DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 433 595

EA 030 004

AUTHOR

Lange, Cheryl M.; Liu, Kristin Kline

TITLE

Homeschooling: Parents' Reasons for Transfer and the

Implications for Educational Policy. Research Report No. 29.

INSTITUTION

National Center on Educational Outcomes, Minneapolis, MN.

SPONS AGENCY

Special Education Programs (ED/OSERS), Washington, DC.

PUB DATE

1999-06-00

NOTE

25p.

CONTRACT

H023C50050

PUB TYPE

Reports Research (143)

EDRS PRICE

MF01/PC01 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

Elementary Secondary Education; *Home Schooling;

Nontraditional Education; Parent School Relationship;

Parents as Teachers; *School Choice; *State Surveys

IDENTIFIERS

*Minnesota

ABSTRACT

This report analyzes the reasons why parents in Minnesota

choose to homeschool their children. The survey, on which the report is

based, is part of a larger study examining each of the types of school-choice

options available in Minnesota. Three research questions guided the survey:

What are the demographic characteristics of families who choose to homeschool

their children? What are the reasons parents homeschool their children? and

To what extent is special education or the child's special needs a factor in

the homeschooling decision? Participants in the study were homeschooling

parents who had at least one kindergarten through 12th-grade child

homeschooled in 1997. The results of the survey fell into five major

categories: educational philosophy, special needs of the child, school

climate, family lifestyle and parenting philosophy, and religion and ethics.

Several subcategories within each main topic area were reviewed to understand

the parents' reasons. Parents were asked if special education or special

needs were factors in their decision to homeschool their child. Results show

that special education or the child's special needs was a factor for many

parents who homeschooled, which suggests policy implications for both

homeschooling parents and special education. Considerable variety in the

reasons reported for homeschooling was evident. (Contains 17 references.)

(RJM)

********************************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made

from the original document.

********************************************************************************

O

Research Report No. 29

Homeschooling:

Parents' Reasons for Transfer and the

Implications for Educational Policy

Cheryl M. Lange and Kristin Kline Liu

IIII II

The College of Education

& Human Development

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

Office of Educational Research and Improvement

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

This document has been reproduced as

received from the person or organization

originating it.

Minor changes have been made to

improve reproduction quality.

Points of view or opinions stated in this

document do not necessarily represent

r)

official OERI position or policy.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND

DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS

BEEN GRANTED BY

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)

1

Ear

4

Abstract

Homeschooling is one of the oldest school choice options available to parents and their

children; however, it is not often regarded as a school choice optionm,

nor has there been much

review of how the advent of school choice may be affecting homeschooling. In this

report, the

reasons parents choose to homeschool their children in Minnesota are reported. Minnesota has

some of the most comprehensive school choice options and homeschooling is one of the most

popular. The results of a survey of homeschooling parents found

reasons fall into five major

categories: Educational philosophy, special needs of the child, school climate, family lifestyle and

parenting philosophy, and religion and ethics. There were several subcategories within each main

topic area that must be reviewed to understand the parents'

reasons. In addition, parents were

asked if special education or special needs were factors'in their decision to homeschool their child.

Special education or the child's special needs was a factor for

many parents suggesting policy

implications for both homeschooling parents and special educators.

The development of this article was supported by grant number H023C50050 from the U.S.

Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. Points of view or opinions

expressed in the article are not necessarily those of the Department or Offices within it.

3

i

Research Report 29

Providing parents and their children a choice of educational options has been one of the

major reforms of the past decade. School choice has taken many forms, from open enrollment to

charter schools. One type of school choice option that has been available for many years and

growing in popularity is homeschooling. It is estimated that anywhere from 500,000 to 1,200,000

students are homeschooled in America (Ray, & Marlow, 1995; Van Gelen & Pitman, 1991).

Some researchers estimate an annual growth rate of 15%.

The homeschooling option gives parents the most freedom of any school choice option. In

educating their children at home they have control over the curriculum, schedule, training

requirements, and educational delivery.

It joins the myriad of options each providing different

levels of bureaucratic freedom. Research is currently being conducted on many of the other school

choice options documenting the reasons parents choose these options.

While in the past, homeschooling was often the only way parents could exercise control

over their child's educational delivery model, with the advent of school choice it becomes one of

many options. Does the entrée of other school choice options make homeschooling a more viable

alternative for more families, as choice in education is becoming more and more common? What

do parents tell us about their reasons for homeschooling their children? Do these reasons differ

from those cited in the current literature base?

Reasons for Homeschooling

Current review of the literature suggests there are three major reasons parents choose to

homeschool their children. Often parents choose to homeschool their children due to a

combination of these reasons. The most frequently cited reason for homeschooling is based on

spiritual or religious views (Pearson, 1996; Reinhiller & Thomas, 1996; Knowles, Muchmore &

Spaulding, 1994; Gray, 1993; Resetar, 1990; Howell, 1989; Mayberry, 1989; Groover &

Ends ley, 1988). Within this category, parents discuss how conflicts over values, curriculum, and

discipline methods shape their reasons for homeschooling (Pearson, 1996; Reinhiller & Thomas,

1996; Gray, 1993; Groover & Ends ley 1988). Other parents share a belief that their religion

1

4

Research Report 29

mandates parental responsibility for education (Ray, 1992). Still others have

a desire to control the

content of their child's education so it is consistent with spiritual

or religious beliefs. Others wish

to protect children from unwanted influences, particularly unwanted philosophies and

beliefs, or

pass on to children the family's religious or world view (Mayberry, 1989; Mayberry & Knowles,

1989).

A second major category of reasons for homeschooling currently cited

relates to the

parents' perception that the public or private school environment is harmful

to their child. Negative

peer influence, a less stressful and competition home environment, and the desire for

parents to

have primary responsibility for their child's socialization

are commonly cited reasons (Cappello,

Mullarney & Cordeiro, 1995; Knowles, 1989; Pearson, 1996; Gray, 1993;

Howell, 1989;

Mayberry, 1989: Mayberry & Knowles, 1989; Knowles, Muchmore & Spaulding,

1994; Groover

& Ends ley, 1988),.

Meeting the family's lifestyle needs constitute

a third major category of reported reasons for

homeschooling. Family unity and time together, inaccessibility and

cost of private schools, and

the special needs of an individual family

are cited as examples of family needs (Cappello et al.,

1995; Gray, 1993; Howell, 1989; Reinhiller & Thomas, 1996; Mayberry,

1989; Mayberry &

Knowles, 1989; Groover & Ends ley, 1988).

Though not cited as often as the three major categories, there

are several aspects of quality

for which parents are concerned. These include the quality of teachers,

instruction, physical

environment, school governance, and the quality of schools, in general. In addition,

parents report

concerns about inadequate academic standards and the financial status of the school

or district

(Gray, 1993; Groover & Ends ley, 1988; Knowles, 1989; Reinhiller & Thomas,

1996).

What is less understood is the role special education and special needs issues play in

parents' decision to homeschool their children. Anecdotal information

suggests that as school

choice has become more commonplace, philosophical

reasons for homeschooling have become

less paramount. Many parents report choosing the homeschooling option because their

child's

individual needs are not being met in the public

or private school. In the current literature, there is

2

5

Research Report 29

some mention of special needs as reasons for homeschooling; however, there are few recent

references and this is an area for which little is known (Knowles, Muchmore & Spaulding, 1994;

Gray, 1993; Groover & Ends ley, 1988; Ensign, 1998; Howell, 1989).

