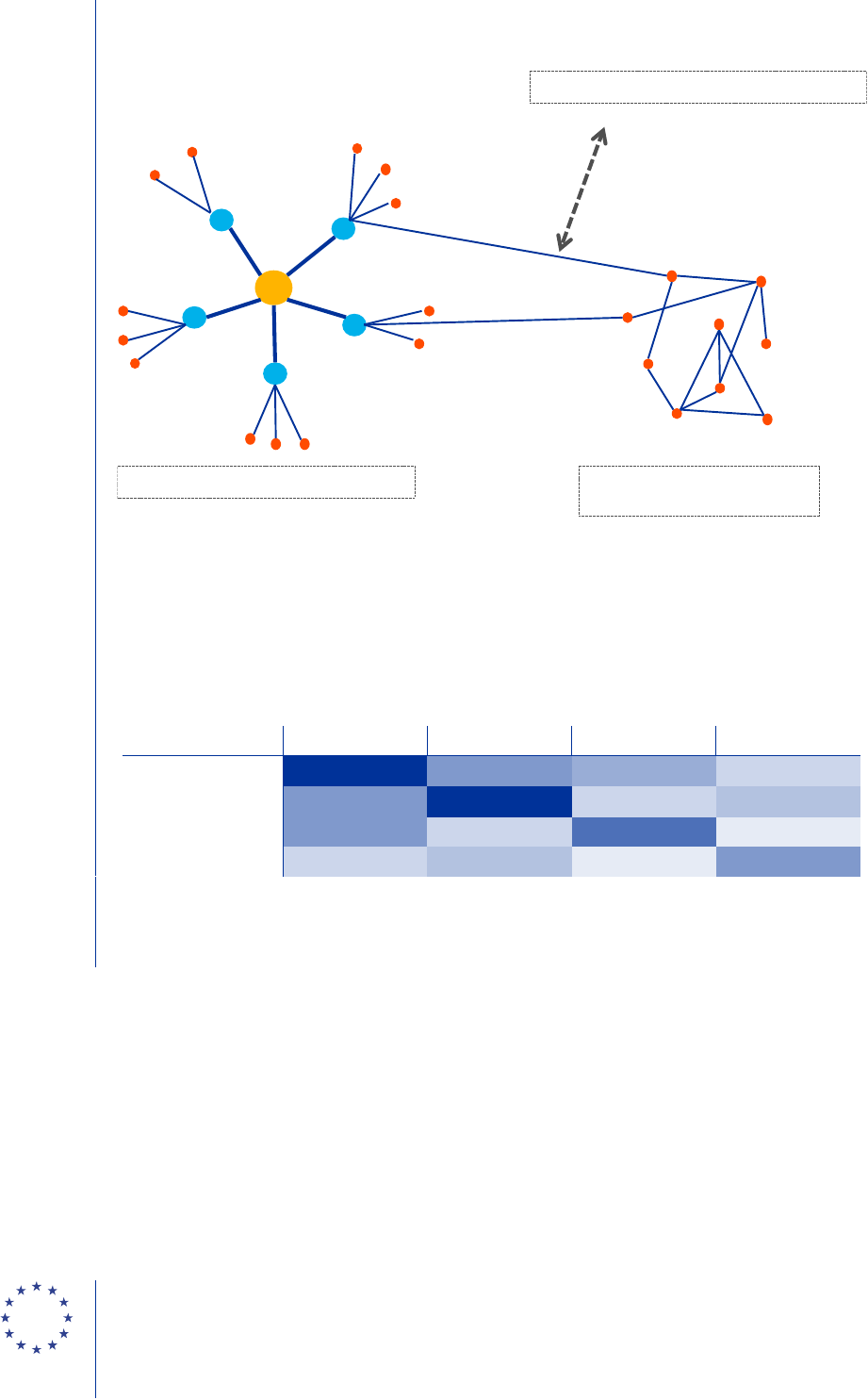

Figure A.1

Schematic overview of margining in derivative markets

Source: European Systemic Risk Board.

Note: The chart presents a schematic overview of margining interdependencies in the cleared and bilateral derivatives markets.

