Marks-Hirschfeld Museum

of Medical History

April 2021

Curator’s Introduction

Dear Readers,

My guess is that many of you have donned a pair of specs to read this newsletter, if you weren’t

wearing them already. In this edition, Robert narrates the evolution of spectacles, from the concave

emerald that Nero employed to watch gladiatorial fights to the classy frames and thin lenses we

know today. The changes that glasses enabled for industry and the relationship between glasses and

literacy are particularly interesting.

Like Robert, Jan Nixon is another of the Museum’s long-serving volunteers. She has been working

diligently on our photographic collection, including sorting through our large archive of historical

images from the Faculty. Jan’s contribution to this edition of the newsletter is a closer look at the

medical school’s second year class photographs from years 1937 and 1942. See if you recognise any of

the names!

Finally, in the next fortnight we will be emailing a short audience survey which I urge you to complete.

We are hoping to gain a better understanding of what you look for in a newsletter, to ensure we are

providing relevant, interesting and anticipated content in a format that is easy to enjoy. After all,

where would we be without our readers!

Until I write again, take care.

Charla Strelan

Curator, Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 2

Eyes have always fascinated humans. They

acquired metaphysical properties in antiquity,

from” The Eye of Horus” which was used by

ancient Egyptians to protect its wearer from evil,

to classical Greek mythology which related how

seeing the mythical gorgon’s face meant being

turned to stone. Vision is central to awareness

and consciousness. Modern neurophysiology

shows that the optical cortex has many

connections throughout the cerebral cortex

to explain the deep integration of vision into

emotions, memory, sensations and language.

Poor vision aects many humans, so it is

unsurprising to find that there have been

frequent attempts to improve human vision

across history. Whilst myopia or short

sightedness arises in childhood, presbyopia or

the diminishing ability to focus on objects at

close range aects us all in our fifth decade.

As the development of reading and writing in

the classical periods of both Asia and Europe

progressed, so to did vision related problems

and the need for corrective lenses. References

in texts are sparse which makes it dicult to

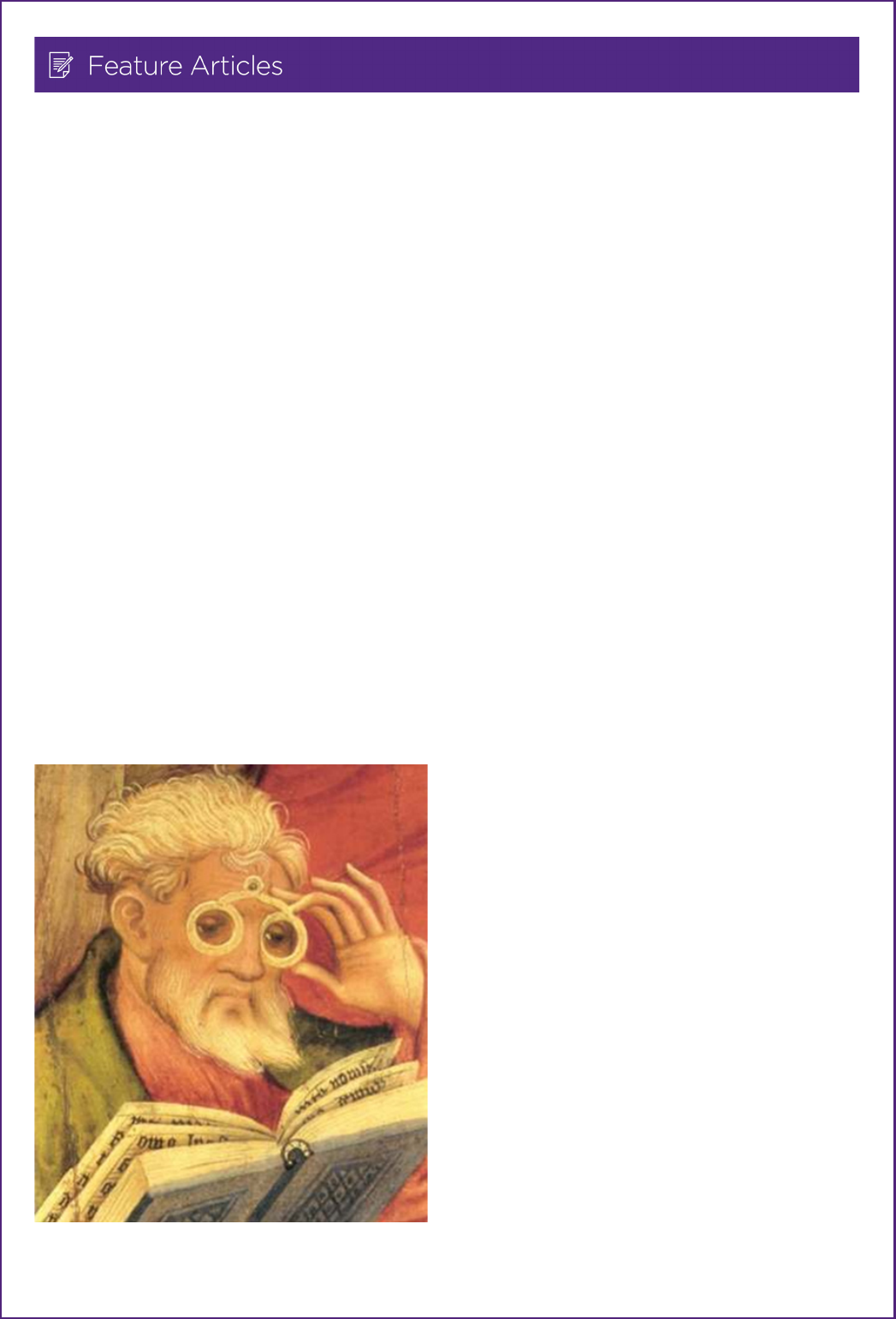

Glasses Apostle by Conrad von Soest from Bad Willungen

(wikimedia.org: Conrad von Soest)