Minnesota's Experience

Minnesota was the first state to propose and pass comprehensive school choice legislation.

The first charter school opened in the state in 1991 and joined second chance options,

postsecondary options, and open enrollment in the state's menu of options. However, throughout

the past decade one of the fastest growing options in the state has been homeschooling. There

are

currently over 12,000 students who are being homeschooled in Minnesota. The University of

Minnesota's Enrollment Options Project has been investigating the various Minnesota options,

reasons parents choose them, and outcomes for students who participate in them. Little is known,

however, about reasons Minnesota parents are choosing homeschooling and how these

reasons

may or may not be different than those of parents who choose other options.

University of Minnesota researchers have also been interested in the role special education

plays in parent choice. It has been documented that students with disabilities

are participating in all

of Minnesota's school choice options and that special education reasons often motivate parents

to

choose a school other than one in their resident district (Lange and Ysseldyke, 1998). What is not

known is the role special education may play in homeschooling decisions. Often, it is assumed

that the main reason parents choose homeschooling is based on religious beliefs. Given this point

of view, educational policymakers and administrators have had little reason to question their

own

methods and educational practices and the effect they may have on homeschooling decisions.

Since much of the homeschooling research has been sponsored or published by homeschooling

advocates there is justification for a rationale that assumes religion is the principal issue in the

homeschooling decision. However, as school choice becomes more commonplace, the general

public, too, may see homeschooling, as another option by those for whom religion is not the major

factor. If this is the case, it has implications for school administrators and policymakers.

3

6

Research Report 29

With more and more parents choosing an option outside the mainstream of

education, it is

important for policymakers and educators to understand the motivation

of parents. With that

knowledge, those in the mainstream of educational delivery

can more effectively address the issues

that motivate parents to choose homeschooling

or any other option.

In this report, we present the findings from a comprehensive

survey of Minnesota parents

who homeschool their children.

Minnesota's history of school choice options provides

an

excellent environment in which to independently address the

reasons parents homeschool their

children. The state has embraced school choice options and results

may provide insight into

direction homeschooling is heading as more and more parents

are given a wide array of educational

options. Three research questions guided the

survey:

1. What are the demographic characteristics of families who choose

to homeschool

their children?

2. What are the reasons parents homeschool their children?

3. To what extent is special education or the child's special needs

a factor in the

homeschooling decision?

This study on homeschooling is part of a larger study examining each of

the types of

school choice options available in Minnesota. Analyses of charter schools in

Minnesota (Lange &

Lehr, in press) indicated that more students with disabilities

were choosing to attend charter

schools than educators or policymakers had foreseen and this situation had significant

implications

for educational policy during a time of educational reform. Therefore, the

homeschooling study

was planned to add to the knowledge base about students with disabilities and/or learning

or

behavior problems, their educational choices and the implications for policy

as well as

understanding reasons given by all parents regardless of their child's disability

status.

In order to place the homeschooling of students with special needs within

a larger context,

researchers surveyed homeschooling families with all types of students

to answer the research

questions listed above. Future reports will address specifically the differences between

parents

with and without special needs children as they relate to homeschooling. The intent of this

report

4

Research Report 29

is to describe the larger context of homeschooling in the

state and parents reasons for choosing to

homeschool.

Methods

Participants

Minnesota has over 12,000 students who receive their education through

the

homeschooling option. Participants in this study were homeschooling

parents or guardians who

had at least one kindergarten through 12th grade child homeschooled in 1997.

A stratified sample

of parents of these students were sent

surveys asking for their reasons for choosing

homeschooling, family demographic characteristics, and special education considerations.

The

population was stratified by location and the size of the school district in which they

reside. We

estimated the number of homeschooling families at 5,000 (12,000-homeschooling

students

reported to Minnesota Department of Children, Families, and Learning estimating

2.5 children per

family). We needed a sample size of approximately 350 families

to be confident in the results.

Homeschooling literature suggests that families who homeschool their children

are reluctant to

share information with official organizations. Taking this into consideration,

we oversampled

(n=740).

The state was divided into four quadrants representing the northeast, northwest,

southeast,

and southwest sections of the state. Each of these

areas is distinctive in population density and

economic development, both of which may influence homeschooling decisions. School

districts

were chosen within each quadrant based upon their proportions of special education students,

homeschooled students, school district type (rural, suburban, urban), and enrollment. School

districts from rural areas were included in the sample if they had

more than 2.5% of their student

population homeschooled. Larger districts were included if they had at least 50 students who

were

homeschooled.

5

Research Report 29

Procedures

We wanted to get as representative sample

as possible and did not want the parents'

philosophical orientation to play a role in respondent

selection. Therefore, we worked through the

school districts instead of any advocacy organization.

School districts meeting the criteria

were

contacted for approval to participate in the study. Eleven

school districts with a total of 740

homeschooling families agreed to participate in the study.

Surveys were distributed by the school district in

order to maintain privacy for the

participants and to reach as many families

as possible. Surveys were returned to the research staff

at the University of Minnesota. Surveys

were color coded so we could determine the respondents'

location according to the selected quadrant

to ensure a representative sample.

Instrument

A review of the homeschooling literature

was conducted in the fall of 1997 using the ERIC

and Psych Lit electronic databases for 1987-1997. In

addition, local and national homeschooling

websites were informally scanned to determine major

issues of relevance to homeschoolers. Based

on the review of the literature and information gleaned from the websites,

a survey was developed.

The research team and the Minnesota Survey

Research Center reviewed drafts of the

survey.

Surveys were piloted on nine families who homeschool

their children.

Data Analysis

All items were coded and analyzed descriptively.

A question on reasons parents

homeschool their children was open ended and

was coded using qualitative data analysis

techniques (Miles and Huberman, 1995). Coding

was done independently by two researchers and

compared for inter-rater reliability.

6

Research Report 29

Results

Two hundred nine of the 740 surveys sent

were returned for a return rate of 28%;

however, we reached 60% of our target goal of 350 respondents.

Eleven surveys were discarded

due to illegible answers. One hundred ninety-eight

surveys were analyzed. It should be noted that

one of our goals was to gain information about special education and homeschooling;

the

respondents may be skewed toward those with

an interest in special education issues.

What are the Demographic Characteristics of Families

Who Chose to Homeschool

Their Children?

