Department of Health and Human Services

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

http://aspe.hhs.gov

ASPE

ISSUE BRIEF

THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT:

PROMOTING BETTER HEALTH FOR WOMEN

June 14, 2016

By Adelle Simmons, Jessamy Taylor, Kenneth Finegold, Robin Yabroff, Emily Gee, and Andre Chappel

ASPE thanks the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, particularly Claudia Steiner, for their

contributions to this report.

The Affordable Care Act promotes better health for women through the law’s core tenets of access,

affordability, and quality. For example, the law’s provisions have expanded coverage through the

Health Insurance Marketplaces and Medicaid expansions; made coverage more affordable through

premium tax credits and by eliminating gender differences in premiums in the individual and small-

group insurance markets; and improved quality of coverage by eliminating lifetime and annual dollar

limits on Essential Health Benefits and requiring coverage of recommended preventive services and

maternity care. Continued implementation of the Affordable Care Act will play a significant role in

promoting the health and well-being of women across the lifespan. This report is organized into three

sections that describe how health care access, affordability, and quality of care have improved for

women since enactment of the Affordable Care Act.

ASPE Issue Brief Page 2

ASPE Office of Health Policy

Key Highlights:

Health insurance coverage increased: Between 2010 and 2015, the uninsured rate among women

ages 18 to 64 decreased from 19.3 percent to 10.8 percent, a relative reduction of 44 percent.

Coverage gains through the Marketplaces: About 12.7 million Americans selected affordable,

quality health plans through the Health Insurance Marketplaces for 2016 coverage. Of that total

number, 6.8 million (53.6 percent) are women and girls.

Preventive services at no out-of-pocket cost: Because of the Affordable Care Act, an estimated

55.6 million women with private insurance are guaranteed coverage of recommended preventive

services with no out-of-pocket costs.

Improved access to care: The percentage of women with a usual source of care has increased since

2010, particularly among young women (a 5.2 percentage point increase between 2010 and 2014),

Black women (a 5.1 percentage point increase), Hispanic women (a 6.5 percentage point increase),

and women with incomes at or below 400 percent of the federal poverty level (a 3.8 percentage point

increase).

Reductions in delayed care: From 2010 to 2014, the proportion of young women who reported

delaying or forgoing care because of cost concerns dropped by 3.4 percentage points; the proportion

dropped by 3.5 percentage points among Black women, 4.1 percentage points among Hispanic

women, and 3.0 percentage points among women with incomes at or below 400 percent of the

federal poverty level.

Protection from hospitalization costs: Women in Medicaid expansion states were much less likely

to be uninsured during a hospitalization than women in non-expansion states. The total number of

inpatient hospital discharges accounted for by uninsured women ages 19-64 declined by 50.5 percent

between 2010 and 2014 in Medicaid expansion states versus 4.0 percent in non-expansion states.

Improved outcomes for pregnant women and newborns: Babies born full-term have better

outcomes than babies who are electively delivered in the early term period. Between 2010 and 2013,

there was a 70.4 percent reduction in early elective deliveries among hospitals participating in the

HHS Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative. As of May 2014, more than 25,000 early

elective deliveries were prevented.

Better drug coverage under Medicare: More than 6 million women with Medicare prescription

drug coverage have saved $11 billion on prescription drugs since 2010.