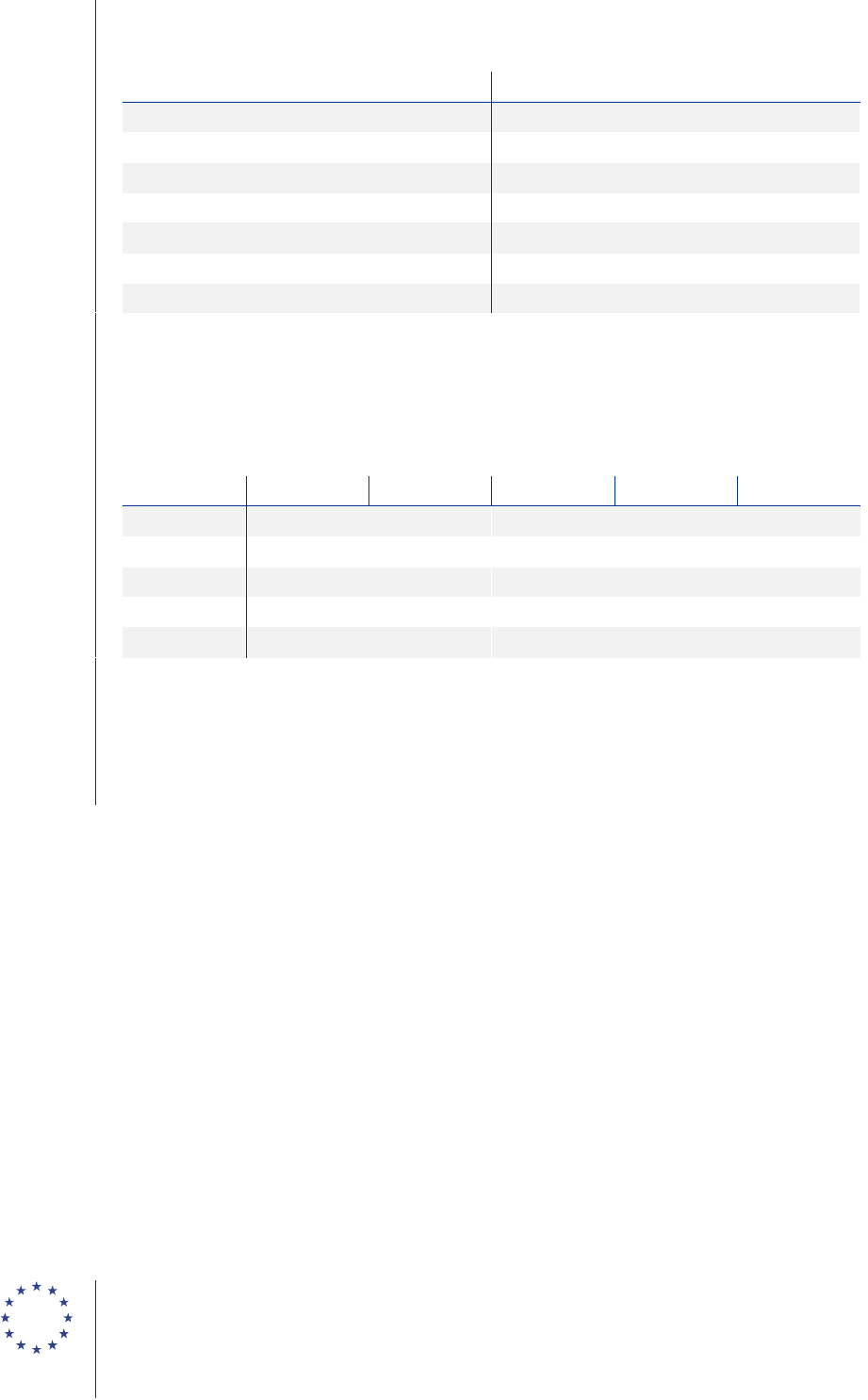

Table A.1

Interconnectedness among CCPs: number of common clearing members (CMs) on 30 March

2020

LCH Ltd Eurex Clearing AG ICE Clear Europe LCH SA

LCH Ltd

127 60 57 41

Eurex Clearing AG

60 127 42 45

ICE Clear Europe

57 42 91 35

LCH SA

41 45 35 53

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board EMIR data and ESRB Secretariat calculations based on joint work with the ECB.

Note: Number of CMs in common where the higher the number the darker the shade of blue.

Securities financing transactions

Funding of collateral

Collateral

CCP

CLEARING

MEMBER

CLIENTS

Centrally cleared derivatives

Non-centrally cleared

derivatives

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

21

Table A.2

Concentration of initial margins posted to EU and UK CCPs on 30 March 2020

Number of CMs Percentage of IM posted

Top 5

20.41%

Top 10

35.03%

Top 15

46.43%

Top 20

55.98%

Top 30

69.95%

Top 50

83.97%

Top 100

96.21%

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board EMIR data and ESRB Secretariat calculations based on joint work with the ECB.

Note: The top four EU and UK CCPs by initial margins are included in the sample, with a total of 230 clearing members.