Eyes and Glasses: Robert Craig, MHMH Volunteer

trace the development of spectacles. Claims

have been made around the world from China,

India, Africa, Arabia and southern Europe

though they are often found to be erroneous

or added later to ancient texts to establish

precedence. It is likely that spherical clear

quartz stones obtained magnification for

wealthy Egyptians in pharaonic times and

Emperor Nero was said to use an emerald to

see better in 60 CE. Protective eye covers were

recorded in China and Inuit used them to reduce

snow blindness. Widespread use of magnifying

tablets and stones by scribes and monks was

found in the twelfth century but the lack of

understanding of the behaviour of light on

reflective and translucent surfaces prevented

consistent progress. The Byzantine philosopher

and mathematician Ptolemy (100-170 CE)

studied optics and recognised magnification

was obtained by looking through transparent

spheres and spherical flasks filled with water

but he did not master the laws determining

reflection, refraction or chromatic aberration.

His written accounts travelled East and were

used by Islamic scholars, including Alhazen in

his Book of Optics ca. 1021. It seems likely that

the origins of modern spectacles are first to be

found in thirteenth century Italy. Records from

Venice (especially from Murano) suggest that

the glass makers’ skill allowed them to make

spheres accurately and magnifying convex

lenses quickly followed. Whether these were

made by blowing a hollow flask and using a

section of it as a lens or by cutting the lens

from a block or bisecting a solid sphere and

then grinding and polishing with serially finer

abrasives is unknown because the glass makers’

techniques were kept secret and were strongly

controlled by their guild to create a monopoly

for such valuable inventions. It is likely that

all these methods were used. Giordano of

Pisa wrote in 1306 of it being not 20 years

since eyeglasses had been made but the idea

of joining two lenses into a frame to make

spectacles took time. The earliest examples of

rivet spectacles were found in Celle in Germany

dating from 1400 and the first spectacle shop

opened in Strasbourg in 1466. Trade in lenses

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 3

was extensive and widespread by this time and

included a shipment of 24,000 Italian glasses

found in Turkey dating from the early 1500s. These

predated the earliest authenticated pictures and

references in China or India.

The renaissance, the enlightenment and the

demands of industrialisation accelerated

the process and success was rewarded with

improved eciency, advances in scholarship and

prolongation of the working life of artisans. The

invention of the printing press in 1456 was pivotal

in eyeglass history and improved lamp-making

extended the working day. With the widespread

printing of books, the use of reading glasses

began trickling down through the ranks of society.

However, it was not until 1620s in Spain that the

problems of making graded lenses were overcome,

allowing the prescriber to test the eyes and match

the lens required. The study of optics and technical

advance has resulted in improvement and demand

for visual aids into the 21st century.