ASPE Issue Brief Page 3

ASPE Office of Health Policy

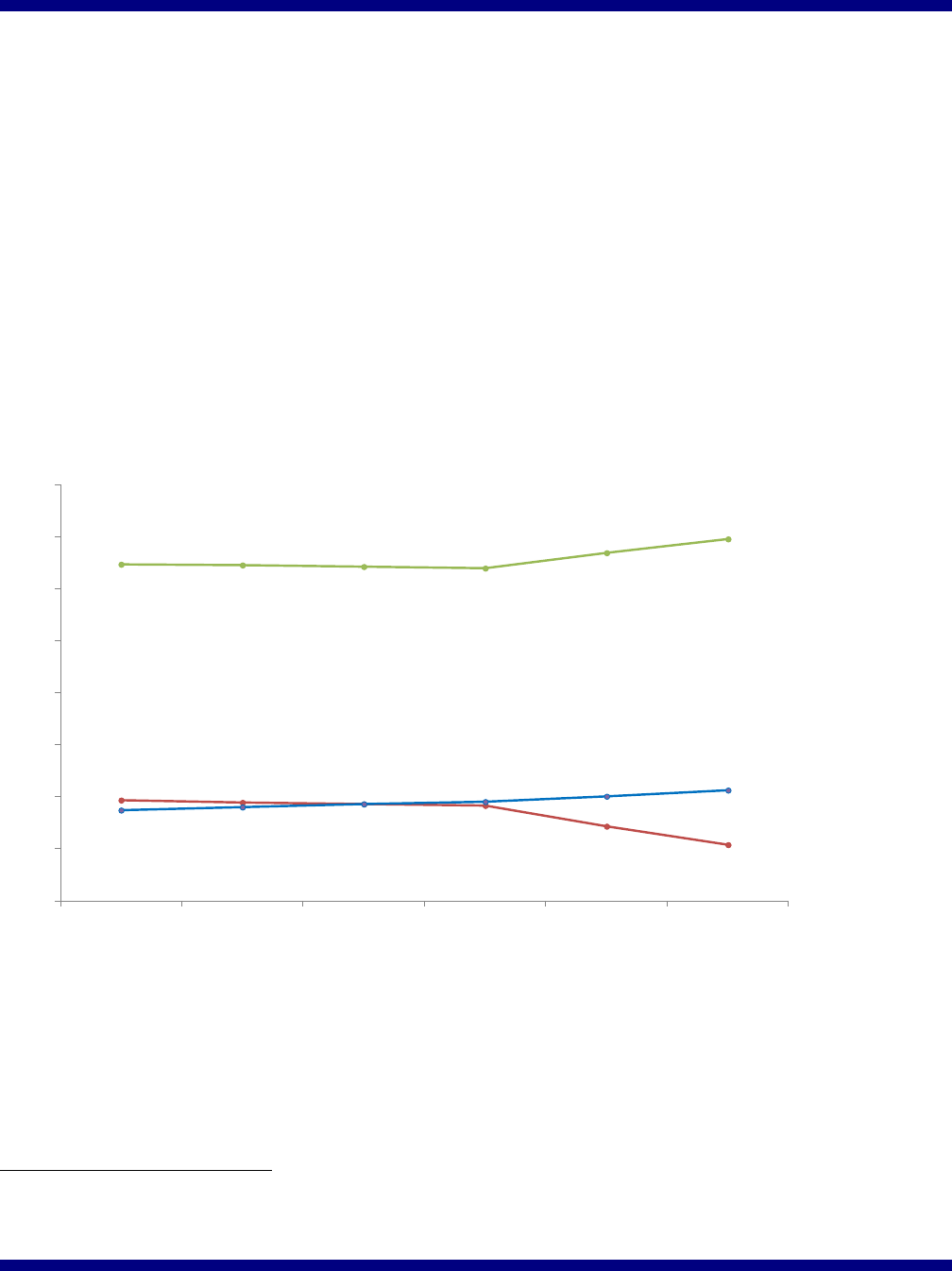

I. Improving Access to Health Insurance Coverage

In October 2013, at the start of the first (2014) open enrollment period for the Marketplaces, more than

15.9 million women ages 18 to 64 were uninsured.

1

In addition to its early coverage improvements, the

Affordable Care Act made health coverage easier to obtain through the creation of the Health Insurance

Marketplaces and the expansion of Medicaid starting in 2014. The percentage of nonelderly women

(ages 18-64) who were uninsured fell slightly from 2010 to 2013, as public coverage, including

enrollment in Medicaid, increased; see Figure 1 below. Uninsured rates among women dropped more

sharply in 2014 and 2015, with increased private coverage, including Marketplace coverage, estimated

to account for most of the gains. Between 2010 and 2015, the uninsured rate among nonelderly women

decreased from 19.3 percent to 10.8 percent for a relative reduction of 44 percent, and the share with

private coverage increased from 64.7 percent to 69.6 percent.

Figure 1: Insurance Coverage among Women ages 18-64 (2010 to 2015)

19.3%

10.8%

64.7%

69.6%

17.4%

21.2%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Private

Public

Uninsured

Notes: Ages 18-64. Sums may total more than 100% due to individuals reporting both public and private coverage.

Source: ASPE analysis of NHIS Early Release Program Data. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Health

Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Quarterly Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January 2010-

December 2015,” Table 4. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/quarterly_estimates_2010_2015_q1234.pdf

1

Estimates of the “eligible uninsured” are ASPE tabulations of nonelderly (age 0-64) uninsured U.S. citizens and others

lawfully present from the 2012 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample, adjusted to exclude estimated

undocumented persons based on imputations of immigrant legal status in ASPE's TRIM3 microsimulation model.