Table A.3

Number of clearing members active in several asset classes

Interest rates Credit Currency Equity Commodities

Interest rates

189 32 32 92 59

Credit

32 17 25 20

Currency

38 25 21

Equity

708 50

Commodities

245

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board, EMIR data and ESRB Secretariat calculations.

Notes: The table shows the number of clearing members that are simultaneously active in combinations of derivative classes.

Data are as of May 2019. See El-Omari, Y., Fiedor, P., Lapschies, S., Schaanning, E., Seidel, M. and Vacirca, F. (2020),

“Interdependencies in central clearing in the EU derivatives market”, European Systemic Risk Board Occasional Paper,

forthcoming.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

22

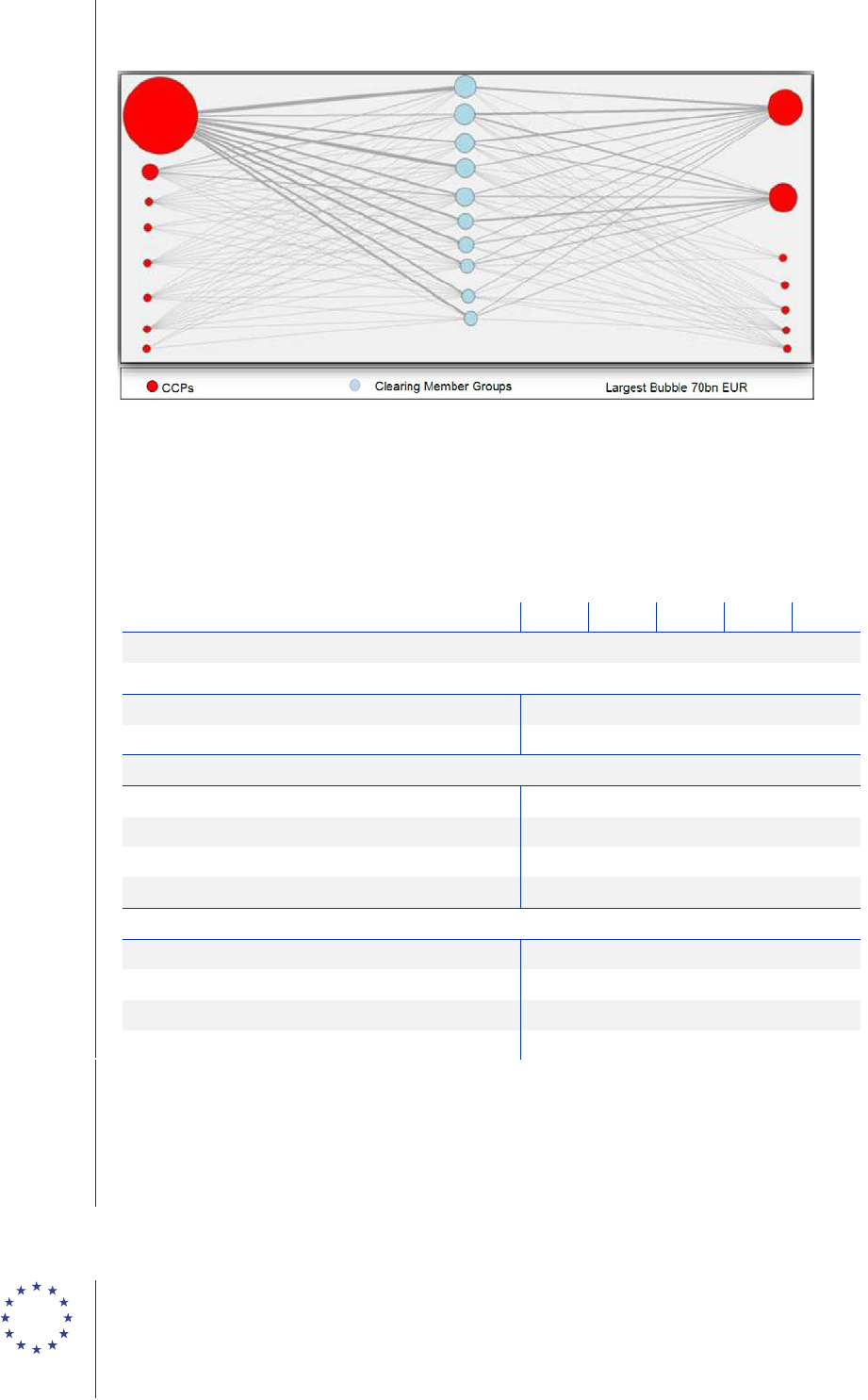

Figure A.2

Network of top 10 clearing member groups by default fund contributions and margins

Source: European Securities and Markets Authority (2018), EU-Wide CCP Stress Test 2017, February 2018, Figure 22.