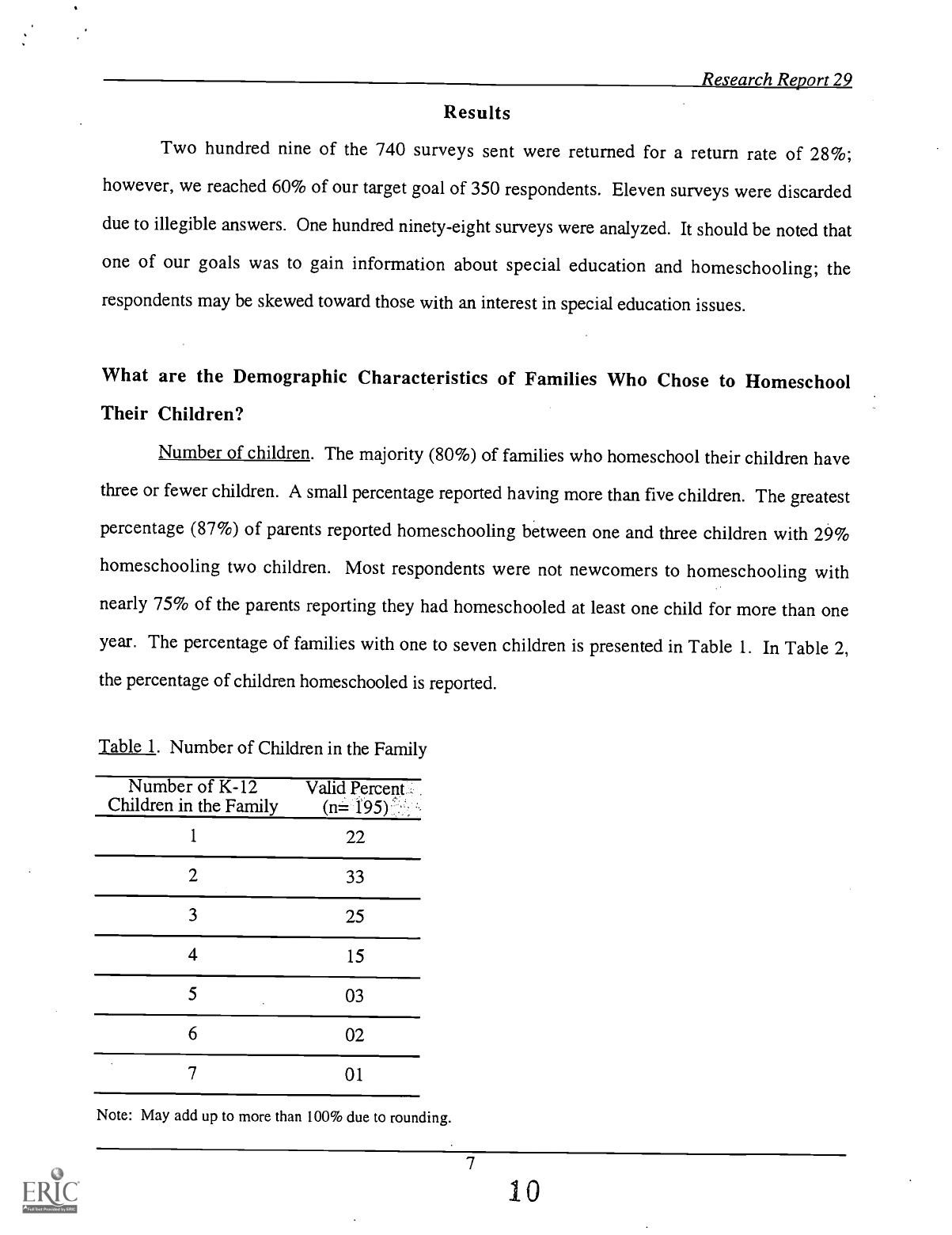

Number of children. The majority (80%) of families who homeschool

their children have

three or fewer children. A small percentage reported having

more than five children. The greatest

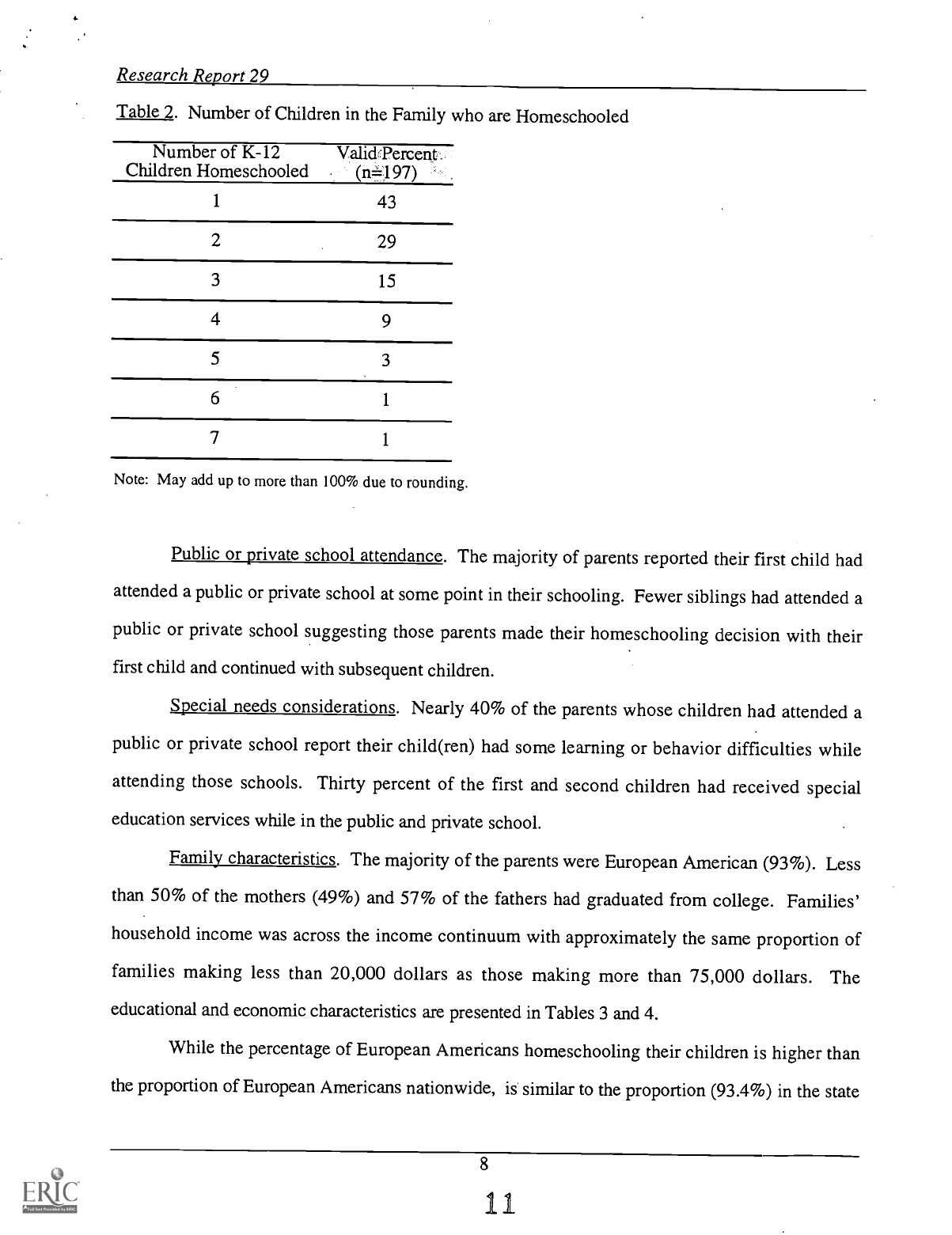

percentage (87%) of parents reported homeschooling between

one and three children with 29%

homeschooling two children. Most respondents

were not newcomers to homeschooling with

nearly 75% of the parents reporting they had homeschooled

at least one child for more than one

year. The percentage of families with one to seven children is presented in Table 1.

In Table 2,

the percentage of children homeschooled is reported.

Table 1. Number of Children in the Family

Number of K-12

Children in the Family

Valid Percent

(n=

1

22

2

33

3

25

4

15

5

03

6

02

7

01

Note: May add up to more than 100% due to rounding.