ASPE Issue Brief Page 4

ASPE Office of Health Policy

Health Insurance Marketplaces

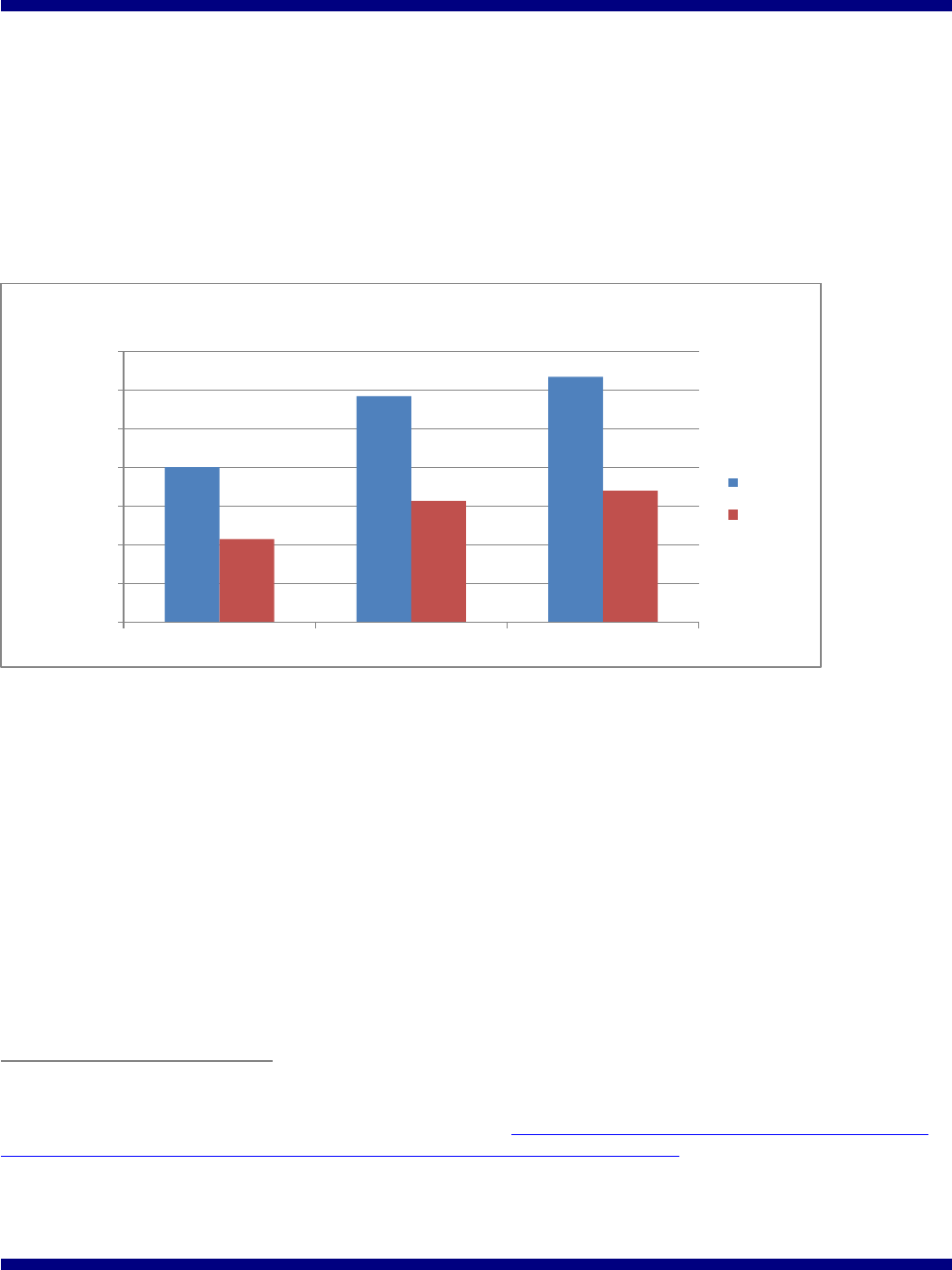

About 12.7 million Americans selected health plans for 2016 coverage through the Health Insurance

Marketplaces.

2

Of the total number who selected a Marketplace Plan during the 2016 Open Enrollment

period, 6.8 million (53.6 percent) are women and girls.

3

Figure 2 demonstrates the size of Marketplace

enrollment since 2014 and the number of women enrollees of all ages.

Figure 2: Marketplace Enrollment among Women and Girls (2014 to 2016)

Source: ASPE analysis of CMS Marketplace enrollment data.