Note: The results of the more recent stress test are currently under production.

Table A.4

Margins posted to CCP and available collateral of euro area (EA) banks

(EUR billions)

EA DE FR IT ES

Initial Margins posted to EU and UK CCPs by

EA clearing member banks

03/01/2020

95.58 38.363 33.792 8.613*

26/03/2020

125.058 55.039 38.934 13.389*

Bank balance sheet items

Cash, cash balances at central banks, other demand deposits

1807.1 402.2 614.4 92.3 215.5

Debt securities

2848.6 510.8 780.5 480.2 448.5

Encumbered assets

4274.6 975.8 1198.8 635.3 694.1

Unencumbered assets

17908.2 2755.9 6265.6 1811 2646.2

Value of derivatives on bank balance sheets

Derivatives – Trading (asset side)

1412.6 470.1 580.6 70.1 120.5

Derivatives – Other (asset side)

139.7 13.1 69.1 9.9 15.4

Derivatives – Trading (liabilities side)

1379.5 447 572.4 70.6 116.1

Derivatives – Other (liabilities side)

202.7 19.8 71.3 20.3 11.7

Sources: SSM supervisory banking statistics, EMIR data, ESRB Secretariat calculations.

Notes: The balance sheet data cover 113 significant euro area banks as at the end of 2019 at the highest level of consolidation.

Not all significant banks are clearing members. Balance sheet values of derivatives are reported, e.g. market values rather than

notional values. * The items on initial margins posted by IT and ES clearing member banks are shown as a sum for both

countries due to trade repository data confidentiality requirements.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

23

Table A.5a

Comparison of capital charges for credit risk for banks

Risk-weighted framework for credit risk

Risk weight Basis Legal reference

CCP exposures

Trade exposures to CCP

(margins)

2%*

Small fraction of notional amount

(Current exposure + Potential

future exposure)

CRR Art. 306

Trade exposures of CCP

members to clients

20%-150% (risk weight of the

counterparty)

Small fraction of notional amount

(Current exposure + Potential

future exposure)

CRR Art. 304

Default fund contribution

2% (theoretical limit) –

1250% (worst case scenario)

*****

Nominal amount CRR Art. 307

Other exposures under standardized approach (for comparison)

Central banks and central

governments

0%** Nominal amount CRR Art. 114

Repos (fully collateralized)

0%*** Nominal amount

CRR Art. 222, Art. 223 in

conjunction with

Art. 227CRR

Covered bonds

10-100% Nominal amount CRR Art. 129

Banks and corporates

(unsecured)

20-150% (depending on

credit quality)

Nominal amount CRR Art. 120-123

Residential mortgages

(fully secured)

35% Nominal amount CRR Art. 125

Leverage ratio framework****

Capital charge Basis Legal reference

CCP exposures

Trade exposures (margins)

3%

Small fraction of notional amount

(Current exposure net of variation

margin received + Potential future

exposure)

CRR Art. 429a

Default fund contribution

3% Nominal amount CRR Art. 429

Other exposures (for comparison)

Assets

3% Nominal amount CRR Art. 429

Repos

3%

Nominal amount +

Uncollateralized part

(counterparty risk add-on)

CRR Art. 429b

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board, EBA Interactive single rulebook, Bank for International Settlements (BIS; 2019a-e).

Note: Treatment might differ depending on specific circumstances.

* 0% if the collateral posted is bankruptcy remote in the event of the CCP or any of its members defaulting.

** Applies to exposures with highest credit quality and also to other exposures to EU central governments and central banks

denominated and funded in the domestic currency of that central government and central bank.

*** Applies to repurchase agreements (repos) with a core market participant (including inter alia central banks, banks, insurance

companies and pension funds) collateralised by exposures to central banks or central governments to which a 0% risk weight

applies and where there is no currency or maturity mismatch.

**** Binding from June 2021 onwards for EU banks.

***** Depending on the size and distribution of clearing members’ exposures and the CCP’s own funds.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

24

Table A.5b

Liquidity and funding requirements for derivatives

Framework Definition

Numerator for

derivatives

Denominator for

derivatives

Legal references

and notes

LCR

Unencumbered liquid assets

/ (Stressed outflows –

inflows)

Posted margins

decreases stock of

available unencumbered

assets

No effect, If

collateralized by high

quality liquid assets.