It took until ca 1750 for Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

in the Netherlands (1632-1723) to make the first

compound microscope. He used both hollow

and solid spherical lenses as the objectives,

but he had to make them himself to enable

him to be the first to see various microbes

and cells. Roger Bacon knew about concave

lenses for myopia in 1262 but an explanation

was not forthcoming until Johannes Kepler

(1571-1630), more famous for his astrological

discoveries and elucidating the laws of planetary

motion, published his work in 1604 on optics,

Astronomiae Pars Optica, though his interest

in vision was secondary to astrology and

astronomy. He outlined the laws governing the

behaviour of light, reflection and the principle of

a pinhole camera but the law of refraction was

absent from his work. Cylindrical lenses used for

strabismus were not designed until 1825 when

they may have been introduced by George

Airy a British astronomer contemporaneously

with John McAllister in Philadelphia. Benjamin

Franklin (1706-1790) is said to have introduced

bifocals by using half-moons of convex and

concave lenses to correct his myopia and

presbyopia but this was probably an English

invention by Samuel Price in 1775. However,

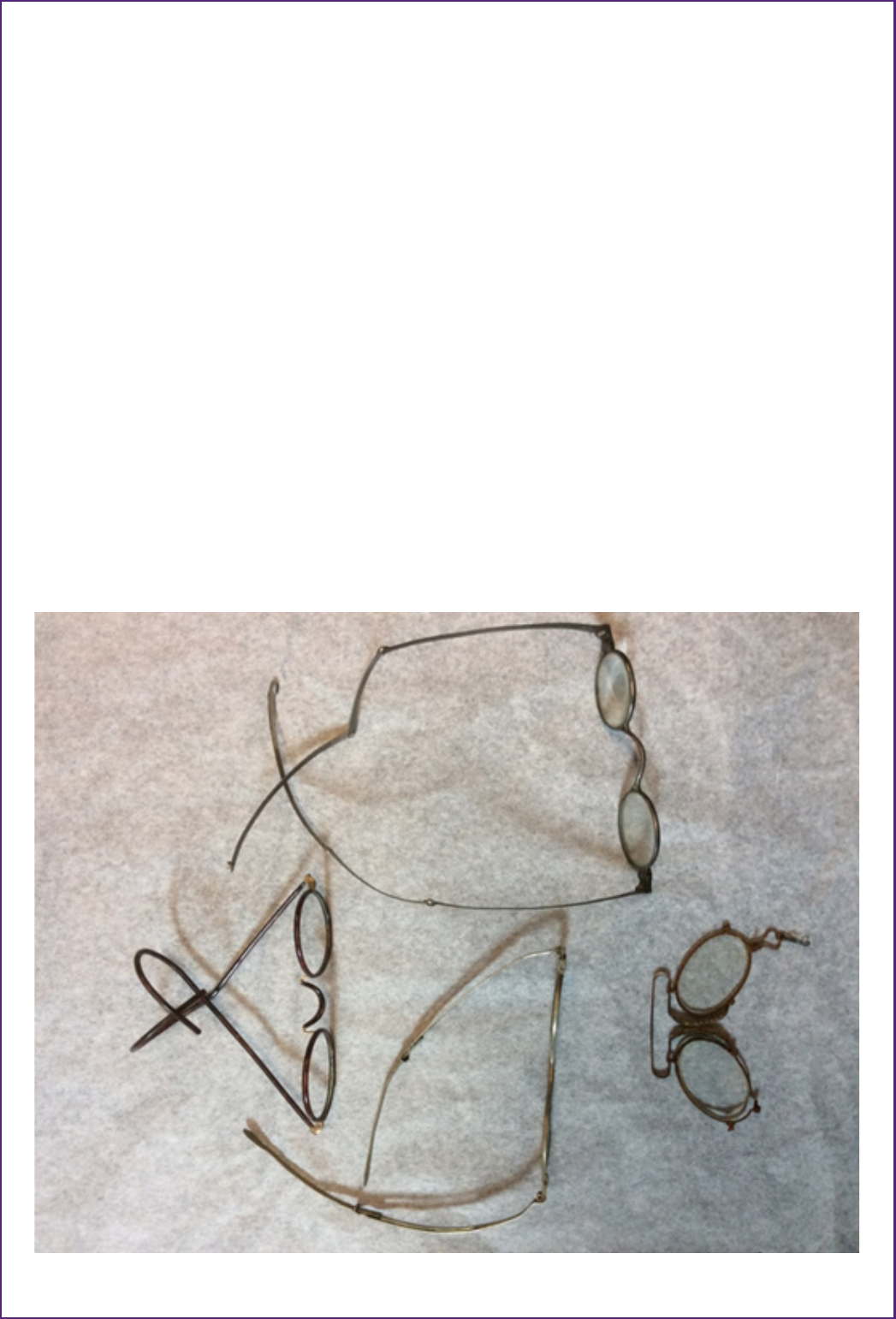

A selection of late 19th and earl 20th Century spectacles from the collection. (wikimedia.org: Conrad von Soest)

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 4

George Washington is credited for helping to

reduce the prejudice that glasses indicate frailty

by using them to read part of his speech to rally

his troops who were on the point of mutiny

in their encampment near New York in 1783.

This was widely reported, and they responded

with sympathy to his situation by withdrawing

their complaints. In London, in 1727, Edward

Scarlett made spectacles held comfortably in

place with arms passing over the ears which

slowly replaced monocles, pince-nez and

lorgnettes. These continue to be improved using

tough, light, alloys to make resilient frames

with emphasis on comfort, personal image and

fashion.