Medicaid and CHIP

In 2014, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) served 13 percent of women

ages 19 to 64 in the U.S.

4

The Affordable Care Act improved access to Medicaid coverage in several

notable ways. Medicaid’s expansion of eligibility to low-income adults with incomes below 138 percent

of the federal poverty level has expanded access to Medicaid coverage to millions of low-income

women in the 32 states that have adopted the expansion to date, and has the potential to benefit millions

more in the states that have not yet implemented the expansion. This group includes low-income parents

and pregnant women, who otherwise lose Medicaid coverage two months following delivery of their

newborn. Coverage through Medicaid increases access to quality health care and improves the financial

security for low-income individuals.

2

This amount does not include 400,000 people who signed up on the New York and Minnesota Marketplaces for coverage

through the Basic Health Program during this Open Enrollment. HHS Fact Sheet: About 12.7 million people nationwide are

signed up for coverage during Open Enrollment. February 4, 2016. http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/02/04/fact-sheet-

about-127-million-people-nationwide-are-signed-coverage-during-open-enrollment.html#

3

Percentages are based on those who reported age/gender. The number of women presented in the graph is women and girls

of all ages. Additional information about 2016 Open Enrollment Period is available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-

insurance-marketplaces-2016-open-enrollment-period-final-enrollment-report.

4

ASPE analysis of 2014 NHIS public use data.

8,019,763

11,688,074

12,681,874

4,301,656

6,281,662

6,802,327

-

2,000,000

4,000,000

6,000,000

8,000,000

10,000,000

12,000,000

14,000,000

2014 2015 2016

Plan Selections in the Health Insurance Marketplace

Total

Women

ASPE Issue Brief Page 5

ASPE Office of Health Policy

The Affordable Care Act also amended the Medicaid statute to create a new optional eligibility group

such that states now have the option to provide family planning-related services and supplies to women

who previously only received coverage through section 1115 family planning demonstration projects.

To date, fourteen states have adopted the new family planning eligibility group.

II. Improving Affordability

Delayed or Forgone Care

Since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, fewer women report having delayed or forgone

care because of cost concerns. The proportion of young women (age 18-26) who reported delaying or

forgoing care dropped by 3.4 percentage points between 2010 and 2014; the proportion dropped by 3.5

percentage points among Black women, 4.1 percentage points among Hispanic women, and 3.0

percentage points among women with incomes at or below 400 percent of the federal poverty level

(Table 1).