7

1 0

Research Report 29

Table 2. Number of Children in the Family who

are Homeschooled

Number of K-12

Children Homeschooled

Valid(Percent

(n-#.197)

1

43

2

29

3

15

4

9

5

3

6

1

7

1

Note: May add up to more than 100% due to rounding.

Public or private school attendance. The majority of

parents reported their first child had

attended a public or private school at

some point in their schooling. Fewer siblings had attended a

public or private school suggesting those parents made their

homeschooling decision with their

first child and continued with subsequent children.

Special needs considerations. Nearly 40% of the

parents whose children had attended a

public or private school report their child(ren) had

some learning or behavior difficulties while

attending those schools. Thirty percent of the first and second

children had received special

education services while in the public and private school.

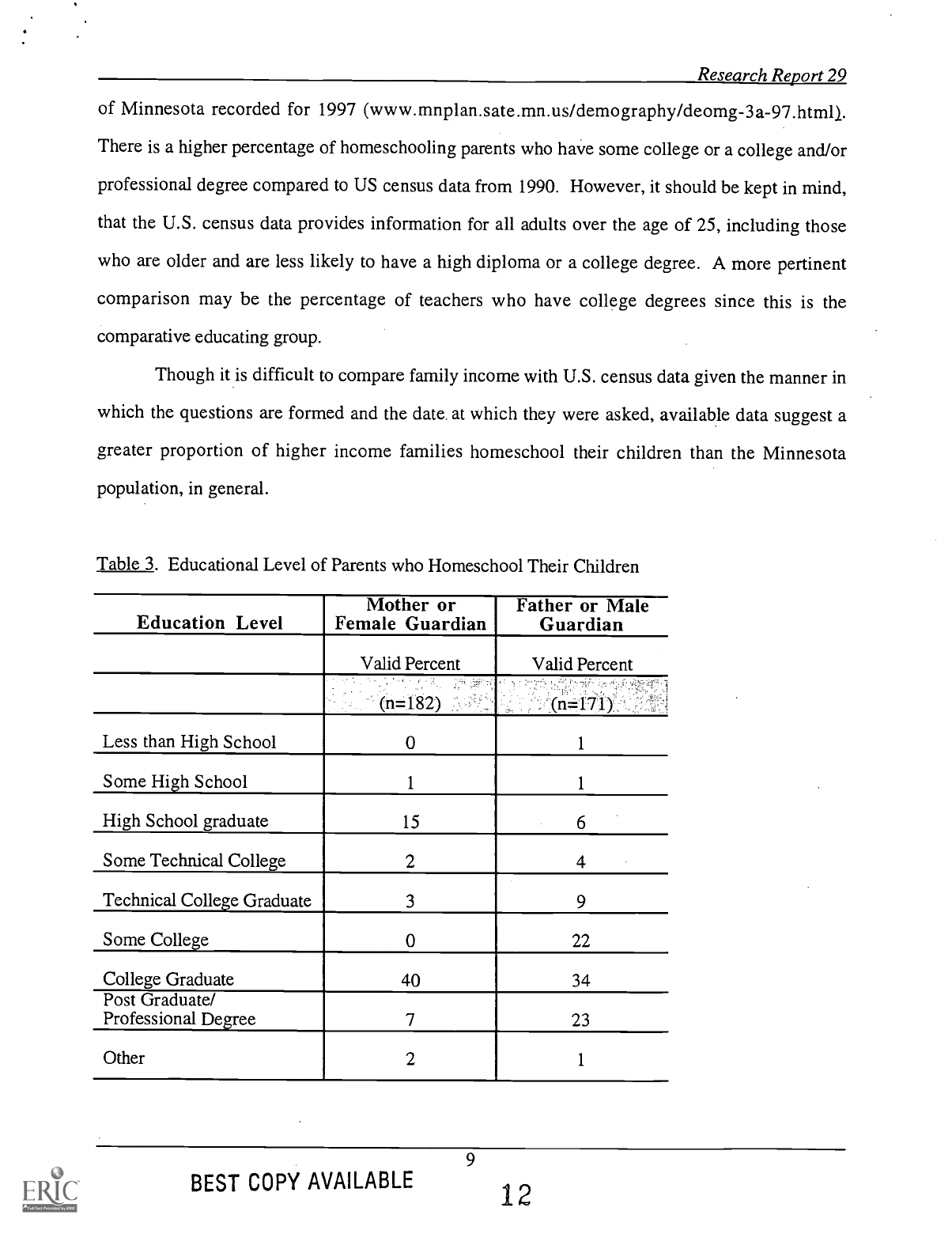

Family characteristics. The majority of the parents

were European American (93%). Less

than 50% of the mothers (49%) and 57% of the fathers had graduated

from college. Families'

household income was across the income continuum with approximately

the same proportion of

families making less than 20,000 dollars

as those making more than 75,000 dollars.

The

educational and economic characteristics

are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

While the percentage of European Americans homeschooling their

children is higher than

the proportion of European Americans nationwide, is similar

to the proportion (93.4%) in the state

Research Report 29

of Minnesota recorded for 1997 (www. mnplan. sate

.mn . us/demography/de omg -3 a-97 .htmll.

There is a higher percentage of homeschooling parents who have some college

or a college and/or

professional degree compared to US census data from 1990. However, it should be kept in mind,

that the U.S. census data provides information for all adults over the

age of 25, including those

who are older and are less likely to have a high diploma or a college degree. A

more pertinent

comparison may be the percentage of teachers who have college degrees since this is the

comparative educating group.

Though it is difficult to compare family income with U.S. census data given the

manner in

which the questions are formed and the date at which they were asked, available data

suggest a

greater proportion of higher income families homeschool their children than the Minnesota

population, in general.

Table 3. Educational Level of Parents who Homeschool Their Children

Education Level

Mother or

Female Guardian

Father or Male

Guardian

Valid Percent

Valid Percent

(n=182)

,

(n=171)