Further major developments came with the

Zeiss and Moritz Von Rohr spherical point-focus

lens in the early twentieth century. Plastics

replaced glass from the 1960s after acrylic

from the 1940s was found to be too brittle and

yellowed with age. Television heralded a huge

demand for distance vision correction in the

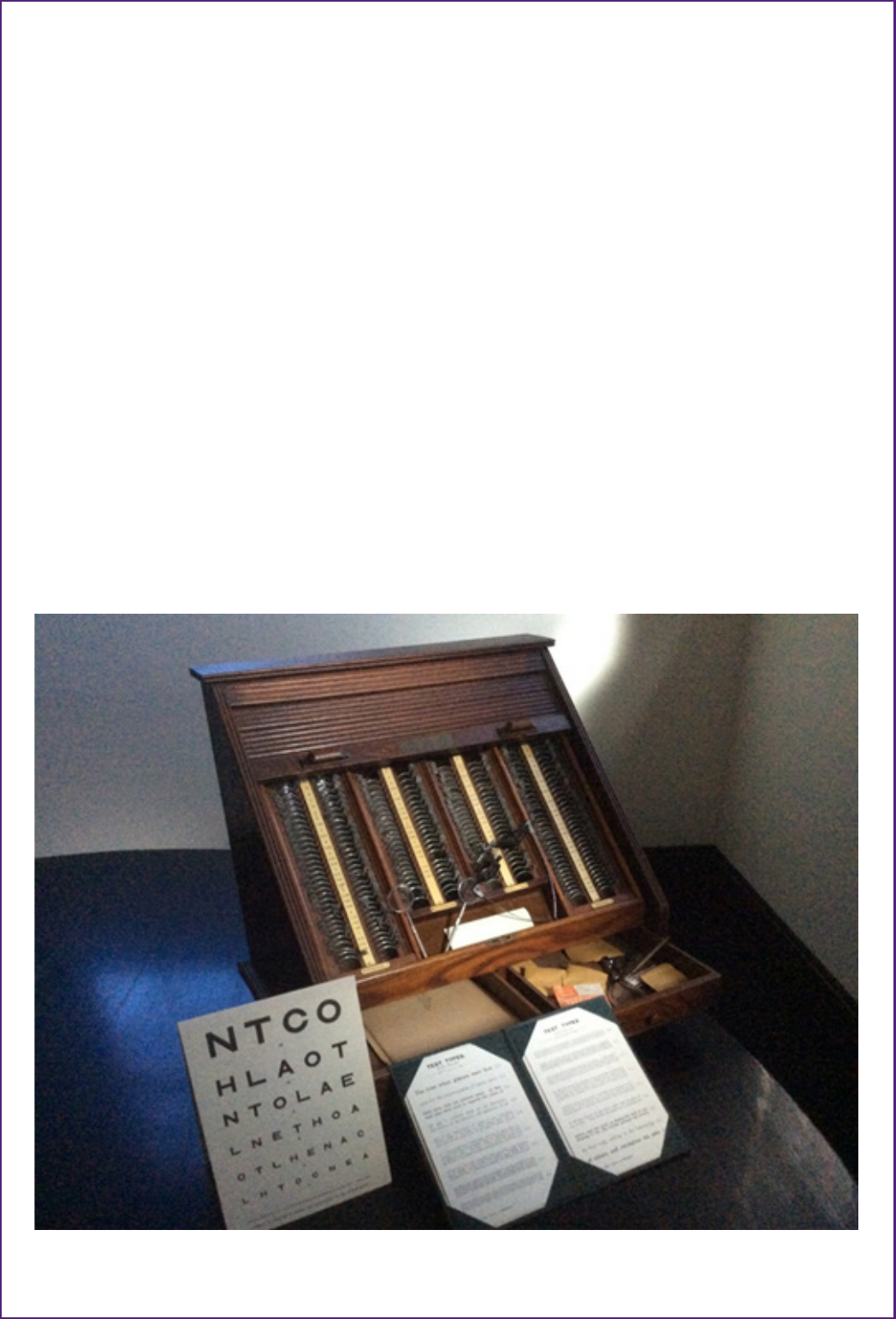

1950s. Testing of visual acuity and prescription

of glasses was carried out by a variety of

A Superior roll top testing kit for oce use in the collection. Used by Dr R Parker and Donated

by Dr Chester Wilson from Longreach

providers including doctors opticians and

pharmacists using a variety of lenses and other

aids such coloured dot charts to demonstrate

colour blindness and manually measuring

existing lenses.

The discovery of high refraction, durable plastics

together with glare reducing polarisation

encouraged thin, safe modern spectacles and

allowed light, fashionable frames. Contact

lenses and corrective surgery have made

inroads into the need for corrective vision

aids, but spectacles retain most of the market.

An adjustable corrective lens was produced

by Joshua Silver in 2008, using silicone and

a syringe to alter the lens curvature but this

has not been widely accepted. Like many

technological histories there is no clear

trajectory of the development of these everyday

items with a story full of numerous small

improvements and many contentious claims.