5

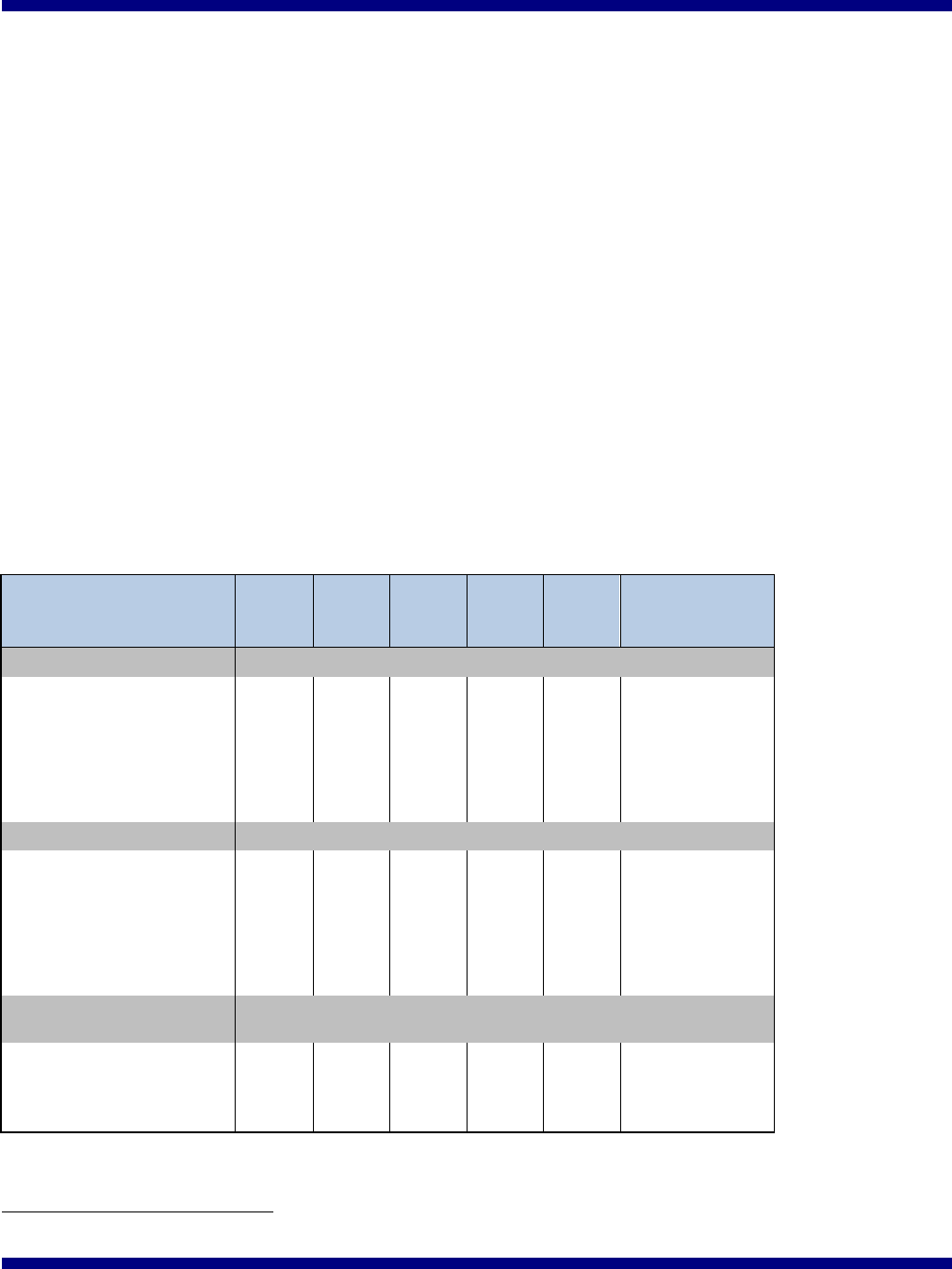

Table 1: Percentage of Women Who Had to Delay or Forgo

Care because of Cost (Weighted Percentages)

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Change

(percentage

points)

Age

18-26

15.5%

15.6%

13.3%

12.0%

12.1%

-3.4

27-39

16.6%

15.8%

15.7%

14.5%

13.9%

-2.7

40-49

16.6%

18.6%

16.7%

14.9%

14.1%

-2.5

50-64

17.2%

16.2%

16.4%

15.6%

14.1%

-3.1

65+

5.4%

5.2%

4.6%

4.6%

5.0%

-0.4

Race/ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic

13.7%

13.5%

12.9%

11.8%

11.6%

-2.1

Black, non-Hispanic

18.6%

18.3%

15.9%

16.8%

15.1%

-3.5

Hispanic

17.0%

17.2%

16.2%

14.0%

12.9%

-4.1

Asian/PI

6.8%

7.0%

7.0%

6.0%

5.5%

-1.3

Other

12.3%

14.7%

12.0%

11.5%

9.1%

-3.2

Income as % of federal

poverty level

≤400%

19.7%

19.9%

18.6%

17.5%

16.7%

-3.0

>400%

7.4%

5.9%

5.8%

4.9%

4.8%

-2.6

Missing

9.0%

10.4%

9.6%

9.5%

5.7%

-3.3

Source: ASPE analysis of NHIS 2010-2014.

5

All four trends are statistically significant (p-value<0.05).

ASPE Issue Brief Page 6

ASPE Office of Health Policy

Medicaid Expansion and Hospital Care

A particular point of financial vulnerability for women is the cost of hospital care, which is often

expensive and may not be planned. In states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act,

women were less likely to be left uninsured during a hospitalization than in states that did not expand

Medicaid.

6

The proportion of inpatient hospital discharges attributable to uninsured women in states that

expanded Medicaid dropped by 3.3 percentage points from 7.1 percent in 2010 to 3.8 percent in 2014; in

contrast, in non-expansion states, the proportion of inpatient discharges attributable to uninsured women

decreased by only 1.7 percentage points from 8.0 percent to 6.3 percent.

7

Put another way, the number

of uninsured hospitalizations in Medicaid expansion states decreased by 50.5 percent (from 381,776 in

2010 to 188,798 in 2014), while the number of uninsured hospitalizations in non-expansion states

decreased by only 4.0 percent (from 415,438 in 2010 to 398,745 in 2014).

8

This coverage trend

demonstrates the financial protections created by the Affordable Care Act, and Medicaid expansion in

particular, and helps explain why hospitals in Medicaid expansion states also have more significant

reductions in uncompensated care since passage of the Affordable Care Act than hospitals in non-

expansion states.