Less than High School

0

1

Some High School

1

1

High School graduate

15

6

Some Technical College

2

4

Technical College Graduate

3

9

Some College

0 22

College Graduate

40 34

Post Graduate/

Professional Degree

7 23

Other

2

1

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

9

12

Research Report 29

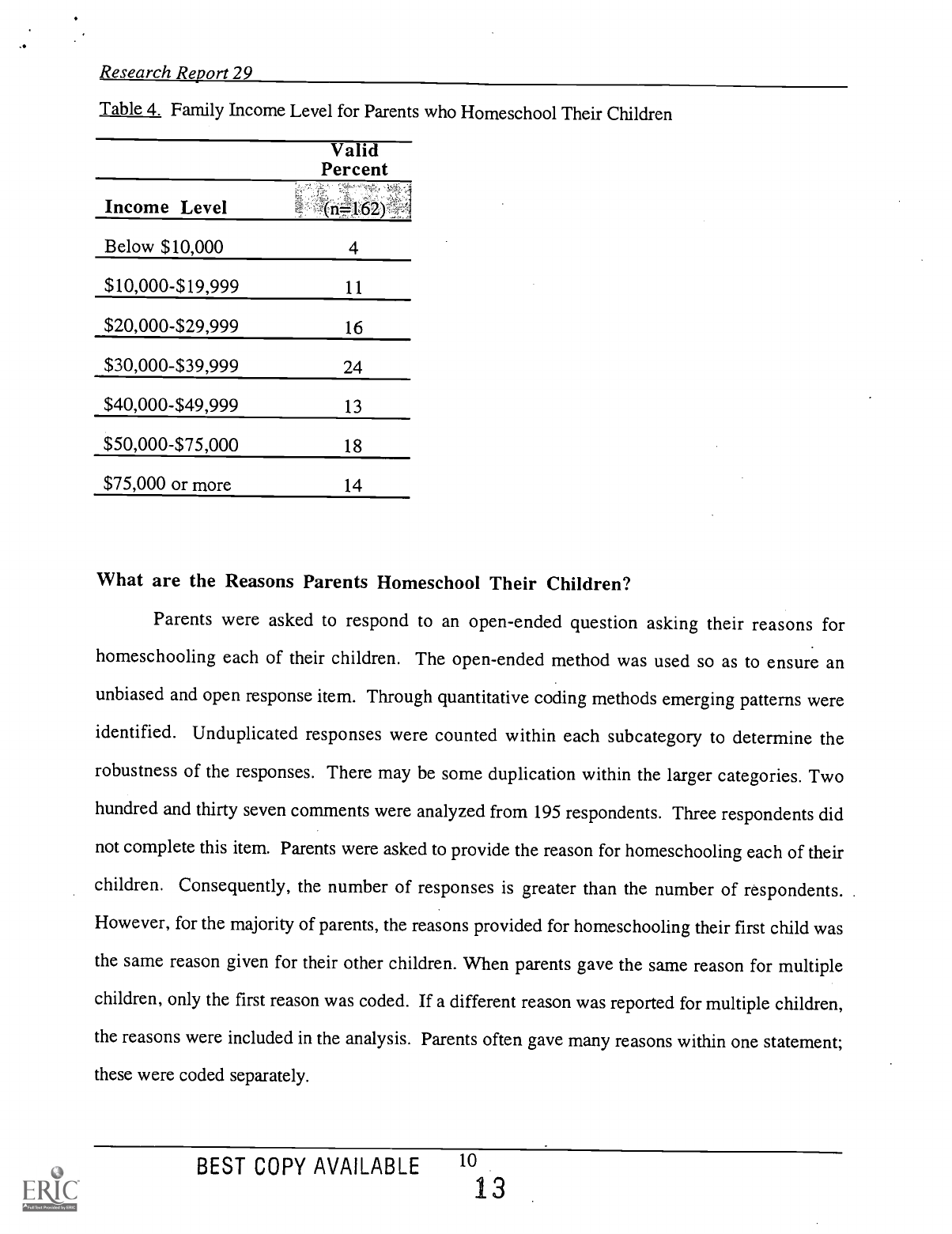

Table 4. Family Income Level for Parents who Homeschool

Their Children

Valid

Percent

Income Level

Below $10,000

4

$10,000-$19,999

11

$20,000-$29,999 16

$30,000-$39,999 24

$40,000-$49,999

13

$50,000-$75,000

18

$75,000 or more

14

What are the Reasons Parents Homeschool Their Children?

Parents were asked to respond to an open-ended question asking

their reasons for

homeschooling each of their children. The open-ended method

was used so as to ensure an

unbiased and open response item. Through quantitative coding methods

emerging patterns were

identified.

Unduplicated responses were counted within each subcategory

to determine the

robustness of the responses. There may be

some duplication within the larger categories. Two

hundred and thirty seven comments were analyzed from 195 respondents.

Three respondents did

not complete this item. Parents were asked to provide the

reason for homeschooling each of their

children. Consequently, the number of

responses is greater than the number of respondents.

However, for the majority of parents, the reasons provided for homeschooling

their first child was

the same reason given for their other children. When

parents gave the same reason for multiple

children, only the first reason was coded. If

a different reason was reported for multiple children,

the reasons were included in the analysis. Parents often

gave many reasons within one statement;

these were coded separately.

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

13

Research Report 29

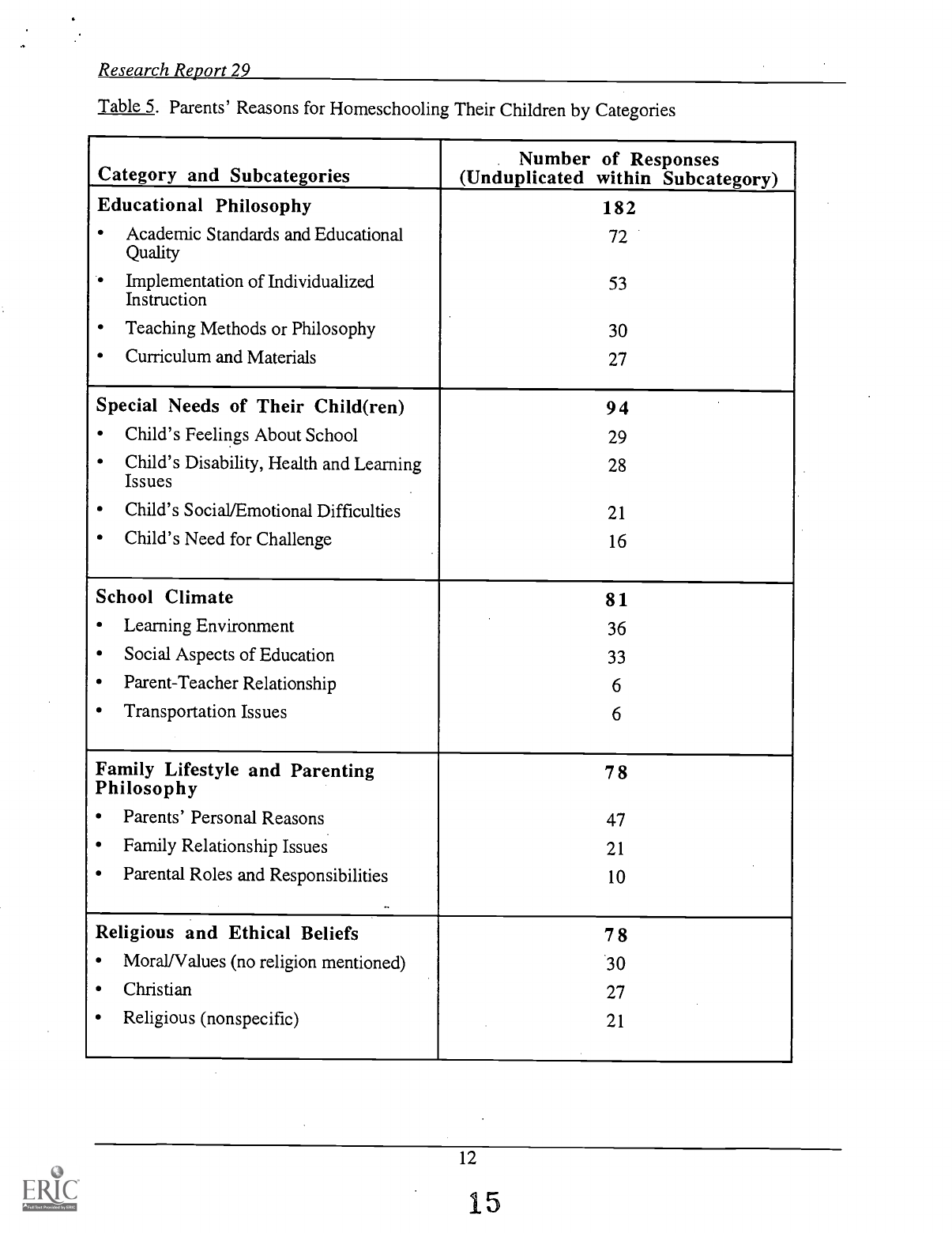

For ease of interpretation, five broad categories

were identified.