CRR Art. 412,

415-425

NSFR

Available stable

funding/Required stable

funding

0%

100% of derivative

assets net of VM

received minus

derivative liabilities (if

positive)

Basel III: the net

stable funding

ratio, Table 1 and

Table 2

+ 20% of derivative

liabilities (gross of VM)

In EU applicable

since June 2021

85% of initial margins

posted and

contributions to default

funds of CCPs

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board, EBA Interactive single rulebook, BIS (2019a-e).

Note: Treatment might differ depending on specific circumstances.

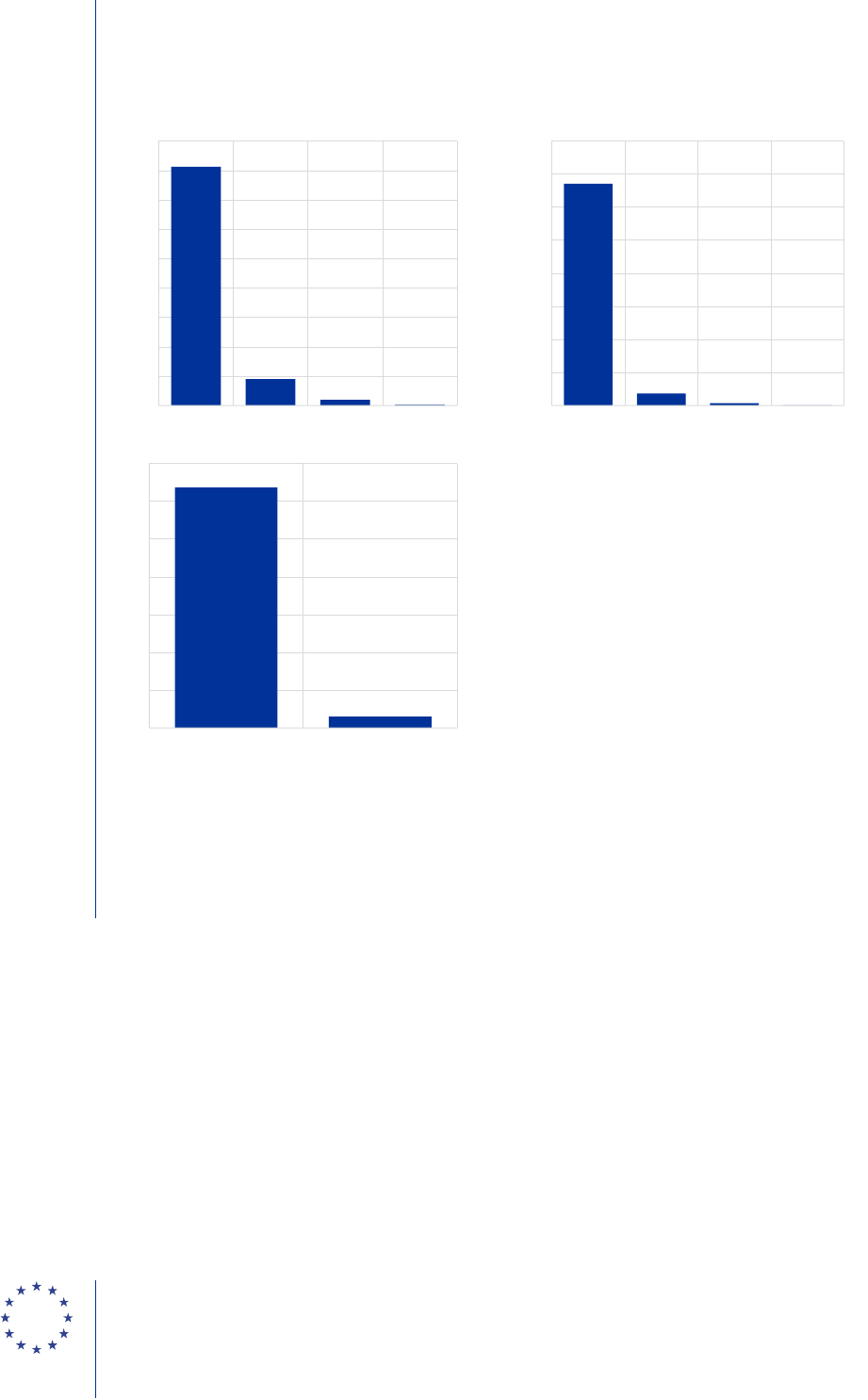

Chart A.3

Liquid asset holdings of euro area non-bank financial institutions

(left panel: percentage of highly liquid securities in total securities holdings; right panel: EUR billions)

Sources: ECB Securities Holdings Statistics and ECB calculations.