9

Medicare Prescription Drugs

Prior to the Affordable Care Act, Medicare Part D beneficiaries experienced a coverage gap in their

prescription drug coverage, termed the “donut hole”. The Affordable Care Act closes the donut hole

over several years until it is completely closed in 2020. Since this Affordable Care Act provision went

into effect in 2010 through 2015, beneficiaries with Medicare prescription drug coverage have saved

more than $20 billion on prescription drugs -- including savings of $11 billion for the more than 6

million women with Medicare Part D.

10

Concurrently, women with Medicare Part D note an

improvement in affordability, with a 3.8 percentage point decline in the proportion of women saying

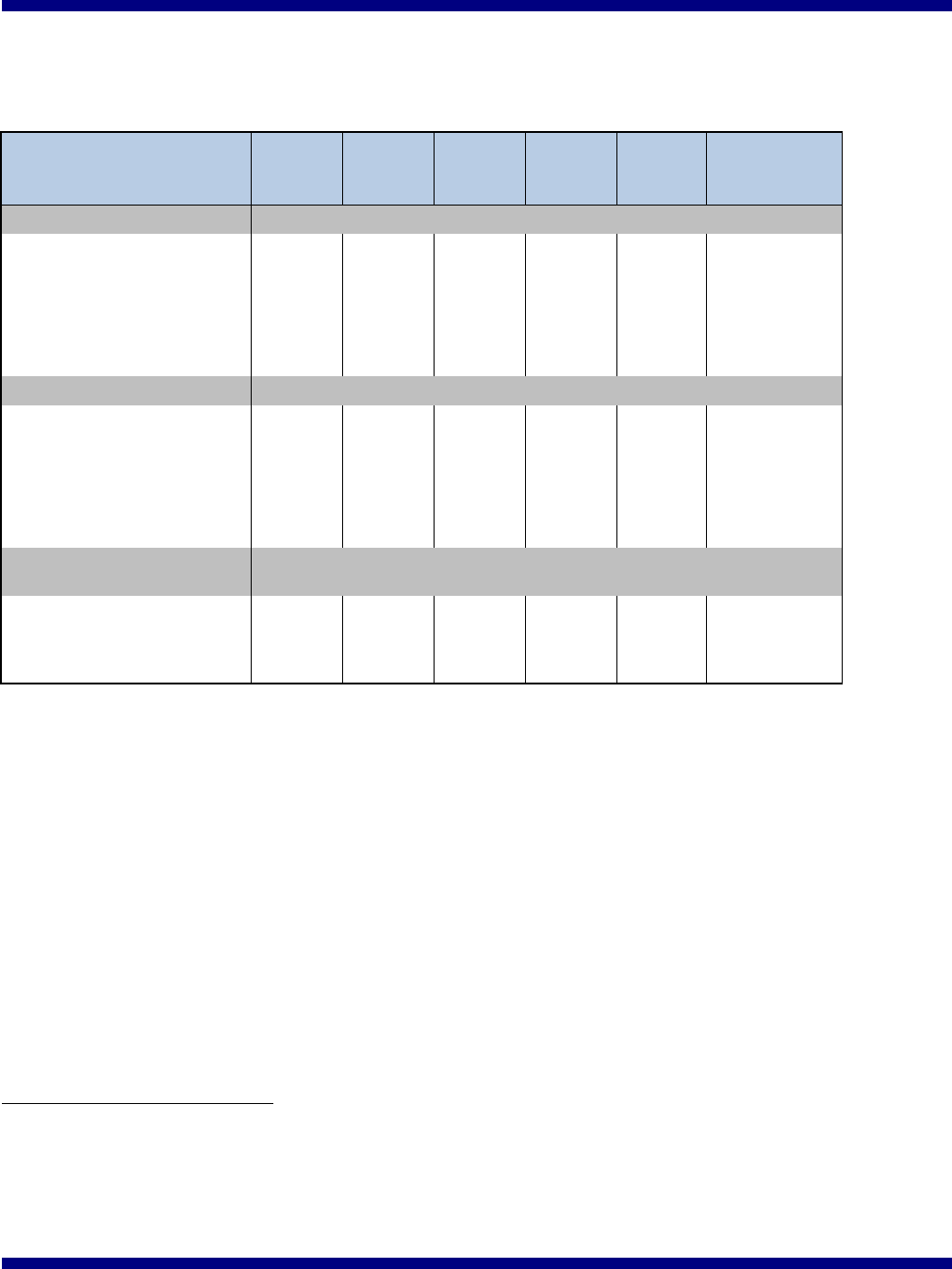

they could not afford prescription medication in the past 12 months (Table 2).