Parents' reasons for

homeschooling fall into five broad categories with several subcategories within each

one. Attention

should be paid to the subcategories within each broader category when interpreting the findings.

The broad categories include reasons related to:

Educational Philosophy;

Special Needs of the Child; and

School Climate;

Family Lifestyle and Parenting Philosophy; and

Religion and Ethics.

In Table 5, the main thematic categories and subcategories are listed with the number of

responses per category followed by examples of the reasons provided.

Although many parents noted religious and ethical reasons for educating their children at

home, a surprising number of parents report reasons that focus on other issues. Many parents

report homeschooling to meet the individual needs of their child or children or to meet the needs of

their family and their chosen lifestyles. These reasons appear to be often independent of religious

beliefs.

While there is not duplication within each subcategory, there may be duplication

among the

broad category.

There was considerable overlap as parents had multiple reasons for

homeschooling their children. This is evident in the examples of reasons presented below.

11

14

Research Report 29

Table 5. Parents' Reasons for Homeschooling Their Children by Categories

Category and Subcategories

Number of Responses

(Unduplicated within Subcategory)

Educational Philosophy

182

Academic Standards and Educational

72

Quality

Implementation of Individualized

53

Instruction

Teaching Methods or Philosophy

30

Curriculum and Materials

27

Special Needs of Their Child(ren)

9 4

Child's Feelings About School

29

Child's Disability, Health and Learning

28

Issues

Child's Social/Emotional Difficulties

21

Child's Need for Challenge

16

School Climate

81

Learning Environment

36

Social Aspects of Education

33

Parent-Teacher Relationship

6

Transportation Issues

6

Family Lifestyle and Parenting

7 8

Philosophy

Parents' Personal Reasons

47

Family Relationship Issues

21

Parental Roles and Responsibilities

10

Religious and Ethical Beliefs

7 8

Moral/Values (no religion mentioned)

30

Christian

27

Religious (nonspecific)

21

12

Educational Philosophy

Academic Standards and Quality of Education

Research Report 29

"[We wanted] to achieve academic excellence through

personalized instruction and high

standards."

"[We wanted] to provide a higher quality of education."

Individualized Instruction

"[There is] a great advantage of going at

an individual student's pace, respecting their learning

style."

"We can accommodate individual abilities easier than

can a teacher with 25-30 students."

Teaching Methods and Philosophy

[We] struggled with the methods that

were used in school. He's a hands-on learning and ten

years ago [when we started homeschooling], schools didn't teach to that style of learner."

[We] had a difference in educational philosophy than from the

norm."

Curriculum and Materials

"When we visited our public schools, their textbooks and

curriculum seemed simple and

unchallenging.

It was geared for teaching the Asian community who

were just learning

English."

"Homeschooling allows so much variety in its curriculum and

activities. The opportunities are

endless of wonderful, rich, education with

one-on-one teaching."

School Climate

Learning Environment

"Classrooms' size continue to get bigger at the local schools."

"[Child] came home every day with a headache. The teacher

was yelling constantly just to get

heard above the constant noise and talk and activities. Who

can learn anything in these kinds

of environments?"

Social Aspects of Education

"[We were] desiring to reduce the

peer influence on our children which we see as usually

negative."

"Social pressures of 5th grade drove her

crazy (boyfriends, clothes). You couldn't be

yourself; to fit in you had to be like the group."

Parent-Teacher Relationships

"We could not tolerate the rude behavior

on the part of teachers."

"Parents [are] not welcome in the classroom."

"Available teachers were not best match [with

our child]."

13

16

Research Report 29

Special Needs of Child

Child's Feelings about School

"[Our child] hated school since kindergarten; although a good student."

"[We] couldn't get our child to go to schoolwouldn't stay there when he wentwas

sometimes belligerent in class."

Child's Disability, Health and Learning Issues

"My son has ADHD and Asperger's Syndrome. The school pushed me to put him on drugs. I

did, and I couldn't stand it.

It also did not make him 'wonderful' in school."

"This child was having reading and learning difficulties that were not being diagnosed or

addressed."

"[He] has an allergic-like reaction to fluorescent lights."

Child's Social and Emotional Difficulties

"Emotional stress in class was escalated by our divorce."

"He doesn't focus easily and through the years of being in public school has continued to get

farther behind and as a result has little self-confidence. He also didn't do well socially so the

two put together were going to be disastrous."

Child's Need for Challenge

"Child needed more challenge academically."

"[There was] boredom with the traditional school; didn't feel he was learning as he could."

Family Lifestyle and Parenting Philosophy

Parent-Child Relationship

"Wanted to invest time in junior high years building relationship and encouraging study skills

and self-worth."

"Believe the parent-child relationship is the best possible context for learning-mentoring."

Parents' Personal Concerns

"I find teaching my own children is a very enjoyable addition to my daily schedule."

"Thought is fit best with our family schedule and lifestyle."

"[We homeschool] to be able to take two big, long family trips this school

year and to enhance

their academics."

Parental Roles and Responsibilities

"Homeschooling is a great way to extend your child rearing."

"We wanted to raise to raise our childrenpart of that parental responsibility is education. We

chose to do it ourselves."

14

17

Religious and Ethical

"I wanted our values to be in themnot the school systems."

"We wanted...to be able to use the Bible throughout their teachings."

Research Report 29

"[We wanted] freedom to teach her using Christian values

as a base for all subjects."

To what extent is special education

or the child's special needs a factor in the

homeschooling decision?

When parents were asked if the presence of

a learning/behavior problem or disability

entered into their decision to homeschool their child, 22% of the

respondents answer in the

affirmative for their first child. Only 9% report their child's special

needs are a factor in their

homeschooling decision for their second child suggesting that

many parents make the initial

homeschooling decision based upon the needs of their first child and continue

with the option with

the siblings. The reasons given in the open-ended item in the

survey support the strength of this

response.

Of parents who report their child has a special need, 15%

report their first child and their

second child received special services in the public

or private school prior to their homeschooling

decision. This represents 10% of the total surveyed and corresponds

to the percent of students

who receive special education in Minnesota's public schools.

Discussion

Homeschooling is another option being accessed by

many parents and students within the

United States. Minnesota is no different than

many other states in that the numbers of parents who

are choosing to homeschool are increasing each year. The reasons these parents

are choosing this

option, particularly given the context of school choice in Minnesota,

makes a review interesting

and relevant.

Minnesota parents have, perhaps, the greatest number of options available

to them through

the state's school choice option menu. Since 1989

most students have been able to apply for

enrollment in any of the state's 300 plus school districts through the

open enrollment option. In

15

18

Research Report 29

addition, junior and senior students may apply to enroll in postsecondary institutions for high

school and/or college credit at no expense to the student. Students who

are identified as at-risk for

school failure may attend one of hundreds of alternative schools designed specifically to meet their

needs or at any time enroll in a school district other than the one in their attendance

area.

Minnesota was the first state to offer parents charter schools and currently has

over 30 schools

available for students. However, within this environment of educational options, homeschooling

is one of the fastest growing options in the state.