Notes: Highly liquid securities are classified according to the Basel Liquidity Coverage Ratio requirements for high-quality liquid

assets. Liquid bonds comprise Level 1 euro-denominated bonds issued by European governments and non-euro-denominated

government bonds rated at least AA.

0

200

400

600

800

1 000

1 200

1 400

1 600

Insurance

corporations

Investment funds Pension funds

Billions

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Insurance

corporations

Investment funds Pension funds

2013

2019

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

25

Chart A.4

The size and composition of variation margin calls on funds’ derivative portfolios during the

coronavirus market turmoil

(left panel: left-hand scale: EUR billions; right-hand scale: percentage points; right panel: EUR billions)

Sources: Fache Rousová, L., Gravanis, M., Jukonis, A. and Letizia, E. (2020), “Derivatives-related liquidity risk facing

investment funds”, European Central Bank Financial Stability Review, Special Feature B, May 2020, Chart B.2, as based on

EMIR data, sector classification from Lenoci and Letizia (2020), Bloomberg and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Left panel: calculated as the sum of all positive margin calls on euro area investment funds, where a positive margin call

occurs if either variation margin posted increases or variation margin received decreases from one day to another. The

classification of derivative portfolios into asset classes is based on notional amounts using an 80% threshold: if more than 80%

of the notional value of contracts in the portfolio belongs to one asset class, the portfolio is classified in this asset class. Right

panel: estimates are computed by rescaling the variation margin calls proportionally to the notional amount that they represent

for a specific asset class, in order to take into account the fact that some trades are reported as collateralised by variation

margin (in the field ‘collateralisation’ in EMIR reporting), but the size of the margin (in the fields ‘variation margins posted’ and

‘variation margin received’) is either not reported at all or not updated on a daily basis. PEPP stands for pandemic emergency

purchase programme. The latest observation is for 17 April 2020.

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

04/02 14/02 24/02 05/03 15/03 25/03 04/04 14/04

Daily variation margin calls – reported

Daily variation margin received – reported

Daily variation margin calls – full sample estimate

Daily variation margin received – full sample estimate

PEPP announced

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

04/02 14/02 24/02 05/03 15/03 25/03 04/04 14/04

Interest rate

Currency

Equity

Other

VIX (right-hand scale)

PEPP announced

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

26

Chart A.5

Margin calls, liquidity shortfalls and share of funds with shortfalls under two stress

scenarios

Scenario 1:

Extreme one-day movement

Scenario 2:

Prolonged market turmoil

Shocks on:

interest rate curves -25bps parallel shift -75bps parallel shift

USD-EUR exchange rate 2% USD depreciation 5% USD depreciation

major equity indices 5% decline 15% decline

Rationale

Shocks similar to extreme market movements observed during

September and October 2008 and March 2020

Liquidity buffer

Cash

Cash and high-quality

government bonds

Rationale

Daily variation markgins are typically required only in cash and there

could be limited possibilities for collateral transformation under

scenario 1

Netting of collateral in- and out-flows among

derivative portfolios

No Yes

Rationale

Netting of collateral inflows and outflows among derive portfolios

may not be possible under scenario 1 because the timing of

collateral in- and outflows may not coincide under scenario 1.

Instead, collateral inflows and outflows can offset each other under

scenario 2

Sources: Fache Rousová, L., Gravanis, M., Jukonis, A. and Letizia, E. (2020), “Derivatives-related liquidity risk facing

investment funds”, European Central Bank Financial Stability Review, Special Feature B, May 2020, Chart B.3, as based on

EMIR data, sector classification from Lenoci and Letizia (2020), Refinitiv and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Based on data at the end of 2018. Sample with cash and liquidity buffers includes 3,523 funds, for which liquidity buffers

are available. The full sample includes 13,969 funds, for which EMIR data indicate a holding of a derivative portfolio and

variation margin can be calculated. The rescaling to the full sample assumes that the ratio of the cash shortfall to the size of the

variation margin call is the same in the two samples. It is assumed that all derivative holdings are collateralised by variation

margin.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Sample with cash buffer Full sample estimate Sample with liq. buffer Full sample estimate

One-day movement Prolonged market turmoil

Margin call covered by buffer

Shortfall from margin call

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

27

Chart A.6

Number of dealers per client in derivatives markets

(x-axis: number of dealers; y-axis: frequency)

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board, EMIR data and ESRB Secretariat calculations.

Notes: Data are as of May 2019. See El-Omari, Y., Fiedor, P., Lapschies, S., Schaanning, E., Seidel, M. and Vacirca, F. (2020),

“Interdependencies in central clearing in the EU derivatives market”, European Systemic Risk Board Occasional Paper,

forthcoming. The upper panel shows that approximatively 8,000 clients are using a single dealer to clear interest rate derivatives

(albeit this may involve different dealers for different clients), while about 1,000 use two dealers and a negligible fraction of

clients use more than three dealers to clear their interest rate derivatives.