11

6

Hu, L, Kaestner, R, Mazumder, B, Miller, S, Wong, A. “The Effect of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

Medicaid Expansions on Financial Well-Being,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 22170, April 2016.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w22170.

7

AHRQ analysis of 2010 and 2014 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), State Inpatient Databases (SID) data.

For this analysis, Expansion States include AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, HI, IA, IL, KY, MD, MI, MN, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR,

RI, VT, WA, WV (n=22); Nonexpansion States include FL, GA, IN, KS, LA, MO, MT, NC, NE, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX,

VA, WI, WY (n=18). Four States (IN, LA, MT, PA) that expanded their Medicaid programs in 2015 or 2016, are considered

as Nonexpansion States for this analysis.

8

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) analysis of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), State

Inpatient Databases (SID), 2010 and 2014.

9

HHS, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2015. ASPE Issue Brief: Insurance Expansion,

Hospital Uncompensated Care, and the Affordable Care Act. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/insurance-expansion-hospital-

uncompensated-care-and-affordable-care-act

10

ASPE estimated the number of women who had Medicare Part D savings during 2010-2015 based on CMS’s estimated

total number of beneficiaries with Part D savings (https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-

releases/2016-Press-releases-items/2016-02-08.html) and the ratio of female to total non-Low Income Subsidy beneficiaries

generated from Medicare Prescription Drug Event (PDE) data.

11

This trend is statistically significant (p-value<0.001).

ASPE Issue Brief Page 7

ASPE Office of Health Policy

Table 2: Trends in Prescription Drug Affordability for Women Medicare Part D Beneficiaries,

Ages 65+, Unadjusted

2011

2012

2013

2014

Change

(percentage

points)

Prescription Drug Affordability

Skipped medication doses

6.8%

5.1%

5.1%

4.8%

-2.0

Took less Medicine

7.6%

5.1%

5.3%

4.8%

-2.8

Delayed filling a prescription to

save money

8.9%

6.7%

7.1%

6.5%

-2.4

Any limitation in prescription

drug affordability (Any Above)

10.8%

7.7%

8.5%

7.8%

-3.0

Asked your doctor for a lower

cost medication

25.6%

24.3%

21.3%

21.2%

-4.4

Bought prescription drugs from

another country

2.1%

1.1%

1.6%

1.4%

-0.7

Could not afford prescription

medication, past 12 months

10.2%

6.8%

7.2%

6.4%

-3.8

Source: ASPE Analysis of NHIS 2011-2014.

III. Improving Quality of Coverage and Health Care

Preventive Health Services

The Affordable Care Act requires most private health insurance plans to cover preventive benefits

recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the Advisory Committee on

Immunization Practices without cost-sharing. For example, since September 23, 2010, non-

grandfathered plans subject to this requirement must cover recommended services including

mammograms, screenings for cervical cancer, tobacco cessation services, and flu and pneumonia shots

without cost-sharing.

12

The Affordable Care Act also enhanced Medicare coverage of recommended

preventive services, including screening mammograms, by waiving cost-sharing (coinsurance or

deductible) that would otherwise apply. In addition, Medicare beneficiaries can now get a free Annual

Wellness Visit. The Affordable Care Act aligned Medicaid coverage for the newly eligible with that

offered by private insurance by covering the ten essential health benefits through alternative benefit plan

(ABP) coverage. This means that women covered through Medicaid expansion have access to

preventive services and other coverage similar to that offered in the private insurance market, including

access to all eighteen Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptives.

12

HHS. Preventive care benefits: Preventive health services for adults. https://www.healthcare.gov/preventive-care-benefits/

ASPE Issue Brief Page 8

ASPE Office of Health Policy

The Affordable Care Act also included a provision that took effect beginning on August 1, 2012,

requiring most insurers to cover certain additional recommended preventive health services – established

under the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines

13

– without charging a copay, coinsurance, or

deductible. Millions have gained expanded coverage of these services including contraceptive

education, counseling, methods, and services; well-woman visits; sexually-transmitted infection

counseling; Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) screening and counseling; screening for gestational

diabetes, breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling; and domestic violence screening and

counseling – all without cost sharing.

14

It is estimated that 55.6 million women with private insurance

are guaranteed coverage of recommended preventive services with no out-of-pocket costs.