The reasons parents give for homeschooling their children vary. The findings from this

survey affirmed the variability of homeschooling families that were found in other surveys

conducted by groups more closely tied to the homeschooling movement. As Ray (1992) pointed

out, "An attempt to homogenize home school families in order to understand them may lead a

person further from capturing the richness of many dimensions that are so much a part of the

homeschooling community (p. 4)." There was considerable variety in the

reasons reported for

homeschooling; yet, themes emerged that may have implications for educational policy in this

era

of school choice. The most frequently reported reasons for homeschooling

were in the area of

Educational Philosophy. This category was divided into four main areas: Academic standards and

educational quality; implementation of individualized instruction; teaching methods

or philosophy;

and curriculum and materials.

Many parents reported reasons related to dissatisfaction with the educational quality and

academic standards of their public schools. Parents provided examples of how the school in their

attendance area did not meet their standard of excellence. This is an interesting

reason when

viewed in the context of school choice options as most parents have the opportunity to choose

another school district through open enrollment. Minnesota has many school districts with

excellent reputations that are being accessed by students through open enrollment. Reasons

provided by open enrollment parents are similar to the academic standards reason given by

homeschooling parents; yet, homeschooling parents have chosen a different option.

16

19

Research Report 29

The other reasons cited by parents perhaps add some insight into the educational quality

reason and its implication for educational policy. Another frequently reported reason was in the

area of individualized instruction.

Findings suggest parents believe they can provide more

educational stimulation and material through the individualized instruction in the homeschooling

delivery model. If homeschooling is considered another school choice option and is one with

which school districts must compete, individualized learning plans and other educational tactics

should possibly be considered more often within the traditional school setting.

Many parents also cite other reasons related to their educational philosophy. The desire to

have more control over curriculum and materials, instructional delivery, and teaching methods

were frequently given as their reason for homeschooling. This becomes more interesting when put

in the context of school choice in Minnesota where charter schools may be formed by parents who

desire more influence in the educational philosophy of their schools. While homeschool parents

may receive some tax relief due to their homeschooling decision, charter schools enjoy public

funding at rates similar to the traditional public schools. How do school choice options such as

charter schools impact homeschooling decisions? Are more parents choosing to homeschool their

children based upon philosophical beliefs due to an educational culture within the state that

embraces parents' right to choose?

Groover, S.V. and Ends ley, R.C. (1988) summarized the implication for educational

administrators. "Rather than regarding the study of homeschoolers as irrelevant for educational

practice, early childhood educators and other educational specialists might consider this movement

as another social indicator of the health of our schools, and the practices of homeschooling parents

and the outcomes for their children as providing clues for ways to make necessary educational

reform." If homeschooling is viewed as another option rather than an anomaly, it joins the other

options in providing information that may assist educational leaders in more fully meeting the

needs of their constituency or providing data relevant to the other school choice options.

Another major category of reasons for homeschooling was Special Needs of Their Child.

This category was of particular interest since the extent to which special education or special needs

17

20

Research Report 29

motivate parents to homeschool is unknown. Parents provided

reasons in four areas: Child's

feelings about school; child's disability, health, and learning issues; child's

social/emotional

difficulties; and child's need for challenge. Each of these has implications for

educational policy

and practice.

Many parents reported their child's negative feelings about school

were such that they

affected their child's ability to perform. The parents' comments begged the question

as to what

was the etiology of the feelings. What is unknown is the extent to which parents communicated

their child's fears and sought support from the school district in dealing with the issue.

However,

the reason does support the need for exit interview

or survey information being collected by school

districts. A study of school districts that gain or lose students through

open enrollment found that

savvy school administrators often gained students regardless of educational quality issues. One of

the reasons was due to the relationship they fostered with parents and their attention

to those who

were exiting their school districts through school choice options (Lange, 1995). If school districts

want to keep their students (for funding or other reasons), it

may be useful to survey their

homeschooling parent population to learn how they could have better met their needs and the needs

of their children.

The other categories under Special Needs of Children also support this kind of relationship

building. Many parents discussed the lack of program available for their child with

a disability or

other learning need. The survey findings suggest that approximately 10% of

homeschooling

students have been served in special education. This being the

case there are implications for

special education and homeschooling. Why are parents opting out of the special education

system

and taking the responsibility themselves? What role does special education play

as a support for

homeschooling parents? Is individualized instruction

a large enough factor to influence student

performance? If so, what does this mean for the delivery of special education? In

surveys

conducted with parents who are accessing other Minnesota school choice options,

we found that

relationships were key to motivating parents and/or students to participate in the option. This

was

Research Report 29

particularly true for parents whose child had

a disability or special need (Lange & Ysseldyke,

1998).

Some parents expressed the need for

more challenge for their children. However, fewer

than expected gave this as a reason for homeschooling.

It, too, has implications for the role that

the individual student's need plays in structuring

our educational delivery system.

Do

administrators and teachers need to address

more fully the individual needs of the student and

provide for these needs? In a state such

as Minnesota, is a menu of options adequate to meeting

the individual needs of students? In other words, is that

the only avenue parents have if they desire

their child's need to be met as an individual and

not as a member of a grade level or age group?

Reasons provided by charter school and

open enrollment parents echo the sentiment that they want

their children to be viewed as individuals rather than members

of the group. The implications for

educational practice are quite profound

as it may mean a restructuring of the way students are

viewed and taught.

School Climate reasons emerged as important motivators for

homeschooling. Parents

wanted a learning environment that enhanced their child's

ability to perform, a positive social

environment, and good relationships with teachers. School

climate is becoming a bigger issue

within the educational reform debate. Providing

an environment that is conducive to learning and

respects the various learning styles is under

more and more scrutiny. Again, homeschooling

parents do not differ from many parents who

are accessing other options (Ysseldyke, Lange, &

Gorney, 1994). Does homeschooling provide just another

environment for which parents can

choose, or do school administrators need to be

more proactive in reviewing their school climate

and its effect on students and parents? If these themes

are emerging across all or many of the

options, what role do administrators have in addressing the

issues?.

Many parents also choose to homeschool their children for

reasons that are personal to their

family's lifestyle or parenting philosophies

as well as for religious reasons. Though there is a

common view that many, if not most, homeschooling parents choose

to do so because of religious

reasons, the results from this survey suggest this is one of

many reasons. Equally supported is the

19

22.

Research Report 29

notion that parents want to form a lifestyle that does not center on the traditional school calendar

or

beliefs about parenting and schooling.

Parents are homeschooling their children for many different reasons. Many of these do, in

fact, have import when discussing educational policy and practice. In the context of school choice,

homeschooling is becoming another or many options available. Reasons seem to be less focused

on religious or ethical considerations and moving more toward philosophical and educational

delivery rationales. Given this possible shift, school administrators and policymakers have

an

opportunity to review how this option if affecting their school districts and how they

can better

meet the needs of these individuals.

Limitations of the Research

Due to the uniqueness of the homeschooling population and to the circumstances

surrounding this study, there were limitations to the use of the survey findings. School districts

provided the names of homeschooling families and sent them the survey. This ensured

we were

getting a representative sample of families; however, it also meant that

we could not do the

necessary follow-up to increase our return rate and had to rely on the lists present within the school

districts. We also were aware that some parents may have negative attitudes toward the school

district and would not respond.

Since we were asking many questions about special education and special needs, we may

have gotten an inordinate number of parents who have concerns in that area. However,

we tried to

address this by having all general items at the beginning of the survey in hopes all parents would

be encouraged to complete the survey. We did use terminology that was not specific to special

education since we have found that parents are not familiar with the educational terms. This meant

we were less likely to get actual numbers of students who had been on individualized learning

programs and more likely to identify all students whose parents consider them in need of some

type of services.