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

1 2 3-4 5+

a) Interest rate derivatives

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

1 2 3-4 5-10

b) Equity derivatives

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

1 2-4

c) Credit derivatives

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

28

Chart A.7

Number of clients per dealer in derivatives markets

(x-axis: number of clients; y-axis: frequency)

Sources: European Systemic Risk Board, EMIR data and ESRB Secretariat calculations.

Notes: Data are as of May 2019. See El-Omari, Y., Fiedor, P., Lapschies, S., Schaanning, E., Seidel, M. and Vacirca, F. (2020),

“Interdependencies in central clearing in the EU derivatives market”, European Systemic Risk Board Occasional Paper,

forthcoming. The upper panel shows, for instance, that there are 11 clearing members that have more than 300 clients for whom

they clear interest rate derivatives. Another 8 dealers are clearing members for between 201 and 300 clients, while 10 dealers

clear for between 101-200 clients. About 25 dealers also clear for only 1-10 clients. The ranges are established for data

confidentiality reasons.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

1-2 3-10 11-20 21-50 51-

100

101-

200

201-

300

300+

a) Number of clients per dealer – interest rate

0

5

10

15

20

25

1-2 3-5 5-10 11-50 51-

100

101-

200

201-

500

501+

b) Number of clients per dealer – equity

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

1 2-3 5-10 11-20 21+

c) Number of clients per dealer – credit

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex A: Background charts

29

Chart A.8

Repo funds rate

(percentage per annum)

Source: Repo Funds Rate.

Note: The latest observation is for 7 May 2020.

Chart A.9

Cross-currency basis swap between USD and EUR

(basis points)

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: The latest observation is for 7 May 2020.

-0.9

-0.8

-0.7

-0.6

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

03/19 06/19 09/19 12/19 03/20

RFR Spain

RFR Italy

RFR Germany

RFR France

-100

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

11/19 12/19 01/20

02/20 03/20

04/20

05/20

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex B: Background information

30

B.1: Margining types and factors behind margin developments

Variation margins (VM): Positions are marked-to-market and changes in valuations due to price

moves are exchanged on a daily basis in the form of variation margin between CCPs and other

counterparties. Higher market volatility leads mechanically to higher VM flows.

Initial margins (IM): CCPs collect collateral to cover potential future losses on a defaulting

participant’s portfolio over the period where they manage the default and reallocate the portfolio to

surviving participants (other counterparties also do so for bilateral OTC derivatives).

Intraday margin calls (IDMC): CCPs collect margins intraday, either on a business-as-usual basis

or specifically in high volatility conditions. Such margin calls cover both mark-to-market changes

(VM) and potential future losses (increases in IM). Increases in IDMCs were also observed over the

recent period of market stress.

Potential future losses have increased sharply due to the higher volatility since the outbreak

of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, initial margins increased sharply in some market

segments. This was most visible in equity and commodity markets, where volatility has been

particularly high.

17

Credit derivative markets have also seen large increases in initial margin

requirements.

18

In other markets, such as interest rate derivatives, margin increases have been

smaller due to less acute increases in volatility. There is evidence that some markets, in particular

equities, experienced significantly higher trading volumes. The increase in the size of positions was

one important factor in the increase in initial margin requirements. However, the main driver of the

increase in initial margins was the response of margin models to increased volatility and tail risks. A

number of CCPs have also increased initial margin parameters, in particular on equity instruments,

which also led to higher initial margins.

B.2: Developments in repo markets

Until now, European money market statistical reporting (MMSR) data reported by the

50 largest banks suggests that the European repo market has remained remarkably stable

during the COVID-19 crisis. Transaction volumes did not contract much, although the end-of-

quarter effect in March was slightly more pronounced. However, trading volumes with investment

funds, the second largest counterparty sector after banks, decreased quite sharply at the end of

March. As volumes recovered again – to some extent – this pattern was at least partly driven by an

end-of-quarter effect. After a temporary decrease in repo interest rates, possibly due to the ECB

17

In respect of commodities, this may be due to factors other than the COVID-19 crisis, in particular oil production decisions

and the resulting volatility.

18

In the case of credit default swaps (CDS), a part of the margin model calculation is proportional to the level of the spread.

Since spreads increased massively and remained at a higher level, this contributed to the sustained increase in initial

margin for these asset classes.