15

Not having

to face the barrier of cost sharing for women’s preventive services means greater access to

recommended screenings and other services that can help protect women’s health, and access to family

planning services to help women space their pregnancies to promote optimal birth outcomes.

16

Usual Source of Care

As shown in Table 3, there have been gains in the percentage of women with a usual source of care,

particularly among young women (a 5.2 percentage point increase between 2010 and 2014), Black

women (a 5.1 percentage point increase), Hispanic women (a 6.5 percentage point increase), and women

with incomes at or below 400 percent of the federal poverty level (a 3.8 percentage point increase).

17

13

The Health Resources and Services Administration awarded a five-year cooperative agreement to the American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists to develop a collaborative process to review and recommend updates to the guidelines.

http://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/updatingwomensguidelines.html

14

HRSA. Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines. http://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/

15

HHS, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2015. ASPE Data Point: The Affordable Care Act is

Improving Access to Preventive Services for Millions of Americans. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-document/affordable-care-act-

improving-access-preventive-services-millions-americans

16

Institute of Medicine, 2011. Clinical Preventive Services for Women: Closing the Gaps.

http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2011/Clinical-Preventive-Services-for-Women-Closing-the-

Gaps.aspx#sthash.350trMBF.dpuf

17

All four trends are statistically significant (p<0.01).

ASPE Issue Brief Page 9

ASPE Office of Health Policy

Table 3: Percentage of Women with a Usual Source of Care

(weighted percentages)

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Change

(percentage

points)

Age

18-26

75.3%

77.7%

75.1%

75.5%

80.5%

5.2

27-39

81.1%

82.2%

81.3%

81.0%

83.8%

2.7

40-49

87.2%

88.1%

85.4%

87.7%

89.5%

2.3

50-64

89.4%

91.5%

89.7%

91.4%

91.9%

2.5

65+

95.8%

96.0%

95.9%

96.3%

96.7%

0.9

Race/ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic

89.1%

90.3%

88.7%

89.3%

91.1%

2.0

Black, non-Hispanic

83.0%

85.0%

83.9%

86.7%

88.1%

5.1

Hispanic

74.3%

76.3%

76.5%

77.6%

80.8%

6.5

Asian/Pacific Islander

86.8%

86.4%

84.3%

85.7%

87.4%

0.6

Other

82.0%

84.6%

82.3%

84.3%

87.5%

5.5

Income as % of federal

poverty level

≤400%

82.2%

83.1%

82.7%

82.8%

86.0%

3.8

>400%

92.5%

94.9%

92.5%

93.9%

93.8%

1.3

Missing

88.0%

89.1%

84.8%

88.2%

91.2%

3.2

Source: ASPE analysis of NHIS 2010-2014.

Maternity Care

The Affordable Care Act also funded the Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative, a

collaborative effort by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Health Resources and

Services Administration, and the Administration on Children and Families, to reduce preterm births and

improve health outcomes for newborns and pregnant women.

18

In the first stage of this initiative, sites

participating in the Partnership for Patients identified and disseminated best practices to reduce the

number of early elective deliveries among pregnant women. Between 2010 and 2013, there was a 70.4

percent reduction in early elective deliveries among participating hospitals,

19

and, as of May 2014, more

than 25,000 early elective deliveries were prevented.

20

,

21

Close to 200 sites are currently participating in

an initiative to test and evaluate enhanced prenatal care interventions for women enrolled in Medicaid or

CHIP who are at risk for having a preterm birth.

18

HHS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative: General Information.

Accessed at http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/strong-start/

19

CMS Fact Sheet (July 30, 2015). https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-

items/2015-07-30-3.html

20

March of Dimes. 2015 Annual Report. http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/2015-annual-report.pdf

21

HHS Office on Women’s Health. 2015 Report to Congress: HHS Activities to Improve Women’s Health.

ASPE Issue Brief Page 10

ASPE Office of Health Policy

As mentioned above, in addition to funding the Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative, the

Affordable Care Act amended the Medicaid program by requiring states to cover counseling and

pharmacotherapy for cessation of tobacco use by pregnant women with no cost sharing. This new

mandatory Medicaid benefit aligns with the services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force.

IV. Conclusion

Numerous provisions of the Affordable Care Act address the unique health care needs of women, and

the resulting impacts are clear through improvements in access, affordability, and quality of coverage

and care. As implementation of the Affordable Care Act continues, provisions designed to strengthen

preventive care, ensure the availability of affordable insurance coverage options, and improve health

care delivery for all Americans will continue to promote better health outcomes for women.