The development of licensing and training

of the providers of spectacles also seems to

be somewhat haphazard. The dispensers of

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 5

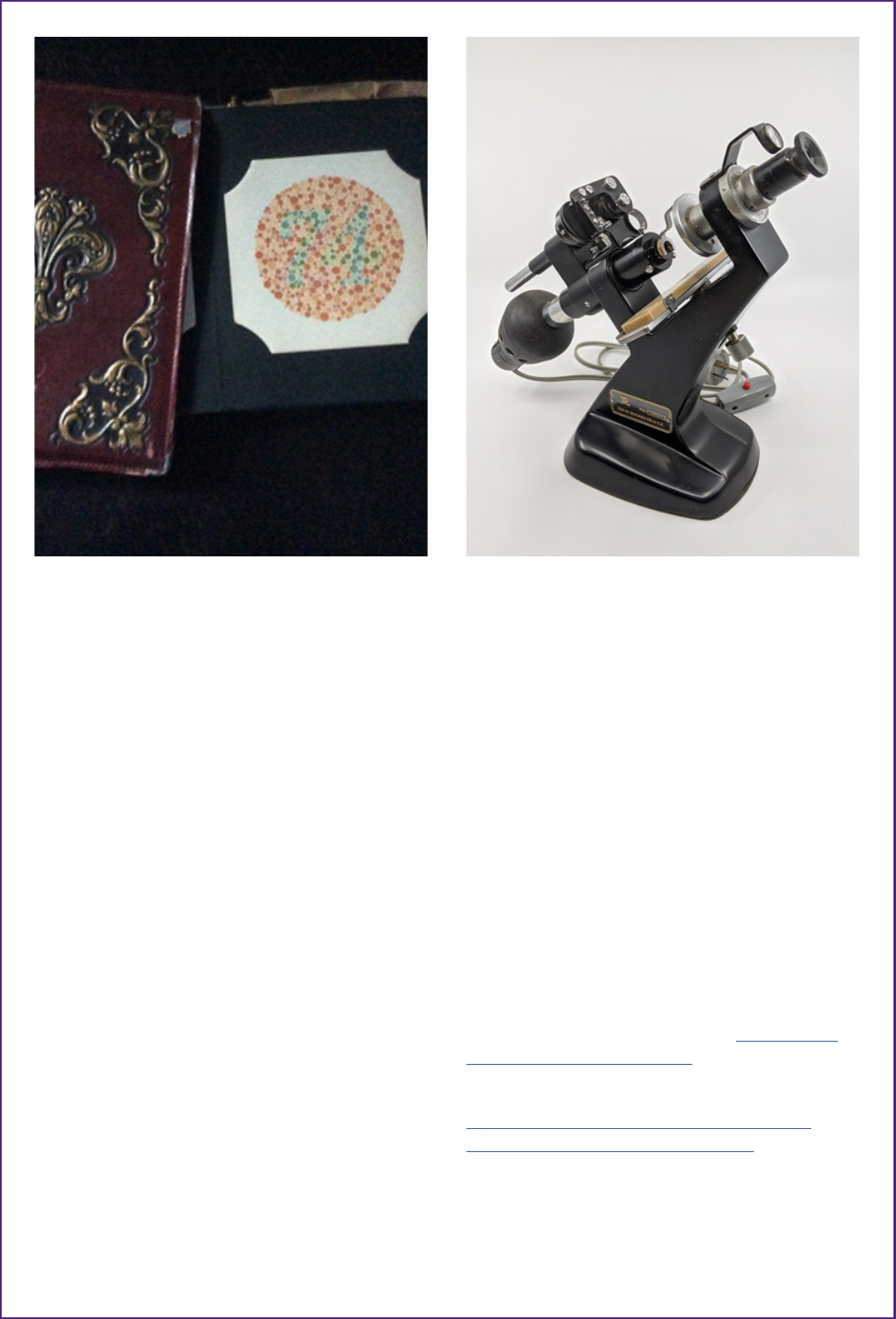

Ishihara published his colour blindness test in 1917 this

example with a tooled leather cover was published in

Tokyo in 1939

spectacles from an optical prescription are

called opticians and doctors were frequently

responsible for testing and prescribing lenses

and pharmacists sold them. Much of this

association was unregulated. Surgeons and

physicians specialising in eye treatments call

themselves ophthalmologists and often work

with opticians for refraction impairments

and before lens implants, after lens removal

for “ripe” cataracts, but their speciality was

primarily for the study, diagnosis and treatment

of diseases of the eye. However, many general

practitioners also continued to test eyes and

prescribe lenses and pharmacists still sell

reading glasses directly to their customers.

Optometry as a profession arose from non-

medical optical specialists and prescribers of

corrective lenses. Whilst existing for centuries

it was not until the latter half of the 20th

century that these professionals became

systematically regulated. They have slowly

separated from other health care providers but

in a few European countries such as France

and Italy and in some states in the USA, they

remain unregulated. In this country, they are

governed by the Optometry Board of Australia

and are self-regulating under the auspices of

A refractometer used byDGr R Parker in Longreach whilst

working as a GP with a special interest in Ophthalmology.

the Australian Health Practitioners Regulation

Agency. To celebrate the Australian College of

Optometry’s first 75 years, Professor Barry Cole

wrote “A History of Australian Optometry” in

2015. Orthoptists originally only treated eye

movement disorders but for many years their

university-based training has involved them

in other fields such as strabismus amblyopia,

diplopia and low vision disorders amenable to

therapy through eye exercises. It is noticeable

with training and organisation the professions

tend to extend their remit supporting the

tendency towards fragmenting health provision

into more compartmentalised and specialised

fields. (1408)

The most useful account I found was in the

History section (4.1) in Wikipedia (en.wikipedia.

org/wiki/Glasses#Precursors) which includes

appropriate references and links also:

optometryboard.gov.au/News/2015-07-21-

media-release-protected-titles.aspx

A History of Australian Optometry; Barry L.

Cole; The Australian College of Optometry, 2015

ISBN 978064937922

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 6

Tracheostomy and Tracheal Intubation

A Note by Robert Craig

Here are several examples from the collection of trache-

ostomy tubes with collars, introducers and loops which

allowed for attachment round the neck with a tape.

Tracheostomy has been commonplace for

more than a century. It was a precursor to

endotracheal intubation, the procedure which is

usually required for maintaining respiration for

ventilating unconscious or paralysed patients.

Tracheostomy was primarily used for bypassing

the airway obstruction due to oropharynx by

injury or most commonly by the hardened

exudate common in the tonsillar area due to

diphtheria. However, by reducing dead space

during inadequate respiration it was used to

improve ventilation in poliomyelitis and other

situations of chronic paralysis of the muscles of

respiration.

The museum collection has many examples

of tracheostomy tubes, usually made of silver

which, like gold, oered a modicum of self-

sterilisation. Some are in boxed sets and come

with the necessary instruments for performing

a tracheostomy. They all contain several small

sizes for use in infants.