Annex B: Background information

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex B: Background information

31

intervention, rates are back to their normal levels (see also Chart A.8 in Annex A). In the bilateral

market, the proportion of repos carrying zero, negative and positive haircuts has stayed broadly

constant.

19

However, the absolute value of non-zero haircuts is becoming slightly larger (larger

positive and negative haircuts, respectively), which may indicate that market participants are

becoming slightly more risk-conscious.

While the repo market appears to be quite stable, a number of vulnerabilities are still

present. While the bulk of the transactions are cleared by CCPs, as measured by the stock

of outstanding repos, the bilateral repo market is very significant. As argued in the recent

ESRB report

20

, an increase in risk-aversion towards counterparty credit risk could result in lower

capacity or even a breakdown in this market segment. Furthermore, a significant proportion of

bilateral repos are backed by bonds issued by banks and financial institutions. Finally, there is a

tendency for banks to use collateral issued in their own country.

B.3: Concentration and client clearing

The concentration of clearing services among a few CCPs and clearing members is a well-

known issue, already clearly identified by a number of analyses carried out both at

international and European level.

21

At the global level, for some asset classes most of the

exposure in the market is concentrated among a handful of major CCPs

22

and a small number of

G-SIBS are the top clearing members in the largest CCPs. At the European level, the situation is

similar

23

even though the level of concentration seems lower; the 2018 ESMA report on the second

CCP stress test exercise shows that the top clearing member groups have simultaneous exposures

to multiple European CCPs even though “… keeping in mind the limitations of the exercise, the

interconnectedness analysis has indicated that these exposures would generally not hit

simultaneously the default fund waterfall of all these CCPs under one of the common, internally

consistent stress scenarios considered.” With regard to concentration, the analysis of the level of

concentration at individual clearing participants, assessed using the Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index

(HHI) methodology and thresholds, has not shown systemically critical concentrations at single

clearing members or groups at EU-wide level.

Current client clearing arrangements can be characterised as follows: i) they are mostly

based on Futures Industry Association documentation, but typically entail bespoke elements;

ii) initial margin requirements are typically set using internal models of the clearing member, with

CCP margin requirements as a floor; iii) counterparty-specific add-ons to those initial margin

requirements can be quite high (up to 50%); iv) collateral schedules themselves are rather strict –

typically only collateral accepted at CCPs is eligible, however, the repo desks of clearing providers

19

Under the MMSR haircuts in the CCP-cleared segment are not reported.

20

European Systemic Risk Board (2020a), Mitigating the procyclicality of margins and haircuts in derivatives markets

and securities financing transactions, January 2020.

21

Such analyses have been carried out at the international level by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and Standard-Setting

Bodies (SSBs) and at the European level by the European Securities Markets Association (ESMA) and the ESRB.

22

For example, The SWAPClear service of LCH Ltd handles approximately 80% of the amount of cleared interest rate swaps;

similarly, the ICE CCPs (US and Europe) clear the majority of CDS, both on indexes and single names.

23

See ESMA’s EU-wide CCP Stress Test 2017.

Liquidity risks arising from margin calls / June 2020

Annex B: Background information

32

typically offer (but are not contractually obliged to provide) collateral transformation services to their

clients; v) clearing providers typically have the contractual right to call for variation margin intraday,

but will normally refrain from doing so and usually pre-fund variation margins that the CCP calls

intraday; vi) the clearing member generally has the right to terminate the client clearing contract at

short notice (typically, 1-3 months, which could be longer than it would take for clients to negotiate

new contracts).

Concentration at CCPs and clearing members, combined with interconnectedness among

CCPs through common clearing members, liquidity providers, custodians or investment

counterparts, may also give rise to further cascade effects. The concentration of clearing

services at a few CCPs and in a few clearing members active in several markets is a well-known

issue, already clearly identified by a number of analyses carried out both at the international and at

the European levels, as well as being documented in this report (see Tables A.1-A.3 and Figure A.2

in Annex A). The implications of a default increase with concentration and interconnectedness.

Concentration at a CCP means that any material margin calls, non-pass-through of intraday

variation margins, changes in haircuts, etc. would affect several major entities at the same time – or

even the whole financial system. Likewise, concentration at clearing provider level means that

material changes in client clearing conditions would affect many clients at the same time, possibly

amplifying liquidity stress at the level of the market. However, the current framework for CCPs’

liquidity stress testing only accounts for interconnectedness to a very limited extent, as there is no

requirement to address concerns related to the concentration in the provision of different services

to or by the CCPs. For example, a bank can be a clearing member at one CCP, but also at the

same time play an important role at another CCP by providing liquidity to that CCP. Currently,