Research Report 29

References

Cappello, N.M., Mullarney, P.B. and Cordeiro, P.A. (1995, April). School choice:

Four case

studies of homeschool families in Connecticut. Paper presented at the Annual Conference

of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.

Ensign, J. (1998, April). Defying the stereotypes of special education: Homeschool

students.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association,

San Diego, CA.

Gray, S. (1993). Why some parents choose to homeschool. Home School Researcher, 9

(4), 1-

12 .

Groover, S.V. and Endsley, R.C. (1988). Family environment and attitudes of homeschoolers

and non-homeschoolers (Eric Document ED 323 027).

Howell, J.R. (1989, June). Reasons for selecting homeschooling in the Chattanooga,

Tennessee

vicinity. Home School Researcher, 5 (2), 11-14.

Knowles, J.G. (1989, January). Cooperating with home school parents: A

new agenda for

public schools? Urban Education 23 (4), 392-411.

Knowles, J.G., Muchmore, J.A. and Spaulding, H.W. (1994, Spring). Home education

as an

alternative to institutionalized education. The Educational Forum, 58 (3), 238-242.

Lange, C. M. (1995). Open enrollment and its impact

on selected school districts. Unpublished

doctoral dissertation. University of Minnesota. Minneapolis, MN.

Lange, C. M. & Ysseldyke, J.E. (1998). School choice policies and practices for students with

disabilities. Exceptional Children. 64 (2), 255-270.

Mayberry, M. (1989). Home-based education in the United States: Demographics, motivations

and educational implications. Educational Review, 41 (2), 171-180.

Mayberry, M. and Knowles, J.G. (1989). Family unity objectives of

parents who teach their

children: Ideological and pedagogical orientations to home schooling. The Urban Review,

21 (4), 209-225.

21

24

Research Report 29

Pearson, R. (1996). Homeschooling: What educators should know. (ERIC document ED 402

135).

Ray, B.D. (1997). Strengths of their own. Salem, OR: National Home Education Research

Institute (NHERI) Publications.

Ray, B.D. (1992). Marching to the beat of their own drum. Paeonian Springs, VA: Home

School Legal Defense Association.

Reinhiller, N. and Thomas, G.J. (1996). Special education and homeschooling: How laws

interact with practice. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 15 (4), 11-17.

Resetar, M.A. (1990, June). An exploratory study of the rationales parents have for

homeschooling. Home School Researcher 6 (2), 1-7.

Ysseldyke, J. E., Lange, C. M., & Gorney, D. (1994). Parents of students with disabilities and

open enrollment: Characteristics and reasons for transfer. Exceptional Children, 60 (4),

359-372.

U.S. Department of Education

Office of Educational Research and Improvement (OERI)

National Library of Education (NLE)

Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC)

REPRODUCTION RELEASE

(Specific Document)

I. DOCUMENT IDENTIFICATION:

0

ERIC

AERA

Title:

Iftmeschooli

v

o

6crenisi lezetts

--71761A,,,,90.4-

44(a

toapkeemons Firtttr

e,

1 ne___

tA_

Author(s):

r

the

Corporate Source:

Enrol rnevot-calimits Pnyd--

eoik9e. o-F Ed

0 u444Avi.

a,

rY)

II..-REPRODUCTION RELEASE:

Publication Date:

Katy+

3-u,11e,

lq q

In order to disseminate as widely as possible timely and significant materials of interest to

the educational community, documents announced in the

monthly abstract journal of the ERIC system, Resources In Education (RIE), are usually

made available to users in microfiche, reproduced paper copy,

and electronic media, and sold through the ERIC Document Reproduction Service

(EDRS). Credit is given to the source of each document, and, If

reproduction release is granted, one of the following notices is affixed to the document.

If permission is granted to reproduce and disseminate the identified document, please

CHECK ONE of the following three options and sign at the bottom

of the page.

The sample slicker shown below will be

The sample slicker shown below wit be

The sample sticker shown below will be

affixed to all Level 1 documents

affixed to all Level 2A documents

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND

DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS

BEEN GRANTED BY

\e

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)

Level 'I

Check here for Level 1 release, permitting reproduction

and dissemination In microfiche or other ERIC archival

media (e.g., electronic) and paper copy.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND

DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL IN

MICROFICHE, AND IN ELECTRONIC MEDIA

FOR ERIC COLLECTION SUBSCRIBERS ONLY,

HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

\e

Sa

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)

2A

Level 2A

E

Check here for Level 2A release, permitting reproduction

and dissemination in microfiche and in electronic media

for ERIC archival collection subscribers only

affixed to all Level 28 documents

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND

DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL IN

MICROFICHE ONLY HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

2B

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)

Level 2B

Check here for Level 28 release, permitting

reproduction and dissemination In microfiche only

Documents will be processed as Indicated provided reproduction quality permits.

If permission to reproduce Is granted, but no box is checked, documents will be processed at Level 1.

I hereby grant to the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) nonexclusive

permission to reproduce and disseminate this document

as indicated above. Reproductidn from the ERIC microfiche or electronic

media by persons other than ERIC employees and Its system

contractors requires permission from the copyright holder. Exception is made for nonprofit reproduction

by libraries and other service agencies

to satisfy information needs of educators in response to discrete inquiries.

I AtisSfLt

here,-)

Sign

please °ManizatimIlici

nta)

6740611/a

Piveried. A4

i

cgi,c"

Printed NanelPositioNTille

a he-of

LI LAX

Zecir-e-'626-956

E

I Address:

e-49

,P6

ge,w-idt)/ar-ia d

F%ed

6 act--o pa9

Date: 1f-7

(over)

III. DOCUMENT AVAILABILITY INFORMATION (FROM NON-ERIC SOURCE):

If permission to reproduce is not granted to ERIC, or, if you wish ERIC to cite the availability of the document from another source, please

provide the following information regarding the availability of the document. (ERIC will not announce a document unless It is publicly

available, and a dependable source can be specified. Contributors should also be aware that ERIC selection criteria are significantly more

stringent for documents that cannot be made available through EDRS.)

Publisher/Distributor:

Address:

Price:

IV. REFERRAL OF ERIC TO COPYRIGHT/REPRODUCTION RIGHTS HOLDER:

If the right to grant this reproduction release is held by someone other than the addressee, please provide the appropriate name and

address:

Name:

Address:

V. WHERE TO SEND THIS FORM:

Send this form to the following ERIC Clearionhouse,:_

1111;

uNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND

ERIC CLEARINGHOUSE ON ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION

1129 SHRIVER LAB, CAMPUS DRIVE

COLLEGE PARK, MD 20742-5701

Attn: Acquisitions

However, if solicited by the ERIC Facility, or if making an unsolicited contribution to ERIC, return this form (and the document being

contributed) to:

ERIC Processing and Reference Facility

1100 West Street, 2nd Floor

Laurel, Maryland 20707-3598

Telephone: 301-4974080

Toll Free: 800-799-3742

FAX: 301. 953 -0263

e-mall: [email protected]

WWW: http://ericfac.piccard.csc.com

EFF-088 (Rev. 9/97)

PREVIOUS VERSIONS OF THIS FORM ARE OBSOLETE.