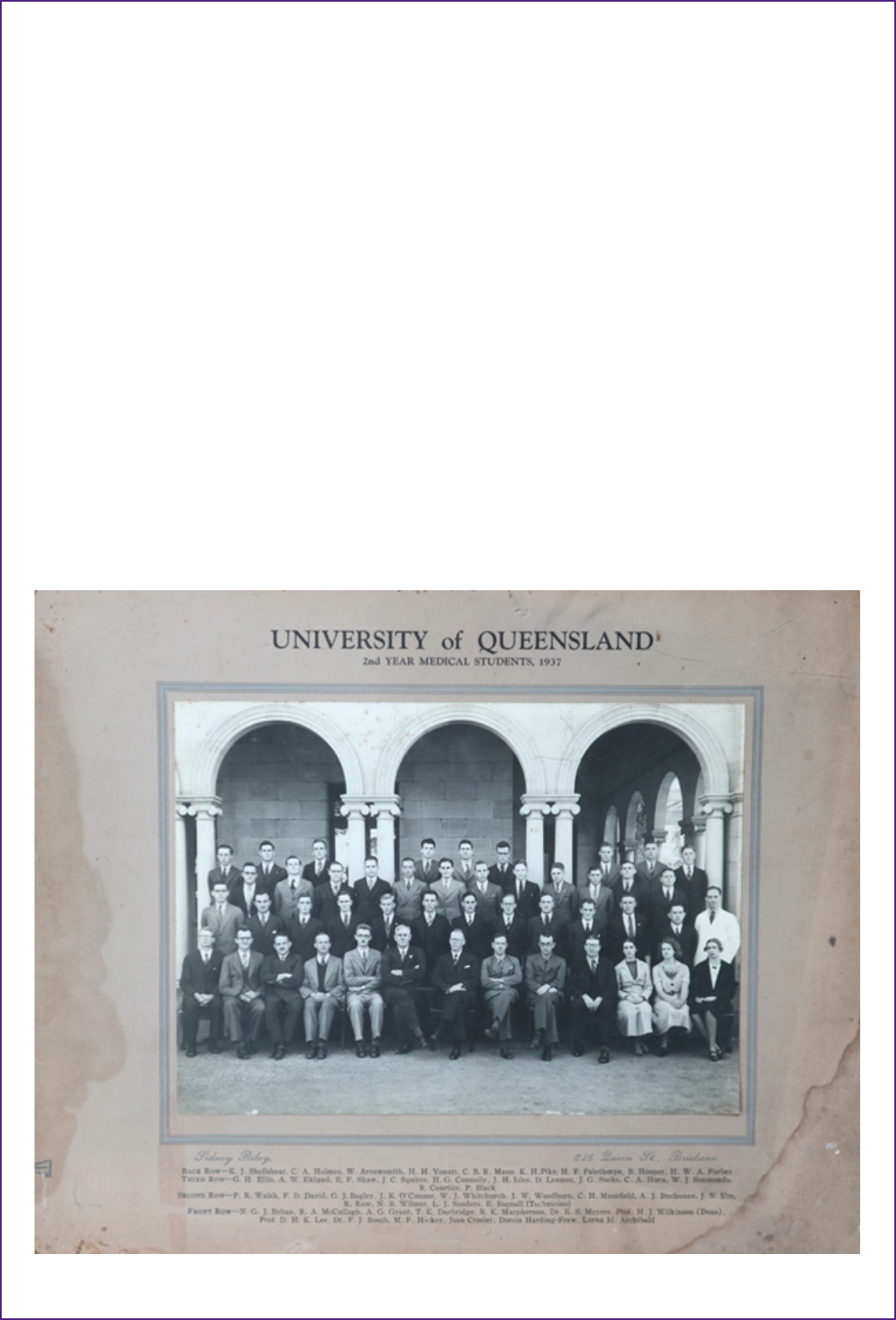

Taken from Hektoen International; An online

Journal of medical humanities www.hekint.org

Hetkoen International is a freely accessible

online journal which oers contributions on

the History of Medicine with a focus on aspects

from the arts and humanities. This illustration

comes from the August 2020 edition.

The intubation (le tubage). 1904. Georges Chicotot. Musee de l’Assistance Publique, Paris.

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 7

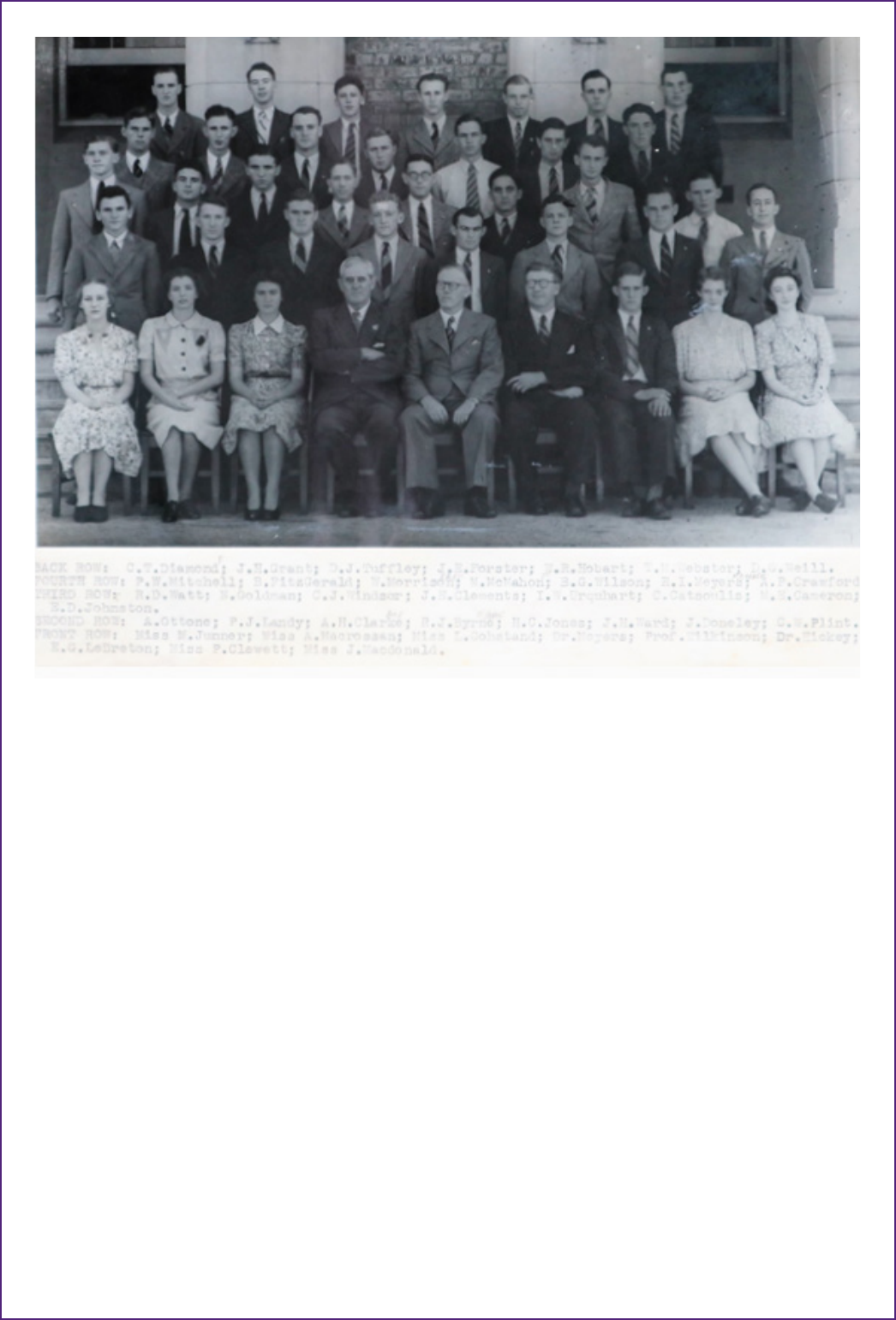

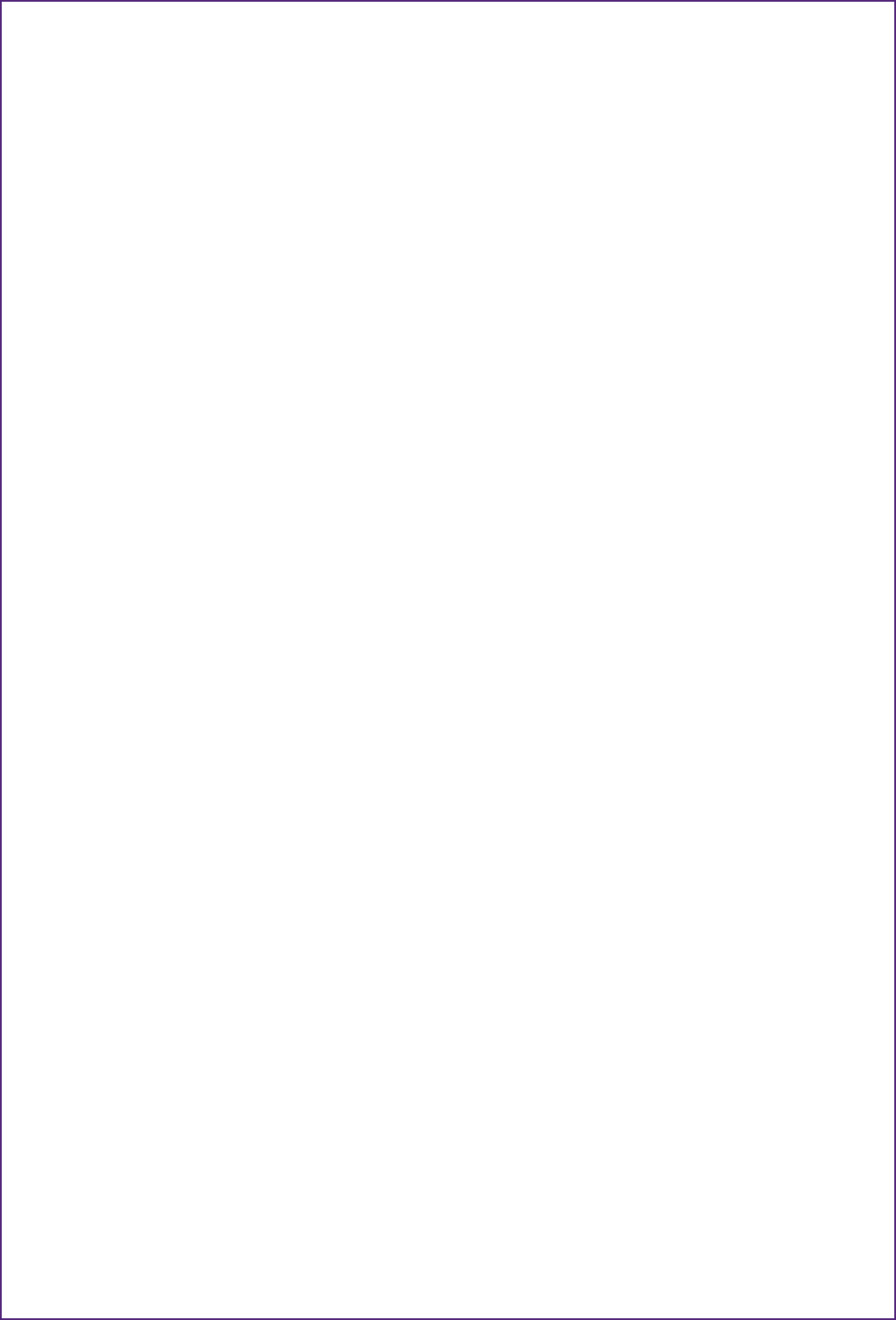

Jan Nixon, Volunteer, has worked for some years

on these photographs to catalogue and store

them satisfactorily. They provide an extensive

illustration of the Medical school from its

opening years to the present. The photograph’s

she has chosen to represent the collection

are the 1937 and 1942 second year classes.

Poignantly several of the names reappear on the

war memorial in front of the Mayne Building

Museum Photographs, The Marks-Hirschfeld

Museum of Medical History houses many

photographs. One interesting series in the

photographic collection is a group of large

black and white mounted photographs taken of

The University of Queensland medical students

when they were in Year II of their course. The

series dates from 1936-1958.

The location of the very early photographs is

Old Government House, George Street where

The MHMS Photograph Collection

Second Year 1937

medical students attended lectures. From

1938, photographs were taken in front of the

Mayne Medical School at Herston. The wartime

photographs taken for 1942 to 1944 show the

front doors of the building bricked in to prevent

percussive eects from the possibility of a bomb

exploding in the grounds. The bricks had been

removed by the time of the 1945 photograph.

There are studio identification marks on most

of these photographs. The initials ‘HJW’ appear

on the 1942 photograph. The 1946 photograph

was taken by Hal Stevens, 661 Sandgate Road,

Clayfield. Photographs for years 1937, 1939,

1940, 1943 and 1947 were taken by Sidney

Riley Studios, 246 Queens Street, Brisbane.

Interestingly, the 1947 photograph has a note

indicating: ‘Copies as Proof 6/- each (7/- with

names and heading) unmounted copies 5/- each

- students not identified on mounting’. Sidney

Riley Studios also photographed the second-

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 8

Second Year 1942

year groups from 1948 through to 1957 with

the possible exception of the copy of the 1953

photograph which is not mounted in a studio

folder.

The group photographs of second year medical

students and the later photographic sheets of

individual students in tutorial or year groupings

are often requested to display at year reunions.

Individual photographs are no longer taken due

to privacy issues.

Many students photographed during the Second

World War years joined wartime services.

The medical students who lost their lives in

such service are named on a memorial stone

at the foot of the steps of the Mayne Medical

School. The memorial also records the names

of those who have died in service including

Peacekeeping Missions since the Second

World War. Students from The University of

Queensland Medical Society (UQMS) hold an

ANZAC service at the site of the memorial each

year. Due to the COVID-19 virus, the service was

not able to be held in 2020.

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 9

MEDICAL STUDENTS WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES 1935-1945 AND IN MISSIONS SINCE THAT TIME

NAMES TAKEN FROM WAR MEMORIAL STONE AT FRONT OF MAYNE MEDICAL SCHOOL BUILDING.

AUSTIN, J. MED IV RAAF

DOUGLAS, H.B. MED II RAAF (1940 SECOND YEAR PHOTO)

GANNON, W.J. MED I AIF

HOOPER, B. GRAD AIF (1937 SECOND YEAR PHOTO)

KELLY, C.D. MED II RAAF

MACTAGGART, J. MED II RAAF

McGILL, J.A.D. MED II RAAF (1940 SECOND YEAR PHOTO)

MINCHIN-SMITH, G.G. MED I RAAF

RANDALL, N.P. MED I RAAF

RYDER, J.S. MED III RA VR (1940 SECOND YEAR PHOTO)

STAPLES, H.B. MED I AIF

1952 PURSSEY, I.G.S. MED II RAAF

1993 FELSCHE, SUSAN MBBS RAAN MC-UN (STUDENT PHOTO WAS SHOWN IN MUSEUM WOMEN

AT WAR EXHIBITION)

1997 PAUL McCARTHY MBBS RAAF

Other historic group photographs held by the Museum include:

Inauguration of Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, October 1936.

Teaching sta and first class. Photographer not named. Black and white photograph.

Graduates of Medicine 1952 with names listed, Regent Studios, 43 Queens Street, Brisbane. Black and

white photograph.

The First Convention of Medical Students of Australia, May 1960. Courtesy of the Fryer Library, The

University of Queensland. Black and white photograph.

Resident Medical Ocers 1962 in a folder with names. ‘Casey’s Cameras’ is embossed on the folder.

Black and white photograph.

Graduation Dinner 1968 with names listed. David McCarthy and Assoc. Black and white photograph.

One copy framed and one copy laminated.

Surgical Professorial Unit, General Hospital, March 1975. Photographer not named. Black and white

photograph.

Full-time Academic Sta and Alumni, Department of Child Health for the 75th Anniversary of The

University of Queensland, 1985. Graham Jurott, (photograph in colour).

Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland Golden Jubilee 1986 with names listed. Graham

Jurott, (Photograph in colour).

Sta of the Faculty 1991. Photographer not named. Black and white photograph.

1990/1991 and 1995 graduation photographs in colour (photographer/s not named)..

Many photographs of celebrations and events such as anniversaries and book launches were taken

by Mr. Graham Jurott who was Senior Photographer at the Faculty of Medicine, 1964-1993. He also

photographed a beautiful black and white series of the artistic details on the Medical School building.

We sadly marked Graham’s passing in October 2017.

Mark Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History - newsletter April 2021 - 10

Would you like to share your experiences with medicine?

We invite readers to share their personal memories and experiences of studying and practicing med-

icine or other health disciplines in Queensland. These stories will form a new, regular column of the

Mark-Hirschfeld Museum newsletter. Please email your story to [email protected].

Donate to the Museum

The Museum is managed by a team of dedicated volunteers. Our generous philanthropic supporters

are vital to the works of the Museum, and we welcome donations in support of our collection preser-

vation and archival programs, exhibitions and educational activities.

Through your gift you will be playing a vital role in preserving medical history and building a signifi-

cant collection to deliver inspiring and engaging learning opportunities to our students, researchers

and the community.

You can support the Museum by donating online, contacting us on 07 3365 5081 or emailing

med.advanc[email protected]

Become a volunteer

If you’d like to join the volunteer team, please contact us at medmuseum@uq.edu.au

Contribute to the Museum newsletter

The Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History newsletter is issued four times per year. We are

always on the lookout for interesting materials that explore the rich tapestry of medical history. If you

would like to contribute a story or have a topic that you would like to see included in future editions,

please send an email to [email protected].

Our next newsletter will be distributed in July

2020. If you are interested in submitting an arti-cle,

please send your story and photographs by no later than Monday 21 June.

Share your feedback

What do you think of our new newsletter format? Do you have ideas for new sections or subjects?

Send through your thoughts or suggestions by clicking here.

The University of Queensland, Level 6, Oral Health Centre, Herston Rd, Herston Qld 4006

www.medicine.uq.edu.au

CRICOS Provider Number: 00025B to [email